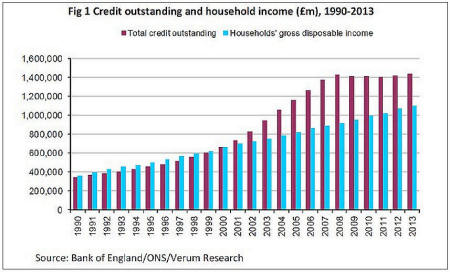

Indebtedness expanded explosively prior to 2008, and made a

severe crash inevitable. The underlying cause was massive risk-taking on the

part of the finance sector, but it was helped by complacency on the part of

governments and regulators. This complacency seems quite extraordinary, given

the exponential rise in household debt in the years preceding the 2008 crash -

see figure 54.5. It was helped by the theories and economic models used by

central banks, the treasury and other policy-making agencies - the so-called

Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models. The name sounds

impressive but the underlying assumptions are less so. Those theories and

models assume that as long as inflation stays low then financial and

macroeconomic stability follow. They therefore ignore much of the financial

system - banks are almost entirely missing and there are no mortgage lenders or

financial traders (Turner 2016 p170 and Desai 2015 p197), so it is no wonder

that household debt can't ever be a problem. That policy-making bodies can

apply methods that are so far out of touch with reality is quite staggering. Not

only that, they are still being applied even after the crash. As Turner observed:

You cannot see a crisis coming if you have theories and

models that assume that the crisis is impossible. (Turner 2016 p246)

DSGE models are considered further in chapter 80.

Debts exploded when banks persuaded regulators to relax the

rules on securitisation - the selling of derivatives based on debts, especially

mortgages, to investors. These were touched on earlier in chapter 50. This was

the key element that removed the need for caution in the selection of debtors

by creditors. Increasing creditor profit depends on increasing debts, which

depends in turn on finding a steady supply of new debtors to take on the debts.

With traditional caution this requires high quality debtors, the supply of

which dries up fairly soon, as does the growth in creditor profits. But without

caution the supply is almost endless, and culminated in the ludicrous situation

where money was lent to debtors with no creditworthiness at all - no income,

no job, and no assets - the 'NINJA' borrowers. These were the 'liar loans', given to people

against properties that they couldn't hope to pay for but would cover the

investors' and banks' loan and associated interest and fees when repossessed. How

anyone, especially regulators, could have seriously thought that this was an

economically harmless activity is amazing. It was all based on the belief that

property prices would keep on rising. Why should we care if a borrower can't

make the payments? We just repossess their property and sell it to pay off the

debt, with a few nice fat fees for our trouble. What about the people who are

made homeless? Who cares about them? We're making money and that's all that

matters.

To see how these debts worked we need to examine the three

main parties involved: the investors who wanted to own them (the creditors);

those who made them available to investors (the finance sector); and the

borrowers who funded everything (the debtors).

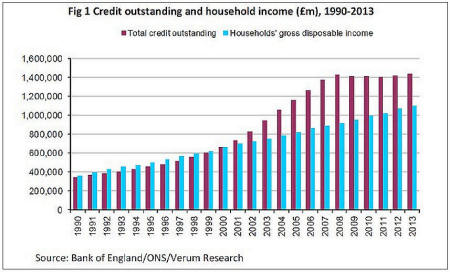

These were mainly the growing number of people, institutions,

businesses and governments with sufficient excess of money over and above their

requirements to wish to invest it, preferably for a high and secure return. As

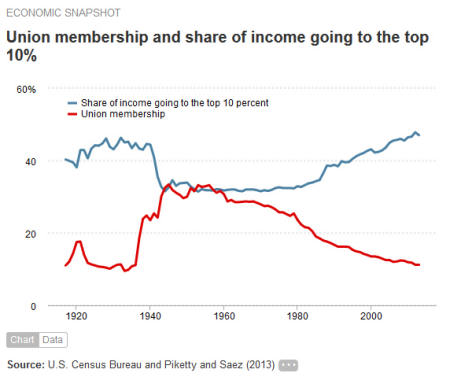

the chart below shows, from 1980 onwards, when the Thatcher and Reagan Governments

began the process of removing power from unions and the workforce in favour of

employers and cut the rate of tax for high earners, wealth inequality began to

climb. Figure 54.1 shows the growth in US income for the most highly paid from

that time onwards related to the decline in trades union membership. The UK

situation was similar.

Figure 54.1: Relationship between the decline in workforce

power and wealth for the top 10%. Source data from The US Census Bureau, Thomas

Piketty and Emmanuel Saez,

recovered from http://www.epi.org/publication/unions-decline-and-the-rise-of-the-top-10-percents-share-of-income/

Much of the increased income for high earners and for their

businesses became available for investment, and as a result the demand for

financial assets began to increase with corresponding price increases. The

effect of a price increase for an asset that delivers a fairly constant return

in terms of income (as do bonds and equities) is to make the ratio of price to income

higher. This is reflected in lower interest payments for debts, and in a higher

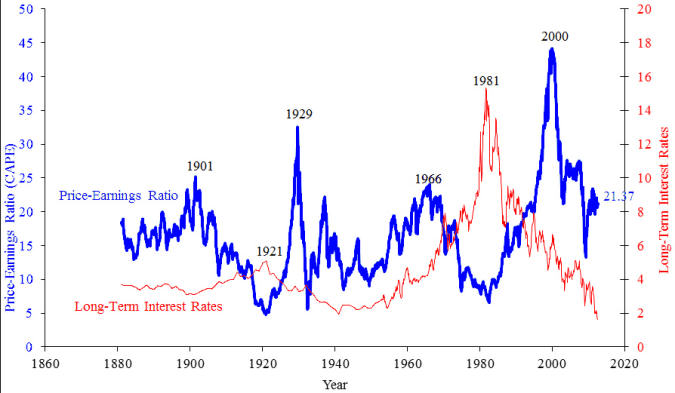

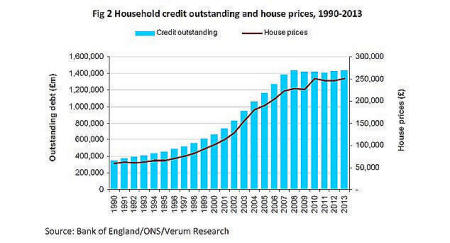

price/earnings ratio for equities. The effect is seen in figure 54.2.

Figure 54.2: Long-term interest rate and price/earnings

ratio. Modelled on a plot from the book 'Irrational Exuberance' by Robert

Schiller, 2005, with data taken from http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls.

Recovered from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Price%E2%80%93earnings_ratio

It shows that the long-term interest rate was in steep

decline from 1981 onwards, so the returns on traditional debt assets such as

government and corporate bonds grew correspondingly lower. Returns on equities

were also in sharp decline, at least until 2000 when the dotcom bubble burst,

the chart showing the price to earnings ratio increasing rapidly in this period.

After the dotcom crash equity returns improved as their prices dropped, but the

appetite for them remained constrained because so many had lost money in that

crash. Therefore those with money to invest had an increasing amount of it, and

that provided a strong demand for investments, the more secure the better, and

bond prices rose correspondingly.

From the mid-1980s, when the finance sector expanded

massively in the wake of 'big bang' deregulation, the

opportunities for banking and financial innovation increased dramatically and

the bankers and financiers were not slow in taking advantage of them. Remember

that banks' profits depend on the amount of money they create, so the more they

create the better it is for them. But there is a problem - banks are

constrained by the need to keep risks to an acceptable level. Remember from the

last chapter that there are plenty of potential borrowers, and the less able

they are to repay the more there are, so a bank finds itself in severe

competition with other banks for high quality borrowers that all banks want to

attract, but must turn away low quality borrowers that no bank wants to attract.

If only there was a way to get rid of the risky loan agreements it could take

on more of the risky borrowers.

Bright idea no 1! Sell the loan agreements to others.

The advantage for the banks is that they sell the risk along with the loan

agreement and no longer need worry about creditworthiness, but the disadvantage

is that the investor gets the interest payments instead of the bank. That won't

matter though provided that the bank gets a nice fat fee, and uses the money

(or more accurately the reserves that accompany it) from the investor to fund

another loan agreement, and keeps on doing that indefinitely. That way the

gains will massively outweigh the losses - perfect! But investors aren't

daft, they know that the loans are risky, so no-one would buy a loan as it

stands except at a very deep discount. Besides that banks don't want to have to

find buyers for every separate loan that they have on their books, they want a

rapid and continuous transfer of loans to investors.

Bright idea no. 2! Package up the loans so as to average

out all the individual default risks, then slice them up and sell the slices. That

still sounds a bit dodgy so let's call it 'securitisation' - that sounds much

more respectable.

But why would anyone buy a slice? Investors would know that some proportion

would go bad so the quality of the investment would be hard to determine and

they would most likely play safe and not touch it.

Bright idea no. 3! The bank itself could specify the

risk by first carving up the mass into a small number of big slices, and

arranging them in a tiered hierarchy such that any defaulting loans would

affect the lowest tier first, then if there were even more defaulting loans the

next tier would be affected, and so on, each tier carrying a different interest

rate - highest at the bottom because that tier carried the highest risk and

lowest at the top because that tier carried the lowest risk. These tiers were

called tranches, each appealing to a different type of investor related to risk

appetite. For example cautious pension funds would only buy from the topmost

tranches whereas hedge funds would buy from all tranches. The rating agencies

would be called in to rate each separate tranche to give confidence to the

investors, and nice fat fees paid by the banks to the agencies for their

trouble together with the promise of a continuing supply of products to rate

would keep them well disposed to the bank and its products. The group of loans

packaged up would be called Mortgage Backed Securities (MBSs) if made up of

mortgages of varying quality, also called Collateralised Mortgage Obligations

(CMOs), or Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) if made up of different types

of loan - mortgages, car loans, student loans, credit card loans etc. The

collective name for these is asset backed securities (ABSs). In each

case the investor would have the original assets in the package as collateral

in the event of the provider going bust. Looking good!

But here the banks ran into another problem - the risk

limits imposed by regulators. Note that the investors didn't buy any of the

original loan agreements, those agreements stayed with the bank. The investors

bought a contract, typically giving them the right to a rate of interest for a

specific duration, after which the original cost of the contract would be

repaid by the bank - just like any other loan agreement. The investors didn't

in fact buy a slice of a package of loan agreements; they bought a slice of an

income stream that was funded by a package of loan agreements. This is

important because only the bank knew what was in the package of agreements, all

the investors knew were the terms of the contract they had with the bank, the

rating of it by the rating agency, and the fact that what they had bought was

collateralised by loan agreements, but exactly what that collateral consisted

of was unknown to them. In fact it was much worse even than that because for

simplicity we have been considering the bank as the sole player in making the

original debts available to investors. In fact there were dozens of players,

all playing some part in the complex web of dealings, so neither the banks nor

anyone else knew for certain what the packages contained. Unbelievable I know

but true nonetheless! It was that ignorance that brought the world to within a

whisker of economic collapse in 2008.

To see why risk imposed a limit we have to consider a bank's

balance sheet. The money paid by the investor would largely appear as reserves thereby

adding to the bank's capital, but those reserves would disappear again when

another loan agreement was accepted and the borrower spent the money on a

house, car or whatever, and the seller banked with a different bank. Over time

the bank's balance sheet would show a growing number of loan agreements (risky

assets) and a growing number of ABS liabilities, with the bank's risk-free capital

base unable to keep pace. Therefore the ratio of risk-free assets to risky assets

would keep dropping until the regulator stepped in to stop further growth.

Bright idea no. 4! Sell the risky loan agreements to

a separate company, wholly owned by the bank but operating under a trust

arrangement so that it could carry out business independently of the bank. These

trusts were known as Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), and were not banks, so

they could attract much higher levels of debt than could a bank as they weren't

subject to any risk limitation. The SPV would initially borrow money, normally

from the money market (because borrowing from banks would just load the banks

back up with risky loan agreements) to buy the first batch of loan agreements,

but would buy later batches using money from the investors who bought the ABSs.

The effect for the bank was that the loan agreements (long-term risky assets)

were removed from its balance sheet and replaced with money in the form of

reserves (short-term safe assets) from the SPVs, which it could use to fund more

loans. There was no limit to this process because the bank's risk limitation

was no longer challenged. The effect for the SPV was a build-up of both

long-term risky assets (loan agreements) and liabilities (ABSs), but this

build-up wasn't a problem because it had no risk limitation to worry about. The

SPV would normally work with other companies that did all the slicing, dicing

and making the ABSs available to investors, and were located in tax-friendly

environments so as to avoid paying what they owed to the country in which the loans

were taken out.

Sorted!

As a further twist to the tale some investors wanted

insurance against defaults, so a new derivative was invented for the purpose -

the Credit Default Swap (CDS). In return for fees paid by the swap buyer to the

swap seller for the duration of the contract, the seller would agree to make

good all interest payments and the final capital repayment in the event of a

default on the original debt contract. In effect the CDS buyer swapped the

credit default risk that came with the ABS contract for a risk free contract

with the CDS seller - the CDS seller taking over the risk in return for the fee

that was paid. These were extremely popular and very lucrative for the sellers,

notably American International Group (AIG), which collected fees without any

thought that they might have to pay out. So confident were they that they were

happy to issue CDSs to anyone who wanted them, regardless of whether or not

they owned any ABSs. In other words in the event of a default on a debt

contract the issuer would be required to pay many times over the value of the

default. This was because such derivatives were classed as swaps, not

insurance, which in reality they were. Anyone wanting insurance is required to

own or at least have a material interest in the asset insured, if the insurance

is classed as a swap then they don't. I have house insurance which gives me

peace of mind, but I would have a good deal less peace of mind if I discovered

that dozens of other people I didn’t even know had also insured my house!

Anyone interested in this story is recommended to read 'The Greatest Trade

Ever' by Gregory Zuckerman (Zuckerman 2010), which tells the story of the

trader John Paulson who predicted the economic crash and made the biggest windfall

in history, by betting against the market using CDSs.

Yet another complicating factor was that many non-bank

finance companies also offered mortgages and other loans, and funded them

initially by borrowing from the money market rather than by creating bank money.

In that way they avoided falling foul of the client money rules (see chapter 47)

- they didn't take deposits - so weren't regulated as banks and could therefore

take bigger risks by operating with much less capital. Later, as they packaged,

sliced and sold rights to the income stream from loans money would come in from

investors so less would need to be borrowed from the money market. These

companies offered credit to the borrowers but didn't create money because they

lent existing money. However by means of the packaging and slicing process they

created what is known as 'near money' - assets (i.e. ABSs) that are (or were at

the time) easily exchanged for money in the market. In that respect they

operated very much like traditional banks, not only offering long-term loans to

borrowers but converting them into short-term liquid assets to sell to

investors. This is another form of maturity transformation process that was

discussed in chapter 40, but this time the liquid assets were near money rather

than money itself.

The term 'near money' is interesting. It is considered by

many that because financial institutions can easily create near monies in

effect they create money, so there is no point trying to control banks'

creation of money because others would just step in to create near monies which

would defeat the object. In reality, as the 2008 crash so clearly showed, near

money only deserves its name when everyone, buyers and sellers, believe in its

worth. When there is doubt, as there was with ABSs in 2008, they become

anything but near money! No-one would touch them at any price. There is no way

that a non-bank can create money or genuinely near money that retains its value

under all circumstances, because the only thing that holds its value in terms

of money is money. I like the Positive Money definition of money - it is that

which passes the 'Tesco Test' - if you can walk into Tesco's with it and buy a

basket of groceries then it's money, if you can't then it isn't. So called near

money is no reason to give up on the ambition to control banks' money creation

activities as discussed in the next chapter.

The above explanation is a very brief summary of the essence

of what the banks and finance companies were up to. In practice it was

immensely complex, with very many separate players involved (though several of

them often owned by the same entity). The whole structure apart from the

traditional banks became known as shadow banking because of the many

players that weren't banks but in effect did business that was traditionally

the preserve of banks. As an indication of just how complex the arrangements

were, after the 2008 crash the Federal Reserve Bank of New York wrote a paper

which is available online

and contains a map of the shadow banking system on a single sheet of A4, but in

order to read the labels clearly this must be magnified 6 times to form a

legible map of about 5 feet x 3 feet! I think it is fair to say that no-one

understood or indeed understands the full complexity of all this. Individual

players understood their own part in it and those they dealt closely with, but

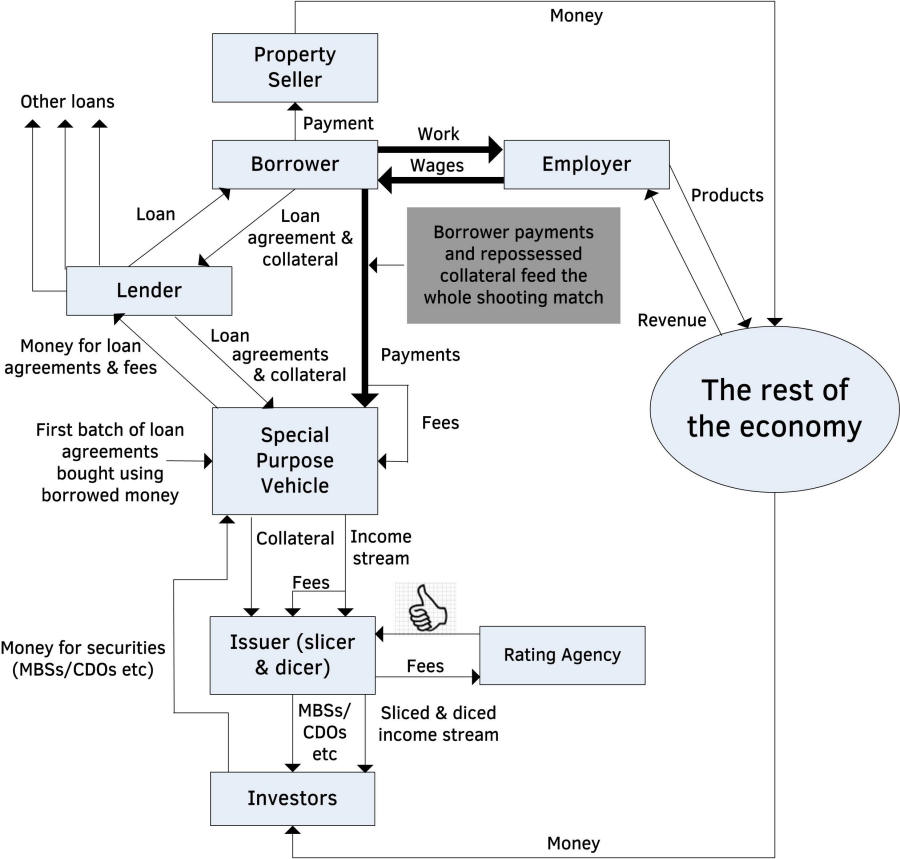

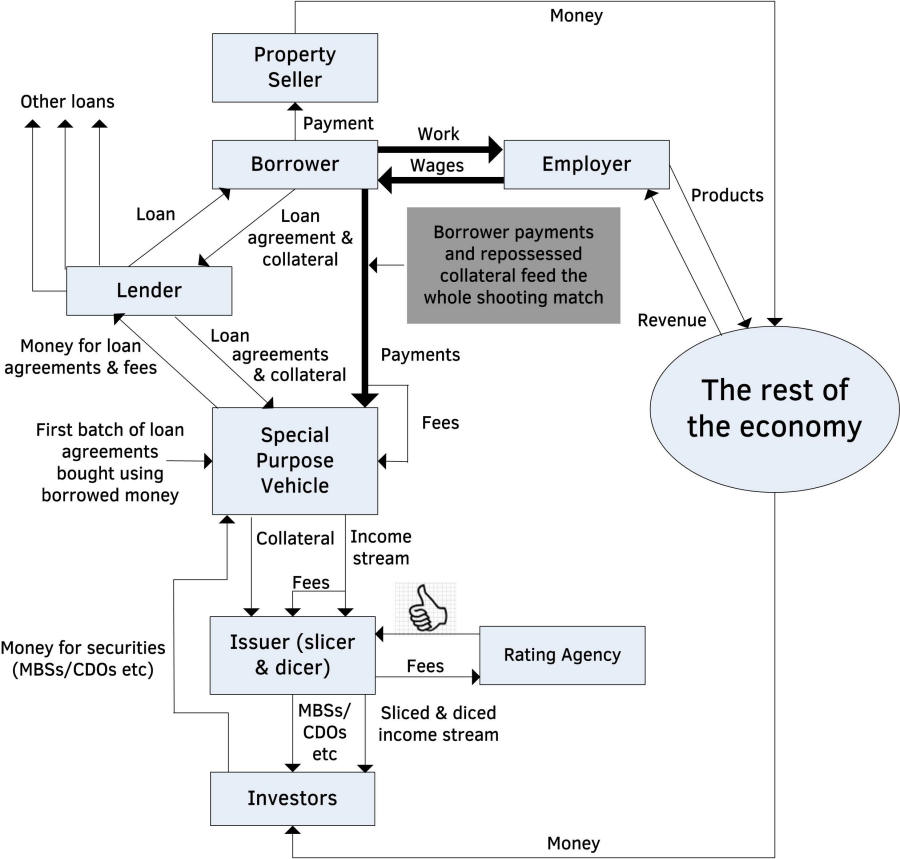

no individual needed to understand all of it, except in conceptual form. Figure

54.3 below gives an outline of the structure.

Although no-one understood it all the many players were very

well rewarded for their efforts, and the final investors also enjoyed a

handsome return, all funded by the borrowers at the bottom of the pile, and

they are considered next.

Figure 54.3: An outline structure of the securitisation

process.

In order for the whole house of cards to stand up there has

to be an increasing number of borrowers at the bottom, not only taking out new

loans but also hopefully paying them back. If new borrowers can't be found then

banks won't have anything new to package up and investors won't be able to

continue investing in these products. The wonderful money-making machine would

grind to a halt.

How can banks and investors be sure of a continuing supply

of borrowers? Well here's the really clever part - clever that is in a deeply

sinister sense - the more money that is in wealthy hands the more that ordinary

people have to borrow it back in order to live a normal life. It is fuelled by

the 'hoover-up' phenomenon - it's what neoliberals prefer to call

'trickle-down' - which we met in chapter 20, but here it became

supercharged. This is how it works. Banks create new money and make it

available to borrowers in return for loan agreements. These borrowers aren't

investors so they spend the money mainly on new wealth - houses, cars,

furniture, holidays, consumption goods, university education and many other

things, but mainly houses. That expenditure helps the economy because it

provides income for wealth producers. Even if the new money is spent on

existing houses it eventually finds its way back into the economy when people

at the top of housing chains downsize and spend the excess or they die and their

offspring sell the property and spend their inheritance - though there can be a

long delay as discussed in chapter 23 during which time house prices rise. The

borrowers, in paying interest on the money borrowed, provide the income stream

that provides all the fees to the banks and shadow banks, each taking their

cut, with the residue going to the investors who buy the ABSs. In order to

provide the income stream the borrowers must work in the economy, using a

portion of their earnings for the purpose. Now that income stream in the hands

of banks and investors represents money available for yet more loan agreements.

At this point banks and borrowers together have injected new money into the

economy which fosters growth, but also set up a process whereby a continuing

flow of money runs from the debtors back to the banks and investors. With this

process the banks are a lot less concerned about the creditworthiness of the

borrowers because the default risk is transferred to the investors, so the new

generation of borrowers consists of people who would have struggled to obtain

loans in earlier times, but now see an opportunity to improve their lives using

borrowed money - these are the people who represent the continuing supply of

borrowers. The main purchase that borrowers make is houses, so with more

willing buyers property prices rise, generating even bigger loans and also a

'feel-good' factor amongst home owners, and because home owners are voters the

government feels good too. Existing property owners also join the party by re-mortgaging

in order to spend their newfound 'wealth', except that their wealth hasn't

changed at all, their house is still what it was before the price rise. All

that has changed is other people's willingness to buy it, and willingness can

disappear as fast as and usually much faster than it appeared. As investors

notice that property prices are rising they see it as a good investment in its

own right, so they also rush to buy property, assisted by banks offering

'buy-to-let' mortgages. People unable to buy their own property have to rent,

which represents interest on the borrowed property, and as prices rise rents

also rise. Note that property hasn't become more intrinsically valuable in

terms of use value, its exchange value has risen purely because there are more

willing buyers than willing sellers, all convinced that prices will rise yet

further - the classic recipe for a bubble. As property prices rise in excess of

inflation mortgage payments and rents take an even bigger slice of people's

income and it all largely goes to banks and investors - this of course is no

more than business as usual - take from the poor to give to the rich - but in

the run-up to 2008 it was on steroids.

Although money used to buy ABSs was existing asset money

(MEA), the BoE reserves that accompanied it were used by the banks to fund the

creation of new money mainly for property purchase, so much of this new money

became new wealth money (MNW) when it was spent in the economy by the new house

builders and existing house sellers. That was why there was economic growth in

this period - whenever money is taken from the stock of MEA to increase MNW

then growth is fostered provided that there is spare capacity to absorb it -

see chapters 23 and 24.

Note that although bank money is created when a loan is

made, it is destroyed again when investors buy ABSs - recall the general rule

that a bank creates money when it pays out in bank money and destroys money

when it receives payment in bank money, see chapter 44. ABSs represent debts

sold by banks (or Special Purpose Vehicles on banks' behalf). Therefore although

the total value of debts was increasing the total value of money was not

increasing at the same rate, so the danger of rampant inflation was much less,

and indeed didn't happen apart from in property and asset prices. Other

institutions than banks also offered mortgages and sold ABSs - shadow banks -

but in their case no money was created or destroyed, so again the overall money

supply wasn't affected although debts still mounted.

Banks were significant buyers of ABSs because they were

rated highly and therefore didn't harm the risk ratio as much as the underlying

loan agreements would have done, so when doubts arose as to their real value

those doubts also fell on the value and solvency of banks. It was those ABSs -

toxic assets - that eventually crashed the system.

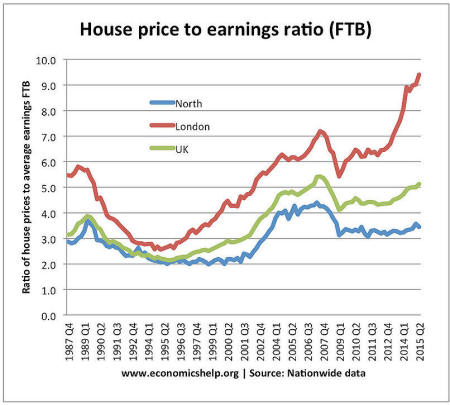

Because people need somewhere to live they must either

borrow the property and pay rent on it, or borrow the money to buy it, as

indeed they always have done. But with the advent of easier credit for less

creditworthy borrowers and easily available buy-to-let mortgages - making

property a much more popular investment - demand for it increased and prices

rose considerably in consequence. Rising prices mean bigger mortgages and higher

rents, and a higher proportion of people's wages used to pay for them, money

that flows back to banks and investors. This money is then available for

further investment in mortgages and property and so up go property prices

again, and up go the mortgage payments and rents and so on in an ever-increasing

spiral. The driver at the bottom is people's need for somewhere to live and the

effect is an accelerating accumulation of debt and therefore an ever-increasing

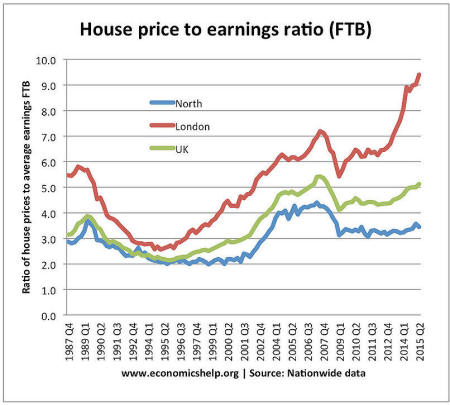

proportion of their earnings taken by banks and investors. Figure 54.4 shows

this as the house price to earnings ratio for first-time buyers (FTBs).

Figure 54.4: House price to first-time buyer earnings

ratios for London, the North and UK as a whole. Source Economics Help website

by Tejvan Pettinger, retrieved from http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/5709/housing/market/

The relentless rise from 1994 to 2007 is clearly seen, amplified

as ever for London property, and after the dip which lasted until 2009 it has remained

fairly static for the north but taken off again and climbed even higher than

before the crash for London.

People are forced to borrow either money or property from those

who own it, and pay them handsomely and in increasing amounts for the privilege.

With so much money circulating around the economy the rate of interest was low

during this period - see Figure 54.2 - so the amount of debt was able to rise

to unprecedented levels - people's ability to repay depends on the level of

interest payments rather than the level of debt, so with low interest debt can

be very high.

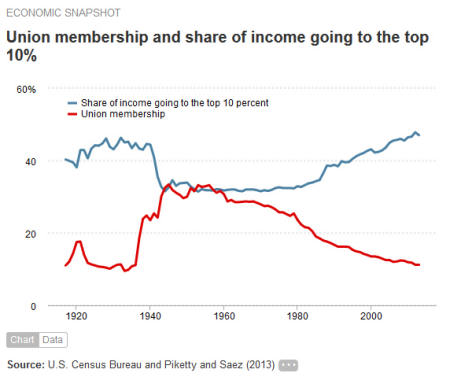

Figure 54.5 below shows the accelerating trend in household

debts and the increasing gap between debt and income until it was stopped by

the crash of 2008. Income is now catching up slowly but the level of debt

remains very high. Note though that the income in the chart is an average so it

includes the income of the wealthy, therefore non-wealthy income isn't rising

at anything like the same rate.

Figure 54.5: Household debt (credit) outstrips household

income. Retrieved from http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-2724894/Families-red-pose-threat-UK-recovery-household-debt-quadruples-1990.html

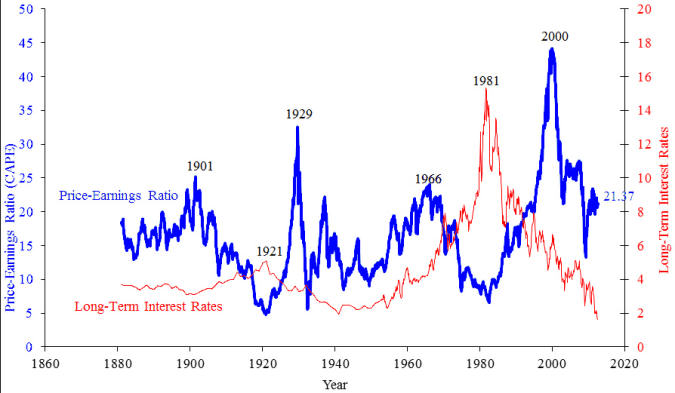

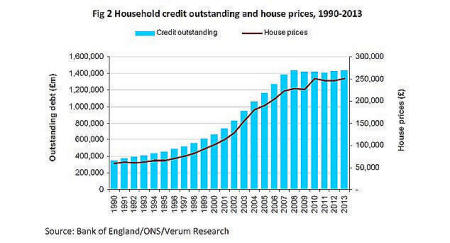

Figure 54.6 shows house prices keeping pace with the growth

in household debt up to 2008, indicating that the bulk of loans were to buy

property.

Note that these charts don't include borrowed property as

debt, although that's what it is because interest in the form of rent is

payable on it, so in reality the aggregate household debt burden is and was

considerably higher than indicated.

Figure 54.6: Household debt (credit) and house prices

remain closely linked. Retrieved