Of all the injustices and abuses of the current financial

and economic systems the most harrowing by far are those suffered by the

populations of poor countries. Here the freedom conflict discussed in the Introduction

is at its most extreme, because international control is weak, so freedom is at

its maximum for the unscrupulous and at its minimum for poor populations. In

international dealings wealth power goes well beyond unfairness and

exploitation, it costs lives, especially children's and infants' lives, in

their millions, year after year. It is made worse because everyone involved is

forced to compete using the rules set by the most unscrupulous, because

otherwise the businesses and associated investments of the less unscrupulous

fail. It's the same old excuse - if I don't operate this way then someone else

will - and although it's a poor justification it's true, and shows that control

must be applied at a higher level, because players aren't able to exercise

effective control themselves.

This is the arena that demonstrates more brutally

than any other just how much more important the acquisition of wealth and money

is than the lives of others, even the lives of children.

These figures are taken from United Nations Children's Fund

(UNICEF) reports. The overwhelming majority relate to poor countries.

·

5,900,000 children die each year before their 5th birthday - more

than 16,000 every day, almost one every 5 seconds.

·

2,600,000 new-borns die each year in their first month of life -

more than 7,000 every day, almost one every twelve seconds.

·

2,600,000 children under 15 are living with HIV.

·

2,400,000,000 people lack access to adequate sanitation (1 in 3

of the world's population).

·

1,000,000,000 children are deprived of services essential to

survival and development.

In November 2009 UNICEF released a special edition of their

annual 'State of the World's Children' report to celebrate 20 years of the

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, signed by world leaders

in November 1989 (referenced above). It discusses progress during that time and

with some irony its tone is one of optimism, in that the figures were

significantly worse in the past and there is every hope that they will continue

to improve in the future. Indeed later reports in the main show continuing

improvement, but so very slowly. In 1990 there were 12.5 million child deaths

before the age of 5, and in 2015 that had reduced to 5.9 million, indicating an

annual reduction rate of 3% per year over 25 years. If that rate of reduction

is maintained it will take another 80 years to reach the UK rate at 4 deaths

per 1000 live births, and in that time a further 180 million children will die.

If there was real determination on the part of the developed world to eradicate

those deaths and that suffering they could become history within just a few

years. Tragically there is no such determination.

Much of world apathy to these statistics comes from the

belief that poor countries raise far more children than they can afford, so

high levels of child death, though tragic, are inevitable. The underlying but

seldom-voiced view is that this undesirable state of affairs is the fault of

the populations themselves. This view misses a very important and dangerous

vicious circle - which can and must be stopped. An inability to save for old

age and an absence of welfare leaves poor people with only one choice if they

are to have any security in later life - a big family. Although many of their

children die, enough will hopefully survive to look after them when they can no

longer care for themselves. It makes perfect sense. The same situation existed

for exactly the same reasons in the UK and other now prosperous countries

before the Second World War. It is self-perpetuating because there are always

more mouths to feed than there are resources available to feed them. To stop it

requires better prosperity for the whole population, and better prosperity does

indeed stop it, as now prosperous countries can testify. Far from being

inevitable, high child mortality and unsustainable birth rates are both direct

effects of poverty. End poverty and those effects end with them. What is needed

throughout the world is a population that is stable and comfortably within the

world's capacity to support it, and for that we need a much more equitable

share of wealth throughout the world.

However, not only is the developed world not determined to

eradicate child deaths in poor countries it is preventing those countries from

helping their own populations by massive extraction of resources. This is

probably hard to believe given the developed world's widely trumpeted aid programmes,

but what isn't so widely trumpeted is just how much is extracted from poor

countries in comparison with what is given.

The countries involved are largely former colonies,

exploited in the past for their natural resources and now exploited again by

tax avoidance and repayment of crippling levels of debt - often incurred for

loans that gave no help at all to the populations that are saddled with their

repayment - they were stolen by corrupt politicians and officials of the

countries involved.

The rules of the game are set by the international economic institutions - the

International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organisation. Those

rules serve the interests of investors in rich countries at the expense of

people in poor countries (Stiglitz 2002 p214 and Stiglitz 2006 Chapter 8

pp211-244).

Those pursuing poor countries for debt repayment argue that

any form of relief creates moral hazard - it sends out the wrong signals to

potential and existing borrowers. A borrower who believes that the debt will be

reduced or forgiven has no incentive to ensure sound financial management and

will not take proper steps to prevent debt problems arising in the future. Furthermore,

it may be argued that borrowers do not have a chance to learn from their mistakes,

and continue to make the same mistakes that led to debt problems in the first

place. The fact that in many cases those shouldering the debts neither agreed

to take on the debts nor were even told about them by the corrupt rulers who

stole the money doesn't seem to count against those arguments with these

lenders - see also chapter 73.

This type of argument is typical of creditors who place all

the blame on debtors. Yet any lender in any circumstances takes a risk that the

debt will fail to be repaid, and they build this risk into the interest

payments that they demand - the higher the risk the higher the interest. A

fairer response is that rather than the debtor being to blame, the creditor

with a defaulted debt is either unlucky in that the risk materialised, or to

blame for not carrying out proper due diligence in the first place (Stiglitz

2006 p212). The truth is that lenders didn't do much due diligence; they felt

secure in the belief that a strong ruler would force the population to pay. Also many poor

countries are forced to borrow in foreign currencies, so they are always at the

mercy of interest rate changes in those currencies and can hardly be blamed

when they change to their severe disadvantage. Above and beyond all that

however is that arguments objecting to debt relief, when the alternative is

death and appalling suffering, are morally indefensible.

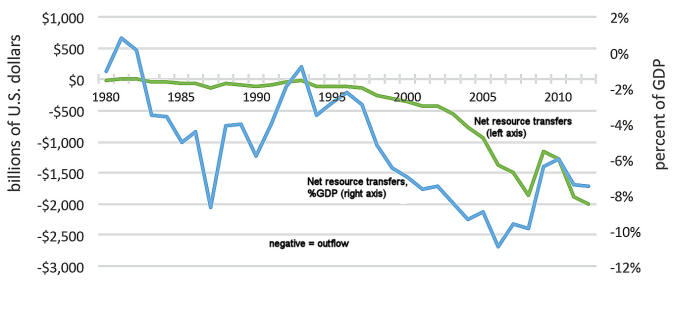

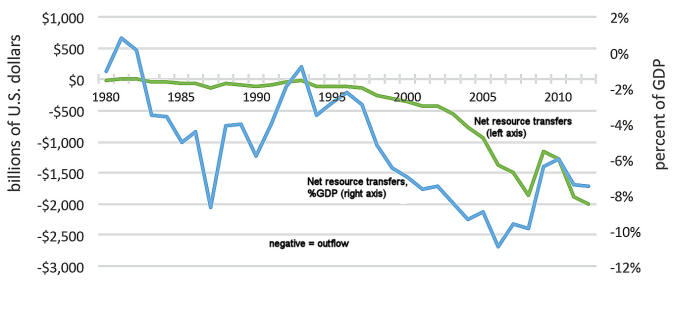

A report published in December 2015 provides a very

comprehensive analysis of all financial inflows and outflows from developing

countries,

and shows how much the rich world is extracting from them. Figure 62.1 is

repeated from that report and shows the annual outflows of wealth from developing

countries, which total a staggering $16.3 trillion (yes, trillion!) US dollars

since 1980. The GDP figures represent the combined GDP of developing countries.

To put this in perspective the report states (for the last decade):

"...for every dollar

of development assistance received by developing countries, more than ten

dollars disappear from these countries."

Figure 62.1: Annual wealth transfers from poor countries

to the rich. Source 'Financial Flows and Tax Havens' December 2015, by the

Centre for Applied Research, Norwegian School of Economics, Global Financial

Integrity, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Instituto de Estudos Socioeconomicos,

and the Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research.

The outflows consist of debt repayments and repatriated

investment income from rich country investments, but the biggest component, and

one that received little attention prior to this report, is unrecorded capital

flight transfers, mostly illicit, via tax havens and secrecy

jurisdictions. Of the $16.3 trillion total $13.4 trillion is unrecorded capital

flight, with $2.9 trillion in recorded transfers.

How can poor country populations ever escape their

poverty trap with a millstone like that hanging round their necks?

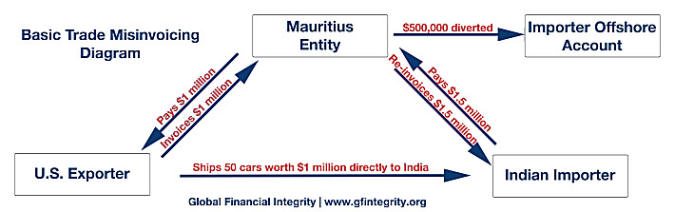

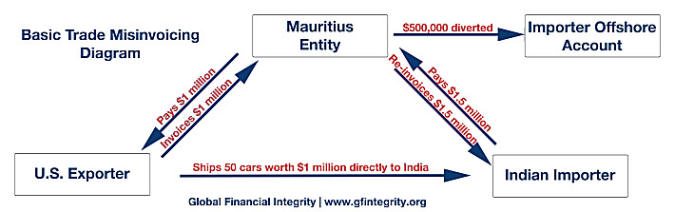

How do these illicit transfers work? A favourite trick is trade

misinvoicing. Here a company in the poor country imports goods from abroad

via an intermediary, who adjusts the invoice upwards to give the impression to

the authorities that the cost is much higher, and sends the excess to an

offshore account belonging to the importer. This is shown in figure 62.2.

Figure 62.2: Trade misinvoicing. Source http://www.gfintegrity.org/issue/trade-misinvoicing/

Another trick is transfer pricing by multinational

corporations, where they are able to lower taxable income in the poor country

to escape local taxation and deny the government revenue that is badly needed

for its own population. Multinationals also engage in other tax avoidance

strategies, all with the aim of enriching themselves at the expense of the poor

country. The report gives more details.

As Jason Hickel

pointed out:

Poor countries don't need charity. They need justice.

And justice is not difficult to deliver. We could write off the excess debts of

poor countries, freeing them up to spend their money on development instead of

interest payments on old loans; we could close down the secrecy jurisdictions,

and slap penalties on bankers and accountants who facilitate illicit outflows;

and we could impose a global minimum tax on corporate income to eliminate the

incentive for corporations to secretly shift their money around the world.

We know how to fix the problem. But doing so would run

up against the interests of powerful banks and corporations that extract

significant material benefit from the existing system. The question is, do we

have the courage?

This preamble highlights the worst and very ugly side of

globalisation, where those least able to cope are hardest hit. It shows the

level of ruthlessness that those who wish to change things are up against. Those

who are prepared to tolerate so much injustice in the pursuit of profit aren't

likely to stop by appeals to conscience, indeed they can't stop because those

with conscience are caught up in a system controlled by those without. To stop

them it will take strong and effective legislation enforced with determination

and backed up by stiff penalties for those responsible. We can't persuade the

perpetrators to stop because it's outside their power to do so, we must

persuade those who can make them stop - governments - and if we can't persuade

governments to do so then we must elect better governments.

The international market is the most unfettered of all

markets, and shows where such markets lead without strong and effective control.

Far from bringing prosperity to all they bring extreme wealth to some and

extreme hardship to very many more.

However, before we can work out how best to solve the

problems thrown up by globalisation, we have a lot more ground to cover in

order to understand international economics. So once again, let's get

started...