The economics of international trade, in spite of its

complexity, rests on some basic foundations:

There are many very significant advantages to be had from

international trade. Markets are much bigger so there is more demand for

products and greater opportunities for economies of scale, and higher levels of

specialisation are possible thereby improving efficiency. For consumers there

is a much greater choice of products, including products that are completely

unavailable in the home country. Consumers enjoy lower prices because of

increased levels of competition from a wider range of suppliers. The economy as

a whole also benefits. Exports bring in money that stimulates the economy without

having to rely on domestic demand, and imports bring in wealth at less cost

than would be required to produce locally. All this arises from the fact that

the effort to create surplus wealth differs greatly in different countries and

in different environments, so the UK buys bananas from Colombia because it

would be very costly for us to grow them here, and Colombia buys gas turbines

from the UK because it would be very costly for them to build them there.

However there are also disadvantages. Dependence on external

markets can backfire if for any reason imported foreign supplies dry up or

foreign consumption diminishes for exported goods. Domestic suppliers and their

employees can be especially hard hit in specialised industries such as coal

mining or shipbuilding when external competitors are able to undercut prices

significantly. In such cases there are great temptations for the home

government to apply protective measures such as import tariffs, limited quotas,

outright bans or home currency devaluations - known as trade barriers - in

order to protect workers, or to grant subsidies to enable home producers to

sell products competitively. If this happens similar measures tend to be

applied in retaliation by foreign trading partners in a tit-for-tat response,

damaging both sides of the trade. In effect there is a paradox of thrift at the

international level. Just as an individual can save effectively in isolation

but if everyone tries to save at the same time then their efforts are

ineffective because they stifle trade (see chapter 15), a country in isolation

that applies trade barriers will find them helpful, but if all countries try to

apply such barriers at the same time then they will be ineffective because they

stifle international trade. In the past trade restrictions were extensive and

commonplace, but in more recent times such barriers have been reduced

significantly, though not completely. Neoliberalism strongly discourages any

form of trade barrier and backs up that position using the 'Theory of

Comparative Advantage', which purports to prove that countries are always

better off by trading with each other rather than not, but as will be seen in

the next chapter there are some serious objections to the assumptions that

underlie that theory.

Problems also arise if there is a serious imbalance between

a country's exports and imports. If exports exceed imports then foreign

consumers benefit at the expense of home consumers, and if imports exceed

exports then debts are incurred to the exporting countries - see section 65.5 below.

Also spending on imports without balancing exports (more sellers of the

currency than buyers) depreciates the home currency which shrinks the economy

as spending power leaves the country.

For the world as a whole the sum of all international trade

is zero - every export from one country represents an import to another country.

Countries generally prefer to export rather than to import, because a country

that exports more than it imports is like an individual that creates more

wealth than he or she consumes - it increases wealth and power, but countries

that pursue that policy, as do Germany and China amongst others, can only do so

provided that other countries are willing to import their products.

An overall trade balance between exports and imports is a

healthy state, but it isn't necessary to maintain a balance with every country

that is traded with. Imports from China can be balanced by exports to Europe. This

is exactly the same as individual trade, where buying from one person can be

balanced by selling to another. I have a dreadful trade balance with the

owner of my local garage. I regularly pay for servicing and repairs from him

but he never buys anything from me - but neither of us loses any sleep over it!

A particular currency can only be used to buy wealth from

those who accept that currency - normally those within the issuing country, so

domestic currency normally only buys domestic wealth. Also wealth suppliers are

usually only willing to accept their own currency in exchange, whether the

buyer is domestic or foreign. In the absence of an international currency therefore

exchange dealing is a necessary element of international trade. This doesn't

apply to the same extent for reserve currencies - see 65.10.

With fiat currencies a country that imports more than it

exports borrows the difference from the exporter even though the goods are

paid for. This is not obvious, but imagine two desert islands, one that

specialises in growing coconuts and the other in growing mangoes. They agree to

trade coconuts for mangoes. Now if the first island imports mangoes before its

coconuts are ready, what can it trade with instead? The answer, in the absence

of anything else of equivalent value, can only be a promise to pay, which is

precisely what fiat money is. In other words the first island pays for the

mangoes in money - coconut currency - which, being fiat money doesn't have

intrinsic value (if it did it would be an equivalent value export and no debt

would arise) and is therefore nothing more than a promise to pay the equivalent

back in coconuts in the future. In the meantime it is in debt to the second

island. It is the very fact that the goods are paid for in fiat currency that

creates the debt. Note that in this case the local currency of the importer

is acceptable to the exporter, which is important because whenever this can be

arranged it gives the debtor a great deal of control over the debt. The

alternative, if the exporter won't accept the importer's local currency, is for

the importer to borrow the exporter's local currency and pay for the goods with

that. This is much less favourable to the importer because now the exporter has

control over the debt. Both cases involve borrowing by the importer.

In this simple example there is a difference in these two

ways of borrowing. If the person who imports mangoes pays in coconut currency

then it is the importing country that has borrowed and the exporting person

who has lent. The importing person has given coconut currency to the exporter

and for the importer the transaction is complete. The exporter can use it to

buy coconuts from anyone in the coconut country so it is the country as a whole

that carries the obligation to send coconuts to the exporter rather than any

particular person in that country. In effect the exporting person has lent

mangoes in return for a coconut IOU from the importing country. If the

importing person borrows currency from the exporting country then it is the

importing person who has borrowed and a lender - a third party -

in the exporting country who has lent. In this case the importing person has

borrowed mango currency and used it to pay the mango exporter for mangoes, for

whom the transaction is complete. The importing person retains an obligation to

the lender, and can only discharge it by selling coconuts for mango currency

and repaying the loan with that.

The real world doesn't work in either of those ways. Most

currencies float freely against each other and are traded on foreign exchange

markets, where currency dealers continuously balance sales and purchases of currency,

changing the offer and bid prices in order to maintain that balance as closely

as possible. In that way the individuals doing the exporting and importing

don't need to bother about lending and borrowing, once the importer has

arranged for the home currency to be exchanged and paid to the exporter the

transaction is complete for both. In this case the importing country borrows

and the exporting country currency dealer lends. This type of

exchange is explored in more detail in chapter 68. With countries that trade

without floating currencies, China and the US for example, the importing

country (US) buys in its own currency, which is exchanged by the central bank

of the exporting country (China) for its home currency, so again the importing

country borrows and the exporting country lends. Trade between the US and China

is considered further below.

With fiat currencies a country that imports more than

it exports must borrow the difference from the exporting country.

Let's consider further the point about debt in the

importer's home currency being acceptable to the exporter. At the present time

the US - the importer - is heavily in debt to China, because China holds

massive quantities of the US home currency (largely in the form of government

debt - treasury bills and bonds) in return for the goods that it has sold to

the US.

At any time the US can reduce the wealth value of this debt by engineering a

depreciation of the dollar - making it worth less in terms of tradable wealth -

or by reducing the value of its bonds. It can depreciate the dollar by creating

and circulating more dollars, thereby encouraging inflation; it can sell dollar

currency in the market and buy other currencies, thereby reducing the demand

for dollars and hence the value of the dollar; or its central bank can sell

treasury bonds in the secondary market thereby directly reducing the value of

China's bonds. All these actions have the effect of reducing the US wealth debt

to China, whereas China can do very little on its own to maintain the value of

the dollar. Ironically China has more economic interest in maintaining the

value of the US dollar than does the US itself.

Conversely if the importer's debt is in the exporter's or

some other foreign currency, then the value of that currency is out of the

hands of the importer. If its value increases then the debt will grow,

sometimes to enormous proportions. This has happened in the past in the case of

developing economies and was ruinous for them - see chapter 73.

When gold was used for direct international transactions no

debts were incurred because the same value of wealth was both exported and

imported in each transaction, one side in gold and the other in goods or

services.

Nowadays all countries trade with other countries, and all

use fiat currencies. There must therefore be arrangements for exchanging

currencies with other currencies, but these arrangements differ for different

countries.

Most countries allow their currencies to be freely traded

with other currencies, and there are two types of free trade. The first and now

the most common is floating currencies, where the relative value of each is

determined in the foreign exchange market by supply and demand. Values of

floating currencies change all the time in response to many factors - see

chapter 67 subsection 67.4.2. The other type of free trade is fixed or pegged

exchange rates, where the rate is fixed by the government or central bank of

the country in question relative to a stronger currency such as the US dollar

or Euro. In this case the country's central bank holds a quantity of the

stronger currency, and uses it to buy or sell its own currency to change the

level of demand for it and thereby to maintain as far as possible the fixed exchange

rate. If the amount of buying of its own currency by the central bank is

excessive it’s because other people are selling it excessively – more importing

than exporting - so the currency is devalued (the exchange rate moves downwards

- less of the strong currency for one unit of the domestic currency) or, for

excessive selling – more exporting than importing - it is revalued (the exchange

rate moves upwards - more of the strong currency for one unit of the domestic

currency).

Countries that don't allow their currencies to be freely

traded arrange exchanges at state level by the government or central bank. Imports

or exports to and from the country are paid in an external currency, usually

the US dollar, and the state manages the exchange with the domestic currency. China

is the most obvious case in point and avoids free exchange so as to keep the

value of its own currency low (it would rise significantly if traded freely

because China has a large excess of exports over imports). Chinese international

trade is discussed further in section 65.8.

Even though currencies float, at any point in time they are

tied together by the value of internationally traded wealth. If any currency is

even slightly out of balance in this respect arbitrageurs - traders who

make profits by searching for and exploiting price differences - rapidly bring

them back into balance again. For example if zinc is trading at £1,000 per

tonne and also at $1,500 per tonne, but the exchange rate is $1.4 per £1, a

trader can buy 100 tonnes of zinc in the UK for £100,000 and immediately sell

it for $150,000 in the US (transport costs can be ignored - see below), then

exchange the $150,000 for £107,143, making a risk-free profit of £7,143. But

this opportunity won't last long because every time dollars are sold and

sterling bought the dollar is made weaker and sterling stronger, so the

exchange rate soon approaches $1.5 per £1 at which point balance is restored. Traders

in these markets buy derivatives (futures) linked to commodities rather than

commodities themselves to avoid having to deal with physical goods. Arbitrageurs

are also on the lookout for any anomalies between currency values themselves

that are offered by the various brokers. Again any opportunity to make money is

soon taken and as before the effect is to keep currency values in balance.

Imbalances between imports and exports tend to self-correct,

provided that either a common currency is used or currencies are freely

exchanged. If these conditions aren't met, such as when an exporting country

retains the currency of the importing country, then the self-correcting

tendency is absent. When these conditions are met a country that exports more

than it imports finds that its exports become dearer in importing countries so

export demand for them drops, and imports from foreign countries become cheaper

so domestic demand for them rises, as explained below. The opposite happens if

a country imports more than it exports. However, in order to work properly

there must be adequate spare capacity available to expand export production

when foreign demand rises.

Consider the case of a common currency such as gold, with

two trading countries A and B, A exporting to B more than it imports. With an

excess of exports gold is accumulated in A and diminished in B. An accumulation

of gold tends to depreciate its value in relation to A's home wealth, so in A

prices rise, which makes exports to B dearer for B and imports from B cheaper

for A. Conversely for B gold is in short supply so its value in relation to its

home wealth rises and prices fall, further strengthening the effect of making

imports from A dearer for B and exports to A cheaper for A. Therefore exports

from A diminish and imports to A increase, tending to correct the earlier

imbalance.

With the same two countries using free exchange and floating

rates there is more demand for A's currency when A exports more than it imports.

B has to sell more of its currency to buy A's currency than A has to sell to

buy B's currency, so A's currency increases in value relative to B's, and

exports from A again become dearer for B and vice versa, again correcting the

earlier imbalance. With free exchange and fixed rates B has to sell more of its

reserves of A's currency in order to buy back its own currency from importers

who sell it to buy A's currency, so as to maintain the value of its currency. Losing

reserves prompts B to cut back on imports and promote exports, thereby

correcting the imbalance, or, if it doesn't, then eventually it runs out of

reserves and is forced to devalue its currency with the same result as with

floating exchange rates, again tending to correct the imbalance.

Another condition can lessen the imbalance-correcting effect

however and that is when populations are free to move easily from one country

to another. In this case people who are able to move tend to do so to enjoy the

greater prosperity available in the richer country - generally the one with

excess exports. These people are generally wealth creators so a country that

finds demand for its exports rising is less able to meet that demand. Free and

easy population movement between countries is not common in the modern world

though an exception is for populations within the European Union. This is

considered in chapter 72.

The effect doesn't occur if there is no common currency and

currencies aren't freely exchanged. For example China exports goods to the US

but doesn't allow its currency, the renminbi,

to appreciate against the dollar as it would do if it was freely traded. Instead

China's central bank handles all renminbi currency exchange on behalf of the

government by taking dollars from US importers and investing them in US

securities, and paying out renminbi to its export workers, which it obtains by

borrowing from its own population at low rates of interest. The Chinese

population have little in the way of job or health security and so save

heavily, but have very restricted investment opportunities available other than

lending to the government. The exchange rate between dollars and renminbi is

thereby completely controlled by China's central bank, and that prevents the

dollar from falling in value against the renminbi but builds up massive

investments for China in the US. This explains why both China and the US are

heavily in debt - China is in debt to its own population and the US is in debt

to China. The perverse effect is that the population of China, still very poor

in spite of the country's recent growth, lends money in great quantities to the

US (via the Chinese central bank), one of the richest countries in the world.

Most trade is carried out within a country's domestic

economy. Very often, relatively poor countries whose currencies have low

valuations have much cheaper domestic prices than the exchange rate would imply.

This is because the exchange rate reflects the value of internationally traded

wealth, not wealth that is only traded domestically. Most services are purely

domestic and many locally sourced products, especially when perishable,

are only available in the domestic market. In order to take account of these

factors another comparative rate, more realistic in terms of the value of a

currency to its own people, has been devised, called Purchasing Power Parity

(PPP). This reflects the relative values of different currencies when used to

buy representative baskets of goods. For example in 2015 the international

exchange rate between Mexican pesos and US dollars was 16 pesos to the dollar,

whereas for a representative basket of goods in each country one US dollar

would buy the same in the US as 8.4 pesos would buy in Mexico, showing that in

PPP terms the peso is worth almost twice the international exchange rate. The OECD

publishes tables of PPP values as well as exchange rates. In 2011 the

World Bank published a report stating that the size of the world economy was

$90 trillion in terms of PPP but much less at $70 trillion in terms of exchange

rates, indicating the higher value of domestic wealth when calculated in terms

of a common currency based on domestic exchanges rather than on international

exchanges.

A reserve currency (also known as an 'anchor currency',

'hard currency' or 'safe-haven currency') is a currency that is held in

significant quantities by governments and institutions as part of their foreign

exchange holdings. The reserve currency is commonly used in international

transactions because it is acceptable to many other countries in addition to

their own domestic currency.

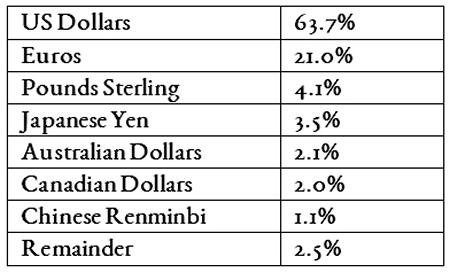

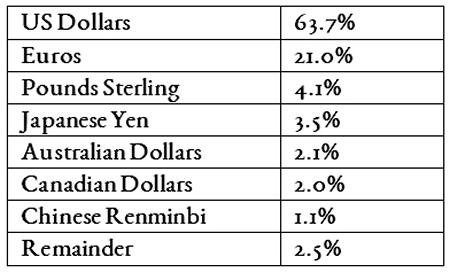

The distribution of reserve currency holdings at the end of

2014 were as follows:

Table 65.1: Reserve currency distribution in 2014

As can be seen the US dollar is by far the world's most

favoured reserve currency, meaning that central banks hold significant

quantities of US dollars in preference to any other currency. Additionally many

commodities are bought and sold principally in US dollars because it's easier

to trade in a common currency, and after the Second World War the US dollar was

the only viable currency for this purpose and it has retained that position

ever since. When exchanging less common currencies it is usually easier to

change the first for dollars and then change the dollars for the second,

because all exchangeable currencies can be converted to and from dollars

whereas they can't all be converted to or from each other. Chapter 71 deals

with reserve currencies in more detail.