Free capital movement - the ability to buy and sell foreign

assets including currencies and debts freely and in any quantity - was one of

the changes ushered in after the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement. It is

strongly supported by neoliberal ideology.

The damage that can be done to poor countries when capital

is allowed to move freely across borders has been discussed in the last chapter,

but it also damages rich countries. Keynes and White recognised only too well

the dangers during the Second World War when designing the post-war

international trading arrangements - see chapter 67 section 67.2. What they

wanted was to stimulate trade in goods and services, which benefits everyone

provided that those benefits are shared fairly, and they saw clearly that free

movement of capital can and does damage that trade. Keynes and White argued

that freedom of movement for capital conflicted both with a nation state's

freedom to pursue economic policies based on its own domestic circumstances -

for example by stimulating a sluggish economy or by calming a racing economy,

and also with the semi-fixed exchange rate system that was widely agreed to be

important to maximise international trade in goods and services. Since then

White has been forgotten and everything that Keynes ever said and wrote is

treated with contempt by neoliberals.

Many benefits are cited for free capital movement: money

can be allocated to where it can do the most good; it enables investment in

developing countries to aid their growth; it allows financial markets to

expand; and it reduces the cost of capital because of increased lending

competition. Before the crises that affected developing countries in the 1980s

and 1990s it was widely regarded as unarguably beneficial, but since then it is

becoming increasingly controversial, with even the IMF accepting that it might

not be the universal good that it had believed it to be following the Bretton

Woods breakdown.

Joseph Stiglitz tells us what's really going on:

As a matter of simple economics, the efficiency gains

for world output from the free mobility of labor are much, much larger than the

efficiency gains from the free mobility of capital. The differences in the

return to capital are minuscule compared with those on the return to labor. But

the financial markets have been driving globalization, and while those who work

in financial markets constantly talk about efficiency gains, what they really

have in mind is something else-a set of rules that benefits them and increases

their advantage over workers. The threat of capital outflow, should workers get

too demanding about rights and wages, keeps workers' wages low. (Stiglitz 2012

Chapter 3)

The crux of the matter is that all economies depend on the

circulation of money, as was shown in chapter 14. Anything that threatens that

circulation threatens wealth creation, and wealth creation is what everyone

depends on because we all need to consume wealth both to stay alive and to live

a normal life. The free movement of capital across borders allows money to be

transferred to where it can 'do the most good' - i.e. the most good for the

owner of that capital

- which is not at all the same thing as the most good for trade or for

individual countries.

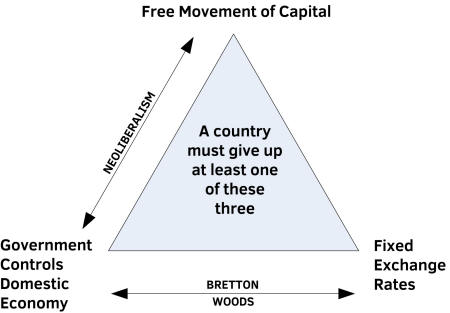

It was recognised as a result of bitter experience after

capital controls were loosened that there are three policies that can't all

operate at the same time:

i.

free movement of capital;

ii.

government control over the domestic economy (ability to set interest

rates and control domestic demand); and

iii.

fixed exchange rates.

At most only two of these three can exist together - this is

known as The Impossible Trinity

(and also the Monetary Trilemma), shown in figure 74.1.

Figure 74.1: The Impossible Trinity

Before it was recognised there were several financial crises

as countries attempted to maintain all three. The UK example occurred on 16

September 1992 when it was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism

(ERM) by the action of 'the markets' on what became known as 'Black Wednesday'.

To see why it is true imagine the UK attempting to adopt all

three policies at the same time with a sterling interest rate set by government

at 5%. If in the US the interest rate is 10%, UK investors sell their UK

investments, exchange the money for dollars at the prevailing rate and invest

it in US bonds because they get a much better return on their money. As UK investors

continue to do this UK investments fall in value and therefore the interest they

pay rises in real terms, until it is the same as the US interest rate. Hence

the UK government has lost control over UK interest rates, which are forced to

match the dollar interest rate. In fact but for different expectations of

inflation in different currencies and abilities of governments to repay, all

interest rates would have to match each other with free capital movement and

fixed exchange rates.

What most countries have chosen to give up since Bretton

Woods is fixed exchange rates. China is an exception, giving up instead free

movement of capital but keeping control of interest rates and exchange rates. This

is the same as applied during the Bretton Woods era. This is significant.

The economy that has grown the most (now world number

two) and lifted the most out of extreme poverty during the neoliberal era is

China's, but China plays by Bretton Woods' rules, not neoliberal rules (Chang

2008 p27).

However it isn't as simple as that, as Rodrik shows (Rodrik

2012). When Bretton Woods collapsed and floating exchange rates took over, it

was thought that rates would stay fairly stable, with supply and demand for

traded goods and services setting the price in terms of exchange rate as they are

supposed to do in other markets. What hadn't been considered was the effect of

setting up a new gambling forum with speculators able to bet on exchange rate

movements in the hope of making profits. Even that wouldn't have mattered so

much if gamblers were completely independent of each other as they are assumed

to be for market predictability - see chapter 34. But, as already discussed in

chapter 57, financial markets are anything but independent; they are driven

much more by what others in the market are doing than by objective assessment

of value. As time progressed and speculation mushroomed, any exchange rate

signals that there might have been from trade in wealth were drowned out by

speculative transactions. In 2007 the daily volume of foreign currency

transactions had risen to $3.2 trillion, whereas the volume of wealth trade was

$38 billion (Rodrik 2012 p107) - eighty-four times as much speculation as

genuine trade!

Another factor is that with free capital movement the

raising or lowering of interest rates has a much smaller effect on the domestic

economy than it would with capital restrictions. This was discussed in chapter

70 but in summary a government induced rise in interest rates, intended to slow

a racing economy by reducing the money supply, will instead cause an inrush of spending

from abroad for investment purposes, thereby offsetting much or even all of the

intended decline.

Therefore although the triangle gives the impression of

three equally balanced factors, the free movement of capital is by far the most

dominant.

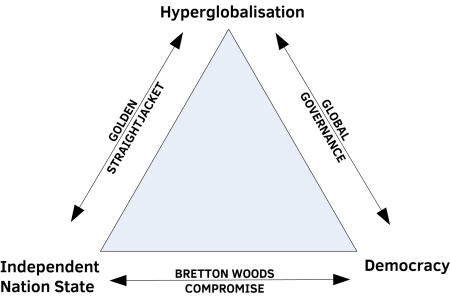

Rodrik expresses this as another triangle, but here, instead

of merely free movement of capital he takes it further, calling it 'hyperglobalisation'

- which is the situation that neoliberalism drives us towards, consisting of:

·

free movement of capital across national borders;

·

opening up to foreign trade and investment of all national

markets;

·

enforcement of intellectual property rights across the world;

·

disempowerment of national bodies for economic policy-making and regulation

of health, safety and welfare standards;

·

disappearance or privatisation of social insurance;

·

low corporate taxation;

·

removal of social compacts between business and labour; and

·

subordination of national developmental goals to market freedom

(Rodrik 2012 Chapter 9).

The other two factors are Democracy, where government

authority derives from the will of the electorate, and an Independent Nation

State, where there is national rule, but any thought of government controlling

its own economy has gone. This is The Political Trilemma of the World

Economy, shown in figure 74.2.

Figure 74.2: Political Trilemma of the World Economy. Source:

Rodrik 2012 p 201.

If we have hyperglobalisation then all matters relating to

money and markets are determined at the world level and can't be set

independently by an individual country. This is the same as a single region

within a country, which must abide by the monetary policy and the markets of

the country as a whole. The only way in which a nation state can be governed in

these circumstances is by maintaining global monetary and market rules even

when its population is severely disadvantaged by them. In effect the government

is a dictatorship.

Rodrik cites Argentina between 1990 and 2002 as a good

example, beginning with Cavallo's tying of the country's currency, the peso, to

the US dollar in order to bring confidence back in its economy. At the same

time privatisation and deregulation were accelerated, and the economy was

opened up to world trade. Things went very well indeed for several years until

the Asian crisis in the late 1990s, when investors' appetite for emerging

market investments suddenly dried up. This was followed by Brazil devaluing its

currency by 40% in 1999, thereby picking up exports at Argentina's expense. Soon

the peso was under severe pressure and Argentina's creditworthiness collapsed. Strict

austerity policies were applied in 2001 in an effort to shore up foreign

investor confidence, but the internal strife that was unleashed proved decisive.

There were strikes, riots and looting. Eventually the government was forced to

abandon its monetary policies; it froze foreign bank accounts, defaulted on

foreign debt, re-imposed capital controls and devalued the peso. In short democracy

won the day over hyperglobalisation (Rodrik 2012 pp184-187).

Keeping hyperglobalisation and the nation state is known as

the golden straightjacket, where the state is forced to follow the

dictates of the world market. During hard times when productivity is low it can

only do so by impoverishing the population. Democracy is sacrificed in these

circumstances because a democratic country wouldn't tolerate the harsh

conditions that world markets can inflict. The name evokes the gold standard

that tied all economies together in this way before the First World War, when

fully democratic politics hadn't yet emerged. In effect this is the situation

that European countries using the Euro are in with respect to the European

Union as a whole. Individual nation states still exist but they have largely lost

democratic control over their own economic affairs. The conflict between

democracy and European hyperglobalisation has been most sharply seen in Greece,

where the population is reacting with great hostility to the straightjacket

that they are forced to wear. The European special case was considered in

chapter 72.

The Bretton Woods compromise retained the nation state and

democracy, but severely restrained globalisation in terms of free capital

movement and other international factors. The focus then was on trade in goods

and services, and it worked very well until the Nixon shock in 1971 when the

dollar was unpegged from gold. Had Keynes' Bretton Woods proposals been adopted

instead of White's we would have retained the benefits in terms of world trade

and democracy, and there would have been no Nixon shock - see chapter 84.

The other alternative is full globalisation, with democracy,

a world government, world central bank, world judiciary and robust global

regulatory institutions. This is an appealing prospect in many ways but the

difficulties that would be faced are enormous. In particular if one or more

countries wanted out because they strongly disliked the rules then how could

they be stopped? Would the rest send in armed forces as in colonial days? I

doubt that there would be widespread support for such a measure - I certainly

hope there wouldn't. A world government would need very strong and lasting

world support to retain legitimacy. However a world government would have

responsibility for all people, so any who were disadvantaged as a result of

changes in trade patterns and improvements in technology would be looked after

(hopefully) until they could find new employment. In addition to this global

safety net there would be a global lender of last resort, a global monopoly

watchdog, and a series of global regulators for all health and safety aspects

of the global marketplace. This is the same as happens in existing developed

countries where all such governance measures are in place in some form.

At present we have a world economy that mirrors

practically all the characteristics of a single country economy, but without

any of the safeguards.

As Rodrik said:

...markets and governments are complements, not

substitutes. If you want more and better markets, you have to have more (and

better) governance. Markets work best not where states are weakest, but where

they are strong. (Rodrik 2012 p xviii)

Rodrik is right and we need to face the problem that emerges

from his insight. We must recognise that the more we drive towards

hyperglobalisation the more we drive out democracy. Allowing the rules to be

set by strong business interests, i.e. undemocratically, is dangerous. Not only

are the majority of people severely disadvantaged for the benefit of the very

few, but there is no way that such a system can face up properly to the social

dangers posed by climate change. Private interests will never voluntarily pay

for public goods or pay to avoid public or environmental harm, they will and

indeed can only pay for things that deliver private profits. On occasions when

they do appear to pay for such things voluntarily they are really paying to

enlist public support so as to enhance profits.

To quote Rodrik again:

So we have to make some choices. Let me be clear about

mine: democracy and national determination should trump hyperglobalisation. Democracies

have the right to protect their social arrangements, and when this right

clashes with the requirements of the global economy, it is the latter that should

give way. (Rodrik 2012 p xix, his italics.)

Voices in favour of restrictions on the free movement of

capital are becoming more widespread. A report by the New Economics Foundation written on behalf

of the Green New Deal Group

stated:

In June 2005, the Bank for International Settlements,

perhaps one of the most conservative institutions in the financial system,

addressed the problem of global imbalances and suggested that the international

financial system could 'revert to a system more like that of Bretton Woods'. It

added that 'history teaches that this would only work smoothly if there were

more controls on capital flows than is currently the case, which would entail

its own costs.'

Such controls would not be hard to police. Large

financial movements are tracked already by national authorities, in the name of

'anti-money laundering measures'. They use the technology that makes possible

almost instantaneous money transfers and split-second dealings in cash and

securities around the world. Moreover, there is a low-tech reinforcement for

this high-tech equipment. Contracts or deals entered into in offshore

jurisdictions, or anywhere else, in defiance of financial controls could be

declared void in British law. This 'negative enforcement' is highly attractive.

It requires no police; it relies simply on British courts not doing something,

i.e. recognising and enforcing financial arrangements made without

authorisation.

Both these methods of enforcement also give the lie to

the objection that financial controls can work only with international

agreement.

Michael Meacher cites the above in his book (Meacher 2013 p172)

as well as a BoE report issued in December 2011. Meacher states:

A Bank of England paper released in December 2011 points

out that under the Bretton Woods system (1944-71) of fixed exchange rates and

capital controls, compared with floating exchange rates and deregulated capital

flows that followed after 1980, growth was higher, recessions were fewer and

there were no financial crises. It notes that governments were able to pursue

their domestic objectives without the constant fear of destabilising flows of

hot money. The paper concludes that 'the period stands out as coinciding with

remarkable financial stability and sustained high growth at the global level.'

In terms of trading balance enabling governments to deliver strong

non-inflationary growth, the capacity to allocate capital efficiently and the

achievement of financial stability, the paper argues that 'overall the evidence

is that today's system has performed poorly against each of these three

objectives, at least compared with the Bretton Woods system, with the key

failure being the system's inability to maintain financial stability and

minimise the incidence of disruptive sudden changes in global capital flows.'

The free movement of capital hands wealthy people and

corporations a very strong lever over governments in that they can move their

wealth out of the country very easily and thereby damage national economies. Fear

of this power forces governments to respond to their interests rather than the

interests of the society that elected them.