STATE OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY

By Various Authors

Three biggest credit ratings agencies, Moody’s, Fitch and S&P, are shocked at state of South Africa's economy

The Finance Ministry says the big three credit ratings agencies are in "shock" at the state of South Africa’s economy.

Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba spoke to all three agencies Moody's, Fitch and S&P global ratings over the phone after his maiden medium-term budget.

His spokesman Mayihlome Tshwete said they asked specific questions about the wage bill, state-owned companies and low growth.

Gigaba’s painted a bleak picture of the situation the country is in on Thursday, giving what he called an honest assessment of the challenges it faces.

He’s also revealed the revenue shortfall is expected to come in at R50,8 billion this year, severely eroding South Africa’s financial position.

The government’s hand has been forced, because without selling off some assets the bailout for SAA and the Post Office of nearly R14 billion would have blown the budget, sending a disastrous signal to investors and ratings agencies.

Gigaba said: “Additional appropriations of R13.7 billion to recapitalize the SAA and the Post Office are being made. These have been partially offset using the contingency reserve, a shortfall of R13.9 billion remains to ensure the expenditures ceiling is not breached. We have decided to expose a portion of government’s Telkom shares; we don’t take this decision lightly, but we’ve had to.”

The bailout and an expected tax revenue shortfall for this year of a whopping R50,8 billion means the budget deficit will widen to 4.3% of GDP this year, against a February budget target of 3.1%.

All Share Index vs Mining & Resources Index

A glance at the chart below will reveal the continuing demise of South Africa’s once powerful economic engine – mining. The Mining & Resource Index now flatlines against the All Share Index.

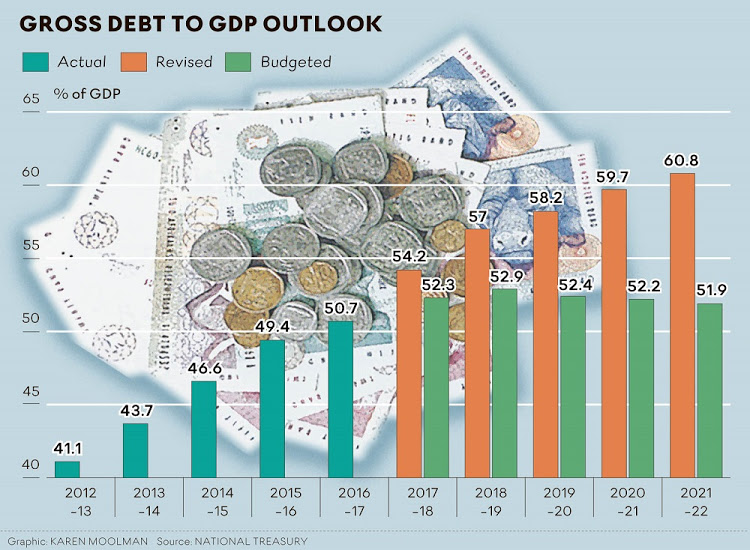

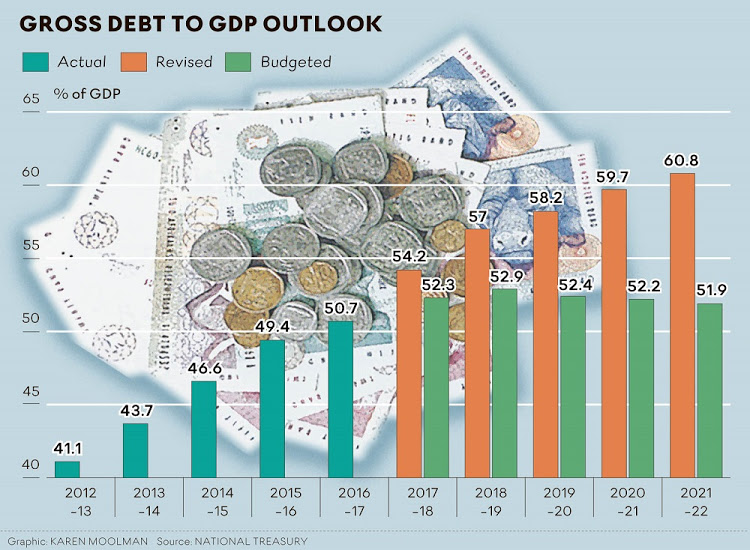

Debt vs Gross Domestic Product

In 2016 South Africa recorded government debt equivalent to 51.70 percent of the country's Gross Domestic Product. Government Debt to GDP in South Africa averaged 38.65 percent from 2000 to 2016, reaching an all-time high of 51.70 percent in 2016 and a record low of 27.80 percent in 2008.

BizNews Alec Hogg ‘s interview with Finance Minister Nene revealed:

Government is already paying more than R100bn to service its debt. And now by Treasury ‘s own estimates, that rises to more than R150bn in three years. Nene is mindful of the challenge this poses for his future Budget addresses. Hogg said ‘my notes show that at one point yesterday Nene said that unless something is done to stop the debt growing, annual interest will soon overtake social grants’.

He is doubtless reminded of this fact when he pores over the graphic above – the scariest in the entire Budget pack. Only two things will fix the problem: economic growth and no more borrowing. The first requires a Government that is prepared to address a range of structural issues bedevilling the SA economy – not just Eskom. The second means running a balanced Budget, a near impossible task in a developing country ‘.

Latest Debt vs GDP Budget projections show that the Government remains borrowed until 2019 at higher than 50,0%.

By 1994 the Apartheid Government had borrowed against South Africa‘s future in attempting to uphold the untenable principle of separate development. At that time, with a debt ratio of about 50% of GDP, our children were faced with a future of repaying their errant parents borrowings well into the future.

Under the conservative stewardship of first Nelson Mandela and after him Thabo Mbeki, Finance Minister Trevor Manual managed to reel in excess expenditure and prudently repay the country ‘s debt.

By the time Jacob Zuma came to power in 2007, Manuel had performed a minor miracle in reducing the National Debt to Gross Domestic Product to below 30%. South Africa was once again looking attractive to foreign investors and Foreign Direct Investment, upon which the South African Economy critically relies, was looking bullish.

With Zuma at the helm the wheels came off.

Now in 2017, with a Debt to GDP ratio back up over fifty percent, our children‘s‘ futures are once more in hock. Additionally, with Zuma relentlessly pursuing a nuclear build program, which the country does not need and certainly cannot afford, our kids, Black, Coloured, Asian and White, do not have a future in South Africa.

SA’s public sector debt has exceeded levels last seen at the advent of democracy and indicates an economy on its knees.

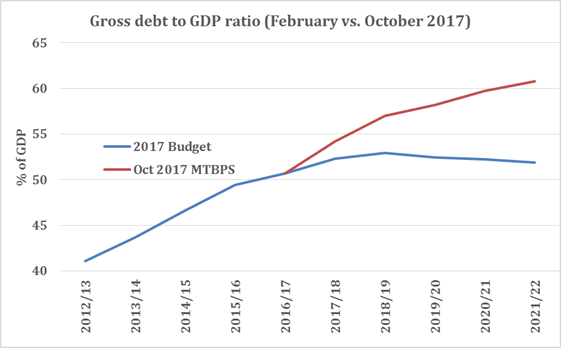

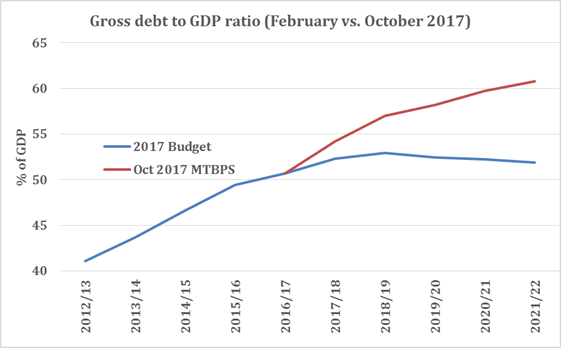

Debt and debt-service costs are projected to rise drastically over the next three to four years. On Wednesday, the Treasury forecast an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio to 60% by the 2020-21 fiscal year. In 1993-94, the ratio was 48.3%.

Standard Bank chief economist Goolam Ballim said the medium-term budget policy statement revealed that SA’s political establishment had no clothes. "The finance minister was impressively candid about SA’s dire situation. This was, however, matched by his inability to show a path to resolution."

Debt-service costs will remain the fastest-growing category of public-sector expenditure over the next three years, crowding out social and economic spending.

Over the medium term, the gross borrowing requirement — the sum of budget deficits and funds required to refinance debt that matures during a year — will be nearly R1-trillion, from R248.3bn in 2017-18.

Gross loan debt is expected to increase from R2.5-trillion, or 54.2% of GDP, in the current fiscal year to R3.4-trillion, or 59.7% of GDP, in 2020-21.

"SA’s economy is paralyzed singularly because of the political dysfunction," Ballim said.

ADVERTISING

"Until we glean who the next ANC leadership is going to be, we are going to remain paralyzed. Private-sector capital and investment is going to remain in recessionary mode."

Ballim said the budget had provided "no practical, plausible and implementable measures" to calm the markets. "If anything, the minister laid bare the increased propensity for credit ratings downgrades or perhaps he subtly ceded the resolution to the politicians and particularly the ANC."

John Orford, portfolio manager at Old Mutual Investment Group’s MacroSolutions boutique, said bonds had weakened in the run-up to the budget.

Bond yields rose 35 basis points over the past month.

Until we glean who the next ANC leadership is going to be, we are going to remain paralyzed

"That shows there was some nervousness in the market about what to expect in the budget," Orford said.

"What we now see is a projection of debt to GDP rising sharply to 54% from the current level in 2017-18 but continuing to rise through the next four years and ending up at 61% of GDP," Orford said.

While there might be certainty following the ANC elective conference "on face value, it’s a very negative budget for the bond market", he said.

"We see that in the reaction in bonds. Bond yields are up. The rand touched R14/$ and came back a little."

Orford said it was a poor budget statement. "It doesn’t credibly show an attempt to consolidate government’s debt at sustainable levels. It’s possible the budget in February may deliver something.”

SA may need help from IMF if state debt reaches danger levels

by Justin Brown

October 25, 2017

Government debt could increase by more than 50%, or by R1.2 trillion, to danger levels over the four fiscal years ending March 2021 – and if this comes to bear it could ultimately lead the country to seek international help from organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba today presented his first Medium Term Budgetary Policy Statement (MTBPS) to parliament. He was appointed as finance minister on March 31 after President Jacob Zuma reshuffled his Cabinet and fired Pravin Gordhan.

The MTBPS is a key fiscal statement and provides fiscal forecasts over a three-year time frame including estimated economic growth, tax revenue, expenditure, the budget deficit and the level of government debt.

Gigaba’s MTBPS warned that gross national debt is projected to continue rising, reaching over 60% of GDP by March 2021 from over 50% earlier this year.

Debt of 60% of GDP is a red-light level for government finances while debt of 65% to 70% of GDP could see the government forced to seek international help from organizations like the IMF.

“Gross loan debt is expected to increase from R2.5 trillion or 54.2% of GDP in 2017/18 to R3.4 trillion or 59.7% of GDP in 2020/21. Absent higher economic growth or additional steps to narrow the budget deficit, the debt-to-GDP ratio is unlikely to stabilize over the medium term.”

“In this context, government faces difficult choices,” the National Treasury said.

“South Africa’s stated policy aspirations and its social needs far exceed available public resources. Moreover, there is little space for tax increases in the current environment,” the National Treasury added.

In another shock for investors, National Treasury said that the recapitalization of SAA and the South African Post Office put the government’s expenditure ceiling at risk of a R3.9 billion breach.

“Government is considering the disposal of assets to offset these appropriations during the current year,” the National Treasury said.

Treasury has cut its forecast for local economic growth.

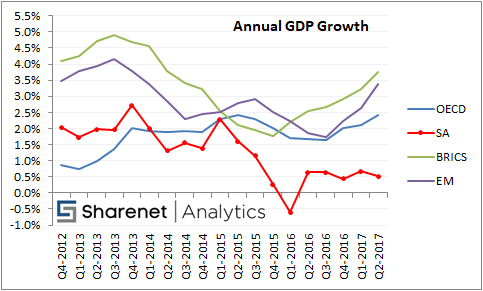

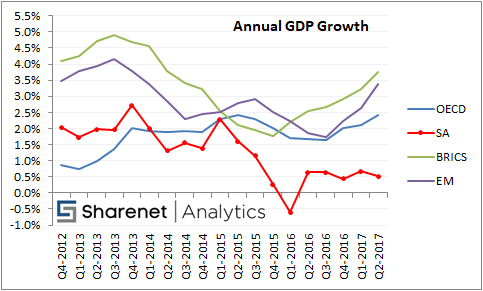

For this year the government is forecasting the economy to grow by 0.7% from its forecast of 1.3% made at the February Budget Speech.

A growth rate of 0.7% for 2017 means South Africa has the slowest rate of growth – along with Brazil – among all major developed and developing economies worldwide.

The world economy is expected to grow by 3.6% this year and on average the developing world is forecast to expand by 4.6% in 2017.

For 2018, the National Treasury is forecasting growth to be 1.1% followed by growth of 1.5% in 2019 and 1.9% in 2020.

This compares with local population growth of about 1.6%.

As a result, the National Treasury said that its macroeconomic projections implied that per capita income, which indicates the average wealth per citizen, would stagnate for years to come.

“Unless decisive action is taken to chart a new course, the country could remain caught in a cycle of weak growth, mounting government debt, shrinking budgets and rising unemployment,” the National Treasury said.

Debt service costs are forecast to be the fastest rising item in the government budget, increasing on average by 11% from the 2018 fiscal year through to the 2021 fiscal year. This increase compares with average increase in government expenditure of 7.3% over the same time.

Turning to inequality, the MTBPS document said that the share of total income going to the top 10% of local income earners is between 60% and 65%.

“Wealth inequality is even more pronounced,” the document said.

Gigaba said that local wealth remained highly concentrated with 95% of local wealth in the hands of 10% of the population.

The fiscal path the budget statement presents clearly cannot be sustained

by Lesiba Mothata

Mothata is executive chief economist at Alexander Forbes Investments.

October 25, 2017

Without well-considered reform in the political construct at the December ANC electoral conference, the stakes have risen for a profoundly negative economic scenario

For the first time since 1994, there is task team set up to deal with the fiscal challenges facing SA. It is led by the minister of finance who will report to President Jacob Zuma. The goal of this focused and select team is to come up with the actions needed to restore the sustainability of fiscal policy, and which will be put forward in the February 2018 budget.

Revenue shortfall

For the first time since the 2009 global financial crisis, there is an under-collection of R50.8bn, which was bigger than the market consensus of R40bn. All categories of tax revenue disappointed, with a material decline in personal income tax and value added tax (VAT). With weak growth and rising unemployment persisting in SA, the outlook remains challenging on tax collections.

For the first time since the budget expenditure ceiling was introduced in the 2014 fiscal year, it has been breached, to the tune of R3.9bn, mainly as a result of bailouts for South African Airways (SAA) and the South African Post Office (Sapo). This will be viewed negatively by ratings agencies.

The evidence of fiscal consolidation was expressed by maintaining the ceiling. However, breaching it indicates a lack of discipline on the expenditure side, with spending growing at a pace of more than 7% year on year. It is proposed that National Health Insurance (NHI), a new expenditure item, be financed through adjustments to medical tax credit.

Wage bill

Compensation to public-service workers has grown more quickly than the overall budget over the past eight years, and accounted for 35% of consolidated expenditure in 2016-17, up from 33% in 2008-09. Although detail on the public-sector headcount was provided, it did not reflect the promise of consolidation introduced by previous ministers of finance.

Debt load

There is a projected slippage in the gross debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio over the medium term, of a full six percentage points (see graph). To stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio below 60%, the Treasury has said that for the next decade, substantial tax hikes are needed. In the 2018-19 financial year, tax hikes of up to R40bn will need to be collected.

Debt-service costs remain the fastest-growing category of expenditure. In the next five years, 15% of main budget revenue will be spent servicing debt. This will prove to be SA’s Achilles heel. At these levels, the significant risk of debt sustainability begins to surface, especially when the primary balance (the difference between total revenue and noninterest expenditure) — which was expected to be positive over the forecast horizon in the February budget — has nosedived into negative territory.

Rating downgrades

This MTBPS has increased the likelihood of additional credit-rating downgrades before the year closes and ahead of the ANC electoral conference. Substantial fiscal policy uncertainty has been introduced by the weak economic growth outlook, altered budgeting process and deteriorating debt position.

Crisis or not?

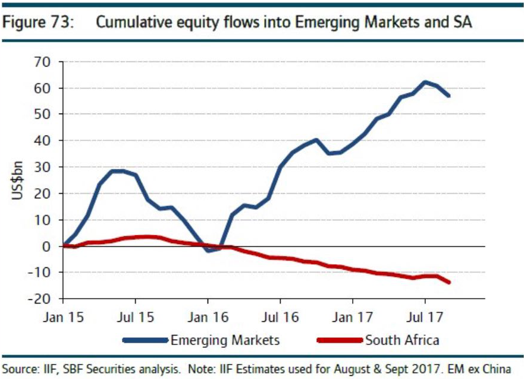

There is a notable and material deterioration in SA’s fiscal position, which will result in the 90% of debt issued in rand being downgraded to noninvestment grade, with potential capital outflows ensuing as a consequence. This has now become a base-case scenario with possible negative consequences for the rand, lofty equity markets, bonds and economic growth as a whole.

While these outcomes are undoubtedly dire, they do not represent a classical emerging-market crisis scenario, as observed elsewhere in history. The fact that SA still has fiscal policy levers to pull (VAT and corporate tax), an independent central bank, a solid and well-capitalized banking system and a cheap currency, provides comfort that the country can weather this storm. It can be argued that the markets, for some time now, have begun pricing in an outcome where SA is assigned a credit quality rating of noninvestment grade in local currency.

Clearly the fiscal path presented in this medium-term budget policy statement cannot be sustained. Much of the required changes need different political input. Without well-considered reform in the political construct at the December ANC electoral conference, the stakes have risen for a profoundly negative economic scenario, which will adversely affect the financial well-being of all South Africans.

It is during times such as these that a risk-led investment strategy is needed. Economies go through cycles, influenced by global factors and domestic political outcomes. During an investor’s journey, there will be periods of bounty and those punctuated by bumps. Much of what could ensue in SA’s markets and its economy will be categorized by heightened volatility.

Through all these cycles, there is a need to have a very clear objective in investments — and to stay the course for the long-term.

Economic Analysis

by Dwaine van Vuuren

Dwaine van Vuuren has a BSc(Hons) degree majoring in Computer Science and is a full-time trader, global investor and stock-market researcher. His passion for numbers and keen research and analytic ability has helped make his research sought after.

Annual GDP Growth

This is not just a snapshot of a once-off problem. It’s a clear and persistent decoupling of SA to the global and emerging market economies, as shown below:

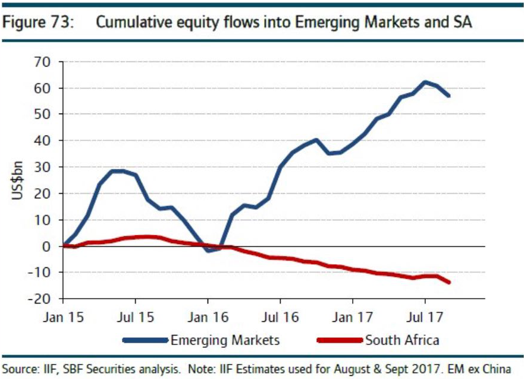

SA’s decoupling from the global economic boom (you know we are in one, right?) is most aptly represented when one looks at Emerging Market inflows, which are projected to reach $1 Trillion in 2017. The money is flowing into growing developing markets of which SA is clearly not qualifying due to lack of growth. And here is the direct cost of the mismanagement of our economy:

Fiscal authorities at the Treasury have performed an honest assessment of the fiscal matrix in the medium-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) and painted a worrisome picture. Contrary to the previous budget formulation processes, what came out of this MTBPS was only a diagnosis of the problems, and the fiscal hole was quantified.

The medium-term budget did not indicate how these issues would be solved. Instead, all potential actions and resolutions have been deferred to the presidential task team on fiscal policy, with an expected delivery on the outcomes in the February 2018 budget.

This represent a fundamental shift away from the budgeting framework SA has been accustomed to since 1994, and it will have negative consequences for how markets react — including potential credit-ratings downgrades.

Cumulative equity flows into Emerging Markets vs South Africa

It’s not rocket science what needs to be done to fix the economy and hence our horrendous unemployment. It’s all been talked about, debated and agreed. Even policy documents have spelled out what needs doing. But for some reason we seem stuck in a state of paralysis, making no progress at all. It’s a crying shame that we are not capitalizing on a global economic recovery windfall to redress our sorry state of affairs. We’re long on talk, late on strategy and woefully short on execution.