Is the Reconciliation of Turkey and Israel Viable?

In one day Turkey announced reconciliation with both Russia and Israel. See Huffington Post “Turkey Moves To Restore Relations With Russia And Israel On The Same Day”, June 2016.

Obviously this reconciliation is closely related to cooperation of these three countries in the natural gas sector. In order to assess the viability of the reconciliation between Turkey and Israel one definitely needs to examine the prospects of their cooperation in the natural gas market.

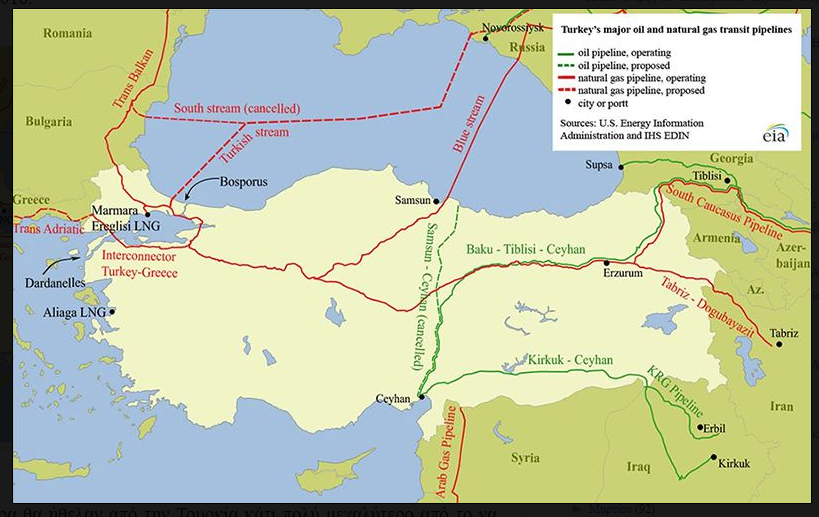

The first thing that we know is that Turkey wants to buy natural gas from Israel’s largest gas field Leviathan, in order to obtain access to cheap natural gas for Southern Turkey. An Israeli-Turkish pipeline would provide Southern Turkey with much cheaper gas, when compared to natural gas from Russia, Azerbaijan, Iraq and Iran, and it would also avoid Kurdistan.

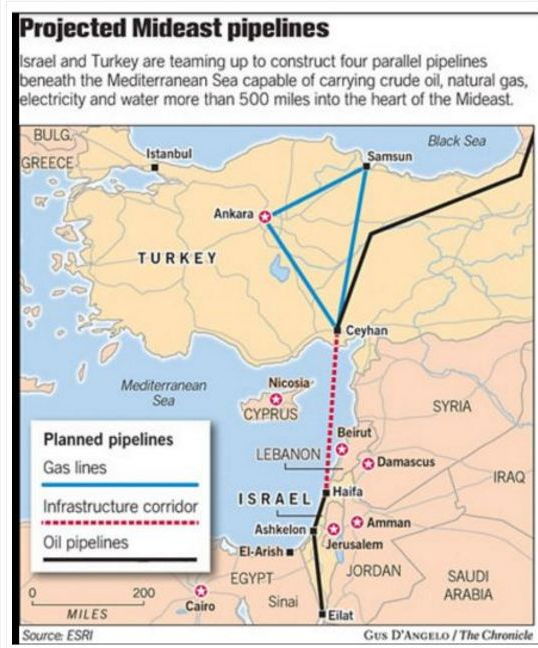

Map 1 Turkey – Natural Gas

The other thing that we know is that in August 2015 the largest natural gas field of the East Mediterranean Sea was discovered in Egypt i.e. the Zohr field, and therefore the plan of Israel and Russia of jointly exporting natural gas to Egypt was no longer viable in the long run. Turkey was the only other country of the East Mediterranean Sea that could absorb large quantities of natural gas. Lebanon, Cyprus and Greece consume very small quantities of natural gas.

A long time ago Turkey proposed Israel to buy natural gas from Leviathan, in a “strictly business” agreement, without the two countries becoming friends again. Israel had natural gas to sell, Turkey wanted to buy natural gas for Southern Turkey, and that’s what it takes for a deal.

Israel would have accepted, but there was a problem. The problem was that Israel would then go to a war with Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon, and Hezbollah would not only be supported by Iran, but also from Russia. That’s why Israel was not willing to enter this kind of agreement with Turkey.

But recently Russia changed her stance about a Turkish-Israel reconciliation. See Haaretz “In Change of Direction, Russia Welcomes Israel-Turkey Reconciliation Talks”, June 2016.

The explanation is that either Turkey accepted to buy natural gas from Israel even if Gazprom had a stake in Leviathan, or Turkey and Russia had reached an agreement about the new Russian-Turkish natural gas pipeline i.e. the Turk Stream, and in return Russia allowed Israel to sell natural gas to Turkey.

Note that the Turk Stream does not have to be the large Turk Stream with the 4 legs and the 63 billion cubic meters of gas per year. It can be a smaller Turk Stream with 2 legs and 30 billion cubic meters, or even a smaller one with 15 billion c.m, like the Blue Stream pipeline.

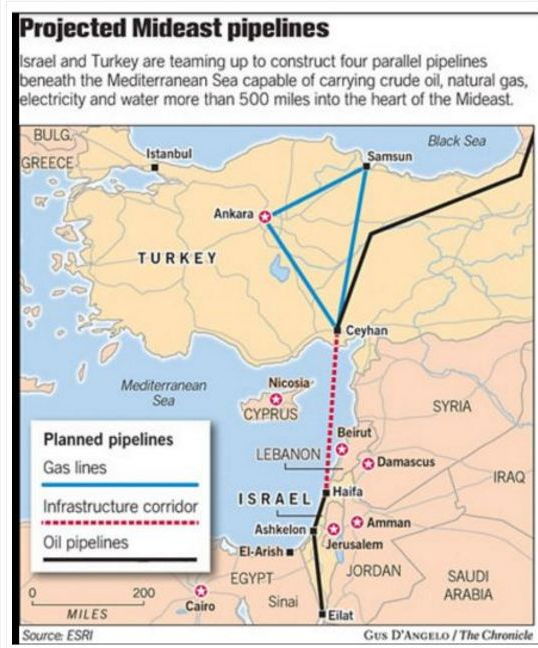

Map 2

What is important is that for some reason Russia accepted the establishment of Turkish-Israeli diplomatic relations.

The question that arises is whether this reconciliation between Turkey and Israel is viable. According to the Foreign Affairs magazine it is not very viable, and it is very likely that problems between Turkey and Israel will appear soon. See Foreign Affaris “Terrorism and Turkey's Deal with Israel”, June 2016.

According to Foreign Affairs, when there will be a new war in Gaza, and sooner or later there will be one, Erdogan will have to recall his ambassador from Israel. The article also mentions the pressure the Egyptian socialists put on Israel in order to adopt a tougher stance for Turkey in Gaza.

What the Foreign Affairs is trying to say is that Hamas in Gaza is also supported financially by Qatar and militarily by Iran, and if Iran, or Qatar, causes a new war with Israel, Erdogan will be in a very difficult position, since he wants to be the leader of the Muslim World. Therefore he will have to recall his ambassador from Israel, and become very aggressive towards Israel, and that will cause a new collapse in the relations between the two countries.

What the Foreign Affairs say really makes sense. But remember that if in the meantime an agreement is signed between Turkey, Israel and Russia for Leviathan, the Israeli gas will flow to Turkey, even if Turkey and Israel become enemies again. This is a mutually beneficial agreement, and the problem for closing the deal was not that Turkey and Israel were enemies, but that Russia would not allow it. Now that Russia allows the deal to go ahead, for whatever reasons, Turkey and Israel can close the deal, even if there is a very high chance of the two countries becoming enemies again.

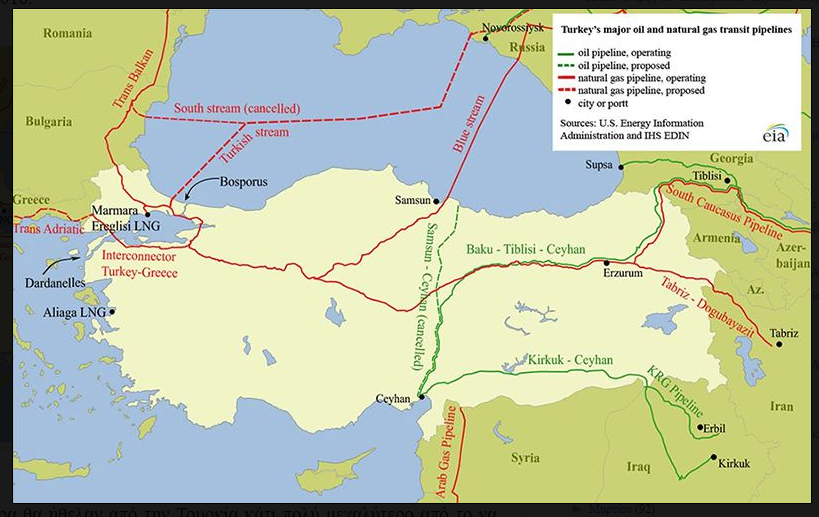

Remember that what Erdgoan really wants is to form a Muslim oil and natural gas cartel, which will be sponsored and protected by Turkey. That’s why Erdogan wants Shias and Sunnis to be united, and the same for the Arabs, the Persians and the Turks. If Qatar and Iran reach an agreement they can send their gas to Turkey, and Turkey can send it to Europe. Erdogan wants to be the leader of the Muslim World against the “crusaders”, something that hurts Turkey’s relations with the West, but it increases Erdogan’s prestige in the Muslim World. See “Pan-Arabism VS Pan-Islamism”.

https://iakal.wordpress.com/2016/05/21/pan-arabism-vs-pan-islamism/

Therefore the Foreign Affairs article definitely has a point. Remember that the Iranians are Shia Muslims, and Shia Muslims are only 10-20% of the global Muslim population, while Sunni Muslims are 80-90%. Therefore the war on Israel has traditionally been the ace in Iran’s sleeve, when trying to gain influence in the Muslim world against Saudi Arabia, which was an American ally, and Turkey, when the Turkish Kemalists were Israel’s allies. If Erdogan wants to be the leader of the Muslim World it cannot afford to be a friend of Israel while Iran supports a holy war against the Jews. He will have to follow Iran’s aggression on Israel. And that’s what the Foreign Affairs article really means.

And I agree 100% with the Foreign Affairs, except for one thing. There is the issue of the Russia-Turkey-Israel pipeline that was discussed in 2006, and which was abandoned when the Leviathan gas field was discovered in 2010, and the relations between Turkey and Israel collapsed.

Map Russia-Turkey-Israel Pipeline

If such a pipeline is constructed, then Turkey and Israel can send Russian natural gas to Asia, becoming natural gas hubs, through the Ashkelon-Eilat pipeline in Israel, and an LNG terminal in the Israeli Eilat port in the Red Sea.

Map

Remember that India wants to import 30 billion of Russian natural gas per year. See “India may import Russian gas via Iran swap or TAPI pipeline”, December 2015.

India is a traditional Russian ally, but Russia is upset due to the warming in the American-Indian relations. India and the US are forming an alliance against China. India wants to import natural gas avoiding Pakistan, her main enemy, and Iran is discussing the possibility of sending gas to India through Oman, and an underwater natural gas pipeline which will bypass Pakistan.

An alternative would be for India to import gas from the East Mediterranean Sea. Israel and Egypt jointly have 3 trillion cubic meters of gas reserves, nothing when compared to the 48 trillion of Russian gas, or the 33 trillion of Iranian gas, or even compared to the 25 trillion of Qatari gas. But if the Russian gas was to reach East Mediterranean Sea, through Turkey, and then the Red Sea through Israel, it could be liquiefied at Eilat port and sent to India, or other countries of Asia.

Russia could send her gas to India throuth the TAPI pipeline (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India), if it could pass from the turbulent Afghanistan and the Taliban terroirsts. But then again Pakistan would be involved and India would not be happy.

Or Russia could send her gas to India through Azerbaijan and Iran, but Azerbaijan and Iran are Russia’s rivals in the gas market. On the other hand Turkey and Israel are not Russian rivals in the natural gas markets, because they are very poor in natural gas reserves, at least when compared to Russia.

Also remember that Israel and India are allies against Pakistan. Turkey’s relations with India are problematic, due to Turkey’s traditional support for Pakistan, but from 2013 the Turkish-Indian relations were improved, when India promised Turkey to construct oil refineries in Turkey, and jointly exploit the gas and oil fields of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan in the Caspian Sea. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are Turkic countries and have very good relations with Turkey, even though they are also influenced by Russia, since they were members of the Soviet Union. See “India’s Turkish opportunity”, November 2015.

See also “India and Turkey: Friends Again?”, July 2013.

Also remember that Egypt has very good relations with Russia. Moreover Saudi Arabia is not very interested in natural gas, because she is not as rich as Iran, Russia and Qatar in natural gas. Saudi Arabia domestically consumers the natural gas she produces. Saudi Arabia is interested about her oil exports, but Russia mainly exports oil to Europe, while Saudi Arabia mainly exports oil to Asia. For Saudi Arabia it is a lot more important that Turkey does not support the Muslim Brotherhood in Saudi Arabia, together with Qatar and Iran, or that Russia does not support Iran against Saudi Arabia. Remember that Russia and Saudi Arabia have agreed that Russia will construct in Saudi Arabia factories for the production of nuclear energy. I mean that Saudi Arabia would not be very disturbed if Russia, Turkey and Israel were to send natural gas to Asia. Iran and Qatar would be very upset.

Moreover the Red Sea seems quite safe for such a project, at least if Saudi Arabia was to allow it. Israel and Egypt would be involved in the project. Sudan, after being the strongest Iranian ally in Africa for decades, in 2015 change sides and allied with Saudi Arabia. Moreover Saudi Arabia will open a military base in Djibouti, and Eritrea is also a Saudi ally. Ethiopia has very good relations with Israel, and anyway Ethiopia does not have access to the Red Sea.

Map The Red Sea

There is of course the war in Yemen, where Iran is supporting the Shia Houthi rebels, and there is also the issue of Al Shabbab, the terrorist organization of Somali. Al Shabaab controls a large part of Somalia, and has been traditionally armed by Iran. See “Al Shabaab : The Strongest Terrorist Organization of East Africa”.

https://iakal.wordpress.com/2016/02/20/al-shabaab-the-strongest-terrorist-organization-of-east-africa-and-its-funding/

But remember than Turkey is preparing in Somalia her first military base in Africa. See the Daily Sabah “First Turkish military base in Africa to open in Somalia”, January 2016.

What I am saying is that I agree that there are many problems in the Turkish-Israeli rapprochement, and even though a cooperation of the two countries in Leviathan will be mutually beneficial it will not guarantee normalization. If only Leviathan is involved the relations between the two countries will probably collapse again.

But if Russia, Turkey and Israel do indeed decide to send Russian gas to Asia, then they will hurt vital Iranian and Qatari interests, and Turkey and Israel will have to cooperate a lot more closely against Iran, because Iran will start supporting terrorist attacks against both countries. This is more important for Turkey, because Iran is already doing it to Israel.

Map Turkey-Iran-Qatar

Therefore even though I find the Foreign Articles very to the point, I would like to wait and see what kind of deals will be reached by Russia, Turkey and Israel. Is it going to be just Leviathan and Turk Stream, or Asia will also be involved? I think it makes a difference.

Map

Articles

“Turkey Moves To Restore Relations With Russia And Israel On The Same Day”, June 2016

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/turkey-russia-israel-relations_us_57716029e4b017b379f6b5cd?&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=World+Post+062716&utm_content=World+Post+062716+CID_ba287544e704ce98dc38115b8ef7eacf&utm_source=Email+marketing+software

“In Change of Direction, Russia Welcomes Israel-Turkey Reconciliation Talks”, June 2016

http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.723675

“Terrorism and Turkey's Deal with Israel”, June 2016

On Tuesday, three machine gun-wielding suicide bombers attacked Istanbul’s Atatürk Airport, killing 41 and injuring hundreds. News of the attack quickly overshadowed the week’s other major development in the country: a deal to normalize relations between Turkey and Israel after a six-year falling out. Although the two events might seem unrelated, they are connected in that one of the major factors driving reconciliation was cooperation on intelligence and counter-terrorism. Whether the deal will survive long enough for such benefits to be realized is a question that only becomes more urgent after the horrific terrorist attack.

Israel and Turkey’s announcement that they had agreed on the terms of their reconciliation came after years of false starts. Under the deal, Israel will pay Turkey $20 million in compensation for the nine Turkish citizens killed during the raid on the Mavi Marmara flotilla in 2010, allow Turkey to send humanitarian supplies to Gaza via the Israeli port city of Ashdod, and permit Turkey to support building projects in Gaza, including a hospital, power plant, and desalination plant. In return, Turkey has promised to end the lawsuits still pending in its courts against four high-ranking Israeli military officials involved in the flotilla raid, stop Hamas from launching or financing terrorist operations against Israel from Turkish territory, and intercede with Hamas on Israel’s behalf to secure the return to Israel of two Israeli civilians and the bodies of two Israeli soldiers being held in Gaza. Both sides have also agreed to return their ambassadors to the other country and to drop any remaining sanctions against each other.

On paper, this all sounds great, and there is no question that reconciliation can theoretically help both sides. The drivers of past aborted attempts at normalization, namely potential energy cooperation and coordination onSyria and counter-terrorism, are still at work, and there are benefits for both sides to be realized. Nonetheless, the celebrations in Jerusalem and Ankara are more likely than not to be short-lived for two reasons: the parameters of the deal may be more difficult to abide by than appears at first glance, and the entire structure could well fall apart at the first sign of the inevitable next round of fighting in Gaza.

Because Israel formally apologized to Turkey in March 2013 and only now has to now transfer the money for compensation, its side of the bargain is unlikely to face many hurdles, particularly after Israel’s security cabinet on Wednesday voted seven to three in favor of the deal. Israel had already offered to facilitate the passage of Turkish humanitarian supplies to Gaza through Ashdod subject to Israeli inspection, and so, although snags may occur, Israel’s commitments under the agreement are relatively straightforward.

Turkey’s commitments to Israel, however, are bound to run up against the limits of Turkish domestic politics andTurkey’s regional influence. For example, Ankara has repeatedly requested that its courts drop the lawsuits against Israeli officers. The courts have refused because the families of those aboard the Mavi Marmara and the IHH—the group that organized the flotilla and that has been accused of having ties to al Qaeda—have refused to drop them. The Turkish government has no standing in the case. To get around that problem, Turkey intends to simply pass legislation invalidating any current lawsuits against IDF officers and soldiers stemming from the flotilla. Although this is a creative solution, it is bound to be enormously controversial in Turkey, where the victims’ families and the IHH both have massive public support. In fact, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is already taking fire over the accord in Turkey, where #IsrailinDostuErdoğan (Erdoğan, friend of Israel) has been trending on Twitter, and not in a complimentary way. Although Erdogan tends to get what he wants, the public outcry may make passage of the legislation in the Grand National Assembly less automatic than other presidential priorities.

Even thornier will be fulfilling the parts of the deal pertaining to Hamas. Turkey held the line on expelling Hamas from Turkey altogether (something Israel wanted). The negotiators instead promised to rein in Hamas’ activity, but how its efforts will be monitored or enforced is anyone’s guess. Should there be terrorist attacks inIsrael that Jerusalem suspects were planned and executed from Istanbul, Turkey will be hard pressed to definitively prove that Israel is mistaken. Further, with Erdogan having cultivated a close relationship with Hamas chief Khaled Meshaal for the better part of a decade, it is doubtful that the Turkish president will be more inclined to be harsh with Hamas than to maintain plausible deniability in the face of any evidence about Hamas attacks emanating from Turkish territory. Finally, Turkey’s pledge to pressure Hamas into returning the Israeli civilians and bodies of the soldiers is based on a calculation that Hamas’ political wing, with which Turkey has influence, is the ultimate arbiter of this issue, rather than its military wing, which tends to operate according to its own whims. That seems like a risky bet.

Even if Turkey is able to fulfill its promises regarding Hamas activity, the deal still has a fatal flaw: it depends on continued quiet in Gaza, which is a long shot. The two years of quiet since Operation Protective Edge enabled this deal, but conditions in Gaza have not improved since the last round of fighting, and, in recent times, fighting has broken out every two years. That neither side is eager to rejoin the battle may not matter; the last Gaza war, which lasted 50 days in the summer of 2014, was one that neither Israel nor Hamas appeared to want but were unable to stop.

Although no one can predict with certainty when another war in Gaza will break out, another round of fighting seems inevitable, and with it will come the end of the current Israeli-Turkish detente. The Turkish public still has low opinions of Israel, and Erdogan will be forced to recall his ambassador at the first sign of Palestinian civilian casualties, not to mention what will happen if any nascent Turkish building projects are struck by Israeli fire. Israel, meanwhile, would be hard pressed to retain normal relations with Turkey once Erdogan began his instinctual verbal broadsides against Israel, which in the past have included comparing Israel to Hitler and calling Zionism a crime against humanity. Turkish-Israeli rapprochement, in short, is resting on a house of cards that will be easily blown over at the first sign of Israeli-Palestinian trouble.

And even before fighting breaks out, Egypt will put pressure on Israel to back away from closer relations withTurkey given the current tensions between Cairo and Ankara. If there is one regional ally that Israel will go out of its way not to antagonize, it is Egypt. That Turkey will now be launching construction projects in Gaza is bound to cause even more friction between Erdogan and the Abdel Fattah el-Sisi government, which wants to limit Turkish influence in Gaza and also wants to avoid opening any escape hatch for Hamas. Egypt will no doubt make its displeasure known to Israel. Although such an eventuality did not prevent the deal from being finalized,Egypt’s ability to play spoiler should not be discounted.

Normalization of ties between Israel and Turkey is a good thing, but expectations should be kept in check. It is unlikely that the rapprochement will play out the way both sides intend, and it may not be too long before we are once again talking about how to get Israel and Turkey back together. The Istanbul terrorist attack only reinforces that renewed ties between the two is more important than ever, and it will be up to both governments to keep this in mind each time events inevitably transpire that subject closer relations to a renewed rupture.

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/turkey/2016-06-29/terrorism-and-turkeys-deal-israel?cid=nlc-fatoday-20160630&sp_mid=51728956&sp_rid=aWFrb3ZvczEwMDBAeWFob28uZ3IS1&spMailingID=51728956&spUserID=MTA3MTc0NjI3NDAxS0&spJobID=944339509&spReportId=OTQ0MzM5NTA5S0

“Turkey, Israel to build Mediterranean pipeline / 4 legs would carry crude oil, electricity, natural gas and water”, April 2006

http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Turkey-Israel-to-build-Mediterranean-pipeline-2498862.php

“India may import Russian gas via Iran swap or TAPI pipeline”, December 2015

1st, 2nd Paragraphs

India has proposed to import up to 30 billion cubic meters of gas a year from Russia either via swap with Iran or through the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan- Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, Russian Deputy Energy Minister Yury Sentyurin told Interfax.

He said the proposals were made last month at a meeting of a working group that is studying the feasibility of a Russia-India hydrocarbon pipeline system.

http://rbth.com/news/2015/12/04/india-may-import-rusian-gas-via-iran-swap-or-tapi-pipeline_547593

“Russia and the TAPI Pipeline”, December 2015

1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th Paragraphs

On December 13, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India broke ground on the constructions of a new natural gas pipeline that will carry Turkmenistani gas eastward toward the other three partner countries (Tribuneindia.com, Tribune.com.pk, December 13; Timesca.com, December 14). The Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) pipeline project, in one form or another, has been on the books for twenty years, going back to an abortive effort by the Union Oil Company of California (Unocal) and the Taliban in 1995 to formulate it. Given its location and ability to alleviate many critical economic and energy problems in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, the TAPI pipeline has been the subject of enormous geopolitical rivalry and maneuvering throughout this period (see EDM, December 14, 2010; February 16, 2011).

Inasmuch as this pipeline has received steady political support from the United State because it would enable Turkmenistan to find another alternative to dependence on Russia for exporting its gas, Russia has been very skeptical about the project (“Central Asia, Afghanistan and the New Silk Road Conference Report,” The Jamestown Foundation, November 14, 2011). Yet, in mid-2010, Moscow cautiously came around to ostensibly support as well as promise to cooperate with the founding members on the TAPI project (Central Asia Newswire, October 25). But even then its offer was insufficient. Although Moscow apparently put forward four different possible frameworks for its participation, Ashgabat refused them all (Eurodialogue.eu, November 17, 2010). As a result, Russia is now promoting various alternatives to the TAPI pipeline. These new proposals are clearly aligned with recent developments in Russian foreign policy, specifically efforts to retain India’s friendship and support while increasingly reaching out to Pakistan. In particular, Moscow is offering the two traditional main weapons of its foreign policy—i.e., energy and arms sales.

Consequently, in September 2015, Russia proposed building a South–North natural gas pipeline in Pakistan. This Russian pipeline would extend almost 1,100 kilometers, from the port of Karachi northward to Lahore, and carry Iranian gas shipped to Pakistan across the Arabian Sea via liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers. The entire scheme would reportedly be based on swaps between Iran and Russia for the original gas (Peq.com.pk, December 2; Russia-insider.com, September 9). As such, however, this project directly contradicts the entire logic of the TAPI pipeline as well as the US strategic objective of blocking both Iran and Russia from dominating energy flows to South Asia. At the same time, Moscow is discussing with New Delhi the possibility of exporting 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) a year of gas to India through Iran by means of a swap or, alternatively, by transporting it via the TAPI pipeline (Russia Beyond the Headlines, December 4).

Thus, characteristically, Moscow is attempting to have its cake and eat it at the same time by entertaining simultaneous proposals to send gas through the TAPI pipeline or to circumvent it and thus minimize its potential. Undoubtedly, Moscow realizes that while the pipeline is now formally under construction, completion and operation are by no means certain since there are major questions connected with securing enough financing for it. And ensuring a stable and secure environment in Afghanistan also remains an issue of concern. Therefore, from Moscow’s standpoint, it is equally if not more useful to have an alternative ready to offer that would increase Russia’s influence in Pakistan as well as maintain its position in India. Especially in view of the urgent energy needs of both India and Pakistan and Moscow’s abiding desire to retain as much leverage as possible over Turkmenistan’s gas, this policy makes excellent sense for Russia, even if it directly contradicts both Turkmenistani and US interests and policies.

http://www.jamestown.org/regions/s