Introduction

Surveys and indices suggest that as many as 20 to 30 percent of states today are deeply vulnerable to armed domestic conflict.1 Such countries are a constant threat to international peace and security-a reality recognized in the top-level priorities at the United Nations, by the National Security Strategy of the United States, and around the world.2

Responsive to this threat,3 the number and quality of broadly comparative, quantitative approaches to understanding-and possibly anticipating-such conflict have expanded. Quantitative approaches have been used to track the frequency of armed conflict, its intensity, patterns of termination, and consequences. With respect to anticipating conflict, quantitative research that compares countries globally or regionally on a dizzying array of hypothesized conflict related variables allows us to evaluate the association of possible underlying vulnerabilities to violence. This research has been particularly important in understanding that conflict propensity is deeply and directly associated with state fragility and that weak states are promising settings for insurgent and nonstate militias to emerge.4

Uncertainty about future conflict remains high. Studies show that the overall frequency of armed conflict is down since 1992, following an initial spike at the end of the Cold War. Paradoxically, however, the underlying vulnerabilities may be worsening globally, particularly in the context of repeated economic shocks and climate change.5 The past thus may not predict the future in terms of trends in armed conflict.

This paper provides a bird's eye view-a meta-analysis-that compares various quantitative measures of vulnerability to conflict. We seek to answer a question that has not been well addressed in this field: How do the principal quantitative measures of conflict vulnerability compare to one another? Other, related questions follow:

-

How do these projects suggest that their indices are similar to or different from others?

-

How do the measures actually correlate with each other?

-

What countries do the measures evaluate differently and why?

-

To what degree do the indices provide the same information as would one or a small set of key variables?

Comparing Approaches to Conflict Vulnerability

We are not the first to undertake such comparison. In a conceptually groundbreaking review for the Council on Foreign Relations, Monty Marshall found that models for anticipating conflict generally fall into three categories.6 First, the academic community has since the 1960s developed conditional and causal factor models, looking theoretically or with qualitative analysis to a focused driver or a small set of drivers and attentive to civil war (often associated with poverty and inequality), greed and grievance models of rebellion, and ethno national and revolutionary civil war. Second are predictive models, in which theoretical foundation and significant empirical research is directed at developing parsimonious explanatory systems. The work of the Political Instability Task Force (PITF) is prominent here. Finally, general risk and capacity models look to drivers that indicate ability to manage conflict over a relatively long period, and seek to identify the likelihood that a state will experience conflict, rather than to predict when instability might appear.

Marshall identified four measures in particular in this third category: the Failed and Fragile States Index of the Country Indicators for Foreign Policy (CIPF) system at Carleton University, the Failed States Index (FSI) developed by Pauline Baker and used by the Fund for Peace, the State Fragility Index (SFI) originally developed by the IRIS Center at the University of Maryland and carried by Marshall to George Mason, and the Index of State Weakness (ISW) project by Susan Rice and Stewart Patrick for the Brookings Institution.7 Marshall found high correlations across these measures, suggesting that analysts mostly agree about what they are measuring and how to measure it.

In a report for the German Development Institute and the United Nations Development Program, ]avier Mata and Sebastian Ziaja conducted an extensive and more technical analysis of eleven measures of fragility.8 These included the four measures that Marshall identified as general risk and capacity models, and that are central also to our analysis in this report. Of their remaining seven measures, we also look here at two: the University of Maryland's Peace and Conflict Instability Ledger (CIL) and the Economist Intelligence Unit's Political Instability Index.

We considered three others Mata and Ziaja examined, but do not include them here because they focus on either issue or geography: the World Bank's International Development Association Resource Allocation Index (IRAI), the Global Peace Index, and the World Peace Foundation Index of African Governance, which was initially sponsored by the Ibrahim Foundation. Mata and Ziaja also reviewed the Bertelsmann Transformation Index of State Weakness Index and the World Bank's World Governance Indicator measure of political stability and the absence of violence.

The Mata and Ziaja analysis provides a useful review of the features of each measure. It also covers a great deal of ground: a set of standard descriptions (relevancy, quantification, accessibility, transparency, multi country coverage, and information updating); validity and reliability issues; source of data (including the degree to which projects use standard quantitative measures or expert assessments and the extent of data overlap across projects); the institutional home (academic, think tank, media); the variable and mixed use of index values, rankings, and categorizations; and approaches to visualization. The report looked at the intercorrelations of measures as well as at the degree of similarity in the ranking of the ten most fragile states. As our analysis does, it noted that most indices look at fragility in four dimensions: social, political, economic, and security.9

In a volume devoted primarily to considerations of their own CIPF measure, David Carment, Stewart Prest, and Yiagadeesen Samy reviewed the relationships between it and the George Mason State Fragility Index, the Fund for Peace's Failed State Index, the Brookings Index of State Weakness, and the World Bank's low-income country under stress (LICUS) analysis measure-the Country Policy and International Assessment (CPIA) index.10 The review also found high correlations across the measures11 and close relationships between them and several measures of development, including the log of GDP per capita and an inverted-U relationship with democracy level. The volume includes a useful literature review situating the study of fragility within a variety of social-science traditions.

The IFs System

Building on these earlier efforts, the International Futures (IFs) modeling system provides a unique platform for extending such comparison. 12 The IFs project provides the capability to collect, scale, and compare multiple quantitative studies on various dimensions of international peace and conflict and to analyze their similarities and differences statistically. We undertake the analysis, which focuses on vulnerability to conflict, in two steps, qualitative and quantitative. First, we consider the various series and indicators available on their own terms. Second, we explore the relationships among the various series and indicators.

We situate our study in the context of the literature on drivers of conflict and theoretical approaches to vulnerability. This gives us a typology of vulnerable states to help guide subsequent analysis and interpret the results in relation to other findings. We then compare measures, using qualitative analysis, regression analysis, radial diagram presentation, and more general analysis to show how well, or how differently, some of the larger quantitative research projects compare.

Overall, our hope is that this meta-analysis approach will help those in scholarly and policy environments understand and evaluate more fully the various quantitative series on conflict vulnerabilities. We view this project as an important step toward the IFs project's goal of better forecasting the potential for conflict, thereby ameliorating or even avoiding it.

Conceptual Orientations and Approach

Before comparing measures of vulnerability to conflict, it is critical to define key terms and ideas.

What Is Vulnerability?

The CIFP project focuses on failed and fragile states, presenting a fragility index. The Fund for Peace measures state failure. The Brookings Institution project looks at state weakness. In our view, a concept that links each of these studies, and lends them to comparative analysis, is vulnerability to conflict. This in turn relates to broader approaches to understanding causal drivers, risk, crisis, and the outbreak of armed conflict or other consequences of failure, fragility, or weakness.13

Alternative theoretical orientations derived from the causes of conflict literature directly inform the content and measures of conflict vulnerability frameworks. The literature on underlying causes of conflict typically explores two central questions: What are the underlying causes of conflict in a society? What are the dynamics, and therefore also the agency, that precipitate or accelerate the escalation of violence? Such causal analysis is an essential first step in preventing conflict, for example, as the backdrop to the more contingent stories about why and how a conflict escalates in any particular setting.14

The focus on the first question is critical. Most conflict assessment models first posit background conditions (drivers) of internal conflict as a set of preconditions that fuel escalation when a moment of crisis occurs.15 In our analysis here, we are interested in evaluating the research on conflict vulnerability in terms of leading theoretical orientations in the field of causes-of-conflict analysis. William Zartman, for example, argues that any single factor or exclusive theory of internal conflict, such as isolating greed (economics) or grievance (social psychological) determinants is "profoundly uninteresting"; instead, the intersection of need, creed, and greed offers the best hope for uncovering causal relationships.16 We need, in fact, to look still more broadly and to the interactions among putative root causes.

Vulnerability as a Spectrum

Conceptualizations of vulnerability may directly affect how the research projects we are comparing see any given country.17 Vulnerability to conflict is a spectrum, from fully collapsed or mostly failed states to stable ones.18 India, for example, does not routinely appear on the global lists of fragile states, and certainly not on those of failed states, but certain regions of India– such as Kashmir and some northeastern areas-do experience insurgencies, displacement, and high levels of militarization. Thus, it does appear in common measures of "conflict-affected states, "for example in the work of the Uppsala Conflict Data Program.19

Three states appear routinely at the top of fragility lists: Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Somalia. These countries are characterized by chronic, decades-long conflict during which the state has either collapsed or failed and the international community's state-building efforts have yielded little return. They typify conflict-induced humanitarian emergency. Although all have a putative central government (even Somalia), most do not demonstrate enough authority, capacity, or legitimacy to minimally control their own territory or to provide basic services.

In a second tier are the commonly listed fragile or conflict-affected states, but identifying and ranking them along the spectrum gives rise to considerable dissonance among analysts and observers.20 For example, a theoretical perspective that emphasizes regime repression may rank a country like North Korea as particularly vulnerable to violence, whereas one that emphasizes ethnic differences may see it as less so. Likewise, Colombia sometimes makes this list because of the degree of recent and ongoing conflict in that country, whereas measures that rely on either deep-driver socioeconomic indicators, such as GDP per capita, or proneness to state failure may exclude it. In our analysis, it does not make the list (see appendix 3). Because of both their high vulnerability and the differences in their treatment by various measures, countries on this range of the spectrum animate our analysis.

A typology of countries with red-level vulnerability may help delineate subcategories. For instance, within the annual World Bank list of fragile states, four categories of vulnerability to conflict are distinguishable:21

-

autocratic regimes characterized by repression and misrule-for example, North Korea, Myanmar, or Zimbabwe

-

weak states unable to address widespread or acute poverty, suffering, or social grievances-for example, Haiti or Chad

-

states with deep internal ethnic and sectarian differences-for example, BosniaHerzegovina or Iraq

-

states still in transition from previous conflicts or peacebuilding efforts-for example, Angola, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Liberia, Rwanda, or Sierra Leone22

In our assessment of how projects differ in the treatment of outlier countries (those for which vulnerability assessments differ), such a typology, might be useful. Other categories, however, would bring particular theoretical orientations-such as anocracies (mixed regimes) or recently changed governmental systems within a perspective focusing on regime type-to our attention. Like unhappy families for Tolstoy, fragile states tend to be fragile in unique ways,23 and typologies of subcategories can quickly become overwhelming.

The picture does not necessarily clarify when one considers the next tier, approximately seventy countries that show some but more limited vulnerability to conflict. These include, as mentioned, India and Colombia-middle-income countries that are generally higher capacity states but have acute subregional or protracted, localized conflicts. Additional examples include regions of China, Indonesia, Russia, and the Philippines, in which conflict is for the most part geographically isolated, and does not affect central state power or overall stability. Another example is Lebanon, where overall levels of economic development are middle income, with pockets of high levels of both wealth and poverty, and where internal dynamics remain tense and an escalation of violence is an ever-present possibility.

Also included in this category are other subcategories: states with problematic societal conditions (such as ethnic fragmentation, as in Ghana or Mexico, which often interacts with other drivers of conflict vulnerability such as competition for scarce productive land and pockets of extreme poverty); countries that may appear to have strong state capacity, but in which certain elements of vulnerability are significant (such as extreme income inequality in oil-exporting states); and autocratic regimes that may be vulnerable during moments of inevitable regime change (as in Belarus or-to take a recent example-Egypt). The imbroglio in Libya underscores that even these middle tier vulnerable countries are potentially vulnerable to state failure, given the right mix of external and internal precipitating conditions including factors such as primary commodity dependency.

Last is a group of about sixty countries-mostly the higher-income OECD states-in which vulnerability to internal armed conflict seems minimal. Even these states can be vulnerable to episodes of social violence, however, such as riots or violent protest or even moments of subnational state failure (as some have suggested occurred following Hurricane Katrina in the United States). And these countries may not be considered very peaceful when measured against a criterion such as participation in wars abroad.24 However, high levels of socioeconomic development, paired with significant state authority, capacity, and legitimacy, suggest that these countries are not at significant risk of internal armed conflict.

We are, of course, not the first to suggest a spectrum of classifications.25 In fact, the Brookings analysis similarly identifies the bottom three countries, labeling them failed states; it refers to the bottom quintile as critically weak states and to the second quintile as weak states. The Bertelsmann project names failed states, very fragile states, fragile states, and remaining countries not classified. Although the Fund for Peace uses quartiles, Foreign Policy assigns names to its ranking: critical (1-20); in danger (21-40), and borderline (41-60). As Mata and Ziaja point out, such fixed category borders can be problematic in longitudinal analysis: for example, a country can move across category boundaries without a change in its index value, simply because of changes in other countries. For this reason we prefer the notion of a spectrum.26

Drivers of Vulnerability

Research on the underlying vulnerabilities tends to isolate the central factors of social, economic, political, and security conditions that are common in countries affected by armed conflict and armed violence.27 Although attention to multiple and interactive effects makes much sense in the analysis of conflict, some literature has tended to try to identify leading or most salient variables. For instance, the work of Collier and his colleagues has emphasized economic variables, particularly the importance of natural resources that allow access to "lootable goods."28 Issues of natural resource management, especially of high-value commodities such as oil, access to employment, scarcity of water, food insecurity, lack of affordable and decent housing, or systematic economic discrimination-have all been seen as strong underlying drivers that have over time erupted into violent conflict.29

The social dimensions of vulnerability reflect a concern with the structure of society and the ways in which imbalances, discrimination, and the relationship between groups, economic opportunity, and the states interact.30 Leading theories today identify the overlap between social class deprivation and identity (particularly of marginalized minorities) as a critical and enduring cause of conflict. The state often exacerbates economic and social divisions, yielding political economy relationships of what are called horizontal inequalities. Thus ethnic fragmentation alone does not suggest vulnerability to conflict. Rather, such vulnerability normally reflects a history of ethnic enmity, transboundary ethnic ties, and ethnic discrimination or marginalization.

Several studies have evaluated the importance of demographic factors on conflict vulnerability,31 as has research that looks at migration as both a cause and consequence of conflict. Some social instability may also arise from rapid urbanization, in which deprivation in and around burgeoning developing world cities can create conditions of human insecurity.32

Denial of essential human needs is a critical, micro-level category of vulnerability. Countries at the bottom of the global rankings on human development also tend to be susceptible to conflict; thus a vicious cycle between underdevelopment and conflict is hypothesized. For example, today's most severe food security crises are in conflict-affected countries.33 Typically, measures of essential human needs and human development, such as the UNDP Human Development Index, indicate vulnerability to conflict, particularly components of these indices that most clearly suggest serious human suffering, such as infant or child mortality.

Governance matters for conflict vulnerability in two ways: state strength and regime type (or the character of governance). Indeed, it is the axis around which the vulnerabilities to conflict interact with the official and unofficial institutions and processes through which social conflict is to be managed. he type of regime is seen as a critical factor-the more repressive a regime, such as in authoritarian settings, the greater the likelihood that it will engage in conflict internally (for purposes of repression) or with other democratic states.34 Thus measures of vulnerability to conflict should incorporate variables such as the level of militarization and repression by a state. Critical in this regard is the analysis of the human rights performance of a state, in particular human rights violations: some indices, for example, include levels of extrajudicial killings as an indicator.

The relationships between governance, especially regime type, and vulnerability to conflict are not, however, monotonic. hat is, mixed regimes or partial democracies tend to be more vulnerable than either democracies or autocracies.35 One of the weaknesses of most of the measures that we review in the next section is that they tend to build in variables as if their contributions to vulnerability are always consistently increasing or decreasing.

Looking more broadly at the security environment, criminality, lawlessness, and threats of armed violence are also closely related to conflict vulnerability. Indeed, interest in evaluating the interaction among social violence, vulnerability to armed conflict, and actual occurrence of armed violence is increasing.36 For example, some researchers emphasize analysis of violence against women as an overall indicator of the state's propensity for involvement in violent conflict.37

Vulnerability to conflict can also arise from regional effects, such as tangible spillovers including rebel incursions, transborder migration, external minorities, or a phalange of conditions summarized as "regional conflict complexes."38 Transborder flows of resources, recruits, and small arms are also factors in regional vulnerabilities. Likewise, cross-border support for rebel forces by hostile neighboring governments has also been seen as a component of regional instabilities that affect vulnerability to violence, especially in southwestern Asia and in several subregions in Africa. One can divide the security-condition variables into human security from regime repression, security-related vulnerabilities from intrastate conditions, and regional and global security effects.

Many vulnerable countries are conflict recidivists. he risk of new conflict is very much a function of experience of internal conflict or civil war.39. These fragile and conflict affected

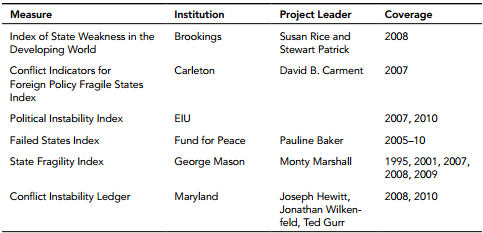

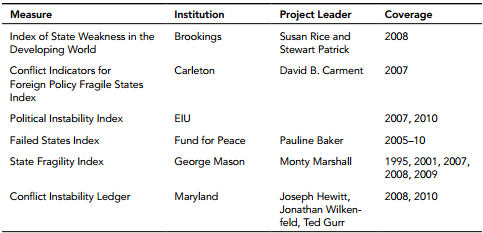

Table 1. Measures of Vulnerability to Domestic Conflict: Origins and Basic Information

Source: Authors' compilation

states appear chronically (at least for some) stuck in a vicious cycle of governance failures, development catastrophes, and self-perpetuating conflict dynamics.

Given this richness of potential causality concerning vulnerability to conflict, it is not surprising that measures will vary in the assessment of countries. We turn now to an analysis of that variation.

Measuring Vulnerability

his project is interested in quantitative, macro-level indexes that explore state vulnerability to domestic conflict. Regardless of the specific terminology of the measure, we have chosen indices to compare that meet the criteria that the measures clearly focus on vulnerability in a broad sense and are publicly available, current, and global in scope. hose criteria generated six indices. Table 1 lists the names of the measures along with their institutional affiliation, associated scholars, and dates of publications.

A variety of sources describe each of these projects, the most useful generally being their websites. The following publications directly address the indices:

-

Pauline Baker, Failed States Index (Washington, DC: Fund for Peace, 2009), www. fundforpeace.org

-

David Carment, "Country Ranking Table 2007," Country Indicators for Foreign Policy, www.careleton.ca/cifp/app/ffs_ranking.php

-

Joseph Hewitt, Jonathan Wilkenfeld, and Ted Robert Gurr, Peace and Conflict 2010 (College Park: Center for International Development and Conflict Management, University of Maryland)

-

Monty G. Marshall and Benjamin R. Cole, Global Report 2009: Conflict, Governance, and State Fragility (Vienna, VA: Center for Systemic Peace, George Mason University), www.systemicpeace.org/Global%20Report%202009%20Executive%20Summary.pdf

-

Susan Rice and Stewart Patrick, Index of State Weakness in the Developing World (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2008), www.brookings.edu/reports/2008/02_ weak_states_index.aspx

-

Economist Intelligence Unit, "Political Instability Index," ViewsWire, http://viewswire. eiu.com/site_info.asp?info_name=social_unreast_table&page=noads&rf=0

Most of the indices we considered but did not include had distinctly different conceptualizations of state vulnerability to conflict. For example, we omitted the Global Peace Index because it measured the presence or absence of domestic and international conflict associated with one country. Although external conflict sometimes does have a strong association with state weakness and failure, it is a different phenomenon. Because their focus is narrower, we did not include other measures, including some more closely related to governance quality; examples include the IDA Resource Allocation Index, the Freedom House Countries at the Crossroads measure, and the Bertelsmann Transformation Index. We also omitted the World Governance Indicator on Political Stability and the Absence of Violence, which reflects the level of instability more than the vulnerability to it. Finally, the Ibrahim Index of governance, which we also looked at in preliminary analysis, is both more specialized in issue focus and its geographic focus on Africa. In preliminary analysis, we explored correlations of such measures with each other and with the six measures examined here, finding that each evaluates or ranks countries quite differently from the ones that we chose and from each other.

We have chosen to compare six measures with four general methodological approaches. Our first approach is to look at them qualitatively. We begin the qualitative consideration by asking how the projects themselves define what they are measuring, their objectives, and their basic approach. We continue by identifying in four standard categories (social, economic, political, and security) the key variables, or at least groupings of them, that the measures tap. his should tell us much about what the projects believe they do similarly and differently.

Our second approach involves quantitative comparison of the measures across all 183 countries of the IFs system that provide values or ranks (using values whenever possible). That comparison has two elements. he first is simply intercorrelation of all measures with one another. The second is more sophisticated: we rescale all the measures to a common range and valence-higher positive values then indicating more vulnerability-and compare the generated values in both graphical and tabular forms. his approach provides considerable initial insight into how comparable the measures are. In this process, we also compare the measures to the average value across the indices for each of the 183 countries, fully understanding, of course, that the average is not necessarily better than any or all of the individual measures. The computation of that average, however, also allows us to say something about the spectrum of vulnerability to conflict we discussed earlier. We use the average evaluations to divide countries into four categories of vulnerability more systematically than the common arbitrary divisions by percentiles or even-numbered sets (such as the top twenty or top forty).

The third approach turns to specific countries. We identify countries about which the measures most agree and, especially, disagree. We use radial diagram presentation to help us explore the differences across measures for these countries. Although it is an interesting digression rather than a continued comparison across measures, in the subsection on specific countries we also look at the way in which the values defined by the spectrum analysis (associated with approach 2) compares to a series of important development indicators, including GDP per capita and the human development index (HDI). We also add a temporal element to that analysis, looking at how the evolution of those key variables relates to the contemporary categories of the spectrum.

The fourth approach turns back to corr