Death, Hope, Humor, Love and Sex*

When someone is in a social interaction, a complex set of emotions and feelings are being evoked on a moment to moment basis. That is, they are constantly changing rather quickly - from one second to the next to the next you could have many different emotions start, stop or occur simultaneously. However the level to which these emotions are recognized or felt is hard to figure out, it is not like people are taking account of all the second by second experiences of their feelings, or even if they can observe those consciously. I believe that the reality is that unconsciously these emotions are interacting with each other and influencing the conscious feelings and thoughts that you do have. They are still very important even though they aren't felt in an obvious way (which is why they are unconscious), however. The most powerful of these unconscious emotions I believe are the emotions of death, hope, humor, love - and sex (though sex is more of a simulation and humor more of an excitement).

Love is the most obvious example - even with someone you are love with the emotion love isn't present consciously every second you interact with that person, in fact, you probably only feel it very infrequently. That does not mean, however, that you are not in love with the person the rest of the time. Love is an unconscious factor in the relationship and in your emotions the rest of the time. Even though you don't really "feel" it, it has tainted your feelings more towards love, it influences your feelings to maybe be more powerful and in that direction. The same is true for the other emotions I mentioned, they are constantly present and influencing your emotions and feelings even though you wouldn't say you are feeling (for example pain (death) or hope).

I called death an emotion but really it only gives rise to the emotion pain or painful emotions. So hope must taint all your emotions in a positive way, make them more happy in a hopeful sort of way. Pain makes your emotions difficult and painful in a doomed sort of way, similar to the experience of death. When you interact with someone, if pain or difficulty is present you could say that death is a factor in the interaction. The emotions you are experiencing are actually larger and more significant than you notice. You only notice obvious, clear instances when you experience emotion. The reality is, however, that you are partially in pain and partially in pleasure the entire time of an interaction, the death factor and the hope factor are there all the time, only unconsciously.

In classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory, the death drive ("Todestrieb") is the drive towards death, self-destruction and the return to the inorganic: 'the hypothesis of a death instinct, the task of which is to lead organic life back into the inanimate state'.[] It was originally proposed by Sigmund Freud in 1920 in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, where in his first published reference to the term he wrote of the 'opposition between the ego or death instincts and the sexual or life instincts'.[] The death drive opposes Eros, the tendency toward survival, propagation, sex, and other creative, life-producing drives.

Frued believed in a death instinct (or drive), and a sex instinct. Freud encountered the phenomenon of repetition in (war) trauma. When Freud worked with people with trauma (particularly the trauma experienced by soldiers returning from World War I), he observed that subjects often tended to repeat or re-enact these traumatic experiences: 'dreams occurring in traumatic have the characteristic of repeatedly bringing the patient back into the situation of his accident', contrary to the expectations of the pleasure principle.

In Freudian psychology, the pleasure principle is the psychoanalytic concept describing people seeking pleasure and avoiding suffering (pain) in order to satisfy their biological and psychological needs.

I have my own ideas about the death and sex drives, and the pleasure principle of Freud. I believe that pain and pleasure are both necessary and present in many interactions, and therefore you could view it as there being a drive towards pain and a drive towards pleasure and sex. It is that simple, both pain and pleasure are always components in interaction, however they are so large and important that you could label them as instinctual and drives. They cannot be avoided - similar to how people can repeat traumatic experiences, even though it may seem like people only want pleasure, the reality is pain is just as natural and driven. People automatically cause themselves to experience pain - it is a part of life and your conscious and unconscious emotions.

Humor is also important. Life isn't just about doomful death feelings and motivations, or selfish pleasurable sex drives. There is hope and love, but those would be boring by themselves. People need to recognize that there is a lighter side to life, a fun and carefree excitement that is often found in humor. These emotions are all present in every interaction, they are balancing each other and interacting with each other all the time. Pain can balance pleasure, hope can change your expectations, sex can help you have "fun", and humor can cause you to think life is "fun" or "funny". How these emotions and feelings play out on a second to second basis is going to vary based on the interaction, but the point is they are all there all the time and are major conscious and unconscious elements.

What is Subtle About Social Interaction?*

If social interaction / psychology was straightforward, then life wouldn't be complicated and it wouldn't take 18 years of emotional development in order to become an "adult". How people socially interact develops and changes throughout their lives, so there must be very complicated factors present in social situations. People can deceive, play mind games, say completely appropriate or inappropriate things, act retarded or sophisticated, be friendly or isolated - and all of those things are just a few aspects of all the psychological factors involved in social interaction. There are many things to consider that play a role in interaction.

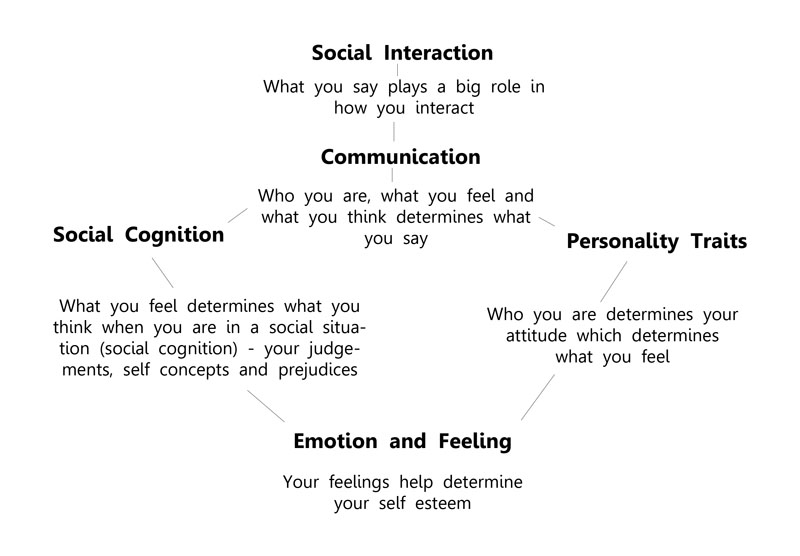

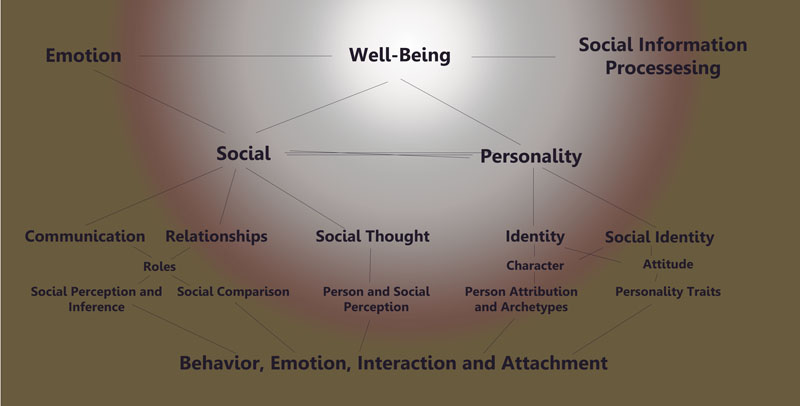

Emotion plays a role in interaction, people could be feeling one thing and presenting another emotion. Emotions determine how people feel which could change what they might say or act like. Judgements, prejudices, self-concepts and other thoughts play a role in what people are thinking and that influences behavior and the emotions that occur. What happened to the people involved leading up to the social interaction plays a role in how they are feeling and what they might say, what they did that day or the last week. Taking that further, their entire life history plays a role in who they are and what they have to talk about. Social interaction could be considered subtle and precise or it could be considered rather simple. Once a child can talk he can socially interact rather well fairly quickly. Animals and babies even know basic social skills, they know to greet people (friendly or hostile), they know the basic emotions involved and act in sophisticated ways. They can run when afraid, be happy and respond to positive input and affection, or even play simple games. Advanced social interaction could be considered much more complicated than that or not that much more complicated at all.

People generally act in a similar manner socially, the ways they behave are fairly simple to understand. People can act in a hostile or gentle manner, be excited or happy or sad and angry. There are different ways of thinking (based on who you are), and different ways of interacting with people. Everyone wishes to be liked, chosen or respected, but to achieve this, one must be 'visible'. Social visibility requires in turn the adoption of points of view which are original, and which are maintained with constancy and vigor. People have an image of themselves that they wish to present to others.

It is possible that people enter into relationships and associate with each other because they are similar (or think that they are). In this perspective, similarity is considered the foundation of social bonds. Individuals enter into relationships and association when they discover - or assume - that they have something in common and are similar, at least in some respects. Individuals will engage in behavior aiming to bring closer to them those with whom they are comparing themselves. It is those who are the most different who must make the required effort to get close to others. People might like other people with similar attitudes to themselves more so than people with attitudes which differ greater. There is a social desirability of personality traits and attitudes (those that are similar or not similar). In sum, similarity appears to be linked to interpersonal attraction only so far as the consequences of this relationship are psychologically rewarding. So people like to be different in order to differentiate themselves, but they are also attracted to others with similar attitudes and ways of thinking as themselves.

People are similar and different, in social situations, difference and similarity are sought simultaneously. This is so in behavior which has been referred to as the 'superior conformity of the self' (or the 'PIP effect"). (PIP from primus inter pares (first amongst peers or equals)) The self-image is thus central in the determination of behavior tending towards both differentiation and non-differentiation. Everyone is normally able to establish a cognitive discrimination between the self and others, and also among other people. Consequently, the search for identity is made through the assertion of difference and its recognition by others.

Character Traits

For instance, character traits are subtle because they are more related to social interaction and personal behavior than personality traits, because character traits are more related to the consistent attitudes and behaviors of a person than personality traits are. Character traits are complicated because it can be hard to understand the nature of a persons various character traits. Consider, for example, someone who presents him- or herself as a generous person. He or she may truly care about others and wish to share with them or alternatively may have learned that the appearance of generosity will gain approval from others and therefore help him or her to deny their inner greedy, covetous, or angry nature. Since it can be hard to understand why someone has one character trait, it would therefore be even harder to understand why someone has all the character traits they have (as observed by other people) - and how those character traits result in their behavior in social interaction.

Character traits describe ways of relating to people or reacting to situations or ways of being. A trait will bring together references to the person's moral system (whether dishonest, a cheat, or a liar), to his or her instinctual makeup (impulsive), basic temperament (cheerful, optimistic, or pessimistic), complex ego functions (humorous, perceptive, brilliant, or superstitious), and basic attitudes toward the world (kind, trustful, or skeptical) and him- or herself (hesitant). So someone could be responsible (instinctual makeup), giving (basic attitude toward the world), fearless (basic attitude toward him- or herself), mean (moral system) and skillful (complex ego function).

The Communication of Emotion

Understanding what you are feeling is important in part because you might or might not reveal those feelings in conversation. Recognition of what we are feeling means that we acknowledge the significance of some event, which may also be an interpersonal interaction. There is a possibility of multiple emotions experienced virtually simultaneously or in rapid oscillation as we consider different aspects of the person or situation. Recognition of the different features that often interact with one another in a social situation allows for a richly faceted appraisal, and one's emotional experience is similarly more complex. Sometimes we might be aware that we are "unaware" of some of our feelings.

Just as understanding what we are feeling helps with self-disclosure of those feelings, knowing what the other people you are with are feeling also is obviously an important aspect in social interaction. The better we understand our own feelings, the more we can understand others because people have similar experiences of feelings. The better people understand how and why people act the way they do the more they can infer what is going on for them emotionally. One person in a social interaction may not be saying what they are feeling but the other people may be capable of figuring out or inferring what they are feeling. Showing an understanding of what other people are feeling shows an ability to empathize, as well as showing that you are sensitive and compassionate. How we infer others' emotions, and, for that matter, how we reflect on our own, depends on what we believe to be the causes of these emotional experiences. We identify certain emotions associated with certain behaviors and come to understand that if someone does this or that thing, then they are going to feel this or that as a response.

How emotion is communicated in a relationship is very important to social interaction. Based on the type of relationship, different types of emotion is going to be communicated. In a loving relationship, the emotion love is going to be communicated, for instance. This skill requires individuals to take into account several aspects of the relationship's dynamics (1) the interpersonal consequences of their emotional communication within the relationship for themselves and for the other, (2) how they maintain the relationship quality (e.g., equilibrium), or alter it (e.g., be deepening or attenuating it), and (3) how they apply power or control within the relationship. So if you express anger the circumstances might change based on the type of relationship. How you maintain the relationship will also be important after a display of anger. Also, obviously how power and control is applied in the relationship is going to be an issue when anger (or other emotions) are displayed.

How emotion is used by individuals to guide communication production is complicated. Some individuals disregard their own affective reactions until the level of arousal becomes so high that it cannot be ignored. They then may act according to their emotional response, but they might not know why. It is mere reaction, not considered communication production. Others might actively engage their affective state, readily recognize and consult their feelings in making decisions. Thus, some people orient to their communicative world through their emotions- hence the label "affective orientation".

Attachment Styles

If people differ in their motivation to maintain positive relationships with others, then we can expect people who show higher levels of such motivation to perform more positive, constructive behaviors in various ways more so than their peers. There is also something called attachment style - which is a persons characteristic pattern of expectations, needs, emotions, and behavior in social interactions and close relationships. Depending on how it is measured, attachment style characterizes the way people behave in a particular relationship (relationship specific style) or across relationships (global attachment style). Someone can be secure in their attachment style and find it relatively easy to get close to others and depend on them. Someone could not be secure but be avoidant, uncomfortable being close to others, doesn't trust them completely, and doesn't allow themselves to depend on them. Someone could also have an anxious attachment style and are nervous about how close people get to them and worry their partner doesn't love them or want them.

Gender Identity

There is a wide range of constructs that represent culturally based masculine and feminine self-definitions. These constructs can be recognized in terms of three facets of masculinity and femininity: representations of oneself as (1) possessing gender-typed personality traits and interests, (2) having male-typical versus female-typical relationships to others, and (3) being a member of the category of women or men, as that category is defined within a given society.

Gender identity, like gender roles, encompasses qualities that are regarded as typical or ideal of each sex in a society. Gender identity can thus refer to descriptive gender norms, defined as what is culturally usual for women or men in a society. In the descriptive sense, gender identity is the construal of oneself in terms of the culturally typical man or woman. Gender identity can also refer to injunctive (prescriptive) gender norms, defined as what is culturally ideal for women and men. In the injunctive sense, gender identity is the construal of oneself in terms of the best of male or female qualities.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism, as a fundamental trait of general personality, refers to an enduring tendency or disposition to experience negative emotional states. Individuals who score high on neuroticism are more likely than the average person to experience such feelings as anxiety, anger, guilt, and depression. They respond poorly to environmental stress, are likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening, and can experience minor frustrations as hopelessly overwhelming. They are often self-conscious and shy, and they may have trouble controlling urges and impulses when feeling upset. (McCrae and Costa, 2003)[]

Embarrassment

Embarrassment is the state of mortification, abashment, and chagrin that washes over us when social life takes an awkward turn and we suddenly face the prospect of undesired evaluations from others. It typically strikes without warning and causes startled, self-conscious feelings of ungainliness, conspicuousness, and befuddlement. Embarrassment is usually sudden, automatic, and brief; it hinges on the realization that one has made some misstep or that an interaction has gone awry, but such appraisals occur without deliberation or reflection, and embarrassment can be in full flower before one ever thinks things through.

Social Anxiety

In contrast, social anxiety is fretful disquiet that stems from the prospect of evaluations from others in the absence of any predicament. It occurs when we believe ourselves to be subject to real, implied, or imagined social evaluation, and it takes the form of nervous concern for what others may be thinking, even when nothing has gone wrong. Unlike embarrassment, social anxiety often occurs over long periods of time, gradually waxing and waning. It depends on contemplation of social settings that portrays them as daunting and intimidating, so it is usually gradual, prolonged, and mindful (rather than automatic).

Shyness

Shyness occurs when social anxiety is paired with reticent, cautions, and guarded social behavior. Shy behavior may range from mild inhibition, involving bashful timidity or wary watchfulness, to stronger distancing behavior that can include total withdrawal form social settings. That is a broad range, and no one pattern of behavior reliably distinguishes shyness form cooler, calmer states (such as those associated with introversion) that lead one to be quiet and reserved in the absence of any anxiety. Shy behavior may thus seem ambiguous to observers; it is obviously not gregarious and convivial, but whether it derives from shy trepidation, a mild manner, dullness, or unfriendly lack of interest may be hard to judge.

Proneness to Shame and Proneness to Guilt

How do people react to their own failures and transgressions? People vary considerably in how they feel when they recognize that they have failed or behaved badly. For example, given the same event--say, hurting a friend's feelings--an individual prone to guilt would be likely to respond by ruminating about the offensive remark, feeling bad about hurting a friend, and being compelled to apologize and make up for it. A shame-prone individual, instead, is likely to see the event as proof that he or she is a bad friend--indeed, a bad person. Feeling small and worthless, the shame-prone person may be inclined to slink away and avoid the friend for fear of further shame. When people feel shame they feel bad about themselves- "small", however when people feel guilt they feel their conscience and feel morally bad that they did something wrong or are "guilty". The two are so different there can be "shame-free" guilt and "guilt-free" shame.

People can also blame other people instead of feeling shame for themselves, or maybe people that suffer from the pain and self-diminishment of shame may become defensive and angry and attempt to deflect blame outward. Because shame and guilt are painful emotions providing negative feedback for wrong-doing, it is often assumed that both motivate individuals to do the right thing. That isn't necessarily the case, however, someone could experience a lot of shame and still do lots of bad things (or do lots of bad things and not experience any shame).

Goals, Motivation and Perception

Social interaction can be motivated by a number of different drives. Motivation will affect the perceptual activity that takes place. The social situation in which A sees B at a party, or in some other open setting, and is deciding whether or not to interact with B. The problem here is one of predicting B's behavior - will B be a sufficiently entertaining and agreeable person to talk to? Is he likely to be able to tell A the way? etc. The prediction here is about behavior which is relevant to A's goals in this particular situation, and whether B is likely to be able to help him to realize these goals.

If A decides to initiate an encounter with B, A's initial problem is to select an appropriate interaction style from his repertoire that is suitable for B. If A behaves differently to others of different sex, age and social class (as everyone in fact does), he needs to be able to categorize B in terms of these variables, and whatever others are salient for him. At this stage then A is concerned with certain demographic and personality variables in B; once this is done that particular perceptual task is over, though some revision be made in the light of further experience of B.

During the encounter itself, A is concerned with eliciting certain responses from B, or with establishing and maintaining some relationship with B. In order to do this, A needs continuous information about B's reaction to his own behavior, so that he can modify it if necessary. A may simply want B to like him, or he may have other quite personal motivations with regard to B, or A may want B to learn, buy, vote, or respond in terms of mainly professional goals which A has. In either case A needs to know what progress he is making with B. He may be concerned with B's attitude towards himself, with B's emotional state, with B's degree of understanding, or with other aspects of B's response.

In some situations A's main concern is with B's opinions, attitudes, beliefs or values. This is obviously true of social survey interviews, but in many more informal situations people want to find out how far their own attitudes have social support from others, and how far their ideas about the outside world are correct. People want positive reinforcement and feedback about their ideas and themselves.

In other situations, for example interviews for personnel selection and personality assessment, the main object may be to assess personality, either in order to understand its clinical origins, or to decide upon its suitability for a given job. In other situations, such as law courts, or interviews with administrators, it is more a matter of deciding what sanctions to apply; here the personality is matched against some social norm of the behavior that is required.

The effect of interpersonal attitudes

If A knows B well he will have already formed a detailed impression of B, and knows which styles of behavior to use with him. He will notice any deviation from B's normal behavior, and interpret it as a temporary state or mood. Similarly A will be able to interpret B's behavior better - he will know when B is anxious or cross better than could someone who has not met B before. Generally speaking the better A knows B the more accurate his judgments of B's personality are. This is not always so, since A and B become involved in an intricate relationship, and A's judgement can become highly distorted.

If A likes or dislikes B, his judgments of B become systematically affected. If he likes B he will perceive B as liking A, more than he actually does. If A likes B, he also tends to see A in a favorable light, and bias all judgments in a socially desirable direction. This may be the result of interaction: if A likes B he will behave more pleasantly towards B, and elicit more favorable behavior from B.

If A likes B he will see B as more like himself and having more similar attitudes than is really the case. This effect is called assimilation, or simple projection; it would be expected that if A and B are really alike, A's judgments will be more accurate.This kind of projection is quite different from the Freudian kind - in which people fail to see their shortcomings in themselves, and instead believe that other people suffer from them.

If B behaves aggressively towards A, this affects A's perception of B in an interesting way. The immediate effect is for B to be seen as aggressive, and to be judged unfavorably in other ways. However, this effect may be mitigated when the causes of B's aggressive behavior can readily be seen. This is an excellent example of the shift from personal to impersonal causation. If A thinks that he has done badly on a task, for which B could reasonably blame him, he will feel less negative towards B.

Sources of Aggression

Various environmental stressors can lead to aggression - when the social rules are broken or subjects are exposed to stressors such as extremes of heat or noise for long or unpredictable periods of time. Consistent invasions of a comfortable personal space, working under crowded conditions or living in a densely inhabited area can often lead immediately to aggression. The frustration-aggression hypothesis states that the blocking of goal-directed behavior leads to aggression. However, experimental results show that only when goal blocking is severe and arbitrary or unjustifiably enacted does it lead to aggression. The perception of why a goal was blocked may be inaccurate. The situational conditions that lead to heightened arousal facilitate overt aggression under certain circumstances (such as competitiveness, loud noise, social conditions with exercise (dancing), etc).

Sources of Altruism

The number and actions of bystanders can influence altruistic behavior. When a subject is alone he or she might be more likely to respond to cries of help than when in the company of others. Also the activity of the other people in the situation influences behavior. Observing others helping might make one more likely to help. Reinforcement in one situat