1.2.2 Nowadays

Nowadays, standardized tests involving several types of puzzles are used to rank a person's

intelligence in the main cognitive areas. The resulting score is compared to the average

intelligence of the test-taker’s countrymen by converting it to a rank positioned on the normal

distribution function9. This rank corresponds to the proportion of people who share the same

intelligence degree in the same age-group. There have been several legitimate I.Q. tests used by

psychologists for decades ; some are aimed at children whereas others are for adults. They differ

by author, scale, standard deviation, subtests19, main cognitive skills focus, but their mean (or

Esperance) is usually set at 100.

Most tests assess the main intelligence categories, albeit in different groupings of reaction time,

verbal, numerical, spatial, abstract, or logical etc.… subtests. Abstract reasoning is particularly

interesting as it impacts every other skill36 and can be perceived as a kind of core fluid

intelligence79 influencing cognitive abilities and their related psychological traits.

Points are, at that moment, attributed to all subtests, and afterwards, a rank in the form of a

global score, or a percentile29, is calculated and given to the “patient”. A percentile is the

percentage of people who did worse than the test-taker on the assessment.

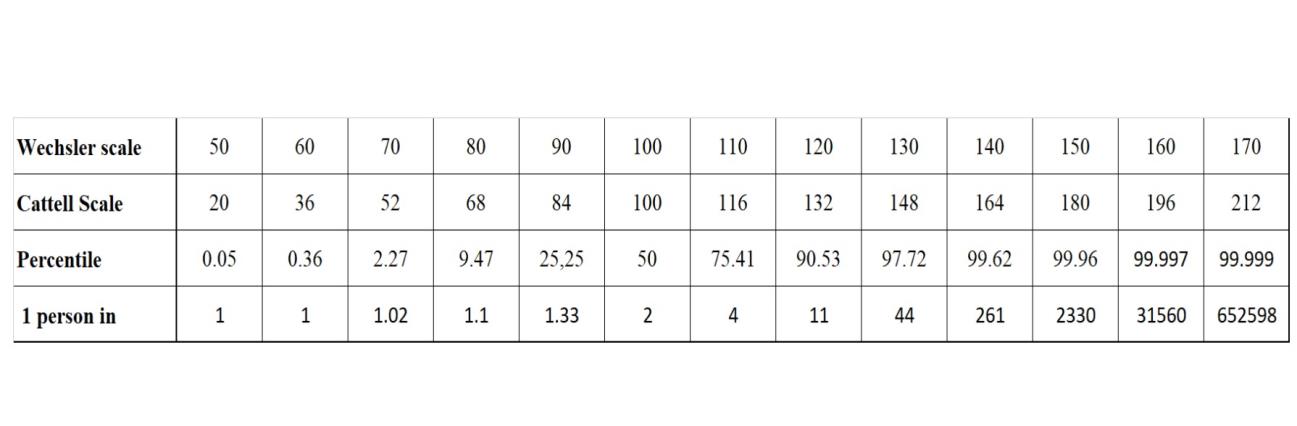

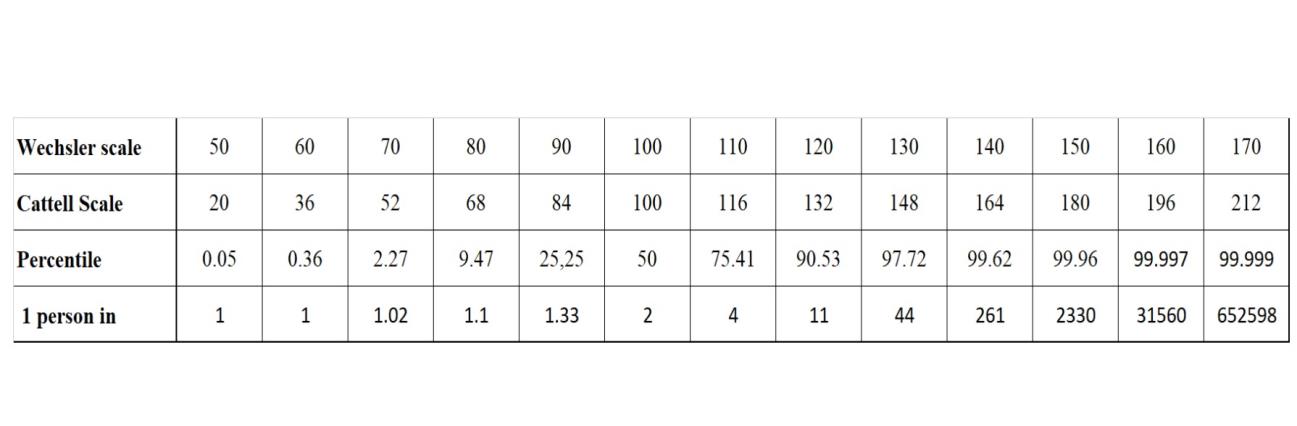

The most famous tests, available nowadays, are the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale10 (or

WAIS), the Stanford-Binet11, the Cattell Culture Fair Intelligence Test12, the Raven Progressive

Matrices13 and a few others. Each of them employs a particular scale.

The scale I resort to, in this book, is the most widely used in the world (except in the USA): the

Wechsler scale22.

The average of most modern tests is set at 100 by default. It is considered mean intelligence. On

the Wechsler Scale, the scores follow a bell curve with a fat hump of 68% of people who fall

within the average range: between 85 and 115; 16% are above 115, 16% are below 85. On the

Cattell Scale the ranges boundaries are distinct.

Untimed tests for high-range244 intelligence exist as well. Sadly, due to the limited number of

people with such high cognitive abilities, they are normed with smaller groups and frequently

developed outside of official structures. As a result, they are considered fairly unreliable.

Two main scales:

To explain the table22 above, a person with an I.Q. score of 120 on the Wechsler Scale does better than 90.53% of

the population of his or her country and such a level (or above) is found in 1 person out of 11. Similarly, a person

with an I.Q. score of 90, does better than 25.25% of people and such a score (or higher) can be found in 100 people

out of 133 (1/1.33).

1.3 Are Official Tests Accurate?

Every so often, I meet people who distrust I.Q. tests assuming they cannot measure intelligence

properly.

Is there any basis to that assumption, or are tests really trustworthy?

1.3.1 I.Q. Tests are Flawed Tools.

A handful of flaws have been observed, over the years, which put a damper on the notion of the

all-powerful, unquestionable I.Q. test score. These defects are to be attributed to the

configuration of the test itself, but also, to the emotional state of the test-taker.

Test Issues

I.Q. tests are imperfect tools, yet, so far, nothing else has been able to measure intelligence

comprehensively, with some degree of certainty, in a scientific way.

I.Q. measuring occasions several significant concerns:

- The tests measure “The g factor”16-17 (the general intelligence factor), a component directly

correlated to efficient cognitive functioning. This factor, involved in cerebral performance also

characterizes the perception of what intelligence represents. But these I.Q. assessments only

account for about 70% of “g”18; consequently 30% of intelligence is never considered. A WAIS

result, for example, is often given with an accuracy of 95% by providing a confidence interval19,

hence the range sometimes given to the patient (ex: 123-133) instead of a single number (ex:

130), the confidence level of which, would be much lower.

In short, only part of your intelligence is considered in an I.Q. test and the result is a little

uncertain.

- An I.Q. score somewhat depends on the type of test used. Some tests give a slight advantage248-

249 to people who are good at 3D puzzles, others to people who work better with letters or who

are highly logical. Some tests items involuntarily measure knowledge245 instead of inference;

others possess more than one possible answer246-247, in this way, quantifying mainstream thinking

instead of cleverness.

So, if you take 3 different assessments you will get 3 dissimilar I.Q. scores for the same

“volume” of intelligence.

- Since these tests aim at quantifying one’s ability to find solutions to problems one has never

met before250, one cannot become excessively familiar with these types of questions for fear of

invalidating the accuracy of the calculated score.

Therefore, having taken a previous I.Q. test may potentially alter the result of a future one.

- The most troublesome test feature for very clever individuals is the existence of test ceilings20-

21. Because putting together normative groups of superior intelligence is arduous, I.Q. tests are

particularly designed for people of average intelligence41 (I.Q. score from 85 to 115). For others,

the score is merely an approximation to be confirmed by further I.Q. test-taking, which, as we

have just seen, may actually prevent precision. The WAIS’ maximum score is 160, but its real

upper limit is undoubtedly closer to 135-140 due to additional ceilings in all subtests251. As a

result, the higher the total, the more artificially lowered it gets. People in the upper realms of

intelligence typically hit every ceiling and end up with official scores around 135-140 unless

specific extended subtests252 are added. In addition, the higher one ranks on the curve, the

stronger one’s aptitude in pattern-detection when presented with a great deal of seemingly

unrelated information253. This is never considered in regular I.Q. tests, in which simple patterns

are employed.

So, the less average your intelligence, the less accurately assessed by I.Q. tests it is.

- In psychometrics254 (psychological measurements), a global I.Q. score is valid if all the

subtests’ indexes are homogeneous. When subtests scatter23 is too great, the psychologist is not

able to calculate a meaningful average. The test-taker may feel cheated for not receiving a

concrete result, even if subtests can be interpreted individually. Besides, when subtest averaging

is possible, a global I.Q. score doesn’t necessarily hold much meaning on its own. Indeed,

discrepancies between subtests highlight dissimilar functioning at the same intelligence level. It

is especially interesting, to Neuro-atypicals255-256 (cognitively nonconforming people) for self-

awareness reasons, as well as clever individuals as, the further removed from the average, the

more spread out the subtests84. In any case, abstract reasoning, having an impact on every

subtest36; it is undoubtedly the most trustworthy beacon to gauge somebody’s intelligence.

Consequently, a global I.Q. score may be meaningless if subtests are too uneven.

- I.Q. tests largely estimate male reasoning proficiency37-38 in spatial and numerical logic.

Consequently, the higher the score is, the greater the gap between the genders in the number of

persons represented at each increment. This is confirmed by the enhanced variability of male

brains’ I.Q. scores24-25 compared to females. I’m referring to the brain structure here and not

necessarily the sex of its owner. Still, men’s scores are naturally more spread out, being more

present at both ends of the curve257 (in the lower and higher ranges), than women’s scores which

are primarily found in the middle.

In a nutshell, I.Q. tests may be less suited to account for women’s intelligence.

- The average I.Q. score varies from country to country27. Since it is a comparison to the rest of a

given population, a score appraised with a test aimed at a specific country is only valid in that

country258-259-260. Similarly, taking a test in a foreign language, even for fluent people, artificially

lowers one’s verbal I.Q261. score as well as the whole evaluation.

So, if you take an I.Q. test devised for foreigners or in a foreign language you may be at a

disadvantage.

The Flynn Effect:

The Flynn effect28 (noticed by James R. Flynn) is an apparent score increase, attributed, for the

most part, to greater life complexity65 and heightened guessing habits64, which, in some measure,

improve pattern recognition to favor higher scores. That gain is merely statistical and doesn’t

reflect actual betterment in cognitive ability. To make up for that artificial progression, I.Q. tests

are overhauled every ten years262, so that, the same scores calculated decades ago and nowadays

remain equivalent.

The hidden decline in intelligence:

For environmental reasons263, to some extent, the tendency to become parents later in life43 and

the higher percentage of childlessness among high I.Q. people40-43, intelligence has been

declining, mainly in first world countries28-43, for over a century. Yet, that decline, which has

been masked by the Flynn effect, has commonly been ignored. Undeniably, in spite of the ever-

rising ceiling of tests, we don’t seem that much smarter than our ancestors.

Actually, a deterioration in I.Q. scores42 as well as an important decrease in intellectual

capacity43 has been noticed in the impoverishment of vocabulary, hue differentiation, reflexes,

memory, and attention span. That slow drop in intelligence, by nearly three points per decade264-

265, is worrisome, as it causes an alteration of the distribution, primarily at its extremities. To

illustrate296, a drop of 3 points can be estimated to lower the proportion of people with a score

above 120 by over 30% and that of gifted people by roughly 40%; at the same time scores under

80 increase by about 40%.

People’s Issues

An I.Q. test-taker is classically given a score or a range (sometimes a percentile29) by a

psychometrician. Such a test can be sought, out of curiosity, or to ascertain that everything is

normal in the cognitive area, but if one is looking to establish the presence of giftedness266 (I.Q.

in the top 2% of a given population), the result provided merely helps the practitioner who also

requires a psychological evaluation to establish such a diagnosis0.

Why is it so? Most importantly because one’s state of mind impacts psychometric results!

Under most circumstances, in spite of life ups and downs, the intelligence of adults78 remains

stable. One’s I.Q. level as measured by tests, however, is bound to vary, fluctuating according to

one’s emotional balance267.

A test score can be rendered inaccurate because of personal impairment, may it be, fleeting or

permanent:

- I.Q. results fluctuate according to one’s level of confidence271, health, anxiety267, or energy

level during the test. Therefore, someone’s I.Q. could amount to 145 on a good day, but only to

120 on a bad day, or even as low as 100 on an even worse day.

- Dyslexia30, dyscalculia31, depression35-104-267, social anxiety disorder32, bilingualism33, and

ADHD34 add extra hurdles to a correct I.Q. measurement:

- Dyslexia269, dyscalculia270 and ADHD268 increase reflection time.

- Social anxiety347 makes it harder to concentrate when one is being watched.

-Depression impairs104 memory, attention span, cognitive processing, and decision-making

abilities thus, reduces scores significantly. Since giftedness frequently entails existential

depression105, it also goes hand in hand with unreliability in I.Q. scores.

Being bilingual reduces the quantity of words one knows in either language (compared to

monolingual speakers, on average272), whereas total vocabulary in both languages is larger. As a

result, test-measured verbal I.Q., typically evaluated in only one language, gets artificially

truncated.

Therefore, although having become fluent, as an adult, in at least one additional language,

compared to your peers in the same cultural background (for example, being an American who

speaks Spanish fluently if you’re not of Hispanic decent) is a sign of high intelligence44-45-46,

your verbal subtest score gets artificially reduced.

1.3.2 Why use an I.Q. scale at all?

Why bother employing an I.Q. scale10, at all, if I.Q. tests are somewhat unreliable?

In spite of the aforementioned flaws, I.Q. tests allow the assessment of human cognitive abilities,

at a specific time, and under well-defined circumstances, even though emotional and

psychological impairments remain unheeded.

Besides, the Intelligence Quotient is a well-known concept that has been capturing people’s

imagination. Who hasn’t heard of the I.Q. score of various scientists and authors, rumored to be

through the roof, even if its consequences on aptitude or psychology remain unclear? Einstein’s

I.Q. score of 16047 is quite famous, although it appears to be a meaningless oversimplification of

what his intelligence, in physics, represented.

Moreover, it’s an easy way to discern the degree of intelligence involved, as well as its frequency.

The Intelligence Quotient theory, by itself, is already pretty comprehensive. Contrary to what the

uninitiated may think, the concept of I.Q. is not in competition with “Emotional Intelligence”49-50

(also known as E.Q.) or with the “Theory of Multiple Intelligences”51-52. Even if I.Q. tests do not

directly measure social intelligence, creativity, imagination, learning ability or long-term

memory, these notions are all highly positively correlated to “g”53-54-55.

In a nutshell, the Intelligence Quotient theory works, scientifically speaking, even if its

implementation is not entirely trustworthy because of the human factor. The integration of

psychology, in my opinion, is paramount to avoid misestimating the subject’s level.

My goal, in this book, is to do away with any kind of emotional, learning, health issues which

weaken the assessment’s precision and to observe the direct consequences of “g”18, characterized

by our inner emotional mechanisms and noticeable behaviors.

This approach offers a good approximation of the extent of one’s intelligence throughout one’s

life, in a global, holistic way, regardless of ups and downs, impairments, subtests ceilings, and

lack of access to a sometimes pricey, psychometric test.

2. Variations in I.Q. Scores

Many studies about identical twins suggest intelligence is largely genetic48-86 the rest being

attributed to environmental67 (food quality, pollution), social67 (lack of brain stimulation) or even

medical reasons67-68.

2.1 Genetics: Variations in Brain Structure

The differences in I.Q. levels essentially originate in the brain structure56. As seen earlier, the

tests evaluate “g”, the general fluid intelligence18: problem-solving and learning skills. Because

half of “g” relates to how rapidly the nervous influx is propagated through the brain69 via its

neurons, the more efficient the brain is:

1- the lower the dendrite density60, permitting a greater brain plasticity.

2- the higher the density of Glial Cells58, for a more direct transfer of information.

3- the higher the myelination of the axons57, increasing the swiftness of neurological signals.

Similarly, the greater the brain performance is:

1- the higher the curvature of the Corpus Callosum58, determining the efficiency with which

both hemispheres interact.

2- the lower the need for glucose consumption59, decreasing fatigue resulting from the same

task.

Besides, as intelligence rises, the electrical signal speed in the brain increases. When this signal

is strong enough, instead of naturally fading rapidly, it eventually reaches brain areas unsolicited

by the current task. This situation known as low latent inhibition61-62-63 increases creativity in

people with elevated I.Q. scores.

2.2 Environment, Society and Healthcare: Variations in Nurture

Other differences in intelligence stem from various other issues. A child growing up in a low

intellectually stimulating milieu or with poor schooling67 will undoubtedly have difficulties

evolving harmoniously and will lose potential brain power.

Malnutrition67, disease and lack of access to medical care68 are also factors leading to a decrease

in potential intelligence.

At the same time, head injury (permanently) or depression70 (transiently) can alter proper brain

functioning and artificially lower an I.Q. score.

2.3 I.Q. Scores Discrepancy

Since intelligence is both impacted by nature and nurture, it isn’t uniformly scattered throughout

the world, but rather, typically exists in clusters of similar levels71-72-73 in countries, social and

professional groups, families etc…

However, this is a controversial27 topic as many claim that I.Q. tests, which were originally

designed for flourishing countries of the Western world, are not a good measure of intelligence

for certain cultures. Furthermore, in no way do I subscribe to the idea of entire races being less

intelligent than others.

On the other hand, being aware of these discrepancies permits the reader, living outside of the

USA, to use, with some accuracy, the I.Q. tests aimed at US residents provided at the end of this

book.