The Science of Meaning and Purpose

What does the research show? First, it is vital to recognize that studies do indicate that a strong religious belief correlates with a rich sense of meaning and purpose. Research on the psychology of religion illustrates that “for many, the most salient core psychological function of religion is to provide a sense of meaning and purpose in life” (Batson and Stocks, 149) Survey-based studies affirm such individually-oriented psychological research. For example a study of the population of Memphis found that the extent to which religion has salience in a person’s life correlates with a heightened sense of meaning and purpose (Petersen and Roy, “Religiosity, Anxiety, and Meaning and Purpose”). Another study used the General Social Survey, which tracks demographic, behavioral, and attitudinal questions across the United States. The researcher investigated how the degree of belief in God relates to a personal sense of life purpose. The data showed that people who indicated they are confident in the existence of God self-report a higher sense of life purpose compared to those who believe but occasionally doubt, and to nonbelievers (Cranney, “Do People Who Believe in God Report More Meaning in Their Lives?).

Parallels exist in global comparative research on religion and life purpose. One study encompassed 79 countries, using the World Values Survey. It found that more religious people in more religious countries experience a greater sense of life satisfaction across a variety of dimensions, including life meaning and purpose (Okulicz-Kozaryna, “Religiosity and Life Satisfaction Across Nations”). A 2007 survey by Gallup of 84 countries used the following question: “Do you feel your life has an important meaning or purpose?” The report on this survey highlighted the following as the brief summary: “Takeaway: Regardless of whether they affiliate themselves with a religion, more than 8 in 10 respondents across 84 countries say their lives have an important meaning or purpose. However, religion does make a difference: Those who claim no religious affiliation are more than twice as likely as those who do claim one to say they do not feel their lives have an important purpose” (Crabtree and B. Pelham, “The Complex Relationship Between Religion and Purpose”).

Such generalized takeaways provide support for mainstream opinions and religion-oriented thinkers who use such findings to support their claims that religion is the way to gain meaning and purpose. Yet digging deeper into the data raises questions about the evidence for such claims. For example, the study cited above on 79 countries also found that more religious people have less life satisfaction, including a sense of meaning and purpose, in less religious countries. Moreover, forms of worship that do not promote social connectedness do not correlate with a heightened sense of life satisfaction. Other studies illustrate similar findings. For instance, religious affiliation with community belonging leads to a higher degree of life satisfaction than religious devotion in private settings (Bergan and McConatha, “Religiosity and Life Satisfaction”). Another investigation underscored that extrinsic religious devotion, meaning a focus on religion for means such as in-group participation and social status, correlates with higher happiness and life meaning. However, intrinsic religious orientation, defined as religion that is deeply personal and defining one’s lifestyle, does not correlate with a greater sense of happiness and life meaning (Sillick and Cathcart, “The Relationship

Between Religious Orientation and Happiness”). These results show that socially-oriented religious practice in religious communities leads to a stronger sense of life meaning and purpose, while private and inner-oriented religious practice does not. In that case, is it religion or social and community bonds that lead to a deep sense of life meaning?

Courtsey of Cerina Gillilan

Research conclusively demonstrates that social affiliation is key to a deep sense of life purpose, regardless of religious affiliation. As an example, 4 studies showed significant correlation between whether people experience a sense of belonging and their perception of life meaning and purpose. Study 1 highlighted a correlation between questions asking for a sense of belonging and life purpose at the same time. Study 2 strove to remove the possible biasing that may occur by asking these questions at the same time. It first asked people about their sense of belonging, and 3 weeks later inquired into their sense of life meaning. The data was similarly indicative of a clear correlation between belonging and life meaning. Studies 3 and 4 primed participants to experience a sense of belonging and a variety of other experiences, and found that priming people to experience belonging resulted in the highest perception of life meaning for study participants (Lambert et. al., “To Belong Is to Matter”). A meta-review of many studies on life meaning and purpose similarly indicates social belonging as vital to a sense of life purpose (Steger, “Making Meaning”).

Such findings should not be surprising. Much recent social neuroscience underscores the vital role of social bonds for how our brains function. Indeed, our brain is inherently designed to be sociable, as part of our evolutionary development. The force of evolution selected for mutations that make our brains more social, as human ancestors best survived in groups, and those most capable of being socially oriented tended to outcompete those who were not. Thus, social neuroscience research indicates that when we engage with others, we experience an intimate brain to brain linkup. That neural bridge lets us affect the brain and thus the body of everyone we engage with, just as they do to us. The more strongly we connect with someone emotionally, the greater the mutual force. The resulting feelings have far-reaching consequences that ripple throughout our body, as our brain releases hormones that regulate all biological systems. A sense of meaning and purpose is thus neurologically correlated to social connectedness, and consequently our mental and physical well-being (Goleman).

In fact, research shows that the important thing is simply to have a sense of meaning and purpose in life, regardless of the source of the purpose . Going back to Frankl, his research suggests the crucial thing for individuals surviving and thriving is to develop a personal sense of individual purpose and confidence in a collective purpose for society itself, what he terms the “will-to-meaning and purpose.” Frankl himself worked to help people find meaning and purpose in their lives. He did so by helping prisoners in concentration camps, and later patients in his private practice as a psychiatrist, to remember their joys, sorrows, sacrifices, and blessings, thereby bringing to mind the meaning and purposefulness of their lives as already lived. According to Frankl, meaning and purpose can be found in any situation within which people find themselves. He emphasizes the existential meaning and purposefulness of suffering and tragedy in life as testimonies to human courage and dignity, as exemplified both in the concentration camps and beyond. Frankl argues that not only is life charged with meaning and purpose, but this meaning and purpose implies responsibility, namely the responsibility upon oneself to discover meaning and purpose, both as an individual and as a member of a larger social collective.

Courtesy of Cerina Gillilan

Frankl’s approach to psychotherapy came to be called logotherapy, and forms part of a broader therapeutic practice known as existential psychotherapy. This philosophically-informed therapy stems from the notion that internal tensions and conflicts stem from one’s confrontation with the challenges of the nature of life itself, and relate back to the notions brought up by Sartre and other existentialist philosophers. These challenges, according to Irvin Yalom in his Existential Psychotherapy, include: facing the reality and the responsibility of our freedom; dealing with the inevitability of death; the stress of individual isolation; finally, the difficulty of finding meaning in life (Yalom). These four issues correlate to what existential therapy holds as the four key dimensions of human existence, the physical, social, personal and spiritual realms, based on extensive psychological research and therapy practice (Cooper; Mathers).

So then why do studies show that a sense of life meaning and purpose correlates with religion? One reason is that so much of the research on this question has been conducted in the United States. And it just so happens that in the United States, religious communities have come to provide the kind of things that contribute to a sense of life meaning and purpose.

For example, in the contemporary United States, religion is the main venue that provides strong social and community connections. Likewise, within religious circles in the United States, there is much more focus on finding meaning and purpose, and clear answers are provided. The prominent anthropologist Clifford Geertz specifically described religion as a system for helping people find meaning and purpose through giving answers to the problem of the existence of chaos and suffering (Geertz). Furthermore, religion has been one of the most common sources of ritual experiences, especially in the United States. Research on rituals shows their importance in maintaining and transmitting cultural values, including what a specific culture perceives as the key elements of meaning and purpose. Scholars also highlight how rituals serve as a vital contributor to social bonding and community belonging.

Religious communities also provide many opportunities for serving others. These three factors – reflection on life’s basic questions, strong community and social ties, and civic engagement – are the three key sources of how people acquire a strong sense of meaning and purpose, according to the research.

Courtsey of Cerina Gillilan

Other societies with less religious predominance in the public sphere do not necessarily suffer from a lesser sense of meaning and purpose (McMahon). While in the US, religion is a predominant if weakening social force, this is not the case for all other societies, either today or in the past. Plenty of other societies had and have much less religious presence in the public sphere. Purpose and meaning also do not correlate with levels of wealth – surprisingly, many contemporary poorer countries have a greater average sense of meaning and purpose among their citizenry than those in rich countries (Oishi and Diener, “Residents of Poor Nations Have a Greater Sense of Meaning in Life”).

How do people in more secularly-oriented societies than the United States gain a sense of meaning and purpose? Well, here is an example. Mike met regularly with friends and acquaintances from his neighborhood in a large building. There, he enjoyed listening to presentations about big life questions: on the meaning of life, on the nature of morality, on ethical behavior, etc. He participated in study circles that engaged with these questions in more depth. Mike sang, danced, and enjoyed musical performances there. Together with others, he volunteered to help clean up the streets and build housing for poor people in the neighborhood. Through these activities, Mike gained social bonds and community connections, a chance to serve others, and an opportunity to reflect on life’s big questions – all the components that lead to a sense of meaning and purpose in life.

Mike’s full name is not Michael, but Mikhail, and his experience describes the prototypical experience of former Soviet citizens in state-sponsored community activities. The former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev described in his memoirs how much he and other Soviet citizens enjoyed such events: according to him, “everybody was keen to participate” (35). The Soviet Union is typically perceived as a militaristic and grey society, with a government that oriented all of its efforts to taking over the world. Well, that’s simply not true, as the Soviet authorities put a lot of effort into providing its citizens with opportunities to find meaning and purpose in life, as well as fun and pleasure – although they also certainly wanted to spread communism throughout the world, and put a lot of efforts into this goal as well (Tsipursky, “Active and Conscious;” “Having Fun”).

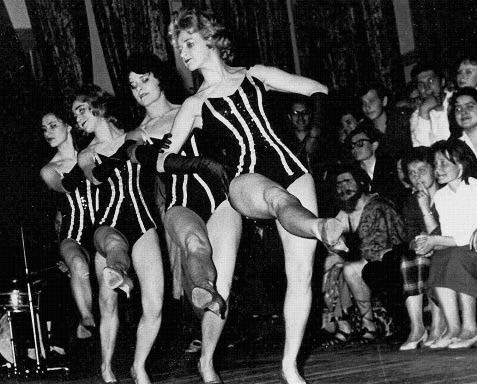

This early 1960s photograph shows a performance from a scene in a Soviet opera, named “Arkhimed,” held at a Soviet club. The photograph comes from the private archive of M. A. Lebedeva. For more on “Arkhimed,” see my scholarly work (Tsipursky, “Having Fun” ).

To understand how the USSR’s government helped its citizens gain a greater sense of meaning and purpose, I spent a decade investigating government reports in archives across the Soviet Union, exploring national and local newspapers, read memoirs and diaries, and interviewed more than fifty former Soviet citizens. The answer: to a large extent, through government-sponsored community and cultural centers called kluby (clubs). In many ways these venues replaced the social function provided by churches, offering Soviet citizens social and community connections, chances for serving others, and venues to reflect on meaning and purpose in life, in a setting that combined state sponsorship with grassroots engagement. Soviet clubs also hosted rituals and celebrations, which served to help people enjoy themselves and find meaning and purpose, and also to further the government’s political agenda (Tsipursky, “Integration, Celebration”).

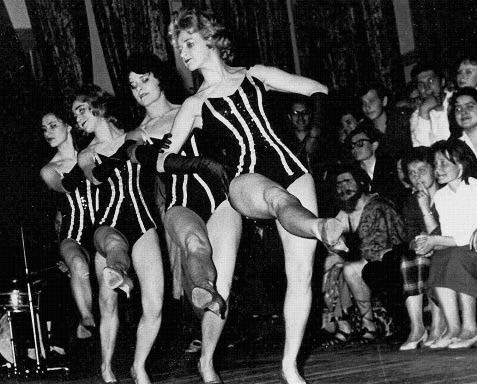

This photograph shows a banquet held after a performance of “Arkhimed.” The photograph also comes from the private archive of M. A. Lebedeva.

Present-day societies with a more secular orientation than the United States have similar stories to tell, as illustrated by research on contemporary Denmark and Sweden. Most Danes and Swedes do not worship any god. At the same time these countries score at the very top of the “happiness index,” have very low crime and corruption rates, great educational systems, strong economies, well-supported arts, free health care, and egalitarian social policies. They have a wide variety of strong social institutions that provide community connections, opportunities for serving others, and other benefits that religion provides in the United States (Zuckerman).

From another cultural perspective, a significant strain in Eastern worldviews holds the search for meaning and purpose itself as irrelevant. For instance, Legalism, a Chinese philosophical tradition, rejected the notion that one should even try to find a purpose in life, and focused only on pragmatic knowledge. A more prominent and better-known Chinese belief system, Confucianism, holds that one should find meaning and purpose in everyday existence, focusing on being instead of doing, and not devote much effort to finding meaning and purpose outside of this everyday experience (Tu).

Informed by an Eastern-based philosophy, Alan Watts promoted the idea to western audiences that the sense of self is an illusion, that we are all part of a larger whole. He advocated abandoning the search for an individual meaning and purpose, which he perceived as a harmful western cultural construct (Watts).

Another Eastern-informed perspective comes from Jon Kabat-Zinn. This prominent scholar and popularizer of meditation and mindfulness proposed relying on these practices to find your life purpose. Specifically, he discussed the importance of meditating on our personal vision and blueprint of what is most important in life in order to grasp our innermost values (Kabat-Zinn). As you see, there are a wide variety of perspectives on meaning and purpose. Believing in God and going to church is far from the only way to attain these qualities. You can gain them in non-religious venues that provide opportunities for community ties and a chance to reflect on life meaning and purpose, just as religious communities have traditionally offered.

Furthermore, research indicates that those who engage with such deep questions in a setting that does not expect conformity to a specific dogma overall gain a deeper perception of meaning and purpose (Wong, “Meaning in Life”). In other words, the most impactful sense of meaning and purpose stems from an intentional analysis of one’s self understanding and path in life and a consequent experience of personal agency, the quality of living intentionally. To be clear, one can find deep meaning and purpose from belief in a higher power, but it is best if one comes to that conclusion oneself after deep self-reflection and analysis, as opposed to just conforming to group and social norms. Yet in the United States there are few non-explicitly religious channels to reflect on life meaning and purpose. This workbook provides one such channel, drawing on academic studies as does all Intentional Insights content. The next section lists specific research-based strategies and exercises for gaining purpose and meaning in life.

Set aside 5 to 10 minutes to complete the following

Take a few minutes to think about how this information about the research on meaning and purpose impacts your own perspective on your personal sense of meaning and purpose.

Write down your thoughts and then proceed onward.