Several tests involved rabbits, which were strapped down facing the detonation site in order

to measure the blast’s effect on the eyes. The rabbits were awakened just before detonation

by applying an electric shock to their noses, ensuring their eyes were open when the bomb

exploded.

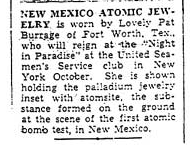

Photograph by Peter Goin: Nuclear Landscapes

29

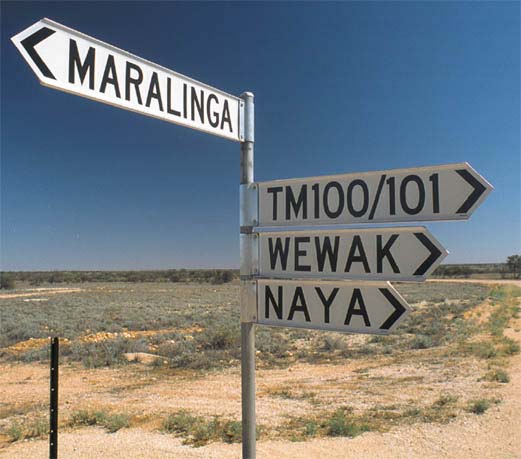

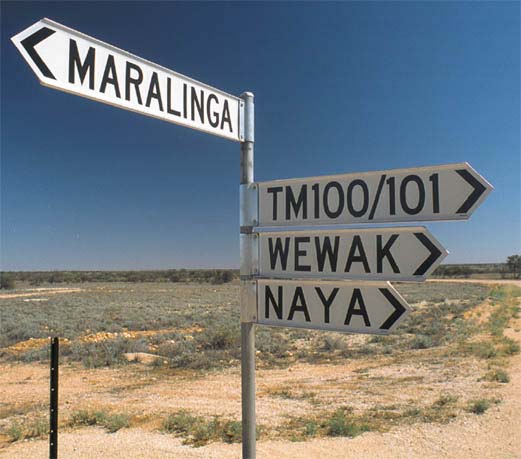

Nuclear Testing in Australia

12 nuclear bombs have been exploded in Australia. All were above-ground

tests carried out by Great Britain between 1952 and 1957. Further small-

scale tests were continued until 1963.

Monte Bello Islands

(3 detonations)

Maralinga

(7 detonations)

Emu Field

(2 detonations)

Operation Hurricane

(Monte Bello Island)

03 Oct 1952 (25kT)

Operation Buffalo (Maralinga)

Operation Totem

‘one tree’: 27 Sept 1956 (12.9kT)

(Emu Field)

‘marcoo’: 04 Oct 1956 (1.4kT)

‘T1’: 14 Oct 1953 (9.1kT)

‘kite’: 11 Oct 1956 (2.9kT)

‘T2’: 26 Oct 1953 (9.1kT)

‘breakaway’: 22 Oct 1956 (10.8kT)

Operation Mosaic

Antler (Maralinga)

(Monte Bello Island)

‘tadie’: 14 Sept 1957 (0.93kT)

‘G1’: 16 May 1956 (13.5kT) ‘biak’: 25 Sept 1957 (5.67kT)

‘G2’: 19 June 1956 (56.0kT) ‘taranaki’: 09 Oct 1957 (26.6kT)

30

In September 1950, Britain approached Australian Prime Minister Menzies

to ask for a favour. They wanted to use Australia to explode some nuclear

weapons. Unfortunately, they told us, the technology was a secret, and they

couldn’t tell us exactly what effects it would have. Australia would just have

to trust them that it would be totally harmless and safe.

Menzies said yes, on the spot, without consulting the Australian people, scientific advisors, or even his own government. Members of his cabinet were only informed once preparations

of the testing sites were well underway.

From 1952 to 1957, twelve above-ground nuclear bombs were exploded on the Australian

mainland, several of them larger than the Hiroshima bomb (≈15kT). Nine of these were on

land inhabited by nomadic aboriginal tribes. The Native Patrol Officer was given the impos-

sible task of locating and warning the Aborigines, who were scattered over more than

100,000 square kilometres.

A 1985 Australian Royal Commission investigation into the nuclear tests found that “There

was virtually complete government control of the Australian media reporting of the Hurri-

cane test and the lead-up to it, thus ensuring that the Australian news media reported only

what the UK Government wished. […] This was to be a recurrent theme throughout the en-

tire weapons testing program.”

Bad safety practice, accidents, and following cover-ups were to be the rule rather than the

exception. The 1985 report lists “departures, some serious and some minor, from compli-

ance with the prescribed radiation protection policy and standards during the test program.”

This included getting pilots to fly planes into radioactive clouds to take samples, and send-

ing divers into contaminated water, in neither case with proper safety equipment or decon-

tamination procedures.

At least eight of the 12 explosions were carried out in bad weather conditions, despite previous calculations showing this would lead to unsafe fallout over populated regions.

• The Monte Bello Islands were an unacceptable location for testing because of the strong

winds blowing on-shore, which resulted in radioactive fallout over the mainland after

each test. After the third test on the island, fallout over Port Hedland exceeded the maxi-

mum acceptable level for civilians as used today. This was omitted from reports pre-

sented to the government at the time.

• The Totem 1 tests at Emu Field threw a radioactive ‘black cloud’ over the aboriginal vil-

lages of Wallatinna and Welbourn Hill downwind from the test site. Various illnesses

ensued and one boy went blind. Contamination had been underestimated by a factor of 3.

• All four Buffalo tests were fired in bad weather conditions, which contaminated

Maralinga Village and areas beyond Coober Pedy. Only a lucky wind change at the last

minute saved Adelaide from fallout.

• No ‘acceptable’ levels of radioactive contamination were set by the government for the

final three Antler tests, but the Radiation Advisory Committee approved contamination

doses twice as strong as usual. Nonetheless, levels from the third test exceeded even these

levels.

31

In 1997 Britain made assurances to the European Court of Human Rights that there was no

intention to expose any servicemen or civilians to radiation during the tests. However, in

2001 it was revealed that this was not the case. During the Buffalo trials, twenty four Aus-

tralian servicemen were deliberately given excessive doses of radiation. They were ordered

to run, walk and crawl over Ground Zero hours after detonation. According to the British

defense ministry spokesperson, "These were not nuclear tests as such, these were radiation tests on clothing. We were not testing people, we were testing the clothing. People have

never been used as guinea pigs." It is also alleged that two groups of seriously mentally and physically handicapped people had been taken to a test area shortly before one of the nuclear tests, and were never seen again.

Many smaller, unofficial explosions were carried out at the test sites. They were designed

to investigate the performance of various components of a nuclear device, and mostly in-

volved radioactive materials in conjunction with conventional high explosives.

The first series, known as Kittens, was conducted at Emu in 1953 without formal Australian Government approval and without advice being provided to the Australian Government by either Australian or UK scientists. Subsequent series were known as Rats, Tims and Vixen. The explosions (ironically labelled ‘safety experiments’) scattered at least 24

kilograms of radioactive cobalt and plutonium pellets across the landscape. British scientists did not inform Australians of the existence of these pellets, and many personnel were exposed to dangerous radiation as a result.

In a half-hearted and unsuccessful attempt at a ‘clean-up’ after the tests, the British

ploughed the testing areas, effectively distributing the radioactive minerals deeper into the ground and making the subsequent Australian clean-up attempt far more difficult and expensive.

The Australian project to clean up the Emu and Maralinga test sites once and for all started

in 1994, with the final report published earlier this year. In the executive summary to this

report it is written that “None of the contamination of concern arose from the so-called ma-

jor trials—the testing of nuclear weapons by evoking a nuclear detonation. Without the mi-

nor trials at Maralinga, the rehabilitation program

would have been short and simple.” The program was

completed within budget and on schedule, despite be-

ing frequently hampered by grossly incorrect UK re-

cords which failed to record the locations of radioactive

waste, among other details.

A$104 million was the cost estimated by the

Australian Government in 1994 for the clean-up. De-

spite the 1985 Royal Commission report recommend-

ing the UK bear the costs, an agreement between the

countries saw the UK pay A$45 million as a final set-

tlement. No money was given by the UK to the aborigi-

nal communities or Australian servicemen as compen-

sation.

Following rehabilitation, the Monte Bello Islands are

now part of a Western Australian national marine park.

32

fun nuclear facts

India

China

As of 1998, 2050 nuclear tests have

0.1%

2%

Pakistan

France

been carried out (528 atmospheric

0.1%

10%

tests and 1522 underground).

Britain

2%

United States

Fallout from tests has been, or

51%

will be, responsible for 17,000

nuclear

U

deaths in the U.S. alone. 1.2

testing by

country

million civilians in Russia

Soviet Union

have weakened immune sys-

35%

tems as a result of tests there.

Israel

China

0.6% India

1.5%

France

0.1%

1.5%

Pakistan

Britain

As at February

0.1%

0.6%

this year, there were

United States

34.8%

approximately 30,000

nuclear

intact nuclear warheads

stockpiles

by country

throughout the world.

17,500 of these are

considered operational.

Soviet Union

60.9%

$3.5 trillion: Amount the United States spent between 1940

and 1995 to prepare to fight a nuclear war.

$27 billion: Amount the United States spends annually to

prepare to fight a nuclear war.

sources:

•

National Geographic, ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’, Nov 2002

•

Centre for Defense Information, Washington DC

•

Oklahoma Geologial Survey Observatory Catalog Of Nuclear Explosions: a list of

all known nuclear explosions worldwide, up to July 14, 1998. Available at http://

www.batguano.com/nuclear/nuccatalog.html.

•

Federation of American Scientists

33

SCIENCE AND NUCLEAR WEAPONS:

Contrasting Accounts of Nuclear Explosions

e

“To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven; the

same key opens the gates of hell.” - Buddhist proverb

34

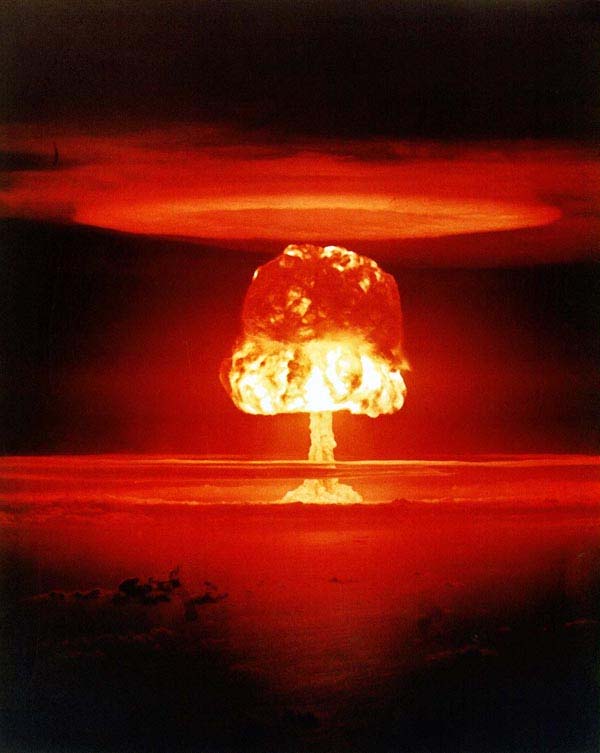

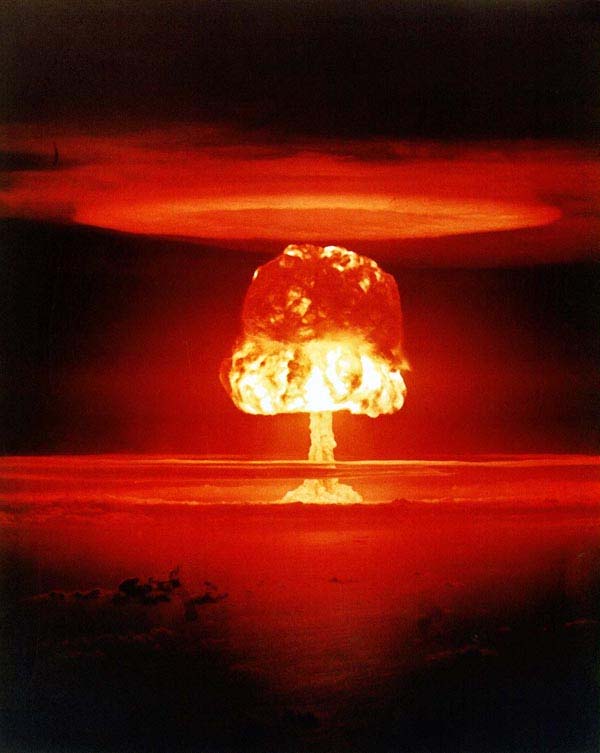

THE TRINITY TEST

An account of the first nuclear bomb test

by Richard Feynman, physicist

After we’d made the calculations, the next thing that happened, of

course, was the test. I went straight out to the site and we waited there,

twenty miles away. Time comes, and this tremendous flash out there is so

bright that I duck, and I see this purple splotch on the floor of the truck.

I said, “That’s not it. That’s an after-image.” So I look back up, and I see

this white light changing into yellow and then into orange. Clouds form

and disappear again—from the compression and expansion of the shock

wave.

Finally, after about a minute and a half, there’s suddenly a tremen-

dous noise—BANG, and then a rumble, like thunder—and that’s what

convinced me. Nobody had said a word during this whole thing. We were

all just watching quietly. But this sound released everybody—released me

particularly because the solidity of the sound at that distance meant that it

had really worked.

The man standing next to me said, “What’s that?”

I said, “That was the Bomb.”

After the thing went off, there was tremendous excitement at Los

Alamos. Everybody had parties, we all ran around. I sat on the end of a

jeep and beat drums and so on. But one man, I remember, Bob Wilson,

was just sitting there moping.

I said, “What are you moping about?”

He said, “It’s a terrible thing that we made.”

I said, “But you started it. You got us into it.”

You see, what happened to me—what happened to the rest of

us—is we started for a good reason, then you’re working very hard to ac-

complish something and it’s a pleasure, it’s excitement. And you stop

thinking, you know, you just stop. Bob Wilson was the only one who was

still thinking about it, at that moment.

—Extracted and abridged from “Surely You’re Joking, Mr Feynman!”,

Richard P. Feynman, 1992, Vintage, p135-6

35

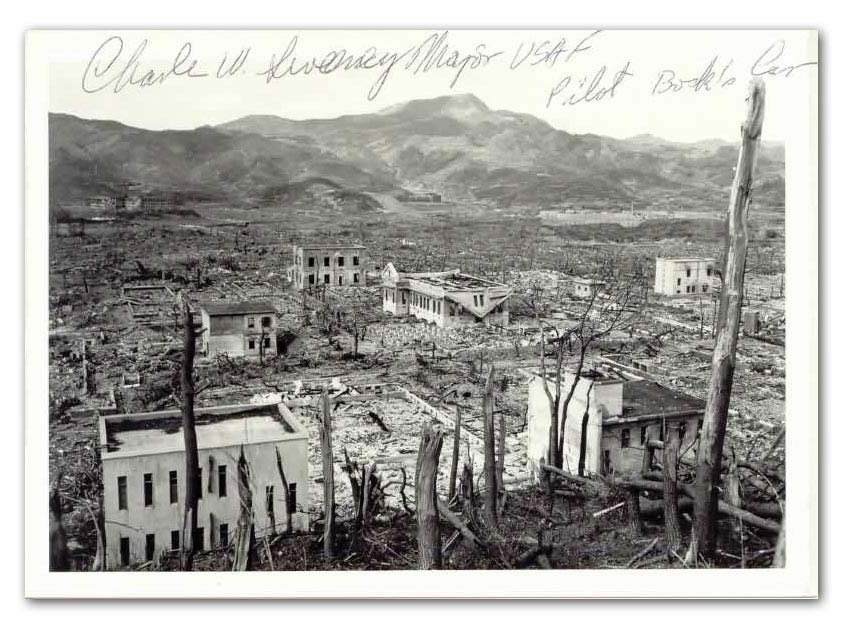

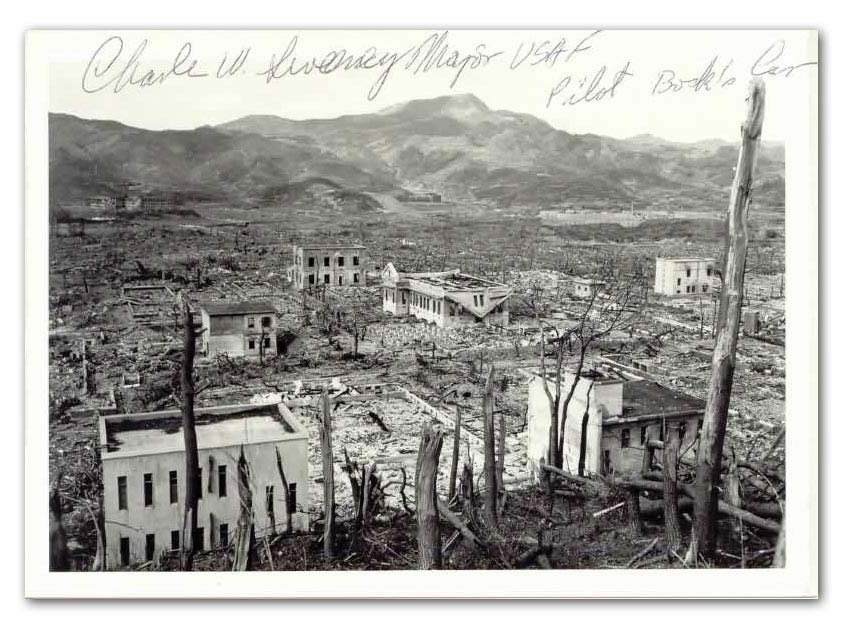

THE HIROSHIMA BOMB

An account of the first nuclear attack

by Michihiko Hachiya, physician and director

of Hiroshima Communications Hospital.

Dr. Tabuchi, and old friend from Ushita, came in. His face and hands

had been burned though not badly, and after an exchange of greetings, I

asked if he knew what had happened.

“I was in the backyard pruning some trees when it exploded,” he

answered. “The first thing I knew, there was a blinding white flash of

light, and a wave of intense heat struck my cheek. This was odd, I

thought, when in the next instant there was a tremendous blast.

“The force of it knocked me clean over,” he continued, “but for-

tunately, it didn’t hurt me; and my wife wasn’t hurt either. But you should

have seen my house! It didn’t topple over, it just inclined. I have never

seen such a mess.”

“Don’t go,” I said. “Please tell us more of what occurred yester-

day.”

“It was a horrible sight,” said Dr. Tabuchi. “Hundreds of injured

people who were trying to escape to the hills passed our house. The sight

of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and

swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to

hang down like rags on a scarecrow. They moved like a line of ants. All

through the night, they went past our house, but this morning they had

stopped. I found them lying on both sides of the road so thick that it was

impossible to pass without stepping on them.”

I lay with my eyes shut while Dr. Tabuchi was talking, picturing in

my mind the horror he was describing. I neither saw nor heard Mr. Ka-

tsutani when he came in. It was not until I heard someone sobbing that

my attention was attracted, and I recognized my old friend. “I walked

along the railway tracks to get here [he said], but even they were littered

with electric wires and broken railway cars, and the dead and wounded

lay everywhere. When I reached the bridge, I saw a dreadful thing. It was

36

unbelievable. There was a man, stone dead, sitting on his bicycle as it

leaned against the bridge railing. It is hard to believe that such a thing

could happen!”

He repeated himself two or three times as if to convince himself

that what he said was true and then continued: “It seems that most of the

dead people were either on the bridge or beneath it. You could tell that

many had gone down to the river to get a drink of water and had died

where they lay. I saw a few live people still in the water, knocking against

the dead as they floated down the river. There must have been hundreds

and thousands who fled to the river to escape the fire and then drowned.

“The sight of the soldiers, though, was more dreadful than the

dead people floating down the river. I came on to I don’t know how

many, burned from the hips up; and where the skin had peeled, their

flesh was wet and mushy. They must have been wearing their military

caps because the black hair on top of their heads was not burned. It

made them look like they were wearing black lacquer bowls.

“And they had no faces! Their eyes, noses and mouths had been

burned away, and it looked like their ears had melted off. It was hard to

tell front from back. One soldier, whose features had been destroyed and

was left with his white teeth sticking out, asked me for some water, but I

didn’t have any. I clasped my hands and prayed for him. He didn’t say

anything more. His plea for water must have been his last words.”

—Extracted and abridged from “Hiroshima Diary”,

Michihiko Hachiya, 1955, Gollancz, p26-28

“I also had, as many did, a sense of jubilation at the scientific

achievement of splitting the atom […]. The full horror of the bomb

did not hit me until the following summer […]. Up to this point,

chemistry and physics had been for me a source of pure delight and

wonder, and I was insufficiently conscious, perhaps, of their nega-

tive powers. The atomic bombs shook me, as they did everybody.

Atomic or nuclear physics, one felt, could never again move with

the same innocence and lightheartedness as it had in the days of

Rutherford and the Curies.”

Oliver Sacks, “Uncle Tungsten”,

37

i

“The target was there, pretty as a picture. I made

the run, let the bomb go—that was my greatest

thrill!”

Nagasaki, August 1945

—Capt. Kermit K. Beahan, bombardier on the B-29 plane

Bock’s Car which dropped an atomic bomb on the city of

Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. The bomb made a crater one

mile in diameter and killed 74000 people in the next five

months. Beahan spent the night partying, as it was his

27th birthday.

38

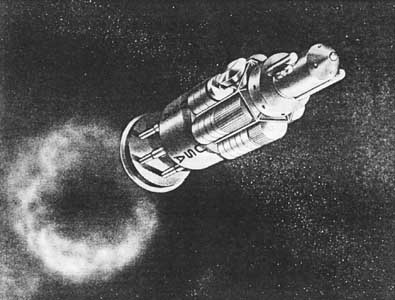

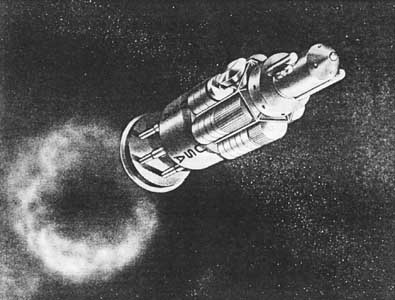

Great Uses for

nuclear weapons #3 :

Go to Mars

During the space race of the fifties and sixties,

the United States government hit on the great idea of using

nuclear explosions to blast a spacecraft off the Earth and

away to the Final Frontier. They liked the idea so much they

gave it a budget and a name: Project Orion.

Project Orion was a spacecraft which would carry several

hundred nuclear weapons as fuel. These bombs would be

ejected out the back of the craft and detonated at a ‘safe dis-

tance’ of about 50 metres. The resulting blast wave would hit

a specially designed disc at the back of the ship which would

reflect the energy and al ow the ship to ‘ride the wave’.

Some of the problems that needed to be overcome in the de-

sign included radiation shielding for the astronauts, and

shock absorption between the energy reflecting plate and the

rest of the ship. This was so that the initial jolt would not

shake the craft to pieces and the astronauts would not get

cancer.

Considering that about fifty detonations would be required

just to get the craft out of the atmosphere, the public seemed

justified in being a little concerned about nuclear fallout. Pub-

lic pressure, together with the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963

which prohibited explosions in space, resulted in the project’s

cancellation.

39

Atomic Era

On August 6, 1945 an atomic bomb called ‘Little Boy’ was dropped on the

Japanese city of Hiroshima. At 11:03 a.m., an Associated Press bulletin in-

formed the American public of the event. It only took a few hours before

the word ‘atomic’ had become the hot new way to flog consumer goods.

Before the trading day had closed, the bar at

the Washington Press Club was offering a gin and

Pernod concoction dubbed the “Atomic Cocktail”.

The week had not passed before Los Angeles estab-

lishments were promoting “Atom Bomb Dancers”.

A New York jewellery company was selling “atomic

inspired pin and earring sets” that were “as daring to

wear as it was to drop the first atom bomb.” And

within months, KIX Cereal was advertising its Atomic 'Bomb' Ring which it was offering

to kids for 15 cents and a cereal box top. (“Squint into secret lens and Zowie!… See real

atoms split to smithereens inside ring.”) 750,000 orders were placed. Even the Boy Scouts

of America jumped on the bandwagon with an Atomic Energy merit badge.

In the next few years, whole columns of the Los Angeles and New York Yellow

Pages filled with ’Atomic’ businesses such as the Atomic Hotel, Atomic Food Products,

Atomic Sportswear, Atom Cleaners, and even the Atomic Undergarment Co. The Las

Vegas Chamber of Commerce saw great promotional and tourist potential in the nearby

Nevada Testing Site, and offered tours to watch nuclear explosions. They also instituted

the ‘Miss Atomic Blast Contest’, where the winner wore a coronation bikini with an 88-

40

Pop Culture

carat diamond in the bikini top and a smaller diamond in the bikini

bottom.

The age of atomic pop culture had begun. To the average

American citizen the atomic bomb connoted power, ingenuity and

supremacy.

This fascination with uranium and the bomb made its way

into the cinemas. The 50s and 60s saw the release of movies in-

cluding Operation Uranium in 1965 (“It was terror disguised as a

woman!”), The Gamma People in 1956 (“Mad Dictator Rules

Country With Deadly Gamma Ray!”), and also in 1956

the movie The Atomic Man (“THIS was the deadliest

secret of all… the MAN with the RADIO-ACTIVE

BRAIN!”). Uranium was as exciting as gold during the

gold rush—and resulted in the wacky western-style

movies Uranium Boom (“The inside story of the atom-

age boom towns!”) and Dig That Uranium (“Boy—how

their Geiger counters click when they meet those babes

from the Badlands!”). And then there’s the simply peer-

Albuquerque New Mexico Journal

September 1945

less (and equally inexplicable) movie of 1953, Canadian

Mounties vs. Atomic Invaders.

Atomic war toys and games appeared

shortly after World War II, including a board game

that let players bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By

the time of the PC the craze was still going strong.

B-1 Bomber involved dropping warheads on Mos-

cow, and Nuclear War treated the subject with

black humour. The Atari game Missile Command

also dealt with nuclear warfare and had widespread

popularity. Trinity was made for Apple II series

computers and involved the original 1945 atomic

bomb test named Trinity, as well as the bombing

of Hiroshima and a future nuclear holocaust.

While kids were munching on ‘Atomic Fire

Ball’