CHAPTER VI

SIMPLE MONOPLANE MODELS

OF the variety of aëroplanes, there seems to be no end. Nature offers a bewildering variety of models in the innumerable birds and insects, which may be accepted as successful monoplanes. These, in turn, may be copied and modified indefinitely. The science of aviation is still so young that there is ample opportunity for invention and discovery for all, and every new trial adds something to our information, and carries the science a step nearer perfection.

It will be found an excellent plan to build, once and for all, a strong well proportioned motor base, and mount a powerful motor and well modeled propeller. A variety of planes may then be tested out by attaching them to this. The motor base will answer for practically all monoplane forms and many biplane models as well. Such a frame should be about three feet in length and carry one or better two motors, placed side by side.

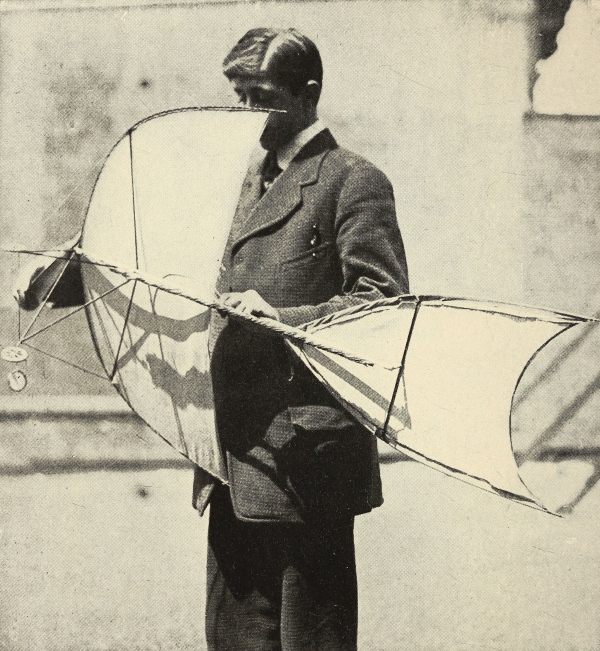

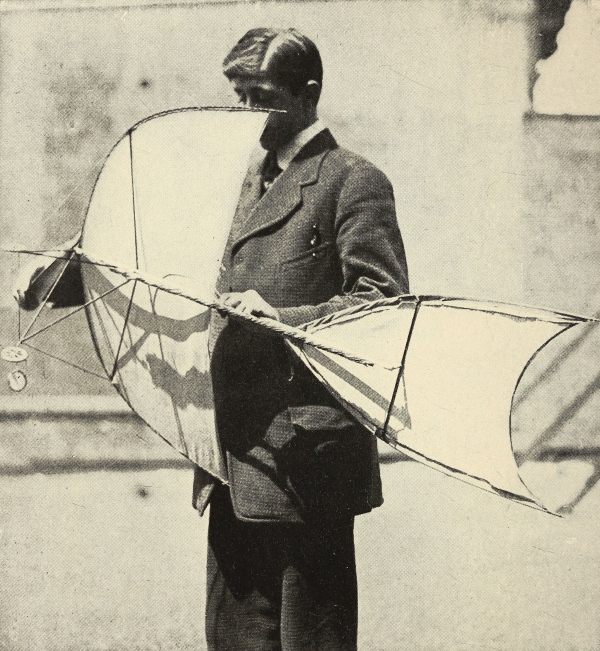

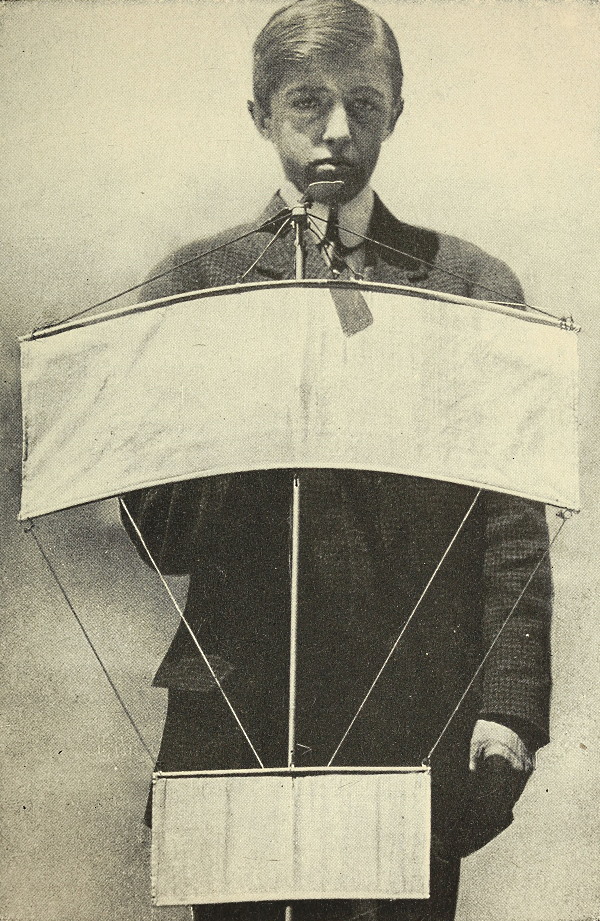

There is as much danger in providing too much lifting-surface in your aëroplane as too little. This fault is well illustrated in an exceedingly clever French model (Plate I). Although the model is well constructed, and appears ship-shape at first glance, it nevertheless has far too much surface and will not fly well. If the depth of the wings were reduced fully one half, it would have a much better chance.

The best lifting-planes are those which present a broad front or entering edge, but with comparatively little depth. The successful flying-machines, whether monoplanes or biplanes, use these very wide but shallow planes forward. The theory is of course that the air is caught for an instant beneath the plane and before it has a chance to slip off the sides, the wing has caught its very slight supporting power and moved on to new and undisturbed air.

With this rule in mind examine the model’s front plane once more. It will be seen that, as the air is caught under this broad surface, it will try to escape in all directions and set up currents of air. Instantly the broad plane loses its balance and tilts to one side or the other. No weighting of the plane can overcome this. If the plane were forced through the air at a very high speed a steady flight might be possible, but it is useless to try to overcome this tendency to tip and wabble.

The planes again are badly designed. A perfectly straight front or entering edge gives the best results. A certain stability is gained by curving the front plane slightly, this will be discussed later, but there is no excuse for the semicircle described in this case. Every inch of surface cut away from the front edge of the plane directly reduces its lifting power. The arrow like form of the rear plane does not matter because this is a stability plane, not a lifting plane. In this case the rear plane is twice the size it should be.

PLATE I. A Clever Folding Model. The Wings Are Broader than Need Be.

The propeller of this model is much too small, even if the size of the planes was correct. It is well placed however at the front of the model where it may turn in undisturbed air. The passage of these large planes, or any planes for that matter, is likely to cut up the air just as a ship churns the water into a wake behind it and the propeller does not work effectively in these eddies. The motor seems powerful and well braced, although it might be made even longer by carrying it to the extreme rear.

Several very useful ideas may be borrowed from the construction of the frame of this model. It is made entirely of metal, so jointed that it may be folded up into very compact form like an umbrella. The amateur model builder should not attempt anything so complicated, but an old umbrella frame may be used with good results in building a rigid frame. Use the steel rod of the umbrella as a backbone, and cut away the ribs you do not need. The others may be bent into various shapes to form the front or sides of the planes, the skids or braces. Such a construction is light and perfectly rigid.

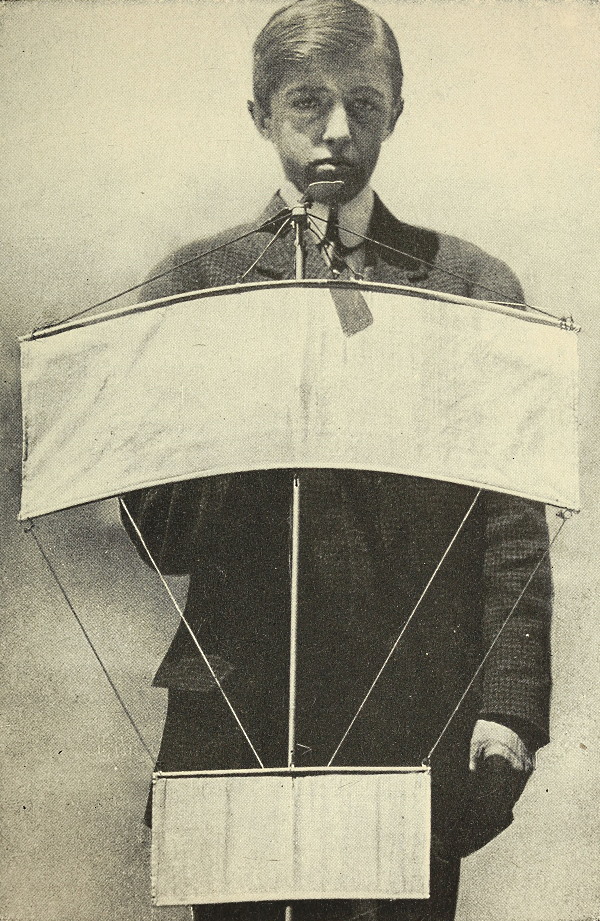

A very effective monoplane may be made by curving the front and rear edges of the forward plane, while keeping the rear or stability plane rectangular in shape (Plate 2). The curve of this model may be imitated to advantage, as well as the general proportions. Such a plane is less likely to be deflected by air currents than a straight entering-edge and insures longer and steadier flights. Should you be troubled by your model twisting from side to side in flight try curving the front edge of the forward plane.

This model is one of the easiest to make and is an excellent one for beginners. Build the two planes separately making the larger one about thirty inches in width and ten inches in depth, and the second one fifteen inches in width and ten inches in depth. The curved sticks may be worked up by using bamboo or dowel-sticks, soaking them in water and fastening them in a bowed position while damp and leaving them to dry. It may be found a good plan to use a heavier stick for the rear edge of the plane to gain stability.

A single stick about one half an inch in diameter may be used for the backbone. It will be found an excellent plan to attach the planes lightly to the main frame so that they may be adjusted before fixing them finally in position. Place them in the position shown in the accompanying photograph, and move them up and down until the flights are all that you expect, when they may be fastened for good and all. The bracing of this model is excellent and may be safely imitated. It enables one to tune up either plane and fix them rigidly in position. The propeller is very properly placed forward although it appears to be rather small. It is unnecessary to bother with any vertical rudder for this model since the curve of the front plane insures a reasonably straight flight.

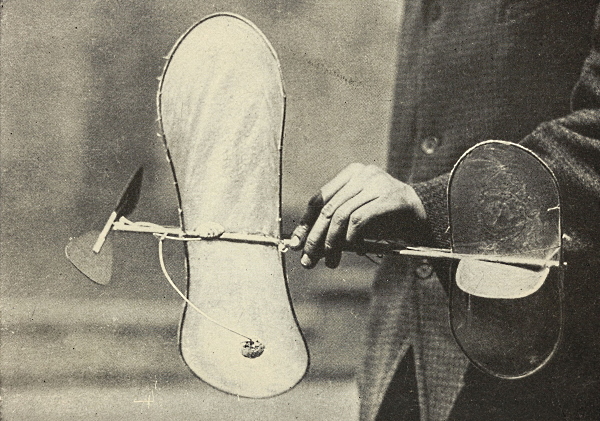

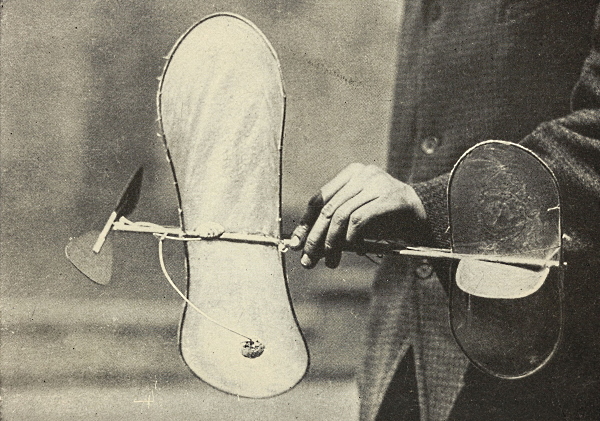

A popular French model which may be easily imitated consists of curved planes both front and rear (Plate 3). The curve of the planes is too complicated to be carried out in wood, but may be readily formed by bending a stiff wire to the desired shape. The front plane should be about twelve inches in width and four inches in depth. The rear should be about half this size and of the same form. The planes may be readily mounted on a small dowel stick. A small propeller and a motor a foot in length will answer. A small semi-circular fin should be set below the rear plane to act as rudder. First cover the frames with a stiff paper and after you have succeeded in adjusting it, this may be replaced by cloth. The model will not fly far, or very steadily, but it is interesting to practice with. The balance of the model is open to criticism; for the center of gravity appears to be too far forward.

PLATE II.

A Model Aëroplane Worth Imitating.

The simplest of all models to build, and not the least interesting, is the small paper monoplane (Plate 4). The planes which are slightly curved are formed of a stiff card which will hold its shape when bent into position. These may be attached to the main stick by inserting an edge into a groove in the stick and glueing in place. It is not well to construct these more than six inches in width over all.

One of the simplest monoplanes to construct is formed of a broad rectangular forward plane with a fan-shaped stability-plane at the rear (Plate 5). This is a French model which is said to have flown long distances; that is to say, 300 feet or more. It has several very interesting features. In the first place the combined area of its planes is doubtless greater than that of any other model here described. The vertical rudder which looks very shipshape and effective is very easy to build and the frame illustrates several new principles.

The frame or motor-base may be made of heavy dowel sticks or light lath as indicated in the photograph. It will be found simpler to avoid tapering the frame at the rear by merely constructing a stout rectangular base with a length two and one half times its width. The forward plane is slightly bowed or flexed. It will be found a good plan to construct the frame for the base and then bow a light strip at either end against the edge. By fastening the covering to these curved strips a smooth curved surface may be obtained.

The rear stability-plane may be stretched over a fan-shaped frame of strips or lath which is in turn fastened to the motor-base. Another plan is to attach the front and rear edges of the plane, the rear one being slightly longer, and stretch the covering over these leaving the sides free as in the photograph of the accompanying model. The vertical rudder is very simple, consisting of a piece of dowel stick sunk in the rear frame to which a rectangular piece of cloth is attached the front corner being pulled taut.

The spread of the planes appears to be considerably greater than needs be. Since the front plane is flexed it may be reduced one third or even one half in depth without reducing its lifting quality; although in this case it should be placed nearer the stability plane. This reduction would, of course, make an important saving in the weight of the craft. So large a model calls for two propellers which will prove more effective at the front rather than the rear of the machine. It might be well to carry the motors further back than has been done in this model thus gaining additional power.

Since the model is expected to rise unaided from the ground the question of the skids is very important. The design followed in the model is excellent. The front of the frame is supported by legs consisting of inverted triangles built of dowel sticks attached to the frame. The axle connecting the two runs on small wheels, such as may be borrowed from a toy automobile. The rear of the frame rests on a simple skid made of curved reed. These supports place the model at an angle which should enable it to rise easily without loss of power. There is a great deal of satisfaction in working on so large a model, the parts may be made stronger and there is less likelihood of its getting out of order.

Now turn from these broad planes to the rather slight model (Plate 6), and the faults of its proportion are at once obvious. The front plane is much too far back for stability. Such a model will glide fairly well, and, if the motor be powerful it will rise quickly, but a steady horizontal flight is out of the question. The size of the planes seems perilously small, and yet if they be well shaped and spaced they will prove large enough. This is just the sort of model a beginner is likely to make, and therefore serves a very useful purpose in pointing a lesson.

PLATE III.

An Ingenious French Model Made of Umbrella Wire.

It is not without its good points. The front plane has been carefully flexed and attached to the motor frame at a good angle. An interesting experiment has also been made in carrying the edges of the front plane a trifle behind the rear edge, thus making for stability. The vertical rudder above the rear stability-plane is well placed, although it appears rather small. The skids upon which the model rests and the proportion of the front to the rear elevation are excellent. It is a first rate plan in building such a model to attach the front plane temporarily to the motor-base, and move it back and forth in the trial flights until the best spacing has been found.