CHAPTER I

THE FIRST FLYING MACHINES

THE conquest of the air was not won by a happy accident of invention. Long before man learned to fly the science of aviation had to be created by investigation and experiment. At first with very crude attempts, a great many flying machines had to be built, and many lives sacrificed in flying them. The exact nature of the invisible air currents and the action of wings and planes, were to be learned before the delicate mechanism of the modern aëroplane was possible. Probably no other great invention has required such long and patient preparation.

In many ways the aëroplane is therefore a greater achievement than the steam engine or the steamboat. When Watt turned from watching his tea kettle to build his engine, he applied mechanical principles which had long been in actual use, and there were many experienced mechanics to help him. Robert Fulton, again, when he set up his engine, found the science of boat-building highly developed. The aviator had no such advantage. He must first of all build a craft which would keep afloat in the most unstable of mediums. A motive power had to be applied to suit these conditions, and the two must be so attuned that they would work perfectly together when the least slip would mean instant disaster. As we learn to realize these difficulties we will appreciate more than ever how marvellous a creation is the modern aëroplane.

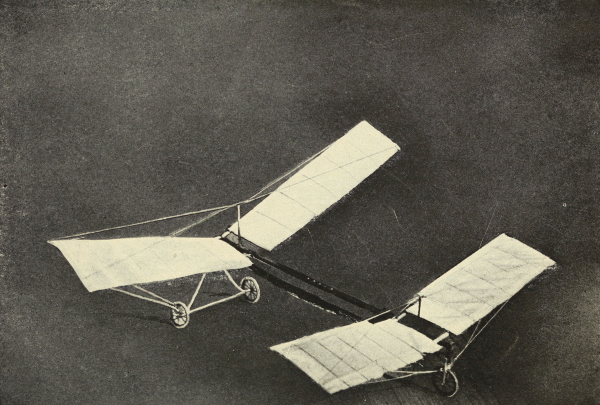

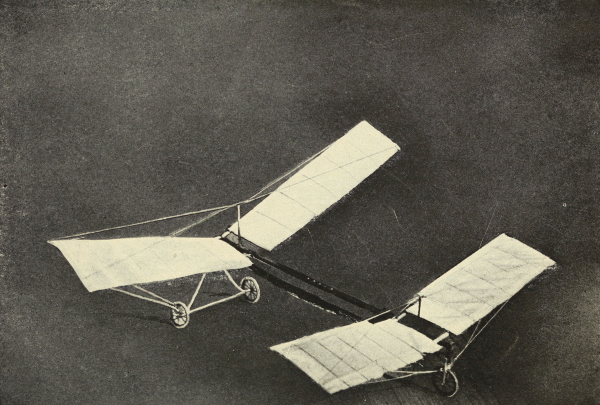

PLATE XII.

A Good Example of Tilted Planes.

Man has thought much about flying from the earliest times. The open air has always seemed the natural highway, and flying machines were invented hundreds of years before anyone dreamed of steamengines or steamboats. The ancient Greeks long ago spun wonderful tales of the mythical Daedalus and Icarus and their flight to the sun and back again. The first practical aviator seems to have been a Greek named Achytas, and we are told he invented a dove of wood propelled by heated air. There is another ancient record of a brass fly which made a short flight, so that we may be sure that even the ancients had their own ideas about heavier-than-air machines.

As far as we may judge from these quaint old records the early aviators attempted to fly with wings which they flapped about them in imitation of birds. About the year 67 A. D., during the reign of the Emperor Nero, an aviator named “Simon the Magician” made a public flight before a Roman crowd. According to the record, “He rose into the air through the assistance of demons. But St. Peter having offered a prayer, the action of the demons ceased and the magician was crushed in a fall and perished instantly.” The end of the account, which sounds very probable indeed, is the first aëronautical smash-up on record.

Even in these early days the interest in aëronautics appears to have been widespread. It is recorded that a British king named Baldud succeeded in flying over the city of Trinovante, but unfortunately fell and, landing on a temple, was instantly killed. In the eleventh century a Benedictine monk built a pair of wings modelled upon the poet Ovid’s description of those used by Daedalus, which was apparently a very uncertain model. The aviator jumped from a high tower against the wind, and, according to the record, sailed for 125 feet, when he fell and broke both his legs. That he should have attempted to fly against the wind, by the way, indicates some knowledge of aircraft.

If we may trust the rude folklore of the Middle Ages, the glider form of airship which anticipated the modern aëroplane was used with some success a thousand years ago. An inventor named Oliver of Malmesburg, built a glider and soared for 370 feet, which would be a creditable record for such a craft even in our day. A hundred years later a Saracen attempted to fly in the same way and was killed by a fall. The number of men who have given their lives to the cause of aviation in all these centuries of experiment must be considerable.

Meanwhile the kite and balloon had long been in use in China. There is no reason to doubt that kites were well understood and even put to practical use in time of war as early as 300 B. C. A Chinese general, Han Sin, is said to have actually signalled by kites to a beleaguered city that he was outside the walls and expected to lend assistance. And a French missionary visiting China in 1694 reported that he had seen the records of the coronation of the Emperor Fo Kien in 1306 which described the balloon ascensions that formed part of the ceremony.

The fifteenth century was the most active period in aëronautical experiments before our own. A number of intelligent minds worked at the problem and notable progress was made, although all fell short of flying. Even in the light of our present knowledge of aëronautics we must admire the thorough, scientific way the aviators went about their work five centuries ago. Many of their discoveries have been of great assistance to our modern aviators. Had these investigators possessed our modern machinery, of which they knew little or nothing, it is, very likely they would actually have flown.

One of the greatest of these investigators was Leonardo da Vinci, famous as architect and engineer as well as painter and sculptor. To begin at the beginning of the subject, he dissected the bodies of many birds and made careful, technical drawings to illustrate the theory of the action of wings. These drawings and descriptions are still preserved, and even to-day repay careful study. He also calculated with great detail the amount of force which would be necessary to drive such machines. Plans were prepared for flying machines of the heavier than air form to be driven by wings, and even by screw propellers, which was looking far into the future.

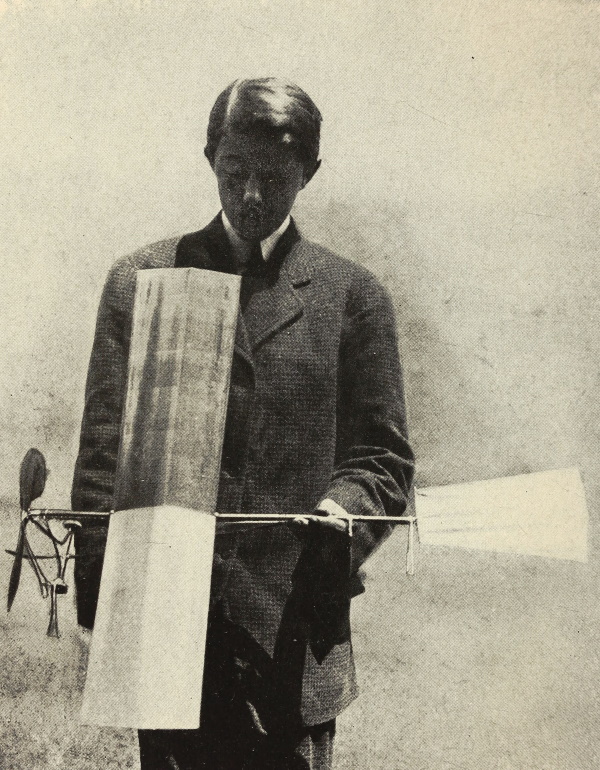

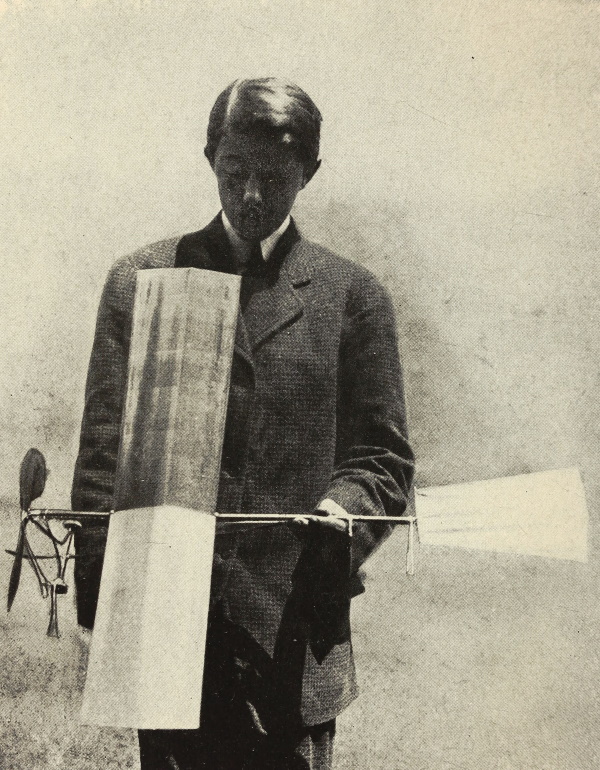

PLATE XIII.

A Serviceable Form Made of Wire.

Among all these early experiments the best record of actual flight was made by Batitta Dante, a brother of the great Italian poet. In 1456 Dante flew in a glider of his own construction for more than 800 feet at Perugia in Italy and a few years later he succeeded in flying in the same glider over Lake Trasimene. The glides made by the Wright Brothers while perfecting their machines seldom reached this length.

For several centuries it was believed that a lifting screw, if one could be built, would supply enough lifting power to support a heavier than air machine. Da Vinci experimented along this line for many years and even built a number of models with paper screws. This form of flying machine is called the helicopter. The plan was then abandoned for nearly five centuries and revived in our own century. The record of all the aviators and their experiments would fill many volumes.

The belief that man could learn to fly by flapping wings up and down was not given up until very recently. Nearly all the early machines were built on this principle. Man can never fly as the birds do because his muscles are differently grouped. In the birds the strongest muscles, the driving power, are in the chest at the base of the wings where they are most needed. It is amusing to find that while the birds are always flying before our eyes no one has guessed their secrets. Many attempts have been made to wrest their secrets from them by attaching dynometers to their wings to measure the force of the muscles but little has been learned in this way. One scientist calculated that a goose exerts 200 horse power while another investigator figured out that it was one tenth of one horse power. Many of the theories of flight have been quite as far apart. A great variety of false notions about flying had to be tried and from all these failures man slowly learned the road he must follow.