FM 3-21.11

a. Stealthy Reconnaissance. Stealthy reconnaissance emphasizes procedures and techniques that allow the unit to avoid detection and engagement by the enemy. It is more time-consuming than aggressive reconnaissance. To be effective, stealthy reconnaissance must rely primarily on dismounted elements that make maximum use of covered and concealed terrain. The company’s primary assets for stealthy reconnaissance are its infantry squads. (For a more detailed discussion of dismounted patrolling, refer to FM

7-10.)

b. Aggressive Reconnaissance. Aggressive reconnaissance is characterized by the speed and manner in which the reconnaissance element develops the situation once contact is made with an enemy force. A unit conducting aggressive reconnaissance uses both direct and indirect fires and movement to develop the situation rapidly. Therefore, the company typically uses mounted reconnaissance. In conducting a mounted patrol, the unit employs the principles of tactical movement to maintain security. The patrolling element maximizes the use of cover and concealment and conducts bounding overwatch as necessary to avoid detection. (For a more detailed discussion of tactical movement, refer to Chapter 3 of this manual.)

7-3.

RECONNAISSANCE BEFORE AND AFTER OPERATIONS

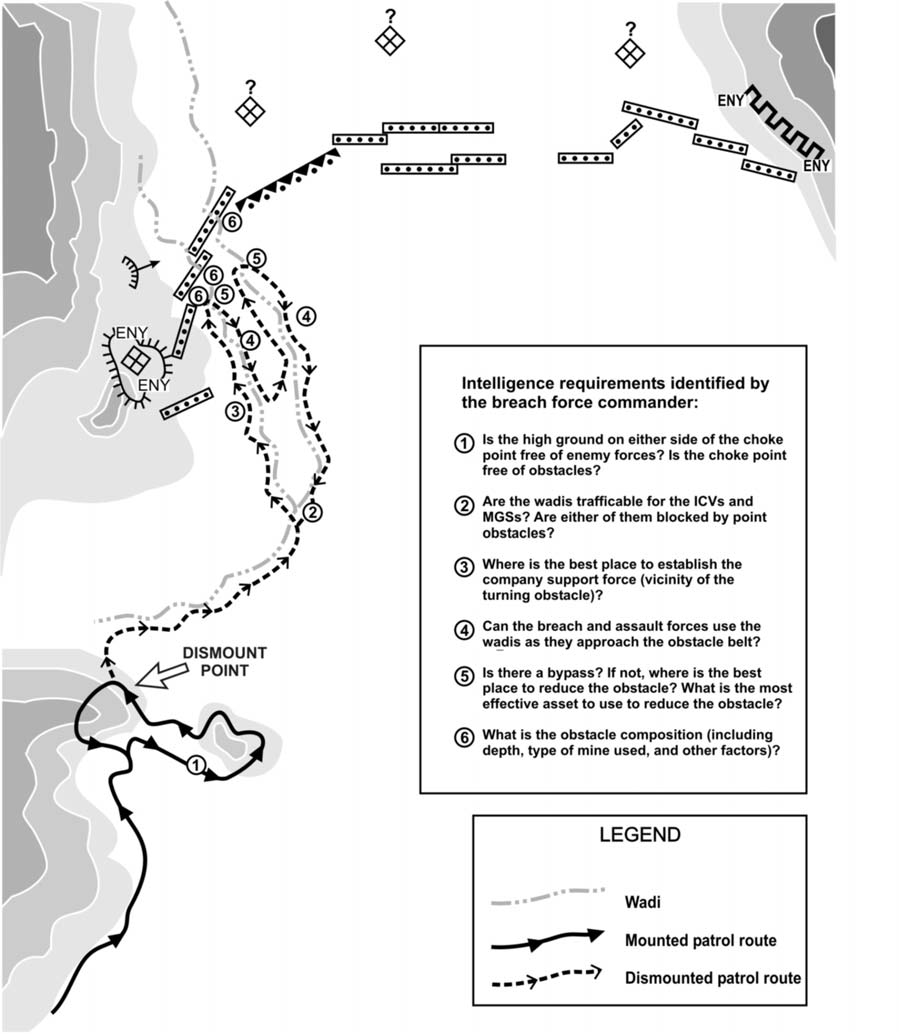

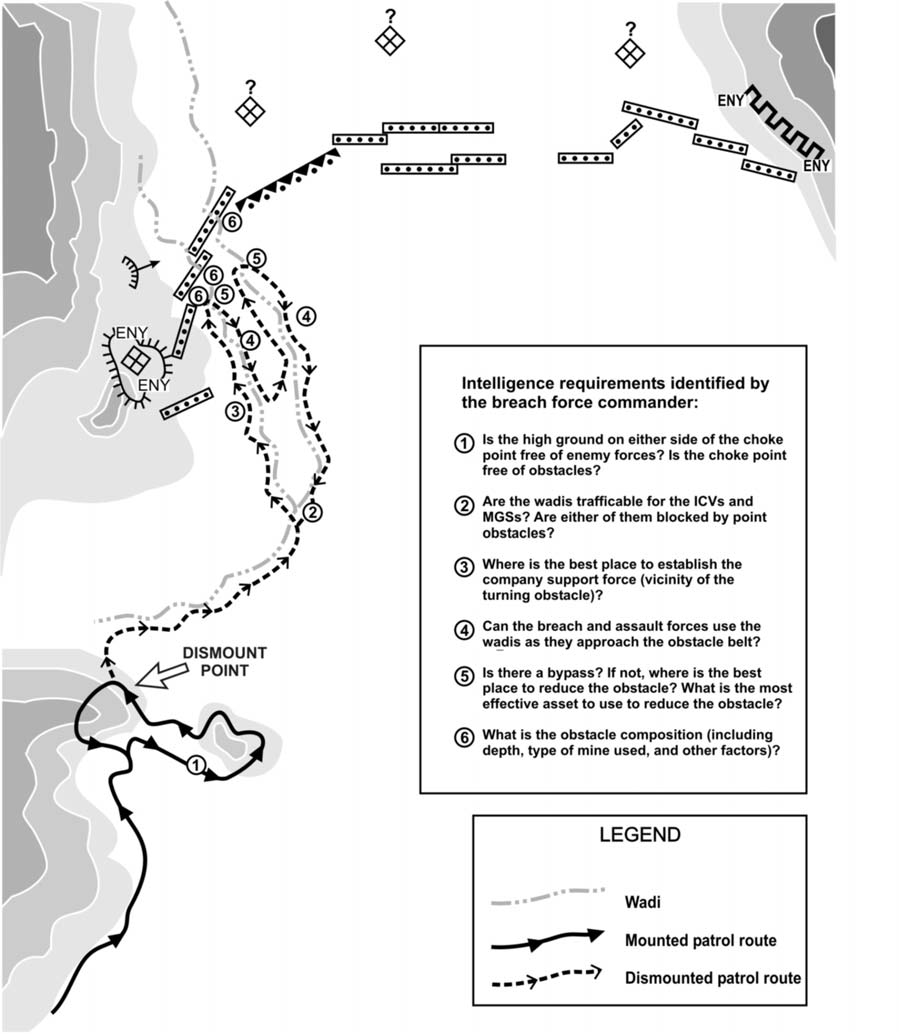

To be most effective, reconnaissance must be continuous--conducted before, during, and after operations. Before an operation, the company focuses its reconnaissance effort on filling gaps in its information about the enemy and terrain. (Figure 7-1 shows an example of company reconnaissance prior to an operation.) After an operation, the company normally conducts reconnaissance to enhance SU so it can maintain contact with the enemy and collect information for upcoming operations. Situations in which the company may conduct reconnaissance before or after an operation include the following:

• Reconnaissance by a quartering party of an assembly area and the associated route to it.

• Reconnaissance from the assembly area to the LD and in the vicinity of the LD before an offensive operation.

• Reconnaissance by infantry patrols to probe enemy positions for gaps prior to an attack or infiltration.

• Reconnaissance by infantry patrols to observe forward positions and guide mounted elements to key positions on the battlefield.

• Reconnaissance by dismounted patrols (normally infantry and engineers) to locate bypasses around obstacle belts or to determine the best locations and methods for breaching operations.

• Reconnaissance by infantry patrols of choke points or other danger areas in advance of the remainder of the company.

• Reconnaissance by mounted patrols to observe forward positions or to clear a route to a forward position.

• Reconnaissance of defensive positions or engagement areas prior to the conduct of the defense.

• Reconnaissance by mounted or dismounted patrols as part of security operations to secure friendly obstacles, clear possible enemy OPs, or cover areas not observable by stationary OPs.

7-2

FM 3-21.11

• Reconnaissance by mounted or dismounted patrols to maintain contact with adjacent units.

• Reconnaissance by mounted or dismounted patrols to maintain contact with enemy elements.

Figure 7-1. SBCT infantry company commander identifying intelligence requirements and using patrols to conduct reconnaissance.

7-3

FM 3-21.11

7-4. RECONNAISSANCE

DURING

OPERATIONS

During offensive operations, company reconnaissance normally focuses on fighting for information about the enemy and the terrain, with the primary goal of gaining an advantage over the enemy. The company conducts this type of reconnaissance during actions on contact. As the company develops the situation, the commander may dispatch mounted or dismounted patrols to identify positions of advantage or to acquire an enemy force. The information gained by the company while in contact is critical not only to the success of its own mission but also to the success of its higher headquarters. (Refer to Chapter 4 for discussion of actions on contact.)

7-5.

FORMS OF RECONNAISSANCE

In addition to reconnaissance performed as part of another type of operation, there are three forms of reconnaissance that are conducted as distinct operations: route reconnaissance, zone reconnaissance, and area reconnaissance.

a. Positioning of Subordinate Elements. In conducting a route, zone, or area reconnaissance, the company employs a combination of mounted and dismounted elements as well as reconnaissance by direct and indirect fires. Based on his evaluation of METT-TC factors, the company commander establishes the role of organic elements and support assets within his scheme of maneuver.

b. Focus of the Reconnaissance. In planning for route, zone, or area reconnaissance, the company commander must determine the focus of the mission, identifying whether the reconnaissance will orient on the terrain or on the enemy force. It is then essential that he provide the company with clear guidance on the focus of the reconnaissance. In a force-oriented reconnaissance operation, the critical task is simply to find the enemy and gather information on him; terrain considerations of the route, zone, or area are only a secondary concern. The company is generally able to move more quickly in force-oriented reconnaissance than in terrain-oriented reconnaissance.

c. Conduct of the Reconnaissance. The following paragraphs examine the specifics of route, zone, and area reconnaissance:

(1) Route Reconnaissance. A route reconnaissance is a directed effort to obtain detailed information on a specific route as well as on all terrain from which the enemy could influence movement along that route. Route reconnaissance may be oriented on a specific area of movement, such as a road or trail, or on a more general area, like an axis of advance.

(2) Zone Reconnaissance. A zone reconnaissance is a directed effort to obtain detailed information concerning all routes, terrain, enemy forces, and obstacles (including areas of chemical and radiological contamination) within a zone that is defined by specific boundaries. The company normally conducts zone reconnaissance when the enemy situation is vague or when the company requires information concerning cross-country trafficability. As in route reconnaissance, the SBCT and SBCT infantry battalion commanders' intents as well as METT-TC dictate the company’s actions during a zone reconnaissance.

(a) The following tasks are normally critical components of the operation:

• Find and report all enemy forces within the zone.

• Reconnoiter specific terrain within the zone.

• Report all reconnaissance information.

7-4

FM 3-21.11

(b) Time permitting, the commander may also direct the company to accomplish the following tasks as part of a zone reconnaissance:

• Reconnoiter all terrain within the zone.

• Inspect and classify all bridges.

• Locate fords or crossing sites near all bridges.

• Inspect and classify all overpasses, underpasses, and culverts.

• Locate and clear all mines, obstacles, and barriers (within capability).

• Locate bypasses around built-up areas, obstacles, and contaminated areas.

(3) Area Reconnaissance. Area reconnaissance is a directed effort to obtain detailed information concerning the terrain or enemy activity within a prescribed area. The area can be any location that is critical to the unit’s operations. Examples include easily identifiable areas covering a fairly large space (such as towns or military installations), terrain features (such as ridge lines, wood lines, or choke points), or a single point (such as a bridge or a building). The critical tasks of the area reconnaissance are the same as those associated with zone reconnaissance.

Section II. LINKUP

Linkup is an operation that entails the meeting of friendly ground forces (or their leaders or designated representatives). The company conducts linkup activities independently or as part of a larger force. Within a larger unit, the company may lead the linkup force.

7-6. LINKUP

SITUATIONS

Linkup may occur in, but is not limited to, the following situations:

• Advancing forces reaching an objective area previously secured by air assault, airborne, or infiltrating forces.

• Units conducting coordination for a relief in place.

• Cross-attached units moving to join their new organization.

• A unit moving forward during a follow and support mission with a fixing force.

• A unit moving to assist an encircled force.

• Units converging on the same objective during the attack.

• Units conducting a passage of lines.

7-7. LINKUP

PLANNING

The plans for a linkup must be detailed and must cover the following items: a. Site Selection. Identify both a primary and an alternate site. These sites should be easy to find at night, have cover and concealment, and be off the natural lines of drift.

They must also be easy to defend for a short time and offer access and escape routes.

b. Recognition Signals. Far and near recognition signals are needed to keep friendly units from firing on each other. Although the units conducting the linkup exchange radio frequencies and call signs, they should avoid radio communications as a means of recognition due to the threat of compromise. Instead, visual and voice recognition signals should be planned:

(1) One technique is a sign and countersign exchanged between units. This can be a challenge and password or a number combination for a near signal. It can also be an exchange of signals using flashlights, chemical lights, infrared lights, or VS-17 panels for far recognition signals per tactical SOPs.

7-5

FM 3-21.11

(2) Another technique is to place other signals on the linkup site. Examples are stones placed in a prearranged pattern, markings on trees, and arrangements of wood or tree limbs. These mark the exact location of the linkup. The first unit to the linkup site places the sign and positions the contact company to watch it. The next unit to the site then stops at the signal and initiates the far recognition signal.

c. Indirect Fires. Indirect fires are always planned. They support the movement by masking noise, deceiving the enemy of friendly intent, and distracting the enemy. Plan indirect fires along the infiltration lanes and at the linkup sites to support in case of enemy contact.

d. Direct Fires. Direct fire planning must prevent fratricide. Restrictive fire lines (RFLs) control fires around the linkup site. Phase lines may serve as RFLs, which are adjusted as two forces approach each other.

e. Contingency Plans. The unit tactical SOP or the linkup annex to the OPORD

must cover the following contingencies:

• Enemy contact before linkup.

• Enemy contact during linkup.

• Enemy contact after linkup.

• How long to wait at the linkup site.

• What to do if some elements do not make it to the linkup.

• Alternate linkup points and rally points.

7-8.

STEPS OF THE LINKUP OPERATION

The linkup procedure begins as the unit moves to the linkup point. If using the radio, the unit reports its location using phase lines, checkpoints, or other control measures. Each unit sends a small contact team or element to the linkup point; the remainder of the unit stays in the linkup rally point. The leader fixes individual duties of the contact elements and coordinates procedures for integrating the linkup units into a single linkup rally point.

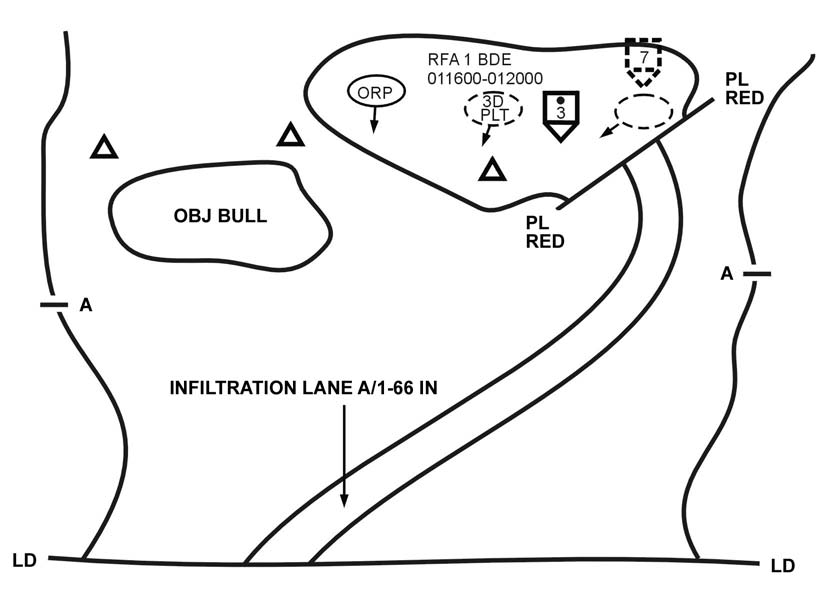

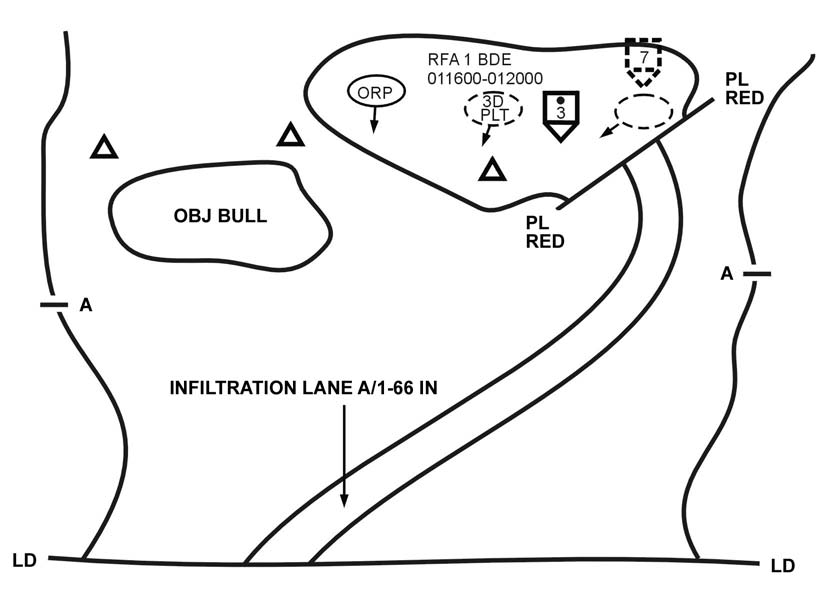

Full rehearsals are conducted if time permits. Figure 7-2 depicts a company linkup between the 3d Platoon--which infiltrated early, conducted the reconnaissance of the objective, and established the ORP--and the rest of the company, which infiltrated later.

7-6

FM 3-21.11

Figure 7-2. SBCT infantry company linkup.

a. The unit stops and sets up a linkup rally point about 300 meters from the linkup point. A contact team is sent to the linkup point; it locates the point and observes the area.

If the unit is the first at the site, it clears the immediate area and marks the linkup point, using the agreed-upon recognition signal. It then takes up a covered and concealed position to watch the linkup point.

b. The next unit approaching the site repeats the actions above. When its contact team arrives at the site and spots the recognition signal, they then initiate the far recognition signal, which is answered by the first company, and they exchange near recognition signals.

c. The contact teams coordinate the actions required to link up the units, such as to move one unit to the other unit's rally point, or to continue the mission.

d. The linkup consists of three steps:

(1) Far Recognition Signal. During this step, the units or elements involved in the linkup should establish communications before they reach direct fire range, if possible.

The lead element of each linkup force should operate on the same frequency as the other friendly force.

(2) Coordination. Before initiating movement to the linkup point, the forces must coordinate necessary tactical information, including the following:

• The known enemy situation.

• Number and types of friendly vehicles.

• Disposition of stationary forces (if either unit is stationary).

• Routes to the linkup point and rally point (if used).

• Fire control measures.

7-7

FM 3-21.11

• Near recognition signal(s).

• Communications information.

• CS coverage.

• CSS responsibilities and procedures.

• Finalized location of the linkup point and rally point (if used).

• Any special coordination, such as that covering maneuver instructions or requests for medical support.

(3) Movement to the Linkup Point and Linkup. All units or elements involved in the linkup must enforce strict fire control measures to help prevent fratricide; linkup points and RFLs must be easily recognizable by moving and converging forces. Linkup elements take these actions:

• Conduct far recognition using FM radio.

• Conduct short-range (near) recognition using the designated signal.

• Complete movement to the linkup point.

• Establish local security at the linkup point.

• Conduct additional coordination and linkup activities as necessary.

Section III. SECURITY OPERATIONS

The company may conduct security operations to the front, flanks, or rear of the SBCT

force. Security operations provide early and accurate warning of enemy operations and provide the protected force with time and maneuver space to react to the enemy and develop the situation so that the commander can employ the protected force effectively.

(For additional information on security operations, refer to FM 17-95.) 7-9.

FORMS OF SECURITY OPERATIONS

The four forms of security operations are screen, guard, covering force, and area security.

Screen, guard, and cover entail deployment of progressively higher levels of combat power and provide increasing levels of security for the main body. Area security preserves a higher commander’s freedom to move his reserves, position fire support assets, conduct command and control operations, and provide for sustainment operations.

The company can conduct screen or guard operations on its own. It participates in area security missions and covering force operations only as part of a larger element. The company always provides its own local security.

NOTE: All forces have an inherent responsibility to provide for their own local security. Local security includes OPs, local security patrols, perimeter security, and other measures taken to provide close-in security for the force.

7-10. PLANNING

CONSIDERATIONS

Security operations require the commander assigning the security mission and the security force commander to address a variety of special operational factors. These planning considerations are discussed in the following paragraphs: a. Augmentation of Security Forces. When it is assigned to conduct a screen or guard mission, the company may receive additional combat, CS, and CSS elements.

Attachments may include, but are not limited to, the following:

7-8

FM 3-21.11

• A reconnaissance platoon.

• A mortar section or platoon.

• RSTA assets.

b. Enemy-Related Considerations. Security operations require the company to deal with a unique set of enemy considerations. For example, the array of enemy forces (and the tactics that enemy commanders use to employ them) may be different from those for any other tactical operation the company conducts. Additional enemy considerations that may influence company security operations include, but are not limited to, the following: (1) The presence or absence of specific types of forces on the battlefield including--

• Insurgent elements (not necessarily part of the enemy force).

• Enemy reconnaissance elements of varying strength and capabilities (at divisional, brigade, or other levels).

• Enemy security elements (such as forward patrols).

• Enemy stay-behind elements or enemy elements that have been bypassed.

(2) Possible locations that the enemy will use to employ his tactical assets including--

• Reconnaissance and infiltration routes.

• OP sites for surveillance or indirect fire observers.

(3) Availability and anticipated employment of other enemy assets including--

• Surveillance devices, such as radar devices or UAVs.

• Long-range rocket and artillery assets.

• Helicopter and fixed-wing air strikes.

• Elements capable of dismounted insertion or infiltration.

• Mechanized forward detachments.

c. Time the Security Operation is Initiated. The time by which the screen or guard must be set and active influences the company’s method of deploying to the security area as well as the time it begins the deployment.

d. Reconnaissance of the Security Area. The company commander uses a thorough analysis of METT-TC factors to determine the appropriate methods and techniques for the company to use in accomplishing this critical action.

NOTE: The company commander must make every effort to conduct his own reconnaissance of the security area he expects the company to occupy, even when the operation is preceded by a zone reconnaissance by other SBCT

battalion elements.

e. Movement to the Security Area. In deploying elements to an area for a stationary security mission, the company commander must deal with the competing requirements of establishing the security operation quickly to meet mission requirements and of providing the necessary level of local security in doing so. The company can move to the security area using one of two basic methods: a tactical road march or a movement to contact. Either method should be preceded by a zone reconnaissance by the SBCT infantry battalion reconnaissance platoon. The following paragraphs examine considerations and procedures for the two methods of movement.

(1) Tactical Road March. The company conducts a tactical road march to an RP

behind the security area to occupy their initial positions. This method of deployment is

7-9

FM 3-21.11

faster than a movement to contact, but less secure. It is appropriate when enemy contact is not expected or when time is critical.

(2) Movement to Contact. The company conducts a movement to contact from the LD to the security area. This method is slower than a tactical road march, but it is more secure. It is appropriate when time is not critical and either enemy contact is likely or the situation is unclear due to the company commander's lack of RSTA assets.

f. Location and Orientation of the Security Area. The main body commander determines the location, orientation, and depth of the security area in which he wants the security force to operate. The security force commander conducts a detailed analysis of the terrain in the security area. He then establishes his initial dispositions (usually a screen line, even for a guard mission) as far forward as possible, on terrain that allows clear observation of avenues of approach into a sector. The initial screen line is depicted as a phase line and sometimes represents the forward line of troops (FLOT). As such, the screen line may be a restrictive control measure for movement. This requires the company commander to conduct all necessary coordination if he decides to establish OPs or to perform reconnaissance forward of the line.

g. Initial OP Locations. The company commander may deploy OPs to ensure effective surveillance of the sector and designated NAIs. He designates initial OP

locations on or behind the screen line. He should provide OP personnel with specific orientation and observation guidance, including, at a minimum, the primary orientation for the surveillance effort during the conduct of the screen. Once set on the screen line, the surveillance elements report their locations. The element that occupies each OP

always retains the responsibility for changing the location in accordance with tactical requirements and the commander’s intent and guidance for orientation. Dismounted OPs maximize stealth.

h. Width and Depth of the Security Area. The company sector is defined by lateral boundaries extending out to an LOA (the initial screen line) forward of a rear boundary. The company’s ability to maintain depth through the sector decreases as the screened or guarded frontage increases.

i. Special Requirements and Constraints. The company commander must specify any additional considerations for the security operation, including, but not limited to, the following:

• All requirements for observing NAIs, as identified by the SBCT battalion.

• Any additional tactical tasks or missions that the company and subordinate elements must perform.

• Engagement and disengagement criteria for all company elements.

j. Indirect Fire Planning. The company commander conducts indirect fire planning to integrate artillery and mortar assets into the security mission. A wide sector may require him to position mortar assets where they can provide effective coverage of the enemy’s most likely axis of attack or infiltration route, as determined in his analysis of the enemy. The commander can position the mortars so that up to two thirds of their maximum range lies forward of the initial screen line. The company FSO assists the commander in planning artillery fires to adequately cover any gaps in mortar coverage.

k. Positioning of Command and Control and CSS Assets. The company commander normally positions himself where he can observe the most dangerous enemy axis of attack or infiltration route, with the XO positioned on the second most critical axis 7-10

FM 3-21.11

or route. The XO positions the company CP (if used) in depth and, normally, centered in sector. This allows the CP to provide control of initial movement, to receive reports from the screen or guard elements, and to assist the commander in more effectively facilitating command and control. Company trains are positioned behind masking terrain, but they remain close enough for rapid response. The trains are best sited along routes that afford good mobility laterally and in depth. Patrols may be required to cover gaps between the OPs. The company commander tasks elements to conduct either mounted or dismounted patrols, as required.

l. Coordination. The company commander must conduct adjacent unit coordination to ensure there are no gaps in the screen or guard and to ensure smooth execution of the company’s rearward passages of lines, if required. Additionally, he must coordinate the company’s follow-on mission.

m. CSS Considerations. The company commander’s primary consideration for CSS

during security operations is coordinating and conducting resupply of the company, especially for Class III and V supplies. (One technique is for the commander to pre-position Class III and Class V vehicles at the company’s successive positions.) In addition to normal considerations, however, the commander may acquire other responsibilities in this area, such as arranging CSS for a large number of attached elements or coordinating resupply for a subsequent mission. The company’s support planning can be further complicated by a variety of factors. To prevent these factors from creating outright tactical problems, the company must receive requested logistical support, such as additional medical evacuation vehicles, from the controlling SBCT

battalion.

n. Follow-On Missions. The complexities of security missions, combined with normal operational requirements (such as troop-leading procedures or on-the-move

[OTM] planning, engagement area development, rest plans, and CSS activities), can easily rob the company commander of the time he needs for planning and preparation of follow-on missions. H