CHAPTER VIII

ON THE EXTINCTION OF THE MASTODON

The recent visit of King Ptush to our wild districts in search of a fresh hunting-ground for himself and his son, Prince Ptutt, brought about a very serious condition of affairs in respect to the mastodon, or what some persons refer to as the Antediluvians. This most distinguished personage, wearying of the affairs of state in his own land, gave over the reins of government for a while to his Grand Vizier, and on behalf of the Nimrodian Institution, a Museum of Natural and Unnatural History in his own capital city, came hither to study the fauna and flora of our district, and incidentally to take back with him a variety of stuffed specimens of our more conspicuous wild beasts for exhibition purposes. Entirely unaware of His Majesty's unerring aim in hitting large surfaces at short range, we welcomed him cordially to our midst, and rather unwisely presented him with the freedom of the jungle, a ceremony which carried with it the privilege of bagging anything he could hit with his slungshot, in season or out of it. The results of His Majesty's visit were appalling, for he had not been with us more than six weeks before his enthusiasm getting the better of his sportsmanship he turned the jungle into a zoological shambles, from which it is never likely to recover. On his first day's outing, to our dismay he brought down thirty-seven ring-tailed ornithorhyncusses, eighteen pterodactyls, three brace of dodo, and a domesticated diplodocus, and then assured us that he didn't know what could be the matter with his aim that he had missed so many.

The next day he rose early, and while the rest of his suite were sleeping went out unattended, returning before breakfast was over with a tally-card showing a killing of thirteen dinosaurs, twenty-seven megatheriums, and about six tons of chlamy-dophori, not to mention a mammoth jack-rabbit that some idiot had told him was the only specimen in the world of the monodelphian mollycoddle. The situation became very embarrassing to us because we were on excellent terms with King Ptush and his subjects, and we did not wish to do anything to offend either of them, but here was a case where in the interests of our own fauna something had to be done. Going on at the rate in which he had begun it was easy to see that unless somebody got out an injunction restraining him from shooting between meals it would not be many days before there wasn't a prehistoric beast left in the whole country. It was a mighty ticklish position for all of us. If we withdrew the freedom of the jungle His Majesty might go home in a huff and declare war against us, and with Noah's Ark as the sum total of our navy, and that built in a ten-acre lot thirty miles from the coast, and no army of any sort standing or sitting, we could hardly afford a complication of that kind. Our wisest counsellors were called together to consider the situation, but they were all men given to many words and lovers of disputation, so that what with the framing of the original resolution, and the time consumed in debating the amendments offered thereto, it was quite three months before any definite conclusion was reached, and it was then found when the resolution came up to its final vote that it had nothing whatever to do with the subject the conference was called to discuss, but had been transformed into an Act providing for an increased duty on guinea-pigs imported from Sumatra. From that day to this I have had little belief in that kind of popular government which provides for the election of public servants whose chief end and aim seems to be to thwart the public will.

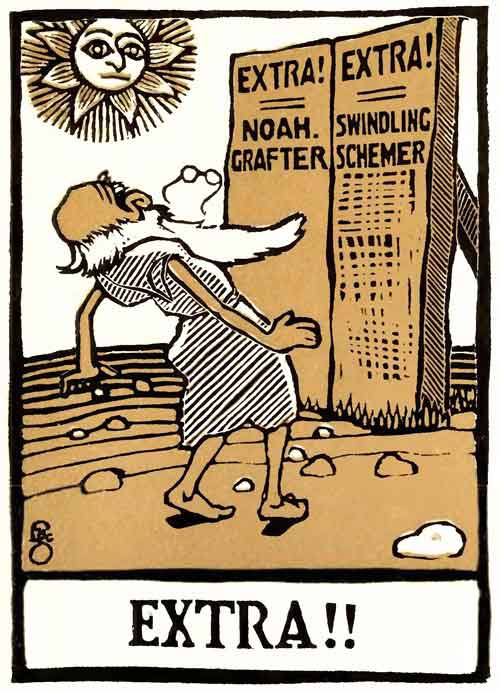

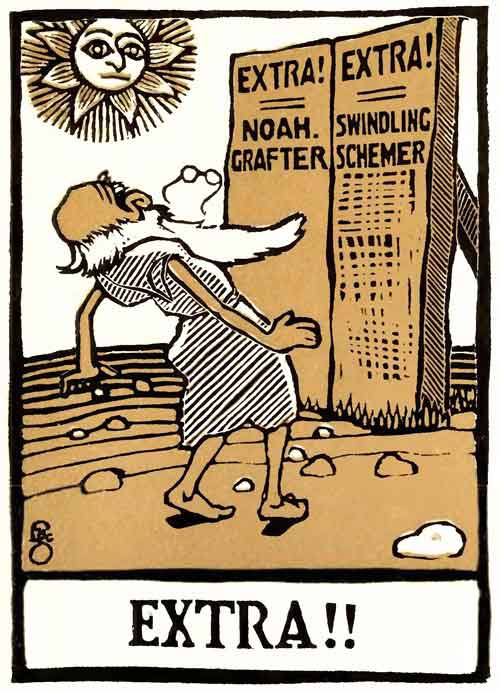

EXTRA!!

It was then that my fellow-citizens, availing themselves of a certain diplomacy of method which I was said to possess, called upon me to undertake a personal interview with King Ptush, and to see what could be done to stay his voracious appetite for the slaying of our mammalia. Always ready to serve my fellows in their hour of need, I undertook the mission, and appeared bright and early one morning at his encampment, unannounced, thinking it better to seem to happen in upon him in a neighborly fashion than to make a national affair of my mission by coming formally and with official pomp into his presence. At the hour of my arrival the great king was standing on the stump of a red cedar, delivering a lecture to his entourage upon "The Whole Duty of Man, With a Few Remarks About Everything Else." But even then he was not neglectful of his opportunities as a Nimrod, for every now and then he would punctuate his sentences with a shot at a casual bit of fauna passing by, either on the earth or flying, never pausing in his lecture, but nevertheless bringing to an untimely end thirty-eight griffins, seven paralellopipedon, a gumshurhynicus, forty google-eyed plutocratidæ, and a herd of June-bugs grazing in a neighboring pasture—the latter wholly domesticated, by the way, and used by their owner as spile-drivers for a dike he was building in apprehension of Noah's predicted flood. It was then that I began to get some insight into the character of this wonderful person, for as I sat there listening to his discourse, delivered at the rate of five hundred words a minute, and apparently covering seven or eight subjects not necessarily corollary or collateral to each other, at once, and watched him simultaneously bringing down with unerring aim this tremendous bag of game, something of the man's intrinsic nature was revealed to me. His strength, of which we had heard much from travelers in his own land, lay in an almost scientific lack of concentration, backed up by a vocabulary of tremendous scope, and a condition of optical near-sightedness that enabled him to see but obscurely further than the end of his nose. These attributes gave him the power to discuss innumerable subjects coeternally, if not coherently, using his vocabulary with such skill that his meaning depended entirely upon the interpretation of his remarks by individual hearers, while the limitations of vision caused him, on the sudden appearance of masses of any sort, to shoot at them impulsively, regardless of such minor details as consequences. As a result of these gifts he was ever hitting something with either the arrows of speech or the slungshot, which produced a public impression of ceaseless activity and of material accomplishment. In addition to this it was his wont to do all things smiling with an almost boyish manifestation of pleasure, so that he endeared himself to the people and was pronounced in some respects likeable even by his enemies.

When his lecture was over he descended from his improvised platform and greeted me most cordially.

"Deeee-lighted!" was the exact word he used as he took my hand and shook it until my arm worked indifferently well in its socket.

I was not aware that His Highness had ever heard of me before, but it was not long before I was more than glad that I had come, for it transpired that I was the one person in all creation that he had most wished to meet, though for what particular purpose he did not make clear. In any event, so cordial was his reception of me that for three or four weeks I had not the heart to mention the particular object of my mission, and even then I was not permitted to do so because at any time when I felt that the psychological moment had been reached he would talk of other things, his scientific lack of concentration of which I have already spoken enabling him with much grace to be reminded of an experience in the Transvaal by a chance allusion of my own to the peculiar habits of the Antillean Sardine. In the meanwhile the work of slaughter was going on apace, and whole species were gradually becoming extinct. Exactly five weeks after my arrival the last Diplodocus in the world breathed its last. Two days later the world's visible supply of Pterodactyls passed into the realms of the annihilated. The Dodo, the largest and sweetest song-bird I have ever known, the only bird in all the primeval forests possessed of a diaphragm capable of expressing harmonies of what for want of a better term I may call a Wagnerian range, quickly followed suit, and in its train, alas! went the others, Creosauri, Dicosauri, Thracheotomi, Megacheropodæ, Manicuridæ, and the Willumjay, the latter a gigantic parrot with a voice like silver that rang continuously through the forests like a huge fire bell. At the end of the tenth week of my mission a message was received from Noah.

"Dear Grandpa," he wrote: "Can't you do something to stave off King Ptush? In making up my passenger-list I can't get hold of enough mammals to fill an inside room. I have been through the country with a fine-tooth comb, and as far as I can find out there isn't a prehistoric beast left in creation.

If this thing goes on much longer I shall be compelled to load up with a cargo of coon-cats, armadillos, hippopotami and Plymouth rocks. Get a move on!

"Noah."

My first impulse was to hand this letter without a word to His Majesty, but on second thoughts I decided not to do this, since it might involve me in a humiliating explanation of my grandson's foolish obsession about the impending flood. I had too much pride to wish King Ptush to know that I had a human brain-storm on the list of my posterity, so I threw the brick upon which the letter was engraved into a neighboring fish-pond, and resolved to get rid of His Majesty by strategy. For three nights I pondered over my plan of operations, and then the great method came to me like the dawning of the sun after a night of abysmal darkness. I went to the royal tent and discovered His Majesty hard at work chiseling out an article on "How I Brought Down My First Proterosaurus" on a slab of granite he had brought with him. As I approached he smiled broadly, and with a wave of his hand called my attention to the previous day's bag. It covered a ten-acre lot.

"There isn't sawdust enough in creation to stuff half of these beasts," he remarked proudly. "I hardly know what I shall do about that."

"Better bury them in the mud," I suggested, "and let them petrify."

He seemed pleased with the idea, and later put it into operation.

"Fossils are not so susceptible to moths," he observed as he gave orders for their immersion in a Triassic mud-puddle of huge proportions. "That was a good idea of yours, Methuselah."

"I have a better one than that," I returned, seeing at last an opening for my strategic movement. "Why should a man of Your Majesty's prowess waste his time on such insignificant creatures as these, when the whole country is ringing with complaints of an animal a thousand times as large, and that no one hereabouts has ever dared attempt to pursue?"

He was on the alert instantly.

"What animal do you refer to?" he demanded, his interest becoming so deep that he put four pairs of eyeglasses upon his royal nose, so that he could see me better.

"It belongs to the family of Rodents," I replied. "It is without any exception the biggest rat in the history of our mammals. It is a combination of the Castoridæ, the Chinchillidæ, the Dodgastidæ, and the Lagomydian Leporidæ, with just a dash of the Dippydoodle on the maternal side."

His Majesty gave a sigh of disappointment, and resumed his writing.

"I haven't come here to shoot rats," he observed coldly, removing the three extra pairs of spectacles from his nose. "I am a huntsman, not a trapper."

"Your Majesty does not understand that this is no ordinary rat," I returned calmly. "If I may be permitted to continue, what would Your Highness think of a rat that was several thousand feet higher than the pyramids, that has lived continuously for thousands of years, and is as fresh and green in spirit as on the day it was born? Suppose I were to tell you that so great is its strength that I have myself seen a whole herd of aboriginal elephants lying asleep upon its broad back? What would you say if I told you that its epidermis is so thick that if there were such a thing as a steam-drill in creation six hundred of them could bore away at it night and day for as many years without making any visible impression thereon?"

He again put down his chisel, and laid the hammer aside, as he ranged the extra eyeglasses along the bridge of his nose.

"Colonel Methuselah," he said, incisively biting off his words, "if you told me anything of the kind I should say that you are what posterity will probably call a nature faker, and one of a perniciously invidious sort."

"I can bring affidavits to prove it, Your Majesty," said I.

"It is strange that I have never heard of it before," he mused.

"We are not particularly proud of it," I explained. "One may boast of the number of Discosauri one finds in one's hunting preserves, or the marvelous fish in one's lakes, or the birds of wondrous plumage that dwell in one's forests, but none ever ventures to speak of the number or quality of rats that infest the locality."

"You say it overtops a pyramid?" he demanded.

"I do," I replied. "The exact estimate of its height is sixteen thousand nine hundred and sixty-four feet!"

"Great Snakes!" he cried. "Why, he must be a perfect mountain!"

"He is," I replied. "He is so tall that summer and winter the top of his head is covered with snow."

This was too much for King Ptush. He rose up immediately from his seat and summoned his entourage.

"You will make ready for a strenuous afternoon," he said to them sharply. "I am going after the biggest game that history records. Colonel Methuselah has just told me of a quarry alongside of which all that we have landed in the past months sinks into insignificance."

"You do well to call it a quarry," I cried. "There never was a better—and it is only ten miles from here as the griffin flies."

The king's face flushed with joy at the prospect, but suddenly a look of perplexity came into his eyes.

"By the way," he said, "how shall we bring him down—with a slungshot or a catapult?"

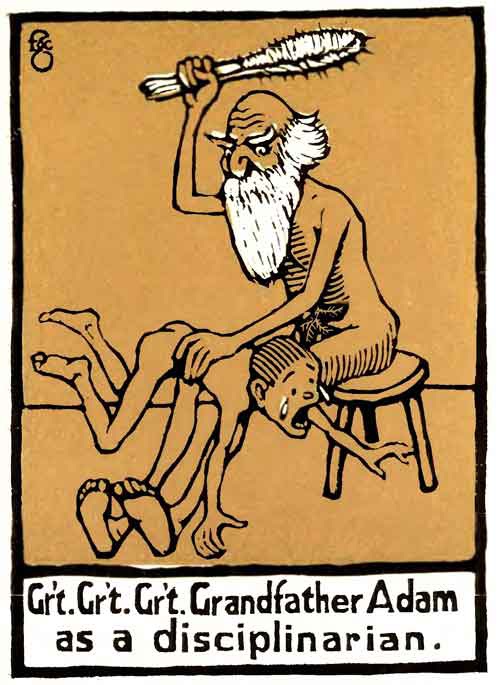

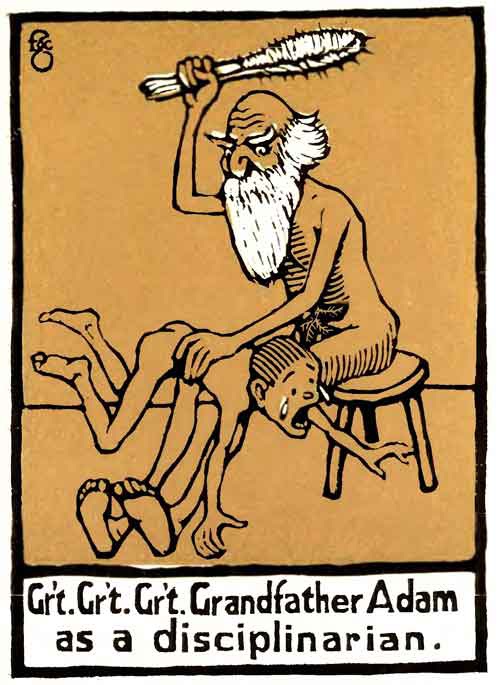

Gr't. Gr't. Gr't. Grandfather Adam as a disciplinarian.

I laughed.

"No ordinary ammunition will serve Your Majesty's purpose here," I said. "The only thing for you to do is to steal quietly up to him while he sleeps. Surround him in the silence of some black night, and build a barbed-wire fence around him.

Once you succeed in doing this he will not try to get away, and you can have him removed at Your Majesty's pleasure."

"We go at once," cried the king, his enthusiasm aroused to the highest pitch. "My friends," he added, drawing himself up to the full of his soldierly height, "we go to capture the—the—the er—by the way, Colonel, what do you call this creature?"

"The Ararat," I replied.

He repeated the word after me, sprang lightly into the saddle of Griffin we had presented to him upon his arrival, and, followed by his entourage, was off on the greatest hunt of his life. What happened subsequently we never knew, for none of the party ever returned; but what I do know is that my stratagem came too late.

A subsequent investigation of our preserves showed that all our treasured mastodons from the Jurassic, Triassic, and other periods of history, had been killed off, root, stock and branch, by our honored guest, and poor Noah was reduced to the necessity of drumming up trade among such commonplace creatures as the Rhinoceri, the Yak, the Dromedary, and that vain but ornamental combination of fuss and feathers known as the Hen.

The Ararat we still have with us, and as for me, I am inclined to think that it will remain, flood or no flood, for any creature that has successfully withstood a campaign against it by King Ptush cannot be removed from the scene by anything short of a convulsion of Nature.