CHAPTER III

Converging Streams

In a systematic presentation of the evidences in the field of Christian apologetics, it is necessary to review the Egyptian and Chaldean records as they bear upon the text of the Scripture, and illumine its meaning. For it is here that the streams of History and Revelation converge, to continue their flow in mingled harmony throughout all the centuries which follow this original conjunction.

In the very nature of the case we would not expect direct archeological confirmation of a great deal of the earlier portions of the Old Testament. The record of creation which was handed down from Adam to each generation delineated an event which was not witnessed by any human being. As has been very clearly shown in the illuminating book, “New Discoveries in Babylonia about Genesis,” by P. J. Wiseman, this record was undoubtedly preserved in a written form from the very time of Adam himself.

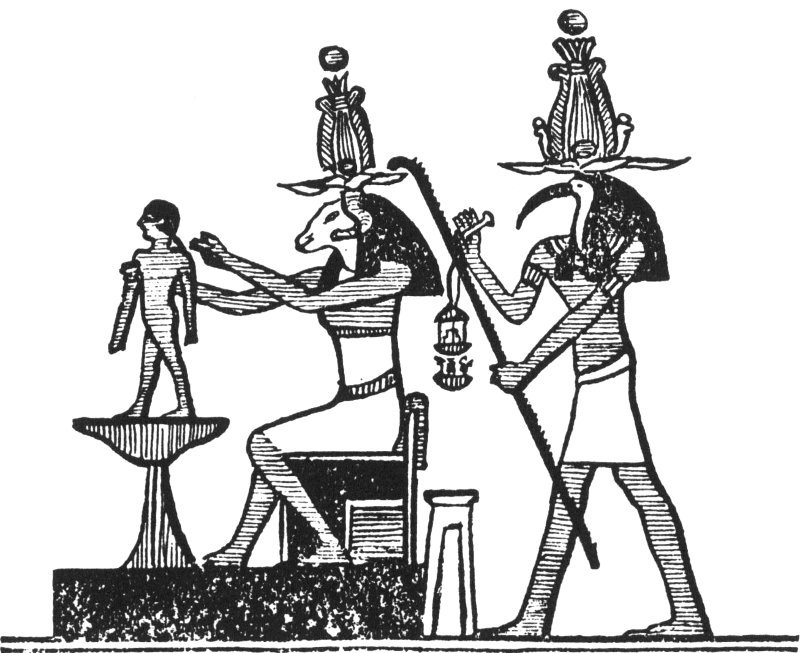

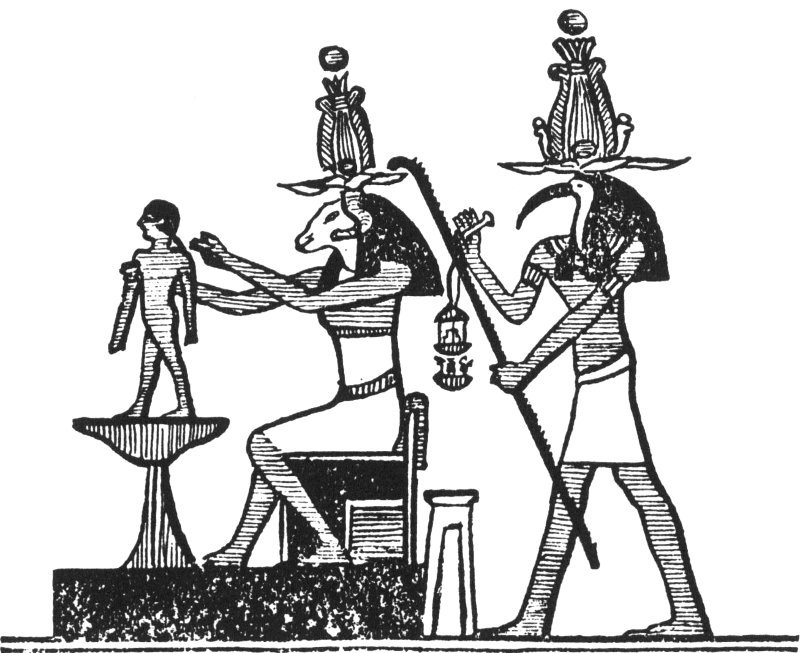

Khnum and Thoth in Creation Tradition.

The events of the Garden of Eden and the subsequent history are not such as would leave archeological material for the exact enlightenment of later generations. There is, however, a manner in which the study of antiquity can bring a tremendous light to shine upon the dark problem of the credibility of these records. It is generally conceded by ethnologists that when races of people hold a strongly developed idea or belief, in common, there must have been an historical incident as the basis of that universal tradition. Thus, among the very earliest traditions of ancient Egypt, there is a record of the creation of man that bears a valuable relationship to the account in Genesis.

The Mosaic record states that God stooped and created the body of man out of the dust of the earth. Life was imparted to that body by the very breath of God.

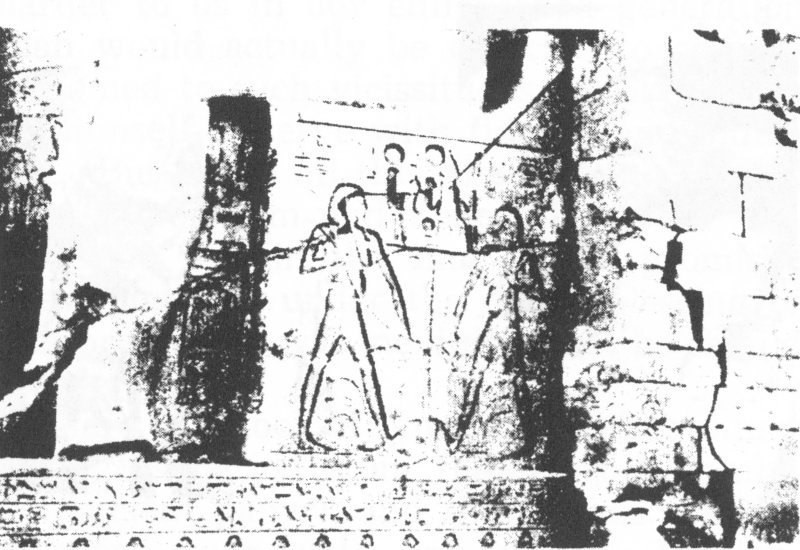

The earliest Egyptian record recounts how the god Khnum took a slab of mud, and placing it upon his potter’s wheel, moulded it into the physical form of the first man. The illustration facing this page shows the entire process, with Thoth standing behind Khnum, and marking the span of man’s years upon a notched branch. Here then is a coincidence of traditional belief in the manner of creation of man that is of tremendous significance.

We also note that the earliest records of Sumeria have this same incidental bearing upon certain portions of the Old Testament text.

All of the records of antiquity begin the history of man in a garden. This is of considerable significance in view of the account of Eden that is so prominently given in the record of Genesis.

Among the seals to which we shall occasionally refer and which are shown in Plate 8, there is one from an early period in Sumeria from which we have derived considerable understanding of Sumerian beliefs. This seal shows Adam and Eve on opposite sides of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and can be nothing less than a direct reference to the event that is recorded in the Book of Genesis.

One of the most constantly cited documents of antiquity, is the so-called Gilgamesh epic. The high antiquity of the original form in which this occurs may be seen from the fact that many of the seals that go as far back as the year 3,000 B. C. are made of illustrations of the various episodes that are contained in this valuable document. The original home of Gilgamesh seems to have been at Erech. The city was evidently besieged by an army led by Gilgamesh, who, after a three-year war, became the king of the city. So harsh was the despotic rule of the conquering monarch that the people petitioned the goddess Aruru to create a being strong enough to overthrow Gilgamesh and release them from his sway.

Some of the gods joined in with this prayer and as a result a mythical being, partly divine, partly human, and partly animal, was created and dispatched to Erech for the destruction of Gilgamesh. This composite hero bears a great many different names, but the earliest accepted form in the Babylonian account was Enkedu. Gilgamesh, learning that an enemy had been created for his destruction, exercised craft and lured Enkedu to the city of Erech. The two became fast friends and set out finally to do battle with a mighty giant named Khumbaba. When they arrived at his castle, they besieged and captured the stronghold of the giant, whom they slew. They carried off his head as a trophy and returned to Erech to celebrate their victory.

The plan of the gods being thus frustrated, the goddess Ishtar besought her father Anu to create a mighty bull to destroy Gilgamesh. The bull being formed and dispatched upon its duty, also failed of its purpose when Enkedu and Gilgamesh vanquished the animal after a tremendous battle. And so on, the story goes with episode after episode, culminating with a crisis in the account of the deluge.

In this climax, in a notable and fascinating manner, we see again the coincidence of tradition with a record of the Scripture. In the Babylonian account of the deluge, every major premise of the Mosaic record is sustained in its entirety. The Gilgamesh account tells of the heavenly warning, it depicts the gathering of material and the building of an ark. In the ark was safely carried the hero, his wife and his family with certain beasts of the earth for seed. The ark of the Gilgamesh episode was made water tight with bitumen exactly as was the ark of Noah in the record in the Book of Genesis. Entering this ark, the Babylonian account tells how the boat came under the direct supervision of the gods. On the same night a mighty torrent fell out of the skies. The cloudburst continued for six days and nights, until the tops of the mountains were covered. The sea arose out of its banks and helped to overflow the land. After the seventh day, the storm abated and the sea decreased. By that time, however, the whole human race had been destroyed with the exception of the little company who had been within the Babylonian ark.

The ark of Babylon grounded in that portion of the ancient world known as Armenia, the Hebrew name of which is Ararat. Seven days after the landing of the ark, the imprisoned remnant sent forth a dove. When she found no place to light and rest, the dove returned to the ship. They waited a short while and then sent forth a swallow. The swallow also returned, wearied from a long flight, and several more days were allowed to elapse. The next attempt to discover the condition of the earth by the imprisoned remnant resulted in the sending forth of a raven. The bird returned and approached the ark, but refused to re-enter the ship. The remnant knew then that the flood was ended. They accordingly went forth with all the redeemed life, and celebrated their preservation by offering up sacrifices to the gods upon the mountains.

The goddess Ishtar was so pleased with the sacrifice of the godly remnant that she hung in the heavens a great bow, which Anu, the father of the gods, had made for the occasion. She swore by the sacred ornaments that hung about her neck that mankind should not again be destroyed by a flood, and this heavenly bow was the sign of that covenant.

The incidental details which are found in this hoary manuscript coincide too closely with the record of Genesis to admit of coincidence. Archeology has brought no stronger testimony to the historicity of the Mosaic record of the deluge than this great account in the Gilgamesh epic, although interspersed with mythological characters and deviating from the simplicity of the Genesis account.

One of the most valuable publications of the British Museum is their monograph on the Gilgamesh legend, which contains a fine and scholarly translation of the deluge tablet in an unabridged form. Our own copy of this publication has been of great value to many students who have sought its aid in their detailed studies of the Old Testament.

Another one of the disputed portions of the Old Testament text which brought great comfort to the habitually hopeful among the destructive critics, is that section of Genesis which deals with the record of Nimrod and the tower of Babel.

Modern archeology not only has failed to bring any aid to the critics in this particular incident, but has robbed them of all their carefully erected structure of argument which was predicated upon the assumption that the tower of Babel was entirely mythological. Among the recent excavations in Mesopotamia was the work in the region which bore the oriental name of Birs-nimroud. When the excavators had finished their enormous task, they had laid bare a magnificent ziggurat of tremendous antiquity which was the largest so far discovered. At the time these ruins were first seen, this enormous tower covered an area of 1,444,000 square feet. It towered to the height of a bit more than 700 feet. Time has, of course, ravished this monument to some extent, but enough of its grandeur and glory remains to show it forth as the most ancient as well as the most magnificent of the Babylonian ziggurats.

According to the description given by Herodotus, in the middle of the fifth century, B. C., the structure then consisted of a series of eight ascending towers, each one recessed in the modern fashion of cutting-back that is used in certain types of sky-scraper architecture. The famous Step Pyramid at Sakkara is another ancient example of this type of structure, each successive and higher tower being smaller than the one upon which it rests. A spiral roadway, according to Herodotus, went around the entire ziggurat, mounting rapidly from level to level. He states that at each level a resting place was provided in this spiral roadway. At the top of the structure was a magnificent temple in which the religious exercises of the day were observed.

That this was the tower of Nimrod is generally accepted by the authorities of our present day. The name of Nimrod which in the Sumerian ideographs is read “Ni-mir-rud” is found on a number of artifacts and records of high antiquity, and reference is made as well to the great monument that he built.

So as we read our way through the episodes which constitute the earlier records of Genesis, we also dig our way into the older strata of humanity and find ourselves walking hand in hand with the twins of revelation and scientific vindication! They coincide in all their utterances, teaching us that all that the Word of God has to say to men may be accepted without question or doubt.

The late Melvin Grove Kyle has written extensively of his own researches at Sodom and Gomorrah, so that it is unnecessary to recapitulate the results of his lifetime of labor. The sulphurous overburden and the startling confirmation of the Book of Genesis derived from the work of Dr. Kyle and his associates would vindicate the Scriptural claims to historical accuracy even if they stood by themselves.

In the general argument and discussion that long has clustered about the record of Abraham, the starting point of critical refutation has generally been the fourteenth chapter of Genesis. It is stated that the battle of the kings that occurred in this disputed portion of Holy Writ, was in the days of Amraphel, king of Shinar. Since a contemporary is named as Ched-or-la-o-mer, a storm of argument has swept over and about that one opening verse of this important chapter. The allies of Ched-or-la-o-mer are well known from his own records, and Amraphel was not to be found among them. It was a tremendous blow to criticism when the discovery was made that Amraphel is the Hebrew name of the Sumerian form, Khammurabi.

Plate 3

Colossi of Karnak

Colossi of Luxor

Plate 4

Colossi of Amen-Hetep III guarding Valley of the Kings

At tomb of Tutanhkamen, in the Valley of Kings

The brilliant ability of this mighty ruler is one of the high points of far antiquity. The king-lists of antiquity, derived from many sources, were compiled by order of several of the kings of Assyria and constitute another of the many valuable records to be found in the British Museum. A recent publication of the Museum entitled “The Annals of the Kings of Assyria” is well worth many times the price of one pound sterling which is demanded for the volume. This scholarly and brilliant piece of work contains the original Assyrian text transliterated and translated with historical data that the careful scholar cannot be without. It settles the question of Khammurabi. This Khammurabi, whom we shall now call by his Hebrew name Amraphel, has left us a long series of tablets, monuments, letters, and a code of laws which stands engraved upon a great monument preserved also in the British Museum.

It is a long way back to that twentieth century before Christ, but neither time nor distance prevents our hearing the clamoring voices of men long dead, who shout to us their vindication of the nature, character, and integrity of these testimonies which are the Word of God!

It is a matter of common knowledge in our day that the word, or name, pharaoh, may be applied either to a person or to an office. Exactly as our modern word “president” may be applied to the function of the office, or to the possessor of it in person, so the ruler of Egypt could be known simply as The Pharaoh, or shorter still, as Pharaoh. As every president, emperor or king, however, has his own proper name, so each pharaoh also is designated by his personal name. Fortunately for our purpose, many pharaohs are mentioned in the pages of Holy Writ under the clear identification of their proper names. Many of them, however, are not identified by their personal name but are referred to only by the title of their kingly office. Thus, for instance, the pharaoh of the Exodus is not named personally in the text. Such attempts at identification of this pharaoh as are made, must be made from external sources. However, there can be no question of the identity of the rulers of Egypt, who are specifically named in the Word of God. Such men as the Pharaoh Shishak, the Pharaoh Zera and the Pharaoh So, are identified beyond any possibility of question.

It is a happy circumstance for the student of apologetics that each of the pharaohs who is so named in person by the writers of the Bible, has been discovered and identified in the records of archeology. No more emphatic voice as to the credibility and the infallible nature of the historical sections of the Scripture can be heard than that which is formed by the chorus of these pharaohs.

To note the background of this record, may we remind the reader that in early times, Egypt was a divided kingdom. It was known as Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, and a separate monarch reigned over each section. It happens that in the period of the divided kingdom, there were fourteen dynasties in each section of the land. The Egyptian, like all Eastern people, highly prized ancestral antiquity. The farther back into antiquity a man’s family could be traced in his genealogy, the more the honour that accrued to him. We are not without modern counterparts, even in our present democracy.

Therefore, when the two kingdoms were united, the first kings of the united kingdom added together the fourteen dynasties of Upper and Lower Egypt, making them consecutive instead of contiguous. Thus they built a spurious antiquity of twenty-eight dynasties to enhance their greatness.

The earlier archeologists fell into this trap, and consequently erected an antiquity phantom which obscured the problem of chronology for some considerable time. When it was discovered that these dynasties were concurrent, a great deal of the fallacious antiquity of Egypt was abandoned. This fictional antiquity, which doubled the factor of time for that period, had been used to discredit the text of the Bible by the critical scholars, so-called. Now, in the light of our present learning, we find no discrepancy between the antiquity of Egypt, properly understood, and the chronology of the Scripture, when it is divorced from the errors of Ussher. Incidentally, the chronology and antiquity demands of both archeology and revelation coincide beautifully with the demands of sane anthropology.

To delineate this background so necessary to the proper understanding of the record of the pharaohs, it is necessary to introduce the first occasion of the coincidence of the text of the Scripture with the land and the people of Egypt, as it is here that the streams of revelation and history begin to converge. This beginning is made, of course, in the flight of Abraham into Egypt at the time of a disastrous famine. Overlooking for the moment the reprehensible conduct of Abraham concerning the denial of his wife Sarah, and the consequent embarrassment of the pharaoh, we digress to make a brief survey of the incidents that lead up to the kindness of Pharaoh to Abraham.

There had been previous Semitic invasions of Egypt. The first reason for these forays, of course, was famine. Due to the unfailing inundation by the river Nile, the fertile land of Egypt was a natural storehouse. The land of Egypt is fertile, the sun is benevolent, and wherever water reaches the land, amazingly prodigious crops are the inevitable result. So in the ancient days, whenever there was drought in the desert countries surrounding Egypt, the hungry hordes looked on the food supplies of their neighboring country, and, naturally, moved in that direction. Thus the pressure of want was the primary reason for these early Semitic invasions.

The secondary cause was conquest. These people of antiquity were brutal pragmatists, as are certain nations in our present Twentieth Century. The theme song of antiquity undoubtedly was, “I came, I saw, I conquered.” The motive for living in those stern days seems to have been, “He takes who can, and keeps who may.”

The activating motive of much past history is simply spoils. Here now is a case in point. A family of kings ruled in Syria, who counted their wealth by flocks and herds. Driven by a combination of circumstances, they descended upon Egypt. They were pressed by the lack of forage in their own land, due to the drought, and they also lusted after the treasure and wealth of the neighboring country. So, without need for any other excuse, they descended with their armed hordes and conquered Egypt. There they ruled, established a dynasty and possessed the land for themselves. Since their principal possessions were their flocks and herds, they were known as the Shepherd Kings. They have come down in history as the Hyksos Dynasty. They unified Syria and Egypt, and it is intriguing to study the development of this unification as that process is seen in the pottery of that period. The work of Egyptian artisans began to take on certain characteristics of Syrian culture until, finally, the characteristic Egyptian line and decoration disappeared and the pottery became purely Syrian. The Shepherd Kings established commerce between the two halves of their empire and prosperity followed their conquest. These kings imported artists from their native Syria, together with musicians and dancers innumerable.

This intrusion of a foreign culture so changed the standards of Egypt that for generations the ideal of beauty was a Syrian ideal. Later, when the Syrian kings were expelled by Tahutmas the 2nd, the situation was reversed and Egypt, now governed by an Egyptian, kept Syria as her share of the spoils.

Four hundred years later another Semitic invasion swept over the land from Ur. It is quite probable that these conquerors were Sumerians. They established the sixteenth dynasty and brought with them also their treasure in the form of livestock. Thus, when Abraham entered Egypt, he found that it was ruled by his relatives! Thus we have an explanation of the cordial welcome that a Sumerian from Ur received from a pharaoh in Egypt. This contact is well established through the arts of that day, by pottery, by frescoes, and by means of the records of ancient customs. We know these things to be facts.

So when we read of the record of Abraham, we have at our disposal a vast and overwhelming source of evidence as to the credibility of this section of the record. The statements that are made in Genesis could have been written only by one who was intimately familiar with the Egypt of that day and time.

The second contact of Egypt and the Genesis record is found in the experience of Joseph. Although harsh and unkind, the action of the brothers in selling the youngest into slavery was perfectly legal under the code of that day. The younger brethren were all subject to the elders, and the law of primogeniture gave to the elder almost unlimited power over the life of the younger. The brutality and envy of this act are far from unparalleled in the secular records of that day. Nor was Joseph’s phenomenal rise to power unusual in the strange culture of that day and time. We must remember that Joseph was a Semite at a Semitic court. There is an unconscious introduction of a collateral fact in the simple statement of Genesis, chapter thirty-nine, verse one. After being told that Joseph was sold to a man named Potiphar, the statement is made that Potiphar was an Egyptian.

At first thought it would seem to be expected that a trusted officer in the court of a pharaoh would naturally be an Egyptian. The contrary is the case here, however. The pharaoh himself being an invader, he had surrounded himself with trusted men of his own race and family. As far as may now be ascertained, Potiphar was the only Egyptian who had preserved his life and kept his place at the court. He seems to have been the chief officer of the bodyguard of Pharaoh, and as such was entrusted with the dubious honor of executing the Pharaoh’s personal enemies. This, then, is a simple and passing statement that gives us an unexpected means of checking the scrupulous accuracy of the Genesis record.

Joseph was comely, attractive, and faithful. With an optimistic acceptance of his unfortunate circumstances, which seem much harder to us in our enlightened generation than would actually be the case to one accustomed to such vicissitudes of fortune, he set himself to serve with fidelity and industry. But above all this, the blessing of God rested upon him and upon all that he did. Since he was in the line of the promised Seed, and was under the direct blessing of that promise, it was inevitable that he should prosper.

There is a flood of illumination that shines upon this period from the frescoed tombs, the ancient papyri, and the records crudely inscribed upon walls and pillars. Particularly is this true of the entire section of Genesis that begins with the fortieth chapter and continues to the end of that Book.

Plate 5

{open burial}

{open burial}

{open burial}

Open burial lower left

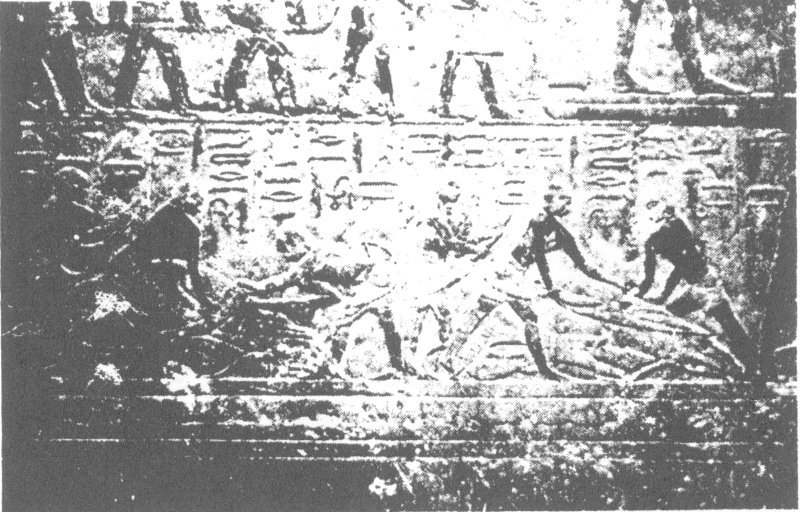

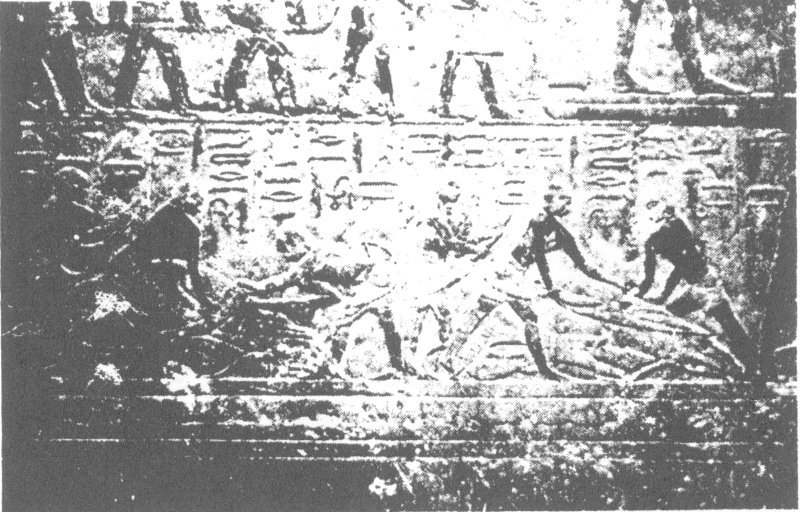

Another mural from an ancient tomb: butchers at work

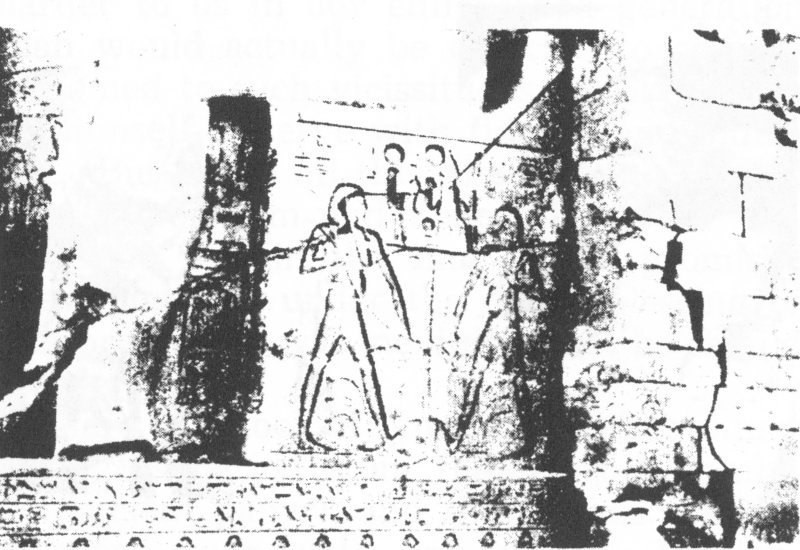

The god Hapi drawing the Two Kingdoms into one

Among the quaint frescoes of antiquity, there is one that has no word of explanation. There are many such murals in Egyptian tombs, and the cattle also figure often in the pictures on the papyri. (See Plate 9.) This fresco, however, was quite unique. Across the scene there parade fourteen cattle. The first seven are round, fat and in fine condition. They are followed by seven of the skinniest cows that ever ambled on four legs! No word of explanation is needed to clarify this scene for those who are familiar with the history of that time.

There is another mural showing the chief baker of Pharaoh, followed by his servants and porters. In his hand he holds a receipt for the one hundred thousand loaves that were daily delivered to the palace of Pharaoh. These “loaves” were in the nature of large buns.

The multiplicity of these paintings would require a volume to delineate carefully, but there is information here that cannot be passed over in silence. They bring to us the solution of one of those mysteries of Egyptian history, which is found in the collapse of the feudal system and the consequent complete possession of the land by the crown. We can now read from the secular evidences thus derived, that in a time of plenty a trusted lieutenant of the king built granaries to store the surplus left over from the time of plenty. Of course, to our enlightened times or in the culture of this generation, that is the height of ignorance. The proper thing to do in a time plenty is to destroy the surplus and plow under the excess. We sometimes wonder what would have happened in Egypt if our modern culture had prevailed in the seven years of plenty, in the light of the famine that followed!

We now find that when the whole land hungered, the lords ceded their real estate to the crown for grain to keep themselves and their families alive. The people sold themselves to Pharaoh and became slaves, on condition that he feed them as he would his cattle. When this time of famine was ended, Egypt was so absolute a monarchy that Pharaoh owned even the bodies of those who had been his subjects.

As an illuminating collateral incident, we now learn that a Sumerian name was given to Joseph, the trusted lieutenant. To him was accorded the title “Zaph-nath-pa-a-ne-ah.” The Sumerian meaning is “Master of hidden learning,” and was a title of honour and distinction which was conferred because of his wisdom and forethought in providing for the future. To him also was accorded the royal honour. He was to be preceded by a herald who called upon the people to bow down as Joseph passed by. Herein there comes the explanation of a slight philological difficulty in the text of Genesis. They have tried to make this title of honour to mean “Little Father.” This difficulty, however, disappears when we understand that it is not a Hebrew word that is found in the text, but an ancient Egyptian phrase. The common form of the word is “Ah-brak” and literally it means “bending the knee.” The Babylonian form of the word is “Abarakhu.” In some parts of the ancient world the term “Ah-brak” is still used by cameliers to make their beasts of burden kneel to receive their load. Thus when Joseph, the master of the hidden learning, went abroad throughout the land the herald preceded him crying, “Bend the knee,” and all the populace bowed in homage to him in acknowledgment of his distinguished accomplishments.

Against this background of understanding, we now turn our thoughts to one of the most stirring dramas in all human history. Again there was a famine in the entire land of Sumeria, and the people turned, as was customary, to the land of Egypt for succor and relief. Had this epic been invented by some literary genius of antiquity, the arrival of the brothers of Joseph to buy grain for their starving clan would be deemed one of the most melodramatic episodes ever conceived by the human mind. Therein we see again how God overruled the evil deed of the brethren, and by that very deed saved the guilty. In a time of world oppression and bitter famine, the family of Abraham was reunited in the shelter of Egypt.

As the story unfolds, we see the significance of Joseph’s instructions to his brethren. These Semitic kings were shepherds who highly prized their flocks and herds. The Egyptians, however, despised husbandry, and thus the monarchs were in great distress because of the want of capable herdsmen. The brethren of Joseph were distantly related to the reigning pharaoh. They were of the same race of people, and their father Abraham had been a prince in that land of Sumeria. So when the pharaoh asked them what their occupation was, recognizing them as distant relatives, they were canny enough to reply, “We be shepherds; to sojourn in the land are we come.” With great delight, the pharaoh employed them to be the personal overseers of his treasured animals.

Goshen, which consisted of two hundred square miles of fertility, and was the finest province and the juiciest plum in Egypt, was turned over to them for a pasture! They entered into a life of comparative ease, of absolute security, and of importance in the court of their day.

So there came into Egypt that group which was to constitute the spring that gave rise to the historic stream of the Hebrew people. The tribes were there in the persons of their founders, and the long contact of Israel and Egypt began through the pressure and want occasioned by a time of famine.

One further interesting and collateral evidence of the accuracy of these records is found in the various texts and sections of the Books of the Dead, and in the records of the customs and practices of the ancient art of embalming. In Egypt the general rule was to allow seventy days for the embalming of a dead body, the burial, and the mourning for the dead. But the fiftieth chapter of Genesis dealing with the death and burial of Joseph tells us, in the third verse, “And forty days were fulfilled for him; for so are fulfilled the days of those which are embalmed: and the Egyptians mourned for him threescore and ten days.”

These statements could be true only in the days of a Hyksos or Sumerian dynasty. The manner of embalming introduced by these Syrian conquerors, required forty days for the complete process and the burial. Seventy days was their custom for mourning, thus making a total of one hundred ten days. Only in these exact periods of Egyptian history could this record of Genesis be thus established and accredited.

It is a fascinating experience for the student of archeology to wend his way throug