Chapter 1: Background and History

If Muslims were always to be described as gullible, disorganised and inferior, what was it about attitudes towards their religion that caused Christian writers to hold such views? The answer may be that they were approaching the subject from a Christian perspective. They positively viewed their own religion as received, permanent and unbounded and, therefore, were not predisposed to see any other religion as having merit, worth or spiritual attraction, but were fanatically against. It was a matter of faith; faith that knew no transgression. The liberal West was light, the fundamentalist East darkness: centuries of tradition enforced this rule and it remains the foundation upon which discussion about Islam was shaped.

Writers perceived Islam as a source of danger, leading to what Roger Bacon termed pluralistically as ‘mysterious irrationalities’ in their relationships with Muslims and people of other faiths also including Hindus, Jainists, Zoroastrians, Buddhists and Jews. They were xenophobic in the sense that their country was best, their culture immutable and their religion sacrosanct. This hostility fostered myths in a manner so mysteriously rabid that any connection with the original was lost. Obviously, the outbreak of battles was the final link in this nationalistic, Christian preordination.

The Crusades, the battles against the Saracens, i. e. Muslims, were undertaken between 1095 and 1291 to recapture lands lost to Christendom, and specifically the Roman church. It was a movement to retake Jerusalem, defended by the great Saladin, or Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, for the West, and led to great bloodshed and a weakening of the Christian Byzantine Empire, which capitulated two centuries later to the Muslim Turks. In the late eleventh century, the resentment felt by Christians against the loss of the privileges in the ‘holy lands’ was so palpable that it led to a crusading zeal that swept across Europe, and involved King Richard I of England, better known as Richard the Lionheart, who sold off many of the country’s assets in his desire to raise money to embark on the Third Crusade in 1189.

Jerusalem had fallen to the First Crusaders in 1099. Many of its Christian, Muslim and Jewish populations were slaughtered. The Crusaders did not spare the lives of children, women or the elderly even after first assuring them of their safety. Saladin defeated King Guy's army in 1187 at the Horns of Hettin, and soon after recaptured Jerusalem. Unlike the Crusading armies, Saladin, who was a Muslim who followed the teachings of Islam, did not slay the city's Christian inhabitants, nor lay waste to the land. Saladin's virtuous acts gained him the respect of his enemies and of history.

King Richard I, who led the Third Crusade to recover Jerusalem, met Saladin in a conflict that was to be recorded in later chivalric romances. The Crusaders failed in their attempt, yet Saladin respected Richard I as an honourable opponent. Saladin's legendary generosity and sense of honour in conducting the treaty that ended the Crusade earned him the lasting respect not only of his contemporary rivals but also of the modern historian. As the historian, Norman Daniel has confirmed: ‘’It would probably be true to say that this legend was known over a wider area for a longer period of time than that of any political figure of the mediaeval West, and almost as favourably.’’[1]

Rather than becoming a hated figure in Europe, Saladin became a celebrated hero in literature, which can be observed in later literary accounts in the masculine romance form by Rider Haggard and others.

We will turn to look at the record of the early relationships between English literature and its attitudes to Muslims to investigate the phenomenon of disapproval – and unfortunately the pattern of fear and distrust begins. A thirteenth century English writer and philosopher, Roger Bacon, one of the earliest advocates of the modern scientific method, was inspired by the works of Aristotle and later Arabic works, such as the works of Muslim scientist Alhazen. Born in Ilchester in Somerset, England, possibly in 1213, Bacon was interested in the use of reason to promote Christianity. He held that only through intellectual argument could the faithful approach ‘infideles’ and thereby attempt to convert them. And even in the case of conversion, they would still have to become true believers and truly devout in order to qualify as Christians. The prophet Muhammad was considered by Bacon as the ‘Antichristus’, one who opposed Christ, and therefore, “it would be extremely useful to the Church of God to give thought to the time of [the law of Antichrist]: whether it will follow swiftly after the destruction of the law of Muhammad or much later…”[2]

The concept of the tribes of Gog and Magog that he introduced,[3] an undefined concept emanating from the Old Testament of the Bible in Genesis 10. 2, and also seen in the holy Qur’an, was imperative to him, for his followers should be made aware of their “condition and location”:

Since these peoples, confined in specific parts of the world, will emerge into a desolate region and meet Antichrist, Christians — especially the Roman Church — must consider well the position of these places. This will make it possible to comprehend the savagery of these tribes, and through that, the time of Antichrist’s arrival and place where he will appear.

Fear of the Antichrist, a Christian idea based on the New Testament, was well marked in his literature, for he advised Christians to resist and develop methods of defence against ‘the Antichrist’. He alarmed his followers by suggesting that he would use arts and powers known to scholars, despite the fact that Aristotle had used experimental science “when he delivered the world to Alexander… And Antichrist will use this wonderful science, far more powerfully than Aristotle.” Christians had always believed that powers that had been given to the Antichrist by the devil would help him, as the Venerable Bede[4] had suggested, to “perform magic greater than that of anyone else.” The irrational fear and superstition of these times was marked by Bacon in passages where the supposed evil, magic[5] and dark arts of the antichrist were a great challenge to the faithful, and particularly he suspected that, “Mongols and Muslims were already working against Christendom with such weapons: exercising fascination; stirring up mysterious irrationalities and dangerous impulses in the hearts of good Christians, sowing discord among the princes and causing wars among them.”

It is significant that the allegations of demonic power against Muhammad have been an early and continuous feature of anti-Muslim rhetoric, seen throughout the Middle Ages. These have generally continued until today, but not without a vigorous defence from Muslims everywhere. Since the Rushdie affair, Muslims have become far more proactive in defence of their religion. Some would wish to label this vigorous challenge as “terrorism”, yet such a facile appellation is not helpful in a democratic context where integration and multiculturism are desired norms, and where all the citizens of Britain can hold equal rights, representation and justice.

Supposedly born and bred in England, in the town of St Albans, but now disputed, Sir John Mandeville may have been the author of his ‘Travels’ which allegedly first appeared in translation from Anglo-Norman French, and circulated between 1357 and 1371. They were subsequently first printed by Wynkyn de Worde in 1499, when they were popularly enjoyed throughout Christendom. He translated the work of William of Tripoli who wrote an unsympathetic biography of Prophet Muhammad, rejecting much favourable information. Mandeville took a sympathetic view of Arabia, but not without the usual cavils about its desert nature:

Also the city of Mecca where Mohammet lieth is of the great deserts of Arabia; and there lieth [the] body of him full honourably in their temple, that the Saracens clepen [call ed.] Musketh. And it is from Babylon the less, where the soldan dwelleth, unto Mecca above-said, into a thirty-two journeys.

And wit well, that the realm of Arabia is a full great country, but therein is over-much desert. And no man may dwell there in that desert for default of water, for that land is all gravelly and full of sand. And it is dry and no thing fruitful, because that it hath no moisture; and therefore is there so much desert. And if it had rivers and wells, and the land also were as it is in other parts, it should be as full of people and as full inhabited with folk as in other places; for there is full great multitude of people, whereas the land is inhabited. Arabia dureth from the ends of the realm of Chaldea unto the last end of Africa, and marcheth to the land of Idumea toward the end of Botron. And in Chaldea the chief city is Bagdad.[6]

The ‘Father of English Literature’, the medieval poet and chronicler of the ‘Canterbury Tales’, Geoffrey Chaucer, born in 1343, wrote in middle English in a plain fashion about the events of the fourteenth century. He was a courtier, diplomat and civil servant who, as a renowned chronicler, became the first poet to be buried in the Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Recording the character of his Parson in ‘The Parson’s Tale’, he seems to belong to a Golden Age before the troublesome Islam came along. He portrays his Christian Parson as idealised and sentimentalised in contrast to his Wife of Bath who is bawdy, reckless and carnal. Such a juxtaposition may have been deliberate, for Chaucer sees more deeply into her character than he does the poor Parson, whose looking to worldly, materialistic qualities indicates that Chaucer has not enquired deeply into, nor is wholehearted about, the Christianity and the Church of his day. He draws back from the discovery of his own attitude to Christians and Christendom, even apologetically. This cripples his poetry.

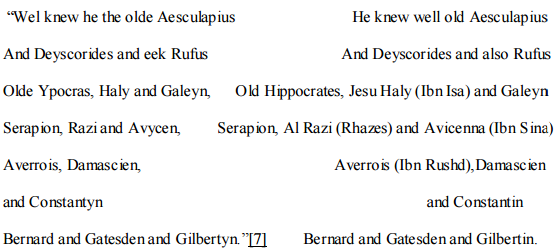

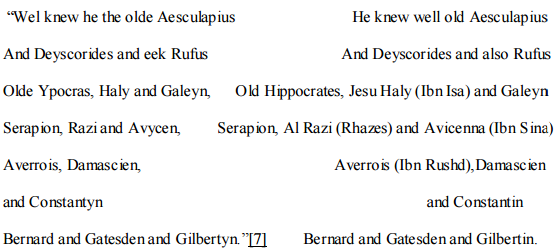

Chaucer had an awareness of Muslims and Muslimdom, for recording the knowledge of his ‘Doctour of Physic’ he demonstrates that Arab philosophy and medicine had characters that he could recognise as worthy of inclusion in the world of his pilgrims:

Chaucer cited these Arab scholars as the medical authorities for the Science of the time, in the ‘Prologue to the Canterbury Tales’. Ibn Isa, Al Razi, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Ibn Rushd were the four Arab physicians whose textbooks had been in use between the eighth and the twelfth century A.D. They were considered as the main sources of medical learning known to Europe from the early middle ages. These Arab physicians had been the basis of knowledge on medicine for four hundred years, and would continue to be so until the loss of Granada by the Muslims in 1492 to the kings of Castile.

These scholars included Adelard of Bath, who was a Western scholar who translated Al-Khwarizmi’s texts on astronomy and Euclid’s ‘Elements’ from Arabic into Latin. He was one of the first to introduce Indian numerals to Europe that now constitute our numbering system, 1,2,3 etc. He stands at the crossroads of three intellectual traditions: the classical learning of the French schools, the ancient Greek culture of Southern Italy, and the brilliant, original Arabic sciences. A popular theme was the Oriental tale written for Westerners. These included works by Petrus Alfonsi, an ex-Jewish writer converted to Christianity, who lived in Muslim Spain and author of the important text ‘Disciplina Clericalis’, which was the first collection of such works.[8]

Robert of Ketton, 1107 – 1160, was the first translator of the Qur’an into Latin in manuscript, known as the ‘Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete’; (another anti-Muslim slur) and also translated several scientific texts such as ‘Alchemy’ by Morienus Romanus. He entered the priesthood in a village in Rutland, a short distance from Stamford, Lincolnshire. Robert of Ketton is believed to have been taught at the Cathedral School of Paris. He travelled to the East from France for four years during 1134-1137 with his fellow student and friend, Herman Dalmatin, learning Arabic and writing about Islam.[9]

According to John Foxe, Chaucer’s work on religion was permitted by the bishops, referring to the Act of 1542, that authorised:

the works of Chaucer to remain still and to be occupied; who, no doubt, saw into religion as much almost as even we do now, and uttereth in his works no less, and seemeth to be a right Wicklevian, or else there never was any. And that, all his works almost, if they be thoroughly advised, will testify (albeit done in mirth, and covertly); and especially the latter end of his third book of the Testament of Love ... Wherein, except a man be altogether blind, he may espy him at the full: although in the same book …shadows covertly, as under a visor, he suborneth truth in such sort, as both privily she may profit the godly-minded, and yet not be espied of the crafty adversary.[10]

Foxe considered some of Chaucer’s works as being against his Puritanical view of religion, and doubted whether they represented the truth of Christian religion.

There was an interest in the Muslim East in the Elizabethan period. Richard Hakluyt copied the correspondence between the Ottoman queen mother, Queen Safiye and Elizabeth I in his ‘Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation’.[11] Hakluyt was educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford. He was the chaplain and secretary of Sir Edward Stafford, the English ambassador to the France between 1583 and 1588.

The potential for conflict with ‘Others’ such as Islamic people arises as early as the poet Edmund Spenser, who had sectarian, philosophical, linguistic and political difficulties with his contemporary life. Spenser includes the controversy of Elizabethan church reform within the epic, ‘The Fairie Queene’. His character, Gloriana, has religious English knights decimate Roman Catholic continental power in books 1 and 5. Spenser’s time saw conflict between the Protestant and Roman Catholic faiths, and it led to much sectarian division, just as exists today between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland, the precursor of so called ‘Islamist’ terrorism in the UK. Spenser believed that all religions were unclear in some way, and although we all search for a clear message, it is not possible to find it.[12]

There was a possibility of integration with Irish subjects, but the secular issues of social intercourse, marriage, politics and especially language were in great need of reform, and this extract suggests that his unhappiness with the state of affairs in Ireland prefigures the current situation, where a great social divide between the two communities exists, and persists even today in its insolubility:

Now this kynde of intercourse with the Irish breaded such acquayntaunce amitie and frendshipp between them and us, beinge so furnisht with theire Languadge that wee cared not contrary to our duties in balancing our creditte, to make fostered, gossiping, and marriadge as aforesaid with them so that now the English Pale and many other places of the kingdome that were planted with English at the first Conquests are growne to a confusion.[13]