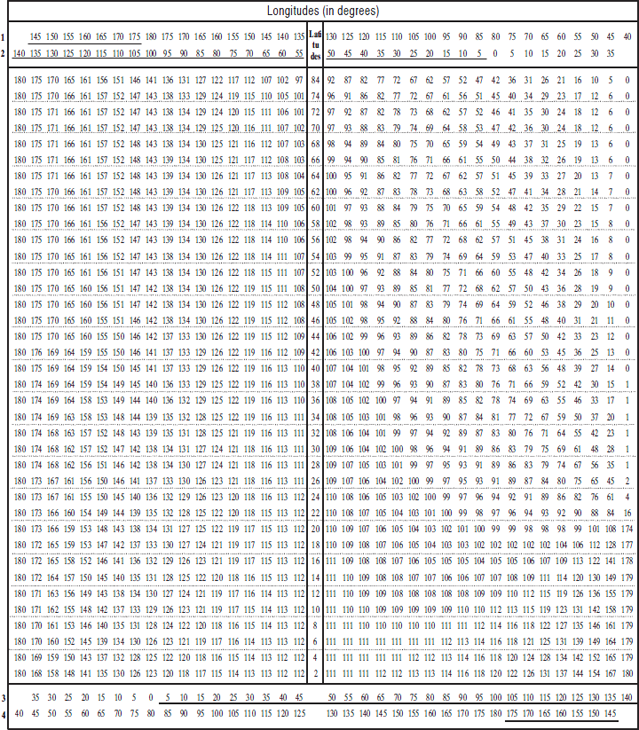

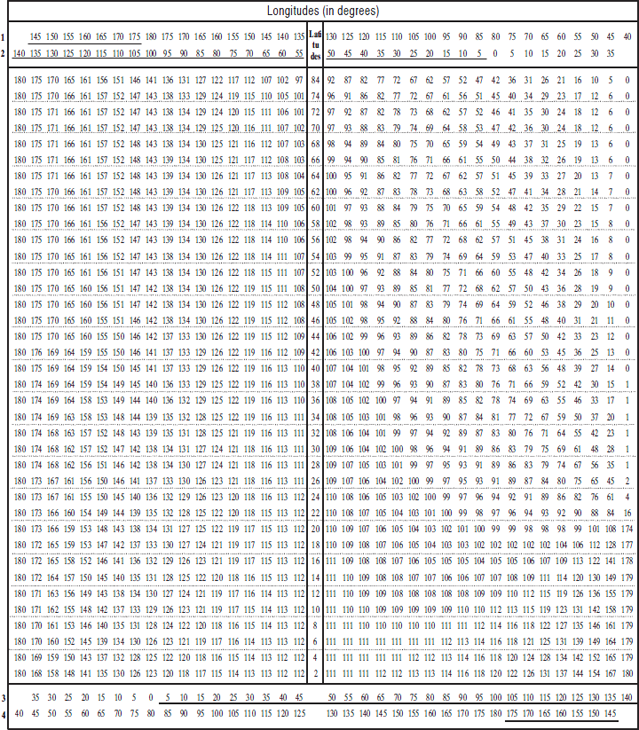

Qibla angles for places with

various latitudes and longitudes

Longitudes are printed in rows at the top and

bottom of the table in 5o intervals and Latitudes in the

middle column in 2o intervals. Longitudes that are

underlined are to the west (-) and the rest are to the east (+) of

London. Longitudes in the rows 1 and 2 are for the northern and 3

and 4 for the southern hemisphere. The figure on the intersection

of the column showing the longitude and the row showing the

latitude for a place gives the angle of Qibla Q for it. The Qibla

will be faced by turning Q degrees from the south to the west for

the rows 1 and 4 and to the east for the rows 2 and 3. These Q

angles are measured from the geographical south found by either the

Sun or the Pole-star. If the measurement is made with a magnetic

compass, the magnetic deviation (of the location) must be taken

into account.

10 – PRAYER TIMES

The hadith-i sherîf quoted in the books

Muqaddimet-us-salât, at-Tefsîr-al-Mazharî and al-Halabî

al-kabîr declares, “Jabrâîl ‘alaihis-salâm’ became my

imâm by the side of the door of Ka’ba for two days. We two

performed the morning prayer as the fajr (morning twilight)

dawned, the early afternoon prayer as the Sun departed from

meridian, the late afternoon prayer when the shadows of things

became as long as their heights, the evening prayer as the Sun

set [its upper edge disappeared]and the night prayer when

the evening twilight darkened. In the second day, we performed the

morning prayer when the morning twilight matured, the early

afternoon prayer as the lengths of the shadows of things (rods)

lengthened by twice as much as their heights, the late afternoon

prayer right after that, the evening prayer when the fast was

broken and the night prayer at the first one-third of the night.

Then he said ‘Oh Muhammad, these are the times of prayers for you

and theprophets before you. Let your Ummat perform each of

these five prayers between the two times at which we performed

each’.” This event took place on the fourteenth of July, one

day after the Mi’râj and two years before the Hegira. The Ka’ba was

12.24 metres tall, the solar declination was twenty-one degrees

plus thirty-six minutes, and its latitudinal location was

twenty-one degrees plus twenty-six minutes. Hence its earliest (and

shortest) afternoon shade (fay-e zawâl) was 3.56

cm.[65] Thus,

performing prayers (salât) five times a day became a commandment.

Hence, it is understood that the number of (daily) prayers is five

(per day).

It is fard (obligatory duty) for every Muslim

male or female who are ’âqil and bâligh, that is, who are sane and

pubert, that is, have reached the age for marriage, to perform

salât (prayer) five times a day in their correct times. If a salât

is performed before its due time, it will not be sahîh

(acceptable). In fact, it will be a grave sin. As it is fard to

perform a salât in its correct time for it to be acceptable, it is

also fard to know with no doubt that you have performed it in its

correct time. A hadîth in the book Terghîb-us-salâtdeclares,

“There is a beginning and an end of the time of each salât.”

The earth on which we live rotates around its axis in space. Its

axis is an imaginary straight line going through the earth’s center

and intersecting the earth’s surface at two symmetrical points.

These two points are termed the Poles. The sphere on whose inner

surface the sun and the stars are imagined to move is termed the

celestial sphere. Because the earth revolves around the sun,

we get the impression as if the sun were moving, although it is not

the case. When we look around, the earth and the sky appear to meet

on the curved line of a tremendous circle. This circle is termed

the apparent horizon. In the morning the sun rises on the

eastern side of this horizon. It moves up towards the middle of the

sky. Reaching its zenith at noontime, it begins to move down again.

Finally, it sets at a point on the western end of the apparent

horizon. The highest point it reaches from the horizon is the

time of noon (zawâl). At this time, the sun’s altitude from

the (apparent horizon) is termed the meridian altitude

(ghâya irtifâ’). A person who observes space is

calledobserver (râsıd). The earth’s radius intersecting the

earth’s surface at a point exactly under the observer’s feet is at

the same time the observer’s plumb line. The observer is at point

M, which is a certain distance above the earth’s surface. ME is the

observer’s plumb line. Planes perpendicalar to this plumb line are

termed the observer’s horizons.

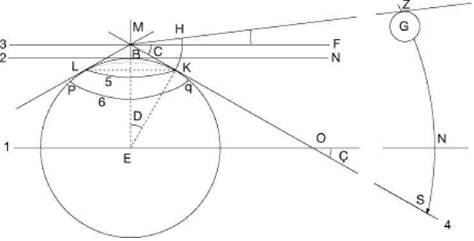

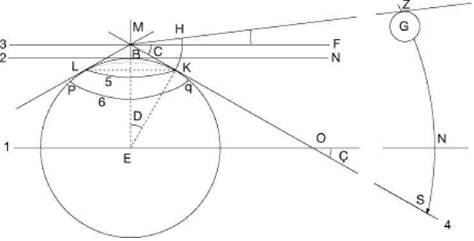

There are six horizons: Please read the

explanations below fig.1 A few pages ahead! 1– The plane MF,

termed (calculated horizon), which goes through the observer’s

feet. 2– The plane BN, termed (sensible horizon), which contacts

the earth’s surface. 3– The plane LK, termed (mer’î= valid, visible

horizon), which is represented with a circle, (circle LK), i.e. the

(apparent horizon) surrounding the observer. 4– The plane, termed

(true horizon), which goes through the earth’s centre. 5– The plane

P, termed (canonical horizon), which goes through the apparent line

of horizon belonging to the highest point of the place where the

observer is; the circle q where this plane intersects the earth’s

surface is termed (line of canonical horizon). These five planes

are parallel to one another. 6– The plane of sensible horizon

passing through the observer’s feet is termed the

surface(sathî) horizon. The higher the observer’s

location, the wider and the farther away from the sensible horizon

is the apparent horizon, and the closer is it to the true horizon.

For this reason, a city’s apparent prayer times may vary, depending

on the altitudes of its various parts. However, there is only one

prayer time for each prayer of namâz. Therefore, apparent horizons

cannot be used for prayer times. Shar’î (canonical) altitudes are

used because they are dependent on the shar’î (canonical) horizons,

which do not vary with height. Each prayer of namâz has three

different prayer times for three of the six different horizons of

every location: True; apparent (zâhirî); and shar’î (canonical)

times. Those who see the sun and the horizon perform (each prayer

of) namâz at its shar’î (canonical) time, which is when the sun’s

altitude from the shar’î horizon attains its position prescribed

for the prayer time. Those who do not see them perform their

prayers of namâz at their shar’î times determined by calculation.

However, altitudes based on shar’î (canonical) horizons are longer

than apparent altitudes based on apparent horizons. These horizons

cannot be used because prayer times are after noon. There are

calculated and mer’î (observed, valid) times for each of the

aforesaid times of namâz. Calculated (riyâdî) times are determined

by calculation based on the sun’s altitude. Mer’î times are

obtained by adding eight (8) minutes and twenty (20) seconds to

calculated times. For, it takes the sun’s rays eight minutes and

twenty seconds to come to the earth. Or it is determined by

observing that the sun has reached a certain altitude. Namâz is not

performed at calculated or true times. These times are used as a

means for determining the mer’î times. The sun’s altitude is zero

at sunrise and sunset. The altitudinal changes above the apparent

horizon begin at sunrise before noon, and they begin after true

horizon after noon. Shar’î (canonical) horizon is before true

horizon before noon, and it follows true horizon after noon. The

sun’s altitude at the time of fajr-i-sâdiq (true dawn) is

–19o according to all four

Madhhabs.[66] Its altitude to

initiate the time of night prayer is –19o according to

Imâm-i-a’zam (Abû Hanîfa, the leader of Hanafî Madhhab), and

–17o according to the two Imâms (Imâm Muhammad and Imâm

Abû Yûsuf, two of Imâm-i-a’zam’s disciples), and according to the

other three Madhhabs. The altitude to indicate the beginning of

early afternoon prayer is the meridian altitude (ghâya irtifâ’),

which, in its turn, is the algebraic multiplication of the

complement of latitudinal degrees and (the sun’s) declination.

Mer’î-haqîqî noon time (zawâl) is when the center of the sun

is observed to have reached the maximum (meridian altitude) with

respect to the true horizon. The altitudes for the early and late

afternoon (’asr) prayers change daily. These two altitudes are

determined daily. Since it is not always possible to determine (by

observation) the time when the edge of the Sun reaches the altitude

from the apparent horizon for a certain prayer, the books of fiqh

explain the signs and indications of this mer’î (valid) time (for

each prayer). This means to say that the apparent times of namâz

are the mer’î times, not the calculated times. Those who are able

to see these indications in the sky may perform their daily prayers

at these apparent times. Those who are not able to see these

indications as well as those who prepare calendars, calculate the

riyâdî times when the edge of the Sun arrives at the relevant

altitudes with respect to the surface horizon in the afternoon.

When the time clocks show these calculated times, they perform

their prayers within these mer’î times.

By calculation, the riyâdî times when the sun

reaches the prescribed altitudes from the true horizon are

determined. That the sun has reached this mer’î time (or altitude)

is observed eight minutes and twenty seconds after this calculated

time; this time (of observation) is called mer’î time. In

other words, the mer’î time is eight (8) minutes and twenty (20)

seconds after the riyâdî time. Since the beginning times whereto

the time clocks are adjusted, i.e. the times of true noon and

adhânî sunset, are mer’î times, the riyâdî times indicated by the

time clocks are mer’î times. Although the riyâdî (calculated) times

are written in calendars, they change into mer’î times on the time

clocks. For instance, if a certain time found by calculation is,

say, three hours and fifteen minutes, this riyâdî three hours and

fifteen minutes becomes a mer’î time of three hours and fifteen

minutes on the time clocks. First the haqîqî riyâdî times,

when the center of the sun reaches the altitudes prescribed for the

prayers of namâz from the true horizon, are found by calculation.

Then these times are converted into shar’î riyâdî times by

means of a process performed with the time called tamkîn. In

other words, there is no need for also adding 8 minutes and 20

seconds to the riyâdî times on the time clocks. The difference of

time between true time and the shar’î time for a certain prayer of

namâz is termed the time of tamkîn. The time of tamkîn for each

prayer time is approximately the same.

In a location, the time for the morning

prayer begins, in all the four Madhhabs, at the end of

canonical night, that is, with the sighting of the whiteness

called fajr sâdiq(true dawn) at one of the points on the

line of ufq-i zâhirî (apparent horizon) in the east. This time is

also the beginning of fast. The chief astronomer Ârif Bey reports,

“Since there are weak reports saying that the fajr sâdiq (true

dawn) begins when the whiteness spreads over the horizon and the

altitude of the Sun is -18o or even -16o, it

is judicious and safe to perform the morning prayer 20 minutes

later than the time shown on calendars.” The altitude (of the Sun)

for the fajr (morning twilight) is determined by observation of the

line of apparent horizon in a clear night sky by using our watch.

Since times corresponding to various altitudes are determined by

calculation, the altitude used in the calculation of the time

complying with the observed time, is the altitude for the fajr

(dawn). The altitude of the shafaq (the disappearance of the

evening twilight) is determined with the same procedure. For

centuries, Islamic scholars have adopted the altitude for fajr as

-19o, and have reported that values other than this are

not correct. According to Europeans, dawn (fajr) is the spreading

of the whiteness,[67] and the

sun’s altitude is –18o at dawn. Muslims’ religious

tutors are the Islamic scholars, and not the Christians or those

people who have not adapted themselves to any of the (four)

Madhhabs. The time of morning prayer ends at the end of zahirî

night (solar or apparent night), that is, when the

front [upper] edge of the Sun is seen to rise from the apparent

horizon.

The celestial sphere, with the earth at

its centre like a point, is a large sphere on which all the stars

are projected. The prayer times are calculated by using the arcs

of altitude, which are imagined to be on the surface of this

sphere. The two points at which the axis of the earth intersects

the celestial sphere are called the celestial poles. The

planes passing through the two poles are called the planes of

declination. The circles that these planes form on the celestial

sphere are called circles of declination. The planes containing the

plumb-line of a location are called the azimuth planes (or

vertical planes). The circles formed by the imagined intersection

of planes containing the plumb-line of a location and the celestial

sphere are called the azimuth or altitude circles (or

verticals). The azimuth circles of a given location are

perpendicular to the horizons of that location. At a given

location, there is one plane of declination and an infinite number

of azimuth circles. The plumb-line of a location and the axis of

the earth (may be assumed to) intersect at the centre of the earth.

The plane containing these two lines is both an azimuthal and a

declination plane of the location. This plane is called the

meridian plane of the location. The circle of intersection

of this plane with the celestial sphere is called the meridian

circle A location’s meridian plane is perpendicular to its

plane of true horizon and divides it by half. The line whereby it

cuts through its plane of true horizon is termed the meridian line

of the location. The arc between the point of intersection of the

azimuth circle (vertical) passing through the Sun and true horizon

and the Sun’s centre is the arc of true altitude of the Sun

at a given location at a given time. The Sun crosses a different

azimuth circle every moment. The angles measured on an azimuth

circle between the point at which the circle is tangent to the

Sun’s edge and the point at which it intersects the sensible,

apparent, mathematical and superficial horizons are called the

Sun’s apparent altitudes with respect to these horizons. Its

superficial altitude is greater than its true altitude. The times

when the Sun is an equal altitude from each of these horizons are

different. The true altitude is the angle between the two straight

lines projecting from the earth’s centre to the two ends of the arc

of true altitude in the sky. The angular measures of infinite

number of circular arcs of various lengths between these two half

straight lines and parallel to this arc are all the same and are

all equal to the angle of true altitude. The two straight lines

that describe the other altitudes originate from the point where

the plumb line of the place of observation intersects the horizon.

The plane passing through the centre of the earth perpendicular to

its axis is called the equator plane. The circle of

intersection of the equatorial plane with the Globe is called the

equator. The place and the direction of the equatorial plane

and those of the equator never change; they divide the earth into

two equal hemispheres. The angle measured on the circle of

declination between the Sun’s centre and the equator is called the

Sun’s declination. The whiteness before the apparent sunrise

on the line of apparent horizon begins two degrees of altitude

prior to the redness, that is, it begins when the Sun ascends to an

altitude of 19o below the apparent horizon. This is the

fatwâ[68]. Non-mujtahids

do not have the right to change this fatwâ. It has been reported in

Ibn ’Âbidîn (Radd-ul-muhtâr) and in the calendar by M.Ârif

bey that some ’ulamâ said that it began when the Sun is a distance

of 20o (from the apparent horizon). However, acts of

worship that are not performed in accordance with the fatwâ are not

sahîh (acceptable).

The daily paths of the Sun are circles on the

(imaginary inner surface of the) celestial sphere and that are

(approximately) parallel to one another and to the equatorial

plane. The planes of these circles are (approximately)

perpendicular to the earth’s axis and to the meridian plane, and

intersect the horizontal plane of a given location at an angle

(which, in general is not a right angle); that is, the daily path

of the Sun does not (in general) intersect the line of apparent

horizon at right angles. The azimuth circle through the Sun

intersects the line of apparent horizon at right angle. When the

Sun’s centre is on the meridian circle of a location, the circle of

declination going through its center and the location’s azimuthal

circle coexist, and its altitude is at its daily maximum (from the

true horizon).

The time of apparent zuhr, that

is, the time of apparent early afternoon prayer is to be

used by those who can see the Sun. This mer’î time begins as the

Sun’s rear edge departs from the apparent zawâl or noon. The Sun

rises from the superficial horizon, that is, from the apparent

horizon, which we, of a given location. First, the time of

apparent-mer’î zawâl begins when the front edge of the Sun at

its maximum altitude (from the superficial horizon), that is, from

the apparent horizon, which we observe reaches the circle of

the apparent zawâl position peculiar to this altitude in the sky.

This moment is determined when you no longer perceive any decline

in the length of the shadow of a pillar (erected vertically on a

horizontal plane). Following this, the time of true-mer’î

zawâl is when the centre of the Sun is at the meridian [midday]

of the location, that is, when it is at its daily maximum altitude

from the true horizon. Thereafter, when its rear edge descends to

its maximum on the western side of the superficial horizon of the

location, the time of apparent-mer’î zawâl ends, the shadow

begins to lengthen, and it is the beginning of the time of

apparent-mer’î zuhr. The motion of the Sun and the tip of

the shadow are imperceptibly slow as it ascends from the apparent

noon time to true noon time, and as it descends thence to the end

of the apparent noon time, because the distance and the time

involved are quite short. When the rear edge descends to its

maximum height on the western side of the superficial horizon of

the location, the time of apparent mer’î zawâl ends and the

time of canonical mer’î zuhr begins. This time is later than

the time of true zawâl by a period of Tamkîn. For the

difference of time between the true and the canonical zawâls is

equal to the difference of time between the true and the canonical

horizons, which in turn is equal to the time of Tamkîn. The

zâhirî (apparent) times are determined with the shadow of the

pillar. The canonical times (of the prayers) are not found with the

shadow of the pillar. The true time of noon is found by

calculation, time of Tamkîn is added to this, hence the

riyâdî (calculated) shar’î (canonical) time of zawâl (noon). The

result is recorded in calendars. The canonical time of zuhr

continues until the ’asr awwal, that is, the time when the

shadow of a vertical pillar on a level place becomes longer than

its shadow at the time of true zawâl by as much as its height, or

until ’asr thânî, that is, until its shadow’s length

increases by twice its height. The former is according to the Two

Imâms [Abû Yûsuf and Muhammad ash-Shaybânî], and the latter is

according to al-Imâm al-a’zam.

Although the time of late afternoon

prayer begins at the end of the time of early afternoon prayer

and continues until the rear edge of the Sun is seen to set at the

line of apparent horizon of the observer’s location, it is harâm to

postpone the prayer until the Sun goes yellow, that is, until the

distance between the Sun’s lower [front] edge and the line of

apparent horizon is a spear’s length, which is five degrees (of

angle). This is the third one of the daily three times of kerâhat

(explained towards the end of this chapter). Calendars in Turkey

contain time-tables wherein times of late afternoon prayers are

written in accordance with 'asr awwal. For (performing late

afternoon prayers within times taught by Imâm a'zam and thereby)

following Imâm a'zam, late afternoon prayers should be performed 36

minutes, (in winter,) and 72 minutes, (in summer,) after the times

shown on the aforementioned calendars. In regions between latitudes

40 and 42 a gradanational monthly addition of the numerical

constant of 6 to 36 from January through June and its subtraction

likewise from 72 thenceforward through January, will yield monthly

differences between the two temporal designations termed 'asr,

(i.e. 'asr awwal and 'asr thânî).

The time of evening prayer begins when

the Sun apparently sets, that is, when its upper edge is seen to

disappear at the line of apparent horizon of the observer’s

location. The canonical and the solar nights also begin at this

time. At locations where apparent sunrise and sunset cannot be

seen, and in calculations as well, the shar’î times are used. When

the sunlight reaches on the highest hill in the morning; it is the

shar’î (canonical) time for sunrise. And in the evening; when it is

seen to disappear down the highest hill on the western horizon, it

is the mer’î shar’î time for sunset. The adhânî time clocks are

adjusted to twelve (12) o’clock at this moment. The time of evening

prayer continues until the time of night prayer. It is sunna to

perform the evening prayer within its early time. It is harâm to

perform it in the time of ishtibâk-e nujûm, that is, when

the number of visible stars increase, that is, after the rear edge

of the Sun has sunk down to an altitude of 10o below the

line of apparent horizon. For reasons such as illness,

travelling,[69] or in order to

eat food that is ready, it might be postponed until that

time.

The time of night prayer begins,

according to the Two Imâms,[70]

with ’ishâi-awwal, that is, when the redness on the line of

apparent horizon in the west disappears. The same rule applies in

the other three Madhhabs. According to Imâm-al-a’zam it begins with

’ishâi-thânî, that is, after the whiteness disappears. It

ends at the end of canonical night, that is, with the whiteness of

fajri-sâdiq (true dawn) according to Hanafî Madhhab. The

disappearing of redness takes place when the upper edge of the Sun

descends to an altitude of 17o below the superficial

horizon. After that, the whiteness disappears when it descends to

an altitude of 19o. According to some scholars in the

Shâfi’î Madhhab, the latest (âkhir) time for night prayer is until

canonical midnight. According to them, it is not permissible to

postpone the performance of night prayer beyond canonical midnight.

And it is makrûh in the Hanafî Madhhab. In the Mâlikî Madhhab,

although it is sahîh (acceptable) to perform it until the end of

canonical night, it is sinful to postpone and perform it after the

initial one-third of the night. He who could not perform the early

afternoon and the evening prayers of a certain day in the times

prescribed by the Two Imâms must not postpone them to qadâ but must

perform them according to al-Imâm-al-a’zam’s prescription; in that

case, he must not perform the late afternoon and the night prayers

of that day before the times prescribed for these prayers by

al-Imâm-al-a’zam. A prayer is accepted as to have been performed in

time if the initial takbîr is said before the end of the prescribed

time in Hanafî, and if one rak’a is completed in Mâlikî and

Shâfi’î. In his book A. Ziyâ Bey notes in his book’Ilm-i

hey’et:.

“As one approaches the poles, the

beginnings of the times for morning and night prayers, i.e. the

times morning and evening twilight, become farther apart from the

times of sunrise and sunset, respectively. Prayer times of a

location vary depending on its distance from the equator, i.e., its

degree of latitude, ö, as well as on the declination, S, of the Sun, i.e., on months and days.” [At

locations where latitude is greater than the complement of

declination, days and nights do not take place. During the times

when the sum of latitude and declination is

90o-19o = 71o or greater, that is,

90o-ö ≤ S +19o or ö+ S

≥ 71o, for example, during the

summer months when the Sun’s declination is greater than

5o, fajr (dawn, morning twilight) begins before the

shafaq (evening dusk, evening twilight) disappears. So, for

instance, in Paris where the latitude is 48o50', the

times of night and morning prayers do not start during 12 to 30

June. In the Hanafî Madhhab, the time is the reason (sabab) for

performing prayer. If the reason is not present, the prayer does

not become fard. Therefore, these two prayers (salâts) do not

become fard at such places. However, according to some scholars, it

is fard to perform these two salâts at their times in nearby

countries or places. [During the periods of time (12 to 30 June)

when the times of these two prayers of namâz do not virtually

begin, it is better to (try and find the times that these two

prayers were performed on the last day of the period during which

their prescribed times virtually began and to) perform them at the

same times].

The time of Duhâ (forenoon) begins when

one-fourth of nehâr-i-shar’î, i.e., the first quarter of the

canonically prescribed duration of day-time for fasting, is

completed.

Half of the nehâr-i-shar’î is called the time

of Dahwa-i-kubrâ. In adhânî time (reckoned from sunset)

dahwa-i-kubrâ=Fajr+(24-Fajr)÷2=Fajr+12-Fajr÷2=12+Fajr÷2. Hence,

half the time of Fajr gives the time of Dahwa-i-kubrâ reckoned from

12 in the morning. (For example), in Istanbul on the 13th of

August, the time of dawn in standard time is 3 hours 9 minutes, the

standard time of sunset is 19 hours 13 minutes, and therefore, the

daytime is 16 hours 4 minutes and the standard time of

Dahwa-i-kubrâ is 8:02+3:09=11 hours 11 minutes.

In other

K = The point at which the azimuthal plane

through the Sun intersects the line of apparent horizon.

MS = The plane of superficial horizon tangent

to the Globe at point K, perpendicular to the plumb-line at

K.

HK = The altitude of point K on the line of

apparent horizon with reference to the direction of the Sun, MZ.

This is the altitude of the Sun with respect to the line of

apparent horizon. This altitude is equal to the altitude ZS of the

Sun with respect to the superficial horizon.

ZS = The arc of azimuthal circle giving the

altitude of the Sun with reference to the superficial horizon. This

angle is equal to the angle subtended by the arc HK.

D=C=Ç=Angle of dip of horizon.

M = A high place of the location.

O = A point on the straight line of

intersection of true and superficial horizons.

1 = The plane of true horizon 2.

G = The Sun as seen from the Earth.

GA = The true altitude of the Sun.

B = The lowest place of the location words, it

is equ