CHAPTER VI

When I come to look back upon that Saxon period, spent in the green shades of my sweet franklin’s homestead, it seems, perhaps, that never was there a time so peaceful before in the experience of this passion-tossed existence! We hunted and we hawked, we feasted and we lay abask in the sunshine of a jolly, idle life all these luxurious months, drinking scorn and confusion amid our nightly flagons to remote care and (as it seemed) remoter Normans.

But first to tell you how I won the right to lord it over these merry Saxon churls and dissolute thanes. Editha had hardly come to her home and dried, in a day or two, her weeping eyes, when all the noble vagrants from yonder battle were up in arms to woo her. Never was maid so sued! From morning till night there was no rest or peace. From the uppermost bower looking over the fair English glades, down into the thickets of nut and hazel, the air reeked of love and petitions. The mighty Dane, like a sick bear, slept upon her curtained threshold and growled amorousness into her timid ear before the sun was up. The Welsh Prince wooed her all her breakfast-time, and his tawny harper spent many a golden morning in outlining his noble patron’s genealogy. In faith—ap Tudor, ap Griffith, ap Morgan, ap Huge, and I know not how many others, it seemed all had a hand in the making of that paragon—but Editha blushed and said she feared one Saxon girl was all too few for so many. They besought her up and down, night and morning, full and empty, to wed them. The English Princelings dogged her footsteps when she went afield, and Torquil and Wulfhere, those bandaged lovers, were ready for her with sighs and plaintive proposals when she came flitting, frightened and fearful, home through the bracken.

How could this end but in one way for the defenseless girl? She was sued so much and sued so hot that one day she came creeping like a hunted animal to the turret nook where I sat brooding over my fortunes, and, timorous and shy, begged me to help her. I stood up and touched her yellow disheveled hair, and told her there was but one way—and Editha knew it as well as any one—and had made her choice and slipped into my arms and was happy.

That was as noisy a wedding as ever had been in Voewood. Editha freed a hundred serfs, and all day long the noise of files on their iron collars echoed through her halls. She fed at the door every miscreant or beggar who could crawl or hobble there, and remitted her taxes to a score of poorer villains.

In the hall such noisy revelers as the rejected suitors surely never were seen. They began that wedding feast in the morning, and it was not finished by night. To me, who had so lately supped amid the costly detail, the magnificent and cultivated license of a patrician Roman table, these Saxon rioters seemed scrambling, hungry dogs. Where Electra would taunt her haughty courtiers over loaded tables which the art of three empires had furnished, firing her cruel, witty arrows of spite and arrogance from her rose-strewn couches, these rough, uncivil woodland Peers but wallowed in their ceaseless flow of muddy ale, gorged themselves to sleep with the gross flesh of their acorn-fed swine, and sang such songs and told such tales as made even me, indifferent, to scowl upon them and wonder that their kinswoman and her handmaids could sit and seem unwotting of their gross, obscene, and noisy revels.

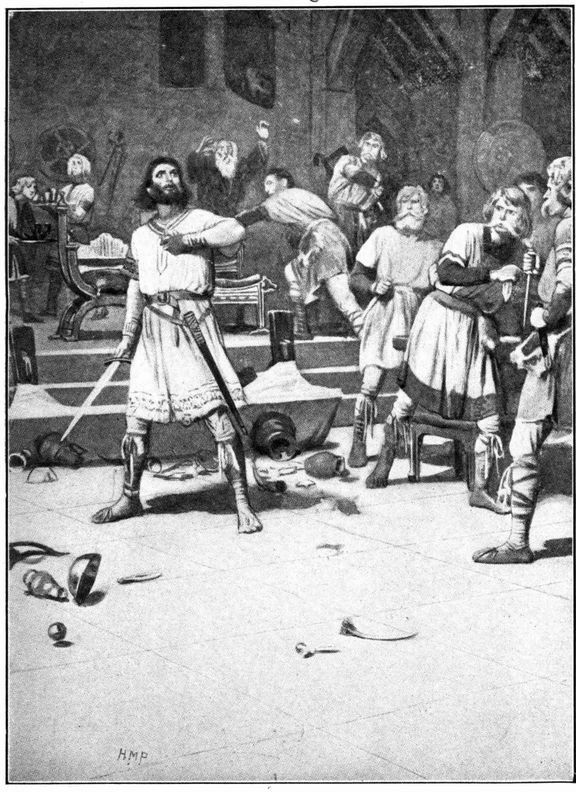

And late that night blood was nearly spilled upon the oaken floor of Voewood. The thanes had fairly pocketed their disappointment, but now, deep in drink and stuffed with food and courage, they began to eye me and my thin-hid scorn askance, and then presently, like the mutter of a quick-coming storm, came the whisper, “Why should she fall to the stranger? Why? Why?” It flew round the tables like wildfire, and half-emptied beakers were set down, and untasted food stopped on its way to the mouth, and then—all on a sudden, the drunken chiefs were on foot advancing to the upper table, where I sat by Editha’s right hand, their daggers agleam in the torchlight shining upon their red and angry faces as they came tumbling and shouting toward us, “Death to the black-haired stranger! Voewood for a Saxon! Why should he win her?”

’Tis not my fashion to let the foeman come far to seek me, and I was up in an instant—overturning the table with all its wines and meats—and, whipping out my sword, I leaped into the middle of the rushy space before them.

“Why?” I shouted. “Why? you drunken, Norman-beaten dogs! Why? Because, by Thor and Odin! by all the bones of Hengist and his brother! I can throw a straighter javelin, and whirl a heavier sword, and sit a fiercer steed than any of you. Why? Because my heart is stronger than any that ever beat under your dirty scullion doublets. Why? Because I scorn, and spit upon, and deride you!”

It was braggart boasting, but I noticed the Saxons liked their talk of that complexion. And in this case it was successful. The Princes stood hesitating and staring as I towered before them, fiery and disdainful, in the red gleaming banquet lights; until presently the youngest there burst into a merry laugh to see them all thus at bay, chewing the hilts of their angry daggers, and each one waiting for his neighbor to prove himself the braver, by dying first upon my weapon. That laugh had hardly reached the ruddy oaken rafters overhead when it was joined by a score of others, and in a moment those wilful Saxon lordlings were all laughing and jerking back their steels, and scrambling into their supper-places as if they had not broken their fast since morning, and I were their mother’s son.

The Princes stood hesitating as I towered before them

Deep were their flagons that night, after the women had stolen away, and Idwal ap Howell filled the hall with wild Welsh harping that stirred my soul like a battle-call; for it was in my dear British tongue, and full of the color, light, and the life that had illuminated the first page of my long pilgrimage. And the Saxon gleemen, not to be outdone, each sang the song that pleased him best; and the Welshman strove to drown them with his harping; and the thanes sang, all at once, whatever songs were noisiest and most licentious. Mighty was the fire that roared up the open hearthplace; deep was the breathing of vanquished warriors from under the tables; red was the spilled wine upon the floor—when presently they put me upon a tressel, and, bearing me round the hall in discordant triumph, finally bore me away to the inner corridors, and left me at a portal where I never yet had entered!

There is but little to say of that quiet Saxon rest that befell me in pleasant Voewood. Between each line I pen you must suppose an episode of pleasure. In the springtime, when the woods were shot with a carpet of blue and yellow flowers, we lay a-basking in the sunny angles or rode out to count our swine and fallow deer. In the summer, when all Editha’s mighty woodlands were like fair endless colonnades, we basked amid the flickering shadows and watched the sunny sheen upon the treetops, to the orchestra of little birds. And autumn, that touched the vassals’ corn-clearings with yellow, saw my proud Norman charger grow fat and gross with new grain. September rains and mists rusted my silent weapon into its sheath; even winter, that heard the woodman’s axe upon the forest trees, and saw bird and beast and men and kine draw in to the gentle bounty of my white-handed lady, was but a long, inglorious holiday of another sort.

Many and many a time, in those merry months, did this Phœnician laugh to his mirror to see how fitly he could wear upon his Eastern-British-Roman body the Danish-Saxon-English tunic! It was all of fine linen the franklin’s own fair fingers had spun, and pointed and tasseled and parti-color, and his legs were cross-gartered to his knees, and his little luncheon-dagger hung by his jeweled belt, and a fillet of pure English gold bound down the long black locks that fell upon his shoulders. Every morning Editha combed them out with her silver comb, and double-peaked his beard, kissing and saying it was the best in all Voewood. He had more servants than necessities in those times, and almost his only grievance was a lack of wants.

The Normans for long had left us wholly alone, partly through the usurper cunning which prompted our new tyrant to deal gently with those who had stood in arms against him, but principally in our case since the strong tide of invasion had swept northward beyond us, and Voewood slept unharmed, unnoticed among its green solitudes—a Saxon homestead as it had been since Hengist’s white horse first flaunted upon an English breeze and the seven kingdoms sprang from the ashes of old Roman Britain.

So we lived light-hearted from day to day, forgetting all about the battle by Senlac, and drinking, as I have said, in our evening wassails confusion and scorn of the invaders who seemed so distant. It was a good time, and I have little to note of it. Many were the big boars which died upon my eager spear down in the morasses to the southward, and I came to love my casts of tiercelets and my hounds as though I had been born to a woodman’s cape and had watched the fens for hernshaws and followed the slot of wounded deers from my youth upward.

All these things led me into many a wild adventure and many a desperate strait; but one of them stands out from the rest upon the crowded pages of my memory. I had, one day when Editha was with me, mounted as she would be upon her palfrey, slipped the dogs upon a stag an arrow of mine had wounded in the foreleg, and, excited by the chase and reluctant as ever to turn back from an unaccomplished purpose, we followed far into the unknown distances, and all beyond our reckonings. I had let fly that shaft at midday, and at sundown the stag was still afoot, the dogs close behind him, and I, indomitable, muddy, and torn from head to foot, but with all the hunter instinct hot within me, was pressing on by my Saxon’s bridle rein. Endless, rough, and tangled miles had we run and scrambled in that lengthy chase, and neither of us had noticed the way, or how angry the sun was setting in the west.

Thus it came about that when the noble hart at length stood at bay in the lichened coverts under a bushy crag, there was hardly breath in me to cheer the weary dogs upon him, and hardly light enough to aim the swift thrust of my subduing javelin which laid him dead and bleeding at our feet. Yes, and before I could cut a hunter’s supper from that glossy haunch the dome of the sky closed down from east to west, and the first heavy drops of the evening rain came pattering upon the leaves overhead. Thor! how black it grew as the wind began to whistle through the branches and the murky clouds to fly across the face of the somber heaven, while neither east nor west could any limit be seen to the interminable vastnesses of the endless woodlands! In vain was it we struggled for a time back upon our footsteps, and then even those were lost; and, as the sky in the east burned an angry yellow for a moment before the remorseless night set in, it gave us just light to see we were hopelessly mazed in the labyrinths of the huge and lonely forest.

It was thus we turned to take such shelter as might offer, and that gleam shone for a moment pallid, yellow, and ghastly upon a cluster of gray stones standing on a grassy mound a quarter of a mile away. Thither we struggled through the black mazes of the storm, the headlong rain whistling through the misty thickets like flights of innumerable arrows, the angry wind lashing the treetops into bitter complaining, and waving abroad (in the sodden dismal twilight) all the long beards of goblin lichens hanging in ghostly tapestry across our path that dreary October evening.

Reeling and plunging to the shelter through a black world of tangled witnesses, with that mocking gleam behind shining like a window of the nether world, and overhead a gaunt, hurrying array of cloudy forms, we were presently upon the coppice outskirt, and there I stopped as though I had grown to the ground.

I stopped before that great, gaunt amphitheater of gray stones and stared and stared before me as though I were bereft of sense. I rubbed my eyes and pointed with trembling, silent finger, and looked again and again, while the Saxon girl crouched to my side, and my hounds whined and shivered at my feet, for there, incredible! monstrous!—yellow and shining in the pallid derision of the twilight, stern, hoary, ruinous, mocking—overthrown and piled one upon another, clasped and knotted about their feet by the knotted fingers of the woodland growth, swathed in the rocking mists which gave a horrid life to their cruel, infernal deadness, were the stones, the very stones of that Druid altar-place upon which I was sacrificed nearly a thousand years before!

Here was a pretty welcome! Here was a cheerful harborage! What man ever born of a woman who would not have been dazed and dumfounded at this sudden confronting—this extraordinary reminiscence of the long-forgotten? It overwhelmed for the moment even me—me, Phra the Phœnician, to whom the red harvest-fields of war are pleasant places, who have dallied with the infinite, and have been a melancholy coadjutor of Time itself. Even me, who never sought to live, yet live endlessly by my very negligence—who have received from the gods that gift of existence that others ask for unanswered.

I might have stood there as stolid and grim as any one of those ancient monoliths all through the storm but for the dear one by my side. Her nestling presence roused me, and, gulping down the last of my astonishment, and seeing no respite in the yellow eye of the night over my shoulder, I took the hand that lay in mine with such gentle trust and, with a strange feeling of awe, led her into the magic circle of the old religion.

The very altar of my despatch was still there in the center, but time and forest creatures had worn out from under that mighty slab a little chamber, roofed with that vast flagstone and sided by its three supports—a space perhaps no bigger than the cabin of my first trading felucca, yet into this we crept, with the reluctant hounds behind us, while the tempest thundered round, and, loth to lose us, sought here and there, piping in strange keys among those time-worn relics of cruelty, and singing uncouth choruses down every crevice of our wild retreat.

Pleasure and Pain are sisters, and the little needs of life must be fulfilled in every hour. I comforted my comrade, piling for her a rough couch of the broken litter upon the floor, stuffing up the crannies as well as might be with damp sods, and then making her a fire. This latter I effected with some charcoal and burned ends of wood that lay upon an old shepherd’s hearth in the center of the chamber, and we kept it going with a little store of wood which the same absent wanderer had gathered in one corner but had failed to use. More; not only did we mend our circumstances by a ruddy blaze that danced fantastically upon our rugged walls and set our reeking clothes steaming in its flicker, but I rolled a stone to the opposite side of the hearth for Editha, and found another for myself, and soon those venison steaks were hissing most invitingly upon the glowing embers, and filling every nook and corner of the Druid slaughter-place with the suggestive fragrance of our supper.

Manners were rude and ready in that time. We supped as well and conveniently that night, carving the meat with the little weapons at our girdles, and eating with our fingers, as though we sat in state at the high thane’s table of distant Voewood and looked down the great rushy hall upon three hundred feeding serfs and bondsmen. And Editha laughed and chattered—secure in my protection—and I echoed her merriment, while now and then my thoughts would wander, and I heard again in the tempest’s whistling the scream of the hungry kites who had seen me die, and in the lashing of the branches the clamor and the beating of the British tribesmen who many a long lifetime before had shouted around this very place to drown my dying yells.

The good food and the warmth and a long day’s work soon brought my fair mistress’s head upon her hand, and presently she was lying upon the withered leaves in the corner, a fair white flower shut up for the night-time. So I finished the steak and divided the remnants between the dogs, and lay back very well contented. But here only commences the strangest part of that evening!

I had warmed my cross-gartered, buskined Saxon legs by the blaze for the best part of an hour, thinking over all the strange episodes of my coming to these ancient isles, and seeing again, on the blank hither wall, this very circle all aglow with the splendid color of its barbarous purpose, the mighty concourse of the Britons set in the greenery of their reverent oaks—the onset of the Romans, the flash and glitter of their close-packed ranks, and the gallant Sempronius—alas! that so good a youth should be reduced to dust—and thus, I suppose, I dozed.

And then it seemed all on a sudden a mighty gust of wind swept down upon the flat roof overhead, shaking even that ponderous stone—those fierce and brawny hounds of mine howled most fearfully—crouching behind with bristling hair and shaking limbs—and, looking up, there—strange, incredible as you will pronounce it—seated beyond the fire on the stone the Saxon had so lately left, drawing her wild, rain-wet British tresses through her supple fingers—calm, indifferent, happy—gazing upon me with the gentle wonder I had seen before, was Blodwen, once again herself!

Need it be said how wild and wonderful that winsome apparition seemed in that uncouth place, how the hot flush of wonder burned upon my swart and weathered cheeks as I sat there and glared through the leaping flame at that pallid outline? Absently she went on with her rhythmical combing, bewitching me with her unearthly grace and the tender substance of her immaterial outline, and as I glowered with never a ready syllable upon my idle tongue, or any emotion but wonder in the heart beating tumultuously under my hunter tunic, the dogs lay moaning behind me, and the wild fantastic uproar of the tempest outside forced through the clefts of our retreat the rain-streaks that sparkled and hissed in the fire-heap.

That time I did not fear, and presently the Princess looked up and said, in a faint, distant voice, that was like the sound of the breeze among seashore pine-trees:

“Well done, my Phœnician! Your courage gives me strength.” And as she spoke the words seemed gradually clearer and stronger, until presently they came sweeter to me than the murmur of a sunny river—gentler than the whispers of the ripe corn and the south wind.

“Shade!” I said. “Wonderful, immaterial, immortal, whence came you?”

“Whence did I come?” she answered, with the pretty reflection of a smile upon her face. “Out of the storm, O son of Anak!—out of the wild, wet night-wind!”

“And why, and why—to stir me to my inmost soul, and then to leave me?”

“Phœnician,” she said, “I have not left you since we parted. I have been the unseen companion of your goings—I have been the shadowless watcher by your sleep. Mine was the unfelt hand that bore your chin up when you swam with the Christian slave-girl—mine was the arm that has turned, invisibly, a hundred javelins from you—and to-night I am come, by leave of circumstance, thus to see you.”

“I should have thought,” I said, becoming now better at my ease, “that one like you might come or go in scorn of circumstances.”

“Wherein, my dear master, you argue with more simplicity than knowledge. There are needs and necessities to the very verge of the spheres.”

But when I questioned what these were, asking the secret of her wayward visits, she looked at the sleeping Editha, and said I could not understand.

“Yes, by Wodin’s self! but I think I can. Yon fair-cheeked girl helps you. There are a hundred turns and touches in your ways and manners that speak of her, and show whence you got that borrowed life.”

“You are astute, my Saxon thane, and I will not utterly refute you.”

“Then, if you can do this, how was it, Blodwen, you never came when I was Roman?”

“In truth, I often tried,” she said, with something like a sigh, “but Numidea was not good to fit my subtle needs, and the other one, Electra, was all beyond me.” And here that versatile shadow threw herself into an attitude, and there before me was the Roman lady, so sweet, so enticing, that my heart yearned for her—ah! for the queenly Electra!—all in a moment. But before I could stretch out my arms the airy form had whisked her ethereal draperies toga-wise across her breast, and had risen, and there, towering to the low roof, flashing down scorn and hatred on me, quaking at her feet, shone the very semblance of Electra as I saw her last in the queenly glamour of her vengeance.

“Yes,” said Blodwen, resuming her own form with perfect calmness before I, astounded, could catch my breath, and stroking out the tangles of her long red hair, “there was no doing anything with her, and so, Phœnician, I could not get translated to your material eyes.”

All this was very wonderful, yet presently we were chatting as though there were naught to marvel at. Many were the things we spoke of, many were the wonders that she hinted at, and as she went my curiosity blazed up apace.

“And, fair Princess,” I said presently, “turner of javelins, favorer of mortals, is it then within the power of such as yourself to rule the destiny of us material ones?”

“Not so; else, Phœnician, you were not here!”

This made me a little uncomfortable, but, nothing daunted, I looked the strangest visitor that ever paid a midnight visit full in the face, and persisted: “Tell me, then, you bright reflection of her I loved, how seems this tinsel show of life upon its over side? Is it destiny or man that is master? How looks the flow of circumstances to you?—to us, you will remember, it is vague, inexplicable.”

“You ask me more than I can say,” she answered, “but so far I will go—you, material, live substantially, and before you lies unchecked the illimitable spaces of existence. Of all these you are certain heir.”

“Speak on!” I cried, for now and then her voice and attention flagged. “And is there any rule or sequence in this life of ours—is it for you to guide or mend our happenings?”

“No, Phœnician! You are yourselves the true forgers of the chains that bind you, and that initial ’prenticeship you serve there on your world is ruled by the aggregate of your actions. I tell you, Tyrian,” she exclaimed, with something as much like warmth as could come from such a hazy air-stirred body—“I tell you nothing was ever said or done but was quite immortal; all your little goings and comings, all your deeds and misdeeds, all the myriad leaves of spoken things that have ever come upon the forests of speech, all the rain-drops of action that have gone to make the boundless ocean of human history, are on record. You shake your head, and cannot understand? Perhaps I should not wonder at it.”

“And have all these things left a record upon the great books of life, and is it given to the beings of the air to refer to them, even as yonder hermit finds secreted on his yellow vellums the things of long ago?”

“It is so in some kind. The actions of that life of yours leave spirit-prints behind them from the most infinitesimal to the largest. Now, see! I have but to wish, and there again is all the moving pantomime around you of that unhappy day when you well-nigh died upon this spot,” and the chieftainess leaped to her feet and swept her arm around and looked into the void and smiled and nodded as though all the wild spectacle she spoke of were enacting under her very eyes. “Surely, you see it! Look at the priests and the people, and there the running foreigners and that tall youth at their head—why, O trader in oils and dyes! it is not the remembrance of the thing, it is, I swear it, the thing itself——”

But never a line or color could I perceive, only the curling smoke overhead looped and hung like tapestries upon the gray lichened walls, and the black night-time through the crevices. And, discovering this, Blodwen suddenly stopped and looked upon me with vexed compassion. “I am sorry, I am no good teacher to so outrun my pupil. Ask me henceforth what simple questions you will, and they shall be answered to the best I can.”

And so presently I went on: “If those things which have been are thus to you—and it does not seem impossible—how is it with those other things of to-day, or still unborn of the future? How far can you more favored ones foresee or guide those things to which we, unhappy, but submit?”

“The strong tide of circumstance, Phœnician, is not to be turned by such hands as these”—and she held her pallid wrists toward the blaze, until I saw the ruddy gleam flash back from the rough gold bosses of her ancient bracelets. “There are laws outside your comprehension which are not framed for your narrow understanding. We obey these as much as you, but we perceive with infinitely clearer vision the inevitable logic of fate, the true sequence of events, and thus it is sometimes within our power to amend and guide the details of that brief episode which you call your life.”

“Do you say that priceless span, my comrades, yonder sleeping girl, and all the others set so high a value on is but ‘an episode’?”

“Yes—a halting step upon a wondrous journey, half a gradation upon the mighty spirals of existence!”

“And time?” I asked, full of a wonder that scarce found leisure to comprehend one word of hers before it asked another question. “Is there time with you? Even I, reflective now and then upon this long journey of mine, have thought that time must be a myth, an impossibility to larger experience.”

“Of what do you speak, my merchant? I do not remember the word.”

“Oh, yes; but you must. Is there period and change yonder? Is Time—Time, the great braggart and bully of life, also potent with you?”

“Ah! now I do recall your meaning; but, my Tyrian, we left our hour-glasses and our calendars behind us when we came away! There is, perhaps, time yonder to some extent, but no mortal eyes, not mine even, can tell the teaching of that prodigious dial that records the hours of universes and of spaces.”

I bent my head and thought, for I dimly perceived in all this a meaning appearing through its incomprehensibleness. Much else did we talk through the live-long night, whereof all I may not tell, and something might but weary you. At one time I asked her of the little one I had never seen, and then she, reflective, questioned whether I would wish to see him. “As gladly,” was my reply, “as one looks for the sun in springtime.” At this the comely chieftainess seemed to fall a-musing, and even while she did so an eddy in the curling smoke of the low red fire swung gently into consistency there by her bare shoulder, and brightened and grew into mortal likeness, and in a moment, by the summons of his mother’s will, from where I knew not, and how I could not guess, a fair, young, ruddy boy was fashioned and stood there leaning upon the gentle breast that had so often rocked him, and gazing upon me with a quiet wonder that seemed to say, “How came you here?” But the little one had not the substance of the other, and after a moment, during which I felt somehow that no slight effort was being made to maintain him, he paled, and then the same waft of air that had conspired to his creation shredded him out again into the fine thin webs of disappearing haze.

Comely shadow! Dear British mistress! Great was thy condescension, passing strange thy conversation, wonderful thy knowledge, perplexing, mysterious thy professed ignorance! And then, when the morning was nigh, she bade me speak a word of comfort to the restless-sleeping Editha, and when I had done so I turned again—and the cave was empty! I ran out into the open air and whispered “Blodwen!” and then louder “Blodwen!” and all those gray, uncouth, sinful old monoliths, standing there in the half-light up to their waists in white mist, took up my word and muttered out of their time-worn hollows one to another, “Blodwen, Blodwen!” but never again for many a long year did she answer to that call.