CHAPTER VIII

It was with indescribable sensations of mingled pain and satisfaction that life dawned again in my mind and body after the drowsy ending of the last chapter. To me the process was robbed of wonder—no idea crossed my mind but that I had slept an ordinary sleep; but to you, knowing the strange fate to which I am liable, will at once occur suspicion and expectation. Both these feelings will be gratified, yet I must tell my story, in my simple fashion, as it occurred.

This time, then, wakefulness came upon me in a prolonged gray and crimson vision; and for a long spell—now I think of it closely—probably for days, I was wrestling to unravel a strange web of light and gloom, in which all sorts of dreamy colors shone alternate in a misty blending upon the blank field of my mind. These colors were now and again swallowed up by an episode of deep obscurity, and the longer I studied them in an unwitting, listless way the more pronounced and definite they became, until at last they were no more a tinted haze of uncertain tone, but a checkered plan, silently passing over my shut eyelids at slow, measured intervals. Well, upon an afternoon—which, you will understand, I shall not readily forget—my eyes were suddenly opened, and, with a deep sigh, like one who wakes after a good night’s repose, existence came back upon me, and, all motionless and dull, but very consciously alive and observant, I was myself again.

My first clear knowledge on that strange occasion was of the strains of a merle singing somewhere near; and, as those seraphic notes thrilled into the dry, unused channels of my hearing, the melody went through me to my utmost fiber. Next I felt, as a strong tonic elixir, a draught of cool spring air, full of the taste of sunshine and rich with the scent of a grateful earth, blowing down upon me and dissipating, with its sweet breath, the last mists of my sleepfulness. While these soft ministrations of the good nurse Nature put my blood into circulation again, filling me with a gentle vegetable pleasure, my newly opened eyes were astounded at the richness and variety of their early discoverings.

To the inexperience of my long forgetfulness everything around was quaint and grotesque! Everything, too, was gray, and crimson, and green. As I stared and speculated, with the vapid artlessness of a baby novice, the new world into which I was thus born slowly took form and shape. It opened out into unknown depths, into aisles and corridors, into a wooden firmament overhead, checkered with clouds of timber-work and endless mazes (to my poor untutored mind) of groins and buttresses. Long gray walls—the same that had been the groundwork of my fancy—opened on either side, a great bare sweep of pavement was below them, and a hundred windows letting in the comely daylight above, but best of all was that long one by me which the crimson sun smote strongly upon its varied surface, and, gleaming through the gorgeous patchwork of a dozen parables in colored glasses, fell on the ground below in pools of many-colored brightness. As I, inertly, watched these shifting beams, I perceived in them the cause of those gay mosaics with which the outer light had amused my sleeping fancies!

All these things in time appeared distinct enough to me, and tempted a trial of whether my physical condition equaled the apparent soundness of my senses. I had hardly had leisure as yet to wonder how I had come into this strange position, or to remember—so strong were the demands of surrounding circumstances on my attention—the last remote pages of my adventures—remote, I now began to entertain a certain consciousness, they were—I was so fully taken up with the matter of the moment, that it never occurred to me to speculate beyond, but the pressing question was in what sort of a body were those sparks of sight and sense burning.

It was pretty clear I was in a church, and a greater one than I had ever entered before. My position, I could tell, spoke of funeral rites, or rather the stiff comfort of one of those marble effigies with which sculptors have from the earliest times decorated tombs. And yet I was not entombed, nor did I think I was marble, or even the plaster of more frugal monumenters. My eyes served little purpose in the deepening light, while as yet I had not moved a muscle. As I thought and speculated, the dreadful fancy came across me that, if I were not stone, possibly I was the other extreme—a thin tissue of dry dust held together by the leniency of long silence and repose, and perhaps—dreadful consideration!—the sensations of life and pleasure now felt were threading those thin wasted tissues, as I have seen the red sparks reluctantly wander in the black folds of a charred scroll, and finally drop out one by one for pure lack of fuel. Was I such a scroll? The idea was not to be borne, and, pitting my will against the stiffness of I knew not what interval, I slowly lifted my right arm and held it forth at length.

My chief sentiment at the moment was wonderment at the limb thus held out in the dim cathedral twilight, my next was a glow of triumph at this achievement, and then, as something of the stress of my will was taken off and the arm flew back with a jerk to its exact place by my side, a flood of pain rushed into it, and with the pain came slowly at first, but quickly deepening and broadening, a remembrance of my previous sleeps and those other awakenings of mine attended by just such thrills.

I will not weary you with repetitions or recount the throes that I endured in attaining flexibility. I have, by Heaven’s mercy, a determination within me of which no one is fit to speak but he who knows the extent and number of its conquests. A dozen times, so keen were these griefs, I was tempted to relinquish the struggle, and as many times I triumphed, the unquenched fire of my mind but burning the brighter for each opposition.

At last, when the painted shadows had crept up the opposite wall inch by inch and lost themselves in the upper colonnades, and the gloom around me had deepened into blackness, I was victorious, and weak, and faint, and tingling; but, respirited and supple, I lay back and slept like a child.

The rest did me good. When I opened my eyes again it was with no special surprise (for the capacity of wonder is very volatile) that I saw the chancel where I lay had been lighted up, and that a portly Abbot was standing near, clad in brown fustian, corded round his ample middle, and picking his teeth with a little splinter of wood as he paced up and down muttering to himself something, of which I only caught such occasional fragments as “fat capons,” “spoiled roasts” (with a sniff in the direction of the side door of the abbey), and a malison on “unseemly hours” (with a glance at an empty confessional near me), until he presently halted opposite—whereon I immediately shut my eyes—and regarded me with dull complacency.

As he did so an acolyte, a pale, grave recluse on whose face vigils and abnegation had already set the lines of age, stepped out from the shadow, and, standing just behind his superior, also gazed upon me with silent attention.

“That blessed saint, Ambrose,” said the fat Abbot, pointing at me with his toothpick, apparently for want of something better to speak about, “is nearly as good to us as the miraculous cruse was to the woman of Sarepta: what this holy foundation would do just now, when all men’s minds are turned to war, without the pence we draw from pilgrims who come to kneel to him, I cannot think!”

“Indeed, sir,” said the sad-eyed youth, “the good influence of that holy man knows no limit: it is as strong in death as no doubt it was in life. ’Twas only this morning that by leave of our Prior I brought out the great missals, and there found something, but not much, that concerned him.”

“Recite it, brother,” quoth the Abbot with a yawn, “and if you know anything of him beyond the pilgrim pence he draws you know more than I do.”

“Nay, my Lord, ’tis but little I learned. All the entries save the first in our journals are of slight value, for they but record from year to year how this sum and that were spent in due keeping and care of the sleeping wonder, and how many pilgrims visited this shrine, and by how much Mother Church benefited by their dutiful generosity.”

“And the first entry? What said it?”

“All too briefly, sir, it recorded in a faded passage that when the saintly Baldwin—may God assoil him!” quoth the friar, crossing himself—“when Baldwin, the first Norman Bishop in your Holiness’s place, came here, he found yon martyr laid on a mean and paltry shelf among the brothers’ cells. All were gone who could tell his life and history, but your predecessor, says the scroll, judging by the outward marvel of his suspended life, was certain of that wondrous body’s holy beatitude, and, reflecting much, had him meetly robed and washed, and placed him here. ’Twas a good deed,” sighed the studious boy.

“Ah! and it has told to the advantage of the monastery,” responded his senior, and he came close up and bent low over me, so that I heard him mutter, “Strange old relic! I wonder how it feels to go so long as that—if, indeed, he lives—without food. It was a clever thought of my predecessor to convert the old mummy-bundle of swaddles into a Norman saint! Baldwin was almost too good a man for the cloisters; with so much shrewdness, he should have been a courtier!”

“Oh!” I thought, “that is the way I came here, is it, my fat friend?” and I lay as still as any of my comrade monuments while the old Abbot bent over me, chuckling to himself a bibulous chuckle, and pressing his short, thick thumb into my sides as though he was sampling a plump pigeon or a gosling at a village fair.

“By the forty saints that Augustine sent to this benighted island, he takes his fasting wonderfully well! He is firm in gammon and brisket—and, by that saintly band, he has even a touch of color in his cheeks, unless these flickering lights play my eyes a trick!” whereupon his Reverence regarded me with lively admiration, little witting it was more than a breathless marvel, a senseless body, he was thus addressing.

In a moment he turned again: “Thou didst not tell me the date of this old fellow’s—Heaven forgive me!—of this blessed martyr’s sleep. How long ago said the chronicles since this wondrous trance began?”

“My Lord, I computed the matter, and here, by that veracious, unquestionable record, he has lain three hundred years and more!”

At this extraordinary statement the portly Abbot whistled as though he were on a country green, and I, so startling, so incredulous was it, involuntarily turned my head toward them, and gathered my breath to cast back that audacious lie. But neither movement nor sign was seen, for at that very moment the quiet novice laid a finger upon the monk’s full sleeve and whispered hurriedly, “Father!—the Earl—the Earl!” and both looked down the chancel.

At the bottom the door swung open, giving a brief sight of the pale-blue evening beyond, and there entered a tall and martial figure who advanced in warlike harness to the altar steps, and, placing down the helm decked with plumes that danced black and visionary in the dim cresset light, he fell upon one knee.

“Pax vobiscum, my son!” murmured the Abbot, extending his hands in blessing.

“Et vobis,” answered the gallant, “da mihi, domine reverendissime, misericordiam vestram!” And at the sound of their voices I raised me to my elbow, for the young warlike Earl, as he bent him there, was sheathed and armed in a way that I, though familiar with many camps, had never seen before.

Over his fine gold hauberk was a wondrous tabard, a magnificent emblazoned surtout, and, as he knelt, the light of the waxen altar tapers twinkled upon his steel vestments, they touched his yellow curls and sparkled upon the jeweled links of the chain he had about his neck; they gleamed from breast-plate and from belt; they illuminated the thick-sown pearls and sapphires of his sword-hilt, and glanced back in subdued radiance, as befited that holy place, from gauntlets and gorget, from warlike furniture and lordly gems, down to the great rowels of the golden spurs that decked his knightly heels.

The acolyte had shrunk into the shadows, and the Earl had had his blessing, when the Abbot drew him into the recess where I lay in the moonbeams, that he might speak him the more privately—that Churchman little guessing what a good listener the stern, cold saint, so trim and prone upon his marble shrine, could be!

“Ah, noble Codrington,” quoth the monk, “truly we will to the confessional at once, since thou art in so much haste, and thou shalt certainly travel the lighter for leaving thy load of transgressions to the holy forgiveness of Mother Church; but first, tell me true, dost thou really sail for France to-night?”

“Holy father, at this very moment our vessels are waiting to be gone, and all my good companions chafe and vex them for this my absence!”

“What! and dost thou start for hostile shores and bloody feuds with half thy tithes and tolls unpaid to us? Noble Earl, wert thou to meet with any mischance yonder—which Heaven prevent!—and didst thou stand ill with our exchequer in this particular, there were no hope for thee! I tell thee thou wert as surely damned if thou diedst owing this holy foundation aught of the poor contributions it asks of those to whom it ministers as if thy life were one long count of wickedness! I will not listen—I will not shrive thee until thou hast comported thyself duly in this most important particular!”

“Good father, thy warmth is unnecessary,” replied the Earl. “My worldly matters are set straight, and my steward has orders to pay thee in full all that may be owing between us; ’twas spiritual settlement I came to seek.”

“Oh!” quoth his Reverence, in an altered tone. “Then thou art free at once to follow the promptings of thy noble instinct, and serve thy King and country as thou listest. I fear this will be a bloody war you go to.”

“’Tis like to be,” said the soldier, brightening up and speaking out boldly on a subject he loved, his fine eyes flashing with martial fire—“already the yellow sun of Picardy flaunts on Edward’s royal lilies!”

“Ah,” put in the monk, “and no doubt ripens many a butt of noble malmsey.”

“Already the red soil of Flanders is redder by the red blood of our gallant chivalry!”

“Yet even then not half so red, good Earl, as the ripe brew of Burgundy—a jolly mellow brew that has stood in the back part of the cellar, secure in the loving forbearance of twenty masters. Talk of renown—talk of thy leman—talk of honor and the breaking of spears—what are all these to such a vat of beaded pleasures? I tell thee, Codrington, not even the fabled pool wherein the rhymers say the cursed Paynim looks to foretaste the delights of his sinful heaven reflects more joy than such a cobwebbed tub. Would that I had more of them!” added the bibulous old priest after a pause, and sighing deeply. As he did so an idea occurred to him, for he exclaimed, “Look thee, my gallant boy! Thou art bound whither all this noble stuff doth come from, and ’tis quite possible in the rough and tumble of bloody strife thou may’st be at the turning inside out of many a fat roost and many a well-stocked cellar. Now, if this be so, and thou wilt remember me when thou seest the gallant drink about to be squandered on the loose gullets of base, scullion troopers, why then ’tis a bargain, and, in paternal acknowledgment of this thy filial duty, I will hear thy confession now, and thy penance, I promise, shall not be such as will inconvenience thine active life.”

The knight bent his head, somewhat coldly I thought, and then they turned and went over to the oriel confessional, where the moonlight was throwing from the window above a pallid pearly transcript of the Mother and her sweet Nazarene Babe, all in silver and opal tints, upon the sacred woodwork, and as the priest’s black shadow blotted the tender picture out I heard him say:

“But mind, it must be good and ripe—’tis that vintage with the two white crosses down by the vent that I like best—an thou sendest me any sour Calais layman tipple, thou art a forsworn heretic, with all thy sin afresh upon thee—so discriminate,” and the worthy Churchman entered to shrive and forgive, and as the casement closed upon him the sweet, silent, indifferent shadows from above blossomed again upon the doorway.

Dreamy and drowsy I lay back and thought and wondered, for how long I know not, but for long—until the dim aisles had grown midnight-silent and the moon had set, and then an owl hooted on the ledges outside, and at that sound, with a start and a sigh, I awoke once more.

“Fools!” I muttered, thinking over what I had heard with dreamy insequence—“fools, liars, to set such a date upon this rest of mine! Drunken churls! I will go at once to my fair Saxon, to my sweet nestlings—that is, if they be not yet to bed—and to-morrow I will give that meager acolyte such a lesson in the misreading of his missal-margins as shall last him till Doomsday. By St. Dunstan! he shall play no more pranks with me—and yet, and yet, my heart misgives me—my soul is loaded with foreboding, my spirit is sick within me. Where have I come to? Who am I? Gods! Hapi, Amenti of the golden Egyptian past, Skogula, Mista of the Saxon hills and woods, grant that this be not some new mischance—some other horrible lapse!” and I sat up there on the white stone, and bowed my head and dangled my apostolic heels against my own commemorative marbles below, while gusts of alternate dread and indignation swept through the leafless thickets of remembrance.

Presently these meditations were disturbed by some very different outward sensations. There came stealing over the consecrated pavements of that holy pile the sound of singing, and it did not savor of angelic harmony; it was rough, and jolly, and warbled and tripped about the columns and altar steps in most unseemly sprightliness. “Surely never did St. Gregory pen such a rousing chorus as that,” I thought to myself, as, with ears pricked, I listened to the dulcet harmonies. And along with the music came such a merry odor as made me thirsty to smell of it. ’Twas not incense—’twas much more like cinnamon and nutmegs—and never did censer—never did myrrh and galbanum smell so much of burnt sack and roasted crab-apples as that unctuous, appetizing taint.

I got down at once off my slab, and, being mighty hungry, as I then discovered, I followed up that trail like a sleuth-hound on a slot. It was not reverent, it did not suit my saintship, but down the steps I went hot and hungry, and passed the reredos and crossed the apse, and round the pulpit, and over the curicula, and through the aisles, and by many a shrine where the tapers dimly burned I pressed, and so, with the scent breast high, I flitted through an open archway into the checkered cloisters. Then, tripping heedlessly over the lettered slabs that kept down the dust of many a roystering abbas, I—the latest hungry one of the countless hungry children of time—followed down that jolly trail, my apostolic linens tucked under my arm, jeweled miter on a head more accustomed to soldier wear, and golden crook carried, alas! like a hunter lance “at trail” in my other hand, till I brought the quest to bay. At the end of the cloisters was a door set ajar, and along by the jamb a mellow streak of yellow light was streaming out, rich with those odors I had smelled and laden with laughter and the sound of wine-soaked voices noisy over the end, it might be, of what seemed a goodly supper. I advanced to the light, listened a moment, and then in my imperious way pushed wide the panel and entered.

It was the refectory of the monastery, and a right noble hall wherein ostentation and piety struggled for dominion. Overhead the high peaked ceiling was a maze of cunningly wrought and carved woodwork, dark with time and harmonized with the assimilating touches of age. Round by the ample walls right and left ran a corridor into the dim far distance; and crucifix and golden ewer, cunning saintly image, and noble-branching silver candlesticks, gleamed in the dusk against the ebony and polish of balustrade and paneling. Under the heavy glow of all these things the Brothers’ bare wooden table extended in long demure lines; but wooden platter and black leathern mugs were now all deserted and empty.

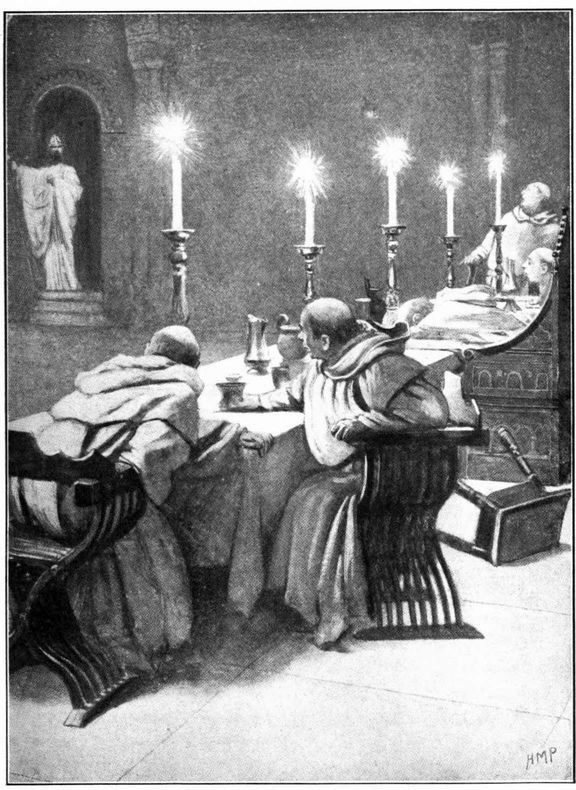

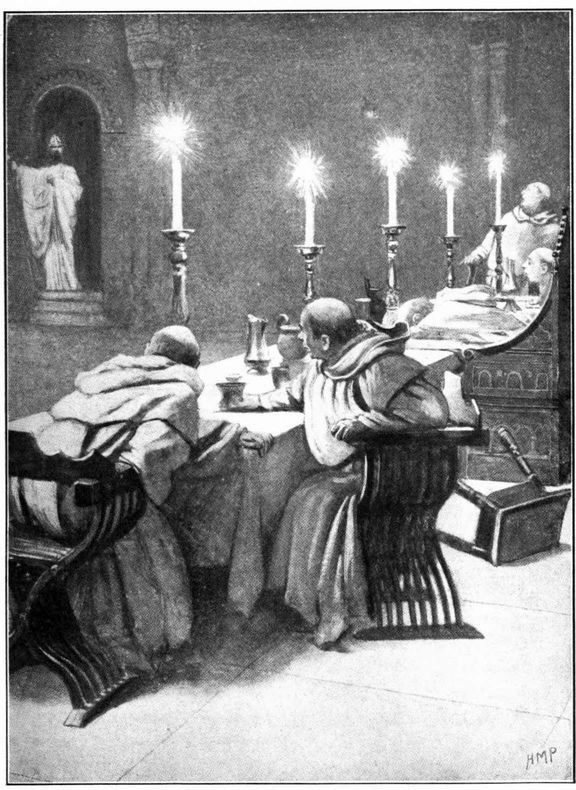

It was from the upper end came the light and jollity. Here a wider table was placed across the breadth of the hall, and upon it all was sumptuous magnificence—holy poverty here had capitulated to priestly arrogance. Silver and gold, and rare glasses from cunning Italian molds, enriched about with shining enamels wherein were limned many an ancient heathen fancy, shone and sparkled on that monkish board. On either side, in mighty candelabra, bequeathed by superstition and fear, there twinkled a hundred waxen candles, and up to the flames of these steamed, as I looked, many a costly dish uncovered, and many a mellow brew beaded and shining to the very brim of those jeweled horns and beakers that were the chief accessories to that pleasant spread.

They who sat here seemed, if a layman might judge, right well able to do justice to these things. Half a dozen of them, jolly, rosy priors and prelates, were round that supper table, rubicund with wine and feeding, and in the high carved chair, coif thrown back from head, his round, ruddy face aflush with liquor, his fat red hand asprawl about his flagon, and his small eyes glazed and stupid in his drunkenness, sat my friend the latest Abbot of St. Olaf’s fane.

He had been singing, and, as I entered, the last distich died away upon his lips, his round, close-cropped head, overwhelmed with the wine he loved so much, sank down upon the table, the red vintage ran from the overturned beaker in a crimson streak, and while his boon comrades laughed long and loud his holiness slept unmindful. It was at this very moment that I entered, and stood there in my ghostly linen, stern and pale with fasting, and frowning grimly upon those godless revelers. Jove! it was a sight to see them blanch—to see the terror leap from eye to eye as each in turn caught sight of me—to see their jolly jaws drop down, and watch the sickly pallor sweeping like icy wind across their countenances. So grim and silent did we face each other in that stern moment that not a finger moved—not a pulse, I think, there beat in all their bodies, and in that mighty hall not a sound was heard save the drip, drip of the Abbot’s malmsey upon the floor and his own husky snoring as he lay asleep amid the costly litter of his swinish meal.

Stern, inflexible, there by the black backing of the portal I frowned upon them—I, whom they only deemed of as a saint dead three hundred years before—I, whom lifeless they knew so well, now stood vengeful upon their threshold, scowling scorn and contempt from eyes where no life should have been—can you doubt but they were sick at heart, with pallid cheeks answering to coward consciences? For long we remained so, and then, with a wild yell of terror they were all on foot, and, like homing bats by a cavern mouth, were scrambling and struggling into the gloom of the opposite doorway. I let them escape, then, stalking over to the archway, thrust the wicket to upon the heels of the last flyer, and glad to be so rid of them, shot the bolt into the socket and barred that entry.

Stern, inflexible, I frowned upon them

Then I went back to my friend the Abbot, and stood, reflective, behind him, wondering whether it were not a duty to humanity to rid it of such a knave even as he slept there. But while I stood at his elbow contemplating him, the unwonted silence told upon his dormant faculties, and presently the heavy head was raised, and, after an inarticulate murmur or two, he smiled imbecilely, and, picking up the thread of his revelry, hiccoughed out: “The chorus, good brothers!—the chorus—and all together!”

Die we must, but let us die drinking at an inn.

Hold the winecup to our lips sparkling from the bin!

So, when angels flutter down to take us from our sin,

“Ah! God have mercy on these sots!” the cherubs will begin.

“Why, you rogues!” he said, as his drunken melody found no echo in the great hall—“why, you sleepy villains! am I a strolling troubadour that I should sing thus alone to you?” And then, as his bleared and dazzled eyes wandered round the empty places, the spilled wine and overturned trestles, he smiled again with drunken cunning. “Ah!” he muttered; “then they must be all under the tables! I thought that last round of sack would finish them! Hallo, there! Ambrose! De Vœux! Jervaulx! Jolly comrades!—sleepy dogs! Come forth! Fie on ye!—to call yourselves good monks, and yet to leave thy simple, kindly Prior thus to himself!” and he pulled up the table linen and peered below. Sorely was the Churchman perplexed to see nothing; and first he glared up among the oaken rafters, as though by chance his fellows had flown thither, and then he stared at the empty places, and so his gaze wandered round, until, in a minute or two, it had made the complete circle of the place, and finally rested on me, standing, immovable, a pace from his elbow.

At first he stared upon me with vapid amusement, and then with stupid wonder. But it was not more than a second or two before the truth dawned upon that hazy intellect, and then I saw the thick, short hands tighten upon the carving of his priestly throne, I saw the wine flush pale upon his cheeks, and the drunken light in his eyes give place to the glare of terror and consternation. Just as they had done before him, but with infinite more intensity, he blanched and withered before my unrelenting gaze, he turned in a moment before my grim, imperious frown, from a jolly, rubicund old bibber, rosy and quarrelsome with his supper, into a cadaverous, sober-minded confessor, lantern-jawed and yellow—and then with a hideous cry he was on foot and flying for the doorway by which his friends had gone! But I had need of that good confessor, and ere he could stagger a yard the golden apostolic crook was about the ankle of the errant sheep, and the Prior of St. Olaf’s rolled over headlong upon the floor.

I sat down to supper, and as I helped myself to venison pasty and malmsey I heard the beads running through the recumbent Abbot’s fingers quicker than water runs from a spout after a summer thunder shower. “Misericordia, Domine, nobis!” murmured the old sinner, and I let him grovel and pray in his abject panic for a time, then bade him rise. Now, the fierceness of this command was somewhat marred, because my mouth was very full just then of pasty crust, and the accents appeared to carry less consternation into my friend’s heart than I had intended. The paternoster began to run with more method and coherence, and, soon finding he was not yet halfway to that nether abyss he had seen opening before him, he plucked up a little heart of grace. Besides, the avenger was at supper, and making mighty inroads into the provender the Abbot loved so well: this took off the rough edge of terror, and was in itself so curious a phenomenon that little by little, with the utmost circumspection, the monk raised his head and looked at me. I kept my baleful eyes turned away, and busied me with my loaded platter—which, by the way, was far the most interesting item of the two—and so by degrees he gained confidence, and came into a sitting position, and gazed at the hungry saint, so active with the victuals, wonder and awe playing across his countenance. “I see, Sir Priest,” I said, “you have a good cook yonder in the buttery,” but the Abbot was as yet too dazed to answer, so I went on to put him more at his ease (for I designed to ask him some questions later on), “now, where I come from, the great fault of the cooks is, they appreciate none of your Norman niceties—they broil and roast forever, as though every one had a hunter appetite, and thus I have often been weary of their eternal messes of pork and kine.”

“Holy saints!” quoth the Abbot. “I did not dream you had any cooks at all.”

“No cooks! Thou fat wine-vat, what, didst thou think we ate our viands raw?”

“Heaven forbid!” the Abbot gasped. “But, truly, your sanctity’s experiences astound me! ’Tis all against the canons. And if they be thus, as you say, at their trenchers, may I ask, in all humbleness and humility, how your blessed friends are at their flagons?”

“Ah! Sir, good fellows enough my jolly comrades, but caring little for thy red and purple vintages, liking better the merry ale that autumn sends, and the honeyed mead, yet in their way as merry roysterers for the most part as though they were all Norman Abbots,” I said, glancing askance at him.

By this time the Prior was on his feet, as sober as could be, but apparently infinitely surprised and perplexed at what he saw and heard. He cogitated, and then he diffidently asked: “An it were not too presumptive, might I ask if your saintship knows the blessed Oswald?”

“Not I.”

“Nor yet the holy Sewall de Monteign?” he queried with a sigh—“once head of these halls and cells.”

“Never heard of him in my life.”

“Nor yet of Grindal? or Gerard of Bayeux? or the saintly Anselm, my predecessor in that chair you fill?” groaned the jolly confessor.

“I tell you, priest, I know none of them—never heard their names or aught of them till now.”

“Alas! alas!” quoth the monk, “then if none of these have won to heaven, if none of these are known to thee so newly thence, there can be but small hope for me!” And his fat round chin sank upon his ample chest, and he heaved a sigh that set the candles all a-flickering halfway down the table.

“Why, priest, what art thou talking of?—Paradise and long-dead saints? ’Twas of the Saxons—Harold’s Saxons—my jolly comrades and allies in arms when last in life, I spoke.”

“Ho! ho! Was that so? Why, I thought thou wert talking of things celestial all this while, though, in truth, thy speech sorted astounding ill with all I had heard before!”

“I think, Father,” I responded, “there is more burnt sack under thy ample girdle than wit beneath thy cowl. But never mind, we will not quarrel. Sit down, fill yon tankard (for dryness will not, I fancy, improve thy eloquence), and tell me soberly something of this nap of mine.”

“Ah, but, Sir, I was never very good at such studious work,” the monk replied, seating himself with uneasy obedience: “if I might but fetch in our Clerk—though, in truth, I cannot imagine why and whither he has gone—he is one who has by heart the things thou wouldst know.”

“Stir a foot, priest,” I said, with feigned anger, “and thou art but a dead Abbot! Tell me so much as your muddled brain can recall. Now, when I supped here before that yellow-skinned Norman William sat upon the English throne——”

“Saints in Paradise! what, he who routed Harold, and founded yonder abbey of Battle—impossible!”

“What, dost thou bandy thy ‘impossible’ with me? Slave, if thou cast again but one atom of doubt, one single iota of thy heretic criticism here, thou shalt go thyself to perdition and seek Sewall de Monteign and Gerard of Bayeux,” and I laid my hand upon my crook.

“Misericordia! misericordia!” stammered the Abbot. “I meant no ill whatever, but the extent of thy Holiness’s astounding abstinence overwhelmed me.”

“Why, then to your story. But I am foolish to ask. You cannot, you dare not, tell me again that lie of thy acolyte, that three hundred years have passed since then. Look up, say ’twas false, and that single word shall unburden here,” and I struck my breast, “a soul of a load of dread and fear heavier than ever was lifted by priestly absolution before.”

But still he hung his face, and I heard him mutter that fifty white-boned Abbots lay in the cloisters, heel to head, and the first one was a kinsman of William’s, and the last was his own predecessor.

“Then, if thou darest not answer this question, who reigns above us now? Has the Norman star set, as I once hoped it might, behind the red cloud of rebellion? or does it still shine to the shame of all Saxons?”

“Sir Saint,” answered the monk, with a little touch of the courage and pride of his race gleaming for a moment through his drunken humility, “rebellion never scared the Norman power—so much I know for certain; and Saxon and Norman are one by the grace of God, linked in brotherhood under the noble Edward. Expurgate thy divergences; erase ‘invaders and invaded’ from thy memory, and drink as I drink —if, indeed, all this be news to thee—for the first time to ‘England and to the English!’”

“Waes hael, Sir Monk—‘England and the English!’”

“Drink hael, good saint!” he answered, giving me the right acceptance of my flagon challenge, “and I do hereby receive thee most paternally into the national fold! Nevertheless, thou art the most perplexing martyr that ever honored this holy fane”—and he raised the great silver cup to his lips and took a mighty pull. Then he gazed reflectively for a moment into the capacious measure, as though the pageantry of history were passing across the shining bottom in fantastic sequence, and looked up and said—“Most wonderful—most wonderful! Why, then, you know nothing of William the Red?”

“The William I knew was red enough in the hands.”

“Ah! but this other one who followed him was red on the head as well, and an Anselm was Archbishop while he reigned.”

“Well, and who came next in thy preposterous tale?”

“Henry Plantagenet—unless all this sack confuses my memory—I have told thee, good saint, I am better at mass and breviar than at missals and scroll.”

“And better, no doubt, than either at thy cellar score-book, priest! But what befell your Henry?”

“Frankly, I am not very certain; but he died eventually.”

“’Tis the wont of kings no less than of lesser folk. Pass me yon bread platter, and fill thy flagon. So much history, I see, makes thee husky and sad!”

“Well, then came Stephen de Blois, the son of Adeliza, who was daughter to the Conqueror.”

“Forsworn priest!” I exclaimed at that familiar name, leaping to my feet and swinging the great gold flail into the air, “that is a falser lie than any yet. The noble Adeliza was troth to Harold, and had no children; unsay it, or——” and here the crook poised ominously over the shrieking Abbot’s head.

“I lied! I lied!” yelled the monk, cowering under the swing of my weapon like a partridge beneath a falcon’s circlings, and then, as the crook was thrown down on the table again, he added: “’Twas Adela, I meant; but what it should matter to thee whether it were Adeliza or Adela passes my comprehension,” and the monk smoothed out his ruffled feathers.

“Proceed! It is not for thee to question. Wrought Stephen anything more notable to thy mind than Henry?”

“Well, Sir, I recall, now thou puttest me to it, that he laid rough hands upon the sacred persons of our Bishops once or twice, yet he was much indebted to them. Didst ever draw sword in a good quarrel, Sir Saint?”

“Didst ever put thy fingers into a venison pasty, Sir Priest? Because, if thou hast, as often, and oftener, have I done according to thy supposition.”

“Why, then, I wonder you lay still upon yonder white marble slab while all the northern Bishops were up in arms for Stephen, and on bloody Northallerton Moor broke the power of the cruel Northmen forever. That day, Sir, the sacred flags of St. Cuthbert of Durham, St. Peter of York, St. John of Beverley, St. Wilfred of Ripon, not to mention the holy Thurstan’s ruddy pennon, led the van of battle. ’Tis all set out in a pretty scroll that we have over the priory fireplace, else, as you will doubtless guess, I had never remembered so much of detail.”

“Anyhow, it is well recalled. Who came next?”

“Another Henry, and he made the saintly Thomas Becket Archbishop in the year of grace 1162, and afterward the holy prelate was gathered to bliss.”

“Thy history is mostly exits and entries, but perhaps it is none the less accurate for all that. And now thou wilt say this Henry was no more lasting than his kinsman—he too died.”

“Completely and wholly, Sir, so that the burly Richard Cœur de Lion reigned in his stead; and then came John, who was at best but a wayward vassal of St. Peter’s Chair.”

“Down with him, jolly Abbot! And mount another on the shaky throne of thy fantastic narrative. I am weary of the succession already, and since we have come so far away from where I thought we were I care for no great niceties of detail. Put thy Sovereigns to the amble, make them trot across the stage of thy hazy recollection, or thou wilt be asleep before thou canst stall and stable half of them.”

“Well, then, a Henry came after John, and an Edward followed him—then another of the name—and then a third—that noble Edward in whose sway the realm now is, and in whom (save some certain exactions of rent and taxes) Mother Church perceives a glorious and a warlike son. But it is a long muster roll from the time of thy Norman monarch to this year of grace 1346.”

“A long roll!” I muttered to myself, turning away from my empty plate—“horrible, immense, and vast! Good Lord! what shadows are these men who come and go like this! Wonderful and dreadful! that all those tinseled puppets of history—those throbbing epitomes of passion and godlike hopes—should have budded, and decayed, and passed out into the void, finding only their being, to my mind, in the shallow vehicle of this base Churchman’s wine-vault breath. Dreadful, quaint, abominable! to think that all these flickering human things have paced across the sunny white screen of life—like the colored fantasies yonder stained windows threw upon my sleeping eyes—and yet I only but wake hungry and empty, unchanged, unmindful, careless!—Priest!” I said aloud, so sudden and fiercely that the monk leaped to his feet with a startled cry from the drunken sleep into which he had fallen—“priest! dost fear the fires of thy purgatory?”

“Ah, glorious miracle! but—but surely thou wouldst not——”

“Why, then, answer me truly, swear by that great crucified form there shining in the taper light above thy throne, swear by Him to whom thou nightly offerest the hyssop incense of thy beastly excesses—swear, I say!”

“I do—I do!” exclaimed St. Olaf’s priest in extravagant terror, as I towered before him with all my old Phrygian fire emphasized by the sanctity of my extraordinary repute. “I swear!” he said; but, seeing me hesitate, he added, “What wouldst thou of thy poor, unworthy servant?”

’Twas not so easy to answer him, and I hung my head for a moment; then said: “When I died—in the Norman time, thou rememberest—there was a woman here, and two sunny little ones, blue in the eyes and comely to look upon—— There, shut thy stupid mouth, and look not so astounded! I tell thee they were here—here, in St. Olaf’s Hall—here, at this very high table between me and St. Olaf’s Abbot—three tender flowers, old man, set in the black framing of a hundred of thy corded, wondering brotherhood. Now, tell me—tell me the very simple truth—is there such a woman here, tall and fair, and melancholy gracious? Are there such babes in thy cloisters or cells?”

“It is against the canons of our order.”

“A malison on thee and thy order! Is there, then, no effigy in yon chancel, no tablet, no record of her—I mean of that noble lady and those comely little ones?”

“I know of none, Sir Saint.”

“Think again. She was a franklin, she had wide lands; she reverenced thy Church, and in her grief, being woman, she would turn devout. Surely she built some shrine, or made thee a portico, or blazoned a window to shame rough Fate with the evidence of her gentleness?”

“There is none such in St. Olaf’s. But, now thou speakest of shrines, I do remember one some hours’ ride from here; unroofed and rotten, but, nevertheless, such as you suggest, and in it there is a cenotaph, and a woman laid out straight. She is cracked across the middle and mossy, and there be two small kneeling figures by her head, but I never looked nicely to determine whether they were blessed cherubin or but common children. The shepherds who keep their flocks there and shelter from the showers under the crumbling walls call the place Voewood.”

“Enough, priest,” I said, as I paced hither and thither across the hall in gloomy grief, and then taking my hasty resolution I turned to him sternly—“Make what capital thou list of to-night’s adventure, but remember the next time thou seest a saint may Heaven pity thee if thou art not in better sort—turn thy face to the wall!”

The frightened Abbot obeyed; I shed in a white heap upon the floor my saintly vestments, my miter and crook on top, and then, stepping lightly down the hall, mounted upon a bench, unfastened and threw open a lattice, and, placing my foot upon the sill, sprang out into the night and open world again!

I walked and ran until the day came, southward constantly, now and again asking my way of an astonished hind, but for the most part guided by some strange instinct, and before the following noon I was at my old Saxon homestead.

But could it be Voewood? Not a vestige of a house anywhere in that wide grassy glade where Voewood stood, not a sign of life, not a sound to break the stillness! Near by there ran a little brook, and against it, just as the monk had said, were the four gray walls of a lonely roofless shrine. Over the shrine, on the very spot where Voewood stood—alas! alas!—was a long, grassy knoll, crowned with hawthorns and little flowers shining in the sunlight. I went into the ruined chapel, and there, stained and lichened and broken, in the thorny embrace of the brambles, lay the marble figure of my sweet Saxon wife, and by the pillow—green-velveted with the tapestry of nature—knelt her little ones on either side. I dropped upon my knee and buried my face in her crumbling bosom and wept. What mattered the eclipse while I slept of all those kingly planets that had shone in the English firmament compared to the setting of this one white star of mine? I rushed outside to the mound that hid the forgotten foundations of my home, and, as the passion swept up and engulfed my heart, I buried my head in my arms and hurled myself upon the ground and cursed that tender green moss that should have been so hard—cursed that golden English sunlight that suited so ill with my sorrows—and cursed again and again in my bitterness those lying blossoms overhead that showered down their petals on me, saying it was spring, when it was the blackest winter of desolation, the night-time of my disappointment.