CHAPTER X

I took lodgings that evening with some rough soldiers who kept guard over the town gate, and slept as soundly by their watch-fire as though my country clothes were purple, and a stony bench in an angle of the walls were a princely couch. But when the morning came I determined to better my condition.

With this object in view one of the smallest of my rings was selected, and, with this conveniently hidden, I went down into the town to search for a jeweler’s. A strange town indeed it struck me as being. Narrow and many were the streets, and paved with stones; timber and plaster jutting out overhead so as to lessen the fair, free sky to a narrow strip, and greatly to compress my country spirit. At every lattice window, so amply provided with glass as I had never known before, they were hanging out linen at that early hour to air; and the ’prentice lads came yawning and stretching to their masters’ shutter booths, and every now and then down the quaint streets of that curious city which had sprung—peopled with a new race—from the earth during the long night of my sleep, there rumbled a country tumbril loaded with rustic things, whereat the women came out to chaffer and buy of the smocked cartsmen who spoke the glib English so novel to my ear and laughed and gossiped with them. The early ware I noticed in his cart was still damp and sparkling with the morning dew, so close upon the dawn had he come in, and there in the town where the deep street shadows still lay undisturbed, now and then a Jew, still ashamed, it seemed, to meet any of those sleepy Christian eyes, would steal by to an early bargain, wrapped to his chin in his gabardine—I knew that garment a thousand years ago—and fearfully slinking, in that intolerant time, from house to house and shadow to shadow.

Now and then as I sauntered along in a city of novelties, a couple of revelers in extraordinary various clothes, their toes longer than their sleeves, their velvet caps quaintly peaked, and slashed doublets showing gay vests below, came reeling and singing up the back ways, making the half-waked dogs dozing in the gutters snarl and snap at them, and disturbing the morning meal of the crows rooting in the litter-heaps.

As the sun came up, and the fresh, white light of that fair Plantagenet morning crept down the faces of the eastward walls, the city woke to its daily business. A page came tripping over the cobbles with a message in his belt, the good wives were astir in the houses, and the ’prentices fell to work manfully on booth and bars as merchant and mendicant, early gallant and basketed maid, began the day in earnest.

All these things I saw from under the broad rim of my rustic hat—my ragged, sorrel-green cloak thrown over my shoulder and across my face, and, so disguised, silent, observant—now recognizing something of that yesterday that was so long ago, and anon sad and dubious, I went on until I found what I sought for, and came into a smooth, broad street, where the jewelers had their stalls. I chose one of those who seemed in a fair way of business, and entered.

“Are you the master here?” I asked of a gray-bearded merchant who was searching for the spectacles he had put away overnight.

“My neighbors say so,” he answered gruffly.

“Then I would trade with you.”

Whereon—having found and adjusted his great hornglasses—he eyed me superciliously from head to foot; then said, in a tone of derision:

“As you wish, friend countryman. But will you trade in pearl and sapphire, or diamond pins and brooches, perhaps—or is it only for broken victuals of my last night’s supper?”

“Keep thy victuals for thy lean and hungry lads! I will trade with you in pearl and sapphire.” And thereon, from under my moldy rags, I brought a lordly ring that danced and sparkled in the clear sunlight stealing through the mullioned windows of his booth, and threw quivering rainbow hues upon the white walls of the little den, dazzling the blinking, delighted old man in front of me. “How much for that?” I asked, throwing it down in front of him.

It was a better gem than he had seen for many a day, and, having turned it over loving and wistful, he whispered to me (for he thought I had surely stolen it) one-sixteenth of its value! Thereon I laughed at him, and threw down my cap, and took the ring, and gave him such a lecture on gems and jewels—all out of my old Phrygian merchant knowledge—so praised and belauded the shine and water of each single shining point in that golden circlet, that presently I had sold it to him for near its value!

Then I bought a leather wallet and put the money in, and traded again lower down the street with another ring. And then again at good prices—for competition was close among these goldsmiths, and none liked me to sell the beautiful things I showed them one by one to their rivals—I sold two more.

“Surely! surely! good youth,” questioned one merchant to me, “these trinkets were made for some master Abbot’s thumb, or some blessed saint.”

“And surely again, my friend,” I answered, “you have just seen them drawn from a layman’s finger.”

“Well, well,” he said, “I will give you your price,” and then, as he turned away to pack them, he muttered to himself, “A stout cudgel seems a good profession nowadays! If it were not through fear yon Flemish rascal over the road might take the gem, I at least would never deal with such an obvious footpad.”

By this time I was rich, and my wallet purse hung low and heavy at my girdle, so away I went to where some tailors lived, and accosted the best of them. Here the cross-legged sewers who sat on the sill among shreds of hundred-colored stuffs and the bent, white-fingered embroiderers stopped their work and gaped to hear the ragged, wayworn loafer, whose broad shadow darkened their doorway, ask for silks and satins, yepres and velvet. One youthful churl, under the master’s eyes, unbonneted, and in mock civility asked me whether I would have my surtout of crimson or silver—whether my jupons should be strung with seedling pearls, or just plain sewn with golden thread and lace. He said, that harmless scoffer, he knew a fine pattern a noble lord had lately worn, of minever and silver, which would very neatly suit me—but I, disdainful, not putting my hand to my loaded pouch as another might have done, only let the ragged homespun fall from across my face, and, taking the cap from my raven hair and grim, weather-beaten face, turned upon them.

The laughter died away in that little den as I did so, the embroiderer’s needle stuck halfway through its golden fabric, the workers stared upon me open-mouthed. The cutter’s shears shut with a snap upon the rustling webs, and then forgot to open, while ’prentice lads stood, all with yardwands in their hand, most strangely spellbound by my presence. The conquest was complete without a word, and no one moved, until presently down shuffled the master tailor from his dusky corner, and, waving back his foolish boys, bowed low with sudden reverence as he asked with many epithets of respect in how he might serve me.

“Thanks,” I said, “my friend. What I need is only this—that you should express upon me some of these tardy but courteous commendations. Translate me from these rags to the livery of gentility. Express in good stuffs upon me some of that ‘nobility’ your quick perception has now discovered—in brief, suit me at once as a not too fantastic knight of your time is clad; and have no doubt about my paying.” Whereon I quickened his willingness by a sight of my broad pieces.

Well, they had just such vests and tunics and hose as I needed, and these, according to the fashion, being laced behind and drawn in at the middle by a loose sword-belt, fitted me without special making. My vest was of the finest doeskin, scalloped round the edge, bound with golden tissue, and worked all up the front with the same in leaves and flowers. My hose were as green as rushes, and my shoes pointed and upturned halfway to my knees. On my shoulders hung a loose cloak of green velvet of the same hue as my hose, lined and puffed with the finest grass-green satin that ever came in merchant bales from over seas. Over my right arm it was held by a gold-and-emerald brooch—a “morse” that worthy clothier termed it—bigger than my palm, and this tunic hung to my small-laced middle. My maunch-sleeves were lined by ermine, and hung to my ankles a yard and more in length. On my head, my cap, again, was all of ermine and velvet, bound with strings of seed-pearls. That same kindly hosier got me a pretty playtime dagger of gold and sapphire for my hip, and green-satin gloves, sewn thick upon the back with golden threads. This, he said, was a fair and knightly vestment, such as became a goodly soldier when he did not wear his harness, but with naught about it of the courtly sumptuousness which so hard and warlike-seeming a lord as I no doubt despised.

From hence I went by many a cobble pavement to where the noisy sound of hammers and anvils filled the narrow streets. And mighty busy I discovered the armor-smiths. There was such a riveting and hammering, such a fitting and filing and brazing going on, that it seemed as though every man in the town were about to don steel and leather. There were long-legged pages in garb of rainbow hue hurrying about with orders to the armorers or carrying home their masters’ finished helms or warlike gear; there were squires and men-at-arms idly watching at the forge doors the pulsing hammers weld rivets and chains; and ever and anon a man-at-arms would come pushing through these groups with sheaves of broken arrows to be ground, or an armful of pikes to be rehandled, casting them down upon the cumbered floor; or perhaps it was a squire came along the way leading over the cobbles a stately war-horse to the shoeing.

In truth, it was a sight to please a soldier’s eyes, and right pleasant was it to me to hear the proud neighing of the chargers, the laughing and the talk, the busy whirr of grindstone on sword and axes, the clangor of the hammers as the hot white spearheads went to the noisy anvil, while forges beat in unison to the singing of the smiths! Ah! and I walked slowly down those streets, wondering and watching with vast pleasure in the busy scene, though every now and then it came over me how solitary I was—I, the one impassive in this turmoil, to whom the very stake they prepared to fight for was unknown!

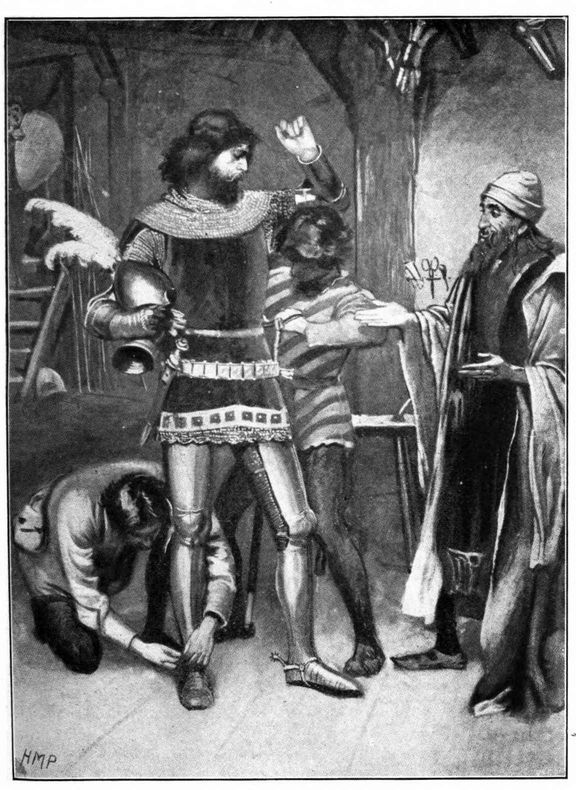

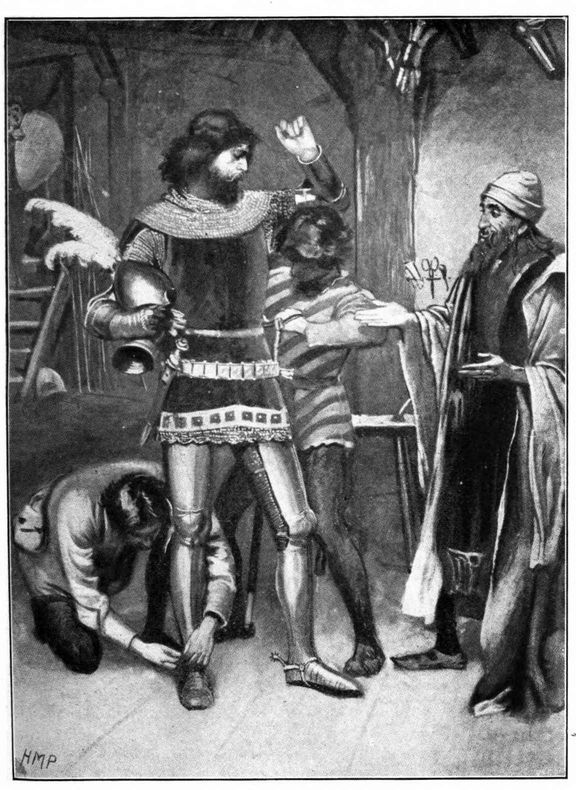

A little way off were the booths where stores of Milan armor were for sale. To them I went, and was shown piles and stacks of harness such as never man saw before, all of steel and golden inlay, covering every point of a warrior, and so rich and cumbersome that it was only with great hesitation I submitted my free Phrygian limbs to such a steel casementing. But I was a gentleman now, whereof to witness came my gorgeous apparel, backing the grim authority of my face, and the bargaining was easy enough. Skogula and Mista! but those swart, olive-skinned, hook-nosed Jewish apprentices screwed me up and braced me down into that suit of Milan steel until I could scarcely breathe—their black-eyed master all the time belauding the sit and comfort of it.

“Gads! Sir,” quoth he, “many’s a hauberk I have seen laced on knightly shoulders, but by the mail from the back of the Gittite, who fell in Shochoh, I never saw a coat of links sit closer or truer than that!” and then again, “There’s a gorget for you, Sir! Why, if Ahab had but possessed such a one, as I am a miserable poor merchant and your Valor’s humble servant, even the blessed arrows of Israel would have glanced off harmlessly from his ungodly body!” And the cunning, sanctimonious old Jew went fawning and smiling round while his helpers pent me up in my glittering hide until I was steel-and-gold inlay from head to heel.

“By Abraham! noble Sir, those greaves become your legs!—Pull them in a little more at the ankles, Isaac!—And here’s a tabard, Sir, of crimson velvet and emblazoned borderings a prince might gladly wear!”

“By Abraham! noble Sir, those greaves become your legs!”

Then they put a helm upon me with a visor and beaver, through which I frowned, as ill at ease as a young goshawk with his first hood, and girded me with a broad belt chosen from many, and a good English broadsword, the dagger “misericordia” at my other hip, and knightly spurs (they gave me that rank without question) upon my heels, so that I was completely armed at last, after the fantastic style of the time, and fit to take my place again in the red ranks of my old profession.

I will not weary you with many details of the process whereby I adapted myself to the times. From that armorer’s shop I went—leaving my mail to be a little altered—to a hostelry in the center square of the town, and there I fed and rested. There, too, I chose a long-legged squire from among those who hung about every street corner, and he turned out a most accomplished knave. I never knew a villain who could lie so sweetly in his master’s service as that particolored, curly-headed henchman. He fetched my armor back the next day, cheating the armorer at one end of the errand and me at the other. He got me a charger—filling the gray-stoned yard with capering palfreys that I might make my choice—and over the price of my selection he cozened the dealers and hoodwinked me. He was the most accomplished youth in his station that ever thrust a vagrom leg into green-and-canary tights, or put a cock’s feather into a borrowed cap. He would sit among the wallflowers on the inn-yard wall and pipe French ditties till every lattice window round had its idle sewing-maid. He would swear, out in the market-place, when he lost at dice or skittles, until the bronzed troopers looking on blushed under their tawny hides at his supreme expurlatives. There was not such a lad within the town walls for strut, for brag, or bully, yet when he came in to render the service due to me he ministered like a soft, white-fingered damsel. He combed my long black hair, anointing and washing it with wondrous scents, whereof he sold me phials at usurious interest; he whispered into my sullen, unnoticing ear a constant stream of limpid, sparkling scandal; he cleaned my armor till it shone like a brook in May time, and stole my golden lace and a dozen of the sterling links from my dagger chain. He knew the wittiest, most delicately licentious songs that ever were writ by a minstrel, and he could cook such dishes as might have made a dying anchorite sit up and feast.

Strange, incomprehensible! that wayward youth went forth one day on his own affairs, and met in the yard two sturdy loafers who spoke of me, and calling me penniless, unknown, infamous—and French, perhaps—for they doubted I was good English—whereon that gallant youth of mine fell on them and fought them—there right under my window—and beat them both, and flogged their dusty jackets all across the market-place to the tune of their bellowings, and all this for his master’s honor! Then, having done so much, he proceeded with his private errand, which was to change, for his own advantage at a mean Fleming’s shop, those pure golden spurs of mine, secreted in his bosom, into a pair of common brass ones.

For five days I had lain in that town in magnificent idleness, and had spent nearly all my rings and money, when, one day, as I sat moody and alone by the porch of the inn drinking in the sun, my idle valor rusting for service, and looking over the market square with its weather-worn central fountain, its cobblestones mortared together with green moss and quaint surroundings, there came cantering in and over to my rest-house three goodly knights in complete armor with squires behind them—their pennons fluttering in the wind, tall white feathers streaming from their helms, and their swords and maces rattling at the saddle bows to the merriest of tunes. They pulled up by the open lattice, and, throwing their broad bridles to the ready squires, came clattering up, dusty and thirsty, past where I lay, my inglorious silken legs outstretched upon the window bench, and the sunlight all ashine upon the gorgeous raiment that irked me so.

They were as jolly fellows as one could wish to see, and they tossed up their beavers and called for wine and poured it down their throats with a pleasure pleasant enough to watch. Then—for they could not unlace themselves—in came their lads and fell to upon them and unscrewed and lifted off the great helms, and piece by piece all the glittering armor, and piling it on the benches—the knights the while sighing with relief as each plate and buckle was relaxed—and so they got them at last down to their quilted vests, and then the gallants sat to table and fell to laughing and talking until their dinner came.

From what I gathered, they were on their way to war, and war upon that fair, fertile country yonder over the narrow seas. Jove! how they did revile the Frenchman and drain their beakers to a merry meeting with him, until ever as they chattered the feeling grew within me that here was the chance I was waiting for—I would join them—and, since it was the will of the Incomprehensible, draw my sword once more in the cause of this fair, many-mastered island.

Nor was there long to wait for an excuse. They began talking of King Edward’s forces presently, and how that every man who could spin a sword or sit a war-horse was needed for the coming onset, and how more especially leaders were wanting for the host gathering, so they said, away by the coast. Whereon at once I arose and went over, sitting down at their table, and told them that I had some knowledge of war, and though just then I lacked a quarrel I would willingly espouse their cause if they would put me in the way of it.

In my interest and sympathy I had forgot they had not known I was so close, and now the effect which my sudden appearance always had on strangers made them all stare at me as though I were a being of another world—as, indeed, I was—of many other worlds. And yet the comely, stalwart, raven-tressed, silk-swathed fellow who sat there before them at the white-scrubbed board, marking their fearful wonder with regretful indifference, was solid and real, and presently the eldest of them swallowed his surprise and spoke out courteously for all, saying they would be glad enough to help my wishes, and then—warming with good fellowship as the first effect of my entry wore off—he added they were that afternoon bound for the rendezvous (as he termed it) at a near castle; “and if I could wear harness as fitly as I could wear silk, and had a squire and a horse,” they would willingly take me along with them. So it was settled, and in a great bumper they drank to me and I to them, and thus informally was I admitted into the ranks of English chivalry.

We ate and drank and laughed for an hour or two, and then settled with our host and got into our armor. This to them was customary enough, nor was it now so difficult a thing to me, for I had donned and doffed my gorgeous steel casings, by way of practice, so often in seclusion that, when it came to the actual test, assisted with the nimble fingers of that varlet of mine, I was in panoply from head to heel, helmeted and spurred, before the best of them. Ah! and I was not so old yet but that I could delight in what, after all, was a noble vestment! And as I looked round upon my knightly comrades draining the last drops of their flagons while their squires braced down their shining plates, and girt their steel hips with noble brands, the while I knew in my heart that if they were strong and stalwart I was stronger and more stalwart—that if they carried proud hearts and faces shining there, under their nodding plumes, of gentle birth and handsome soldierliness—no less did I: knowing all this, I say, and feeling peer to these comely peers, I had a flush of pride and contentment again in my strangely varied lot. Then the grooms brought round our gay-ribboned horses to the cobbles in front, where, mounting, we presently set out, as goodly a four as ever went clanking down a sunny market-place, while the maids waved white handkerchiefs from the overhanging lattices and townsmen and ’prentices uncapped them to our dancing pennons.

We rode some half-score miles through a fertile country toward the west, now cantering over green undulations, and anon picking a way through woodland coppices, where the checkered light played daintily upon our polished furniture, and the spear-points rustling ever and anon against the green boughs overhead.

“What of this good knight to whose keep we are going?” asked one of my companions presently. “He is reputed rich, and, what is convenient in these penurious times, blessed only with daughters.”

“Why!” responded the fellow at his elbow, who set no small store by a head of curly chestnut hair and a handsome face below it, “if that is so, in truth I am not at all sure but that I will respectfully bespeak one of those fair maids. I am half convinced I was not born to die on some scoundrel Frenchman’s rusty toasting-iron. ’Tis a cursed perilous expedition this of ours, and I never thought so highly of the advantages of a peaceful and Christian life as I have this last day or two. Now, which of these admirable maids dost thou think most accessible, good Delafosse?” he asked, turning to the horseman who acted as our guide by right of previous knowledge here.

“Well,” quoth that youth, after a moment’s hesitation, “I must frankly tell you, Ralph, that I doubt if there are any two maids within a score of miles of us who have been tried so often by such as you and proved more intractable. The knight, their father, is a rough old fellow, as rich as though he were an abbot, hale and frank with every one. You may come or go about his halls, and (for they have no mother) lay what siege you like to his girls, nor will he say a word. So far so well, and many a pretty gallant asks no better opportunity. But, because you begin thus propitious, it does not follow either fair citadel is yours! No! these virgin walls have stood unmoved a hundred assaults, and as much escalading as only a country swarming with poor desperate youths can any way explain.”

“St. Denis!” exclaimed the other, “all this but fans the spark of my desire.”

“Oh, desire by all means. If wishes would bring down well-lined maidenhoods, those were a mighty scarce commodity. But, soberly, does thy comprehensive valor intend to siege both these heiresses at once, or will one of them suffice?”

“One, gentle Delafosse, and, when my exulting pennon flutters triumphant from that captured turret, I will in gratitude help thee to mount the other. Difference them, beguile this all too tedious way with an account of their peculiar graces. Which maid dost thou think I might the most aptly sue?”

“Well, you may try, of course, but remember I hold out no hope, neither of the elder nor the younger. That one, the first, is as magnificent a shrew as ever laughed an honest lover to scorn. She is as black and comely as any daughter of Zion. ’Tis to her near every Knight yields at first glance; but—gads!—it does them little good! She has a heart like the nether millstone; and, as for pride, she is prouder than Lucifer! I know not what game it may be this swart Circe sees upon the skyline—some say ’tis even for that bold boy the young Prince himself, now gone with his father to France, she waits; and some others say she will look no lower than a Duke backed by the wealth of the grand Soldan himself. But whoever it be, he has not yet come.”

“By the bones of St. Thomas à Becket,” the young Knight laughed, “I have a mind that that Knight and I may cross the drawbridge together! Canst tell me, out of good comradeship, any weak place in this damsel’s harness?”

“There is none I know of. She is proof at every point. Indeed, I am nigh reluctant to let one like you, whose heart has ripened in the sun of experience so much faster than his head, engage upon such a dangerous venture. They say one gallant was so stung by the calm scorn with which she mocked his offer that he went home and hung himself to a cellar beam; and another, blind in desperate love, leaped from her father’s walls, and fell in the courtyard, a horrid, shapeless mass! Young De Vipon, as you know, stabbed himself at her feet, and ’tis told the maid’s wrath was all because his spurting heart’s-blood soiled her wimple a day before it was due to go to wash! How thrives thy inclination?”

“Oh! well enough: ’twould take more than this to spoil my appetite! But, nevertheless, let us hear something of the other sister. This elder is obviously a proud minx, who has set her heart on lordly game, and will not marry because her suitors seem too mean. How is it with the other girl?”

“Why,” said Delafosse, “it is even more hopeless with her. She will not marry, for the cold sufficient reason that her suitors be all men!”

“A most abominable offense.”

“Ah! so she thinks it. Such a tender, shy and modest maid there is not in the boast of the county. While the elder will hear you out, arms crossed on pulseless bosom, cold, disdainful eyes fixed with haughty stare to yours, the other will not stop to listen—no, not so much as to the first inkling of your passion! Breathe so little as half a sigh, or tint your speech with a rosy glint of dawning love, and she is away, lighter than thistledown on the upland breeze. I know of but two men—loose, worldly fellows both of them—who cornered her, and they came from her presence looking so crestfallen, so abashed at their hopes, so melancholy to think on their gross manliness as it had appeared against the white celibacy of that maid, that even some previous suitors sorrowed for them. This is, I think, the safer venture, but even the least hopeful.”

“Is the maid all fallow like that? Has she no human faults to set against so much sterile virtue?”

“Of her faults I cannot speak, but you must not hold her altogether insipid and shallow. She is less approachable than her sister, and contemns and fears our kind, yet she is straight and tall in person, and, I have heard from a foster-brother of hers, can sit a fiery charger, new from stall, like a groom or horse boy, she is the best shot with a crossbow of any on the castle green, and in the women’s hall as merry a romp, as ready for fun or mischief, as any village girl that ever kept a twilight tryst on a Saturday evening.”

“Gads! a most pleasant description. I will keep tryst with this one for a certainty, not only Saturdays, but six other days out of the week. The black jade may wait for her princeling for a hundred years as far as I am concerned. How far is it to the castle?—I am hot impatience itself!”

“Nor need your patience cool! Look!” said Delafosse, and as he spoke we turned a bend in the woodland road, and there, a mile before us, flashing back the level sun from towers and walls that seemed of burnished copper, was the noble pile we sought.

Certes! when we came up to it, it was a fine place indeed, cunningly built with fosses round about, long barbican walls within them, turreted and towered, and below these again were other walls so shrewd designed for defense as to move any soldier heart with wonder and delight. But if the walls did pleasure me, the great keep within, towering high into the sky with endless buttresses, and towers, and casements, grim, massive, and stately, rearing its proud circumference, embattled and serrated far beyond the reach of rude assault or desperate onset, filled me with pride and awe. I scarce could take my eyes from those red walls shining so molten in the setting sun, yet round about the country lay very fair to look at. All beyond that noble pile the land dropped away—on two sides by sheer cliffs to the shining river underneath—and on the others in gentle, grassy undulations, dotted with great trees, whereunder lay, encamped by tent and watchfire, the rear of King Edward’s army, and then on again into the pleasant distance that lay stretched away in hill and valley toward the yellow west.

All over that wide campaign were scattered the villages of serfs and vassals who grew corn for the lordly owner in peace-time, and followed his banner in battle. And in that knightly stronghold up above there were, I found when I came to know it better, many kinsmen and women who sheltered under my Lord’s liberality. Dowagers dwelt in the wings, and young squires of good name—a jolly, noisy, unruly crew—harbored down in the great vaulted chambers by the sally-port. There were kinsmen of the left-hand degree in the warder’s lodge by the gates, and poor wearers of the same noble escutcheon up among the jackdaws and breezes of the highest battlements. And so generous was the Knight’s bounty, so ample the sweep of his castellated walls and labyrinthine the mazes of the palace keep they encircled, so abundant the income of his tithes and tenure, dues and fees, that all these folk found living and harborage with him; and not only did it not irk that Lord, but only to his steward and hall porter was it known how many guests there were, or when a man came or went, or how many hundred horses stood in the stalls, or how many score of vassals fed in the great kitchen.

On Sundays, after mass, the smooth green in the center of the castle would be thronged with men and maids in all their finery; while the quintains spun merrily under the mock onsets of the young knights, and dame and gallant trode the stony battlements, and down among the wide shadow of the cedar-trees on the slope (’twas a Crusader who brought the saplings from Palestine) vassal and yeoman idled and made love or frolicked with their merry little ones. Over all that gallant show my Lord’s great blazon snapped and flaunted in the wind upon the highest donjon; and in the halls beneath the lords and ladies sat in the deep-seated windows, and laughed and sang and jested in the mullion-tinted sunshine with all the courtly extravagance of their brilliant day.

Ah! by old Isis! at that time the world, it seemed to me, was less complex, and the rules of life were simpler. Kingcraft had found its mold and fashion in the courageous Edward, and the first duty of a noble was then nobility: the Knights swore by their untarnished chivalry, and the vassals by their loyalty. Yes! and it was priestly then to fear God and hell, and every woman was, or would be, lovely! So ran the simple creed of those who sang or taught, while nearly every one believed them.

But you who live in a time when there is no belief but that of Incredulence, when the creative skill and forethought of the great primeval Cause is open to the criticism and cavil of every base human atom it has brought about—you know better—you know how vain their dream was, how foolish their fidelity, how simple their simplicity, how contemptible their courage, and how mean by the side of your love of mediocrity their worship of ideals and heroes! By the bright Theban flames to which my fathers swore! by the grim shadow of Osiris which dogged the track of my old Phœnician bark! I was soon more English than any of them.

But while I thus tell you the thoughts that came of experience, I keep you waiting at the castle-gate. They admitted us by drawbridge and portcullised arch into the center space, and there we dismounted. Then down the steps, to greet guests of such good degree, came the gallant, grizzled old Lord himself in his quilted under-armor vest. We made obeisance, and in a few words the host very courteously welcomed his guests, leading us in state (after we had given our helmets to the pages at the door) into the great hall of his castle, where we found a throng of ladies and gallants in every variety of dress filling those lofty walls with life and color.

In truth, it was a noble hall, the walls bedecked with antlers or spoils of woodcraft, with heads and horns and bows and bills, and tapestry; and the ceiling wonderfully wrought with carved beams as far down that ample corridor as one could see. The floor of oak was dark with wear, yet as smooth and reflective to many-colored petticoats and rainbow-tinted shoes as the Parian marble of some fair Roman villa. And on the other side there were fifty windows deep-set in the wall, with gay stainings on them of parable and escutcheon; while on the benches, fingering ribboned mandolins, whispering gentle murmurs under the tinseled lawn of fair ladies’ kerchiefs, or sauntering to and fro across the great chamber’s ample length, were all these good and gentle folk, bedecked and tasseled and ribboned in a way that made that changing scene a very fairy show of color.

Strange, indeed, was it for me to walk among the glittering throng, all prattling that merry medley they called their native English, and to remember all I could remember, to recall Briton, Roman, Norseman, Norman, Saxon, and to know each and all of those varied peoples were gone—gone forever—gone beyond a hope or chance of finding—and yet, again, to know that each and every one of those nations, whose strong life in turn had given color to my life, was here—here before me, consummated in this people—oh, ’twas strange, and almost past belief! And ever as I went among them in fairer silks and ermines than any, yet underneath that rustling show I laughed to know that I was nothing but the old Phœnician merchant, nothing but Electra’s petted paramour, the strong, unruly Saxon Thane!

And if I thought thus of them, in sooth, they thought no less strangely of me! Ever, as my good host led me here and there from group to group, the laughter died away on cherry lips, and minstrel fingers went all a-wandering down their music strings as one and all broke off in mid pleasure to stare in mute perplexity and wonder at me. From group to group we went, my host at each making me known to many a glittering lord and lady, and to each of those courtly presences I made in return that good Saxon bow, which subsequently I found instable fashion had made exceeding rustic.

Presently in this way we came to a gay knot of men collected round two fair women, the one of them seated in a great velvet chair, holding court as I could guess by word and action over the bright constellations that played about her, the other within the circle, yet not of it, standing a little apart and turned from us as we approached. Alianora, the first of these noble damsels, was the elder daughter of the master of the house, and the second, Isobel, was his younger child. The first of these was a queen of beauty, and from that first moment when I stood in front of her, and came under the cold, proud shine of those black eyes, I loved her! Jove! I felt the hot fire of love leap through my veins on the instant as I bowed me there at her footstool and forgot everything else for the moment, merging all the world against the inaccessible heart of that beautiful girl. Indeed, she was one who might well play the Queen among men. Her hair was black as night, and, after the fashion of the time, worked up to either side of her head into a golden filigree crown, beaded with shining pearls, extraordinary regal. Black were her eyes as any sloe, and her smooth, calm face was wonderful and goddess-like in the perfect outline and color. Never a blush of shame or fear, never a sign of inward feeling, stirred that haughty damsel’s mood. By Venus! I wonder why we loved her so. To whisper gentle things into her ear was but like dropping a stone into some deep well—the ripples on the dark, sullen water were not more cold, silent, intangible than her responsive smile. She was too proud even to frown, that disdainful English peeress, but, instead, at slight or negligence she would turn those unwavering eyes of hers upon the luckless wight and look upon him so that there was not a knight, though of twenty fights, there was not a gallant, though never so experienced in gentle tourney with ladies’ eyes, who durst meet them. To this maid I knelt—and rose in love against all my better instinct—wildly, recklessly enamored of her shining Circean queenliness—ah! so enthralled was I by the black Alianora that my host had to pluck me by the sleeve ere he whispered to me, “Another daughter, sir stranger! Divide your homage,” and he led me to the younger girl.

Now, if the elder sister had won me at first sight, my feelings were still more wonderful to the other. If the elder had the placid sovereignty of the evening star, Isobel was like the planet of the morning. From head to heel she was in white. Upon her forehead her fair brown hair was strained back under a coverchief and wimple as colorless as the hawthorn flowers. This same fair linen, in the newest fashion of demurity, came down her cheeks and under her chin, framing her face in oval, in pretty mockery of the steel coif of an armed knight. Her dress below was of the whitest, softest stuff, with long, hanging sleeves, a wondrous slender middle drawn in by a silk and silver cestus belt made like a warrior’s sword-wear, and a skirt that descended in pretty folds to her feet and lay atwining about them in comely ampleness. She was as supple as a willow wand, and tall and straight, and her face—when in a moment she turned it on me—was wondrous pleasant to look at—the very opposite of her sister’s—all pink and white, and honestly ashine with demure fun and merriment, the which constantly twinkled in her downcast eyes, and kept the pretty corners of her mouth a-twitching with covert, ill-suppressed, unruly smiles. A fair and tender young girl indeed, made for love and gentleness!

Unhappy Isobel!—luckless victim of an accursed fate! Wretched, perverse Phœnician! Ill-omened Alianora! Between us three sprang up two fatal passions. Read on, and you shall see.