CHAPTER XIII

Strange, eventful, and bloody, were the incidents that followed. King Edward, burning for glory, had landed in Normandy a little time before, had knighted on these yellow beaches that gallant boy his son, and with the young Prince and some fourteen thousand English troops, ten thousand wild Welshmen, and six thousand Irish, pillaging and destroying as he went, he had marched straight into the heart of unready France. With that handful of men he had burned all the ships in Hogue, Barfleur, and Cherbourg; he had stormed Montebourg, Carentan, St. Lo, and Valognes, sending a thousand sails laden with booty back to England, and now, day by day, he was pressing southward through his fair rebellious territories, deriding the French King in his own country, and taking tithe and taxes in rough fashion with fire and sword.

Nor had we who came late far to seek for the Sovereign. His whereabouts was well enough to be told by the rolling smoke that drifted heavily to leeward of his marching columns and the broad trail of desolation through the smiling country that marked his stern progress. To travel that sad road was to see naked War stripped of all her excusing pageantry, to see gray desolation and lean sorrow following in the gay train of victory.

Gods! it was a sad path. Here, as we rode along, would lie the still smoldering ashes of a burned village, black and gray in the smiling August sunshine. In such a hamlet, perhaps, across a threshold, his mouth agape and staring eyes fixed on the unmoved heavens, would lie a peasant herdsman, his right hand still grasping the humble weapon wherewith he had sought to protect his home, and the black wound in his breast showing whence his spirit had fled indignant to the dim Place of Explanations.

Neither women nor babes were exempt from that fierce ruin. Once we passed a white and silent mother lying dead in mid-path, and the babe, still clasped in her stiff arms, was ruddy and hungry, and beat with tiny hands to wake her and crowed angry at its failure, and whimpered so pitiful and small, and was so unwotting of the merry game of war and all it meant, that the laughter and talk died away from the lips of those with me, as, one by one, we paced slowly past that melancholy thing.

At another time, I remember, we came to where a little maid of some three tender years was sitting weaving flowers on the black pile of a ruined cottage, that, though her small mind did not grasp it, hid the charred bodies of all her people. She twined those white-and-yellow daisies with fair smooth hands, and was so sunny in the face and trustful-eyed I could not leave her to marauding Irish spears, or the cruel wolfdogs who would come for her at sunset. I turned my impatient charger into the black ruin, and, maugre that little maid’s consent, plucked her from the ashes, and rode with her upon my saddle-bow until we met an honest-seeming peasant woman. To her I gave the waif, with a silver crown for patrimony.

Out in the open the broad stream of war had spread itself. The yellow harvests were trodden under foot, and hedge and fence were broken. The plow stood halfway through the furrow, and the reaper was dead with the sickle in his hand. Here, as we rode, went up to heaven the smoke of coppice and homestead; and there, from the rocks hanging over our path, luckless maids and widowed matrons would hail and spit upon us in their wild grief, cursing us in going, in coming, in peace and in war, while they loaded the frightened echoes with their shrieks and wailings.

Now and then, on grass and roadside, were dark patches of new-dried blood, and by them, maybe, lay country cloaks and caps and weapons. There we knew men had fallen singly, and had long lain wounded or dead, until their friends had taken them to grave or shelter. Out in the open again, where skirmishes had happened and bill and bow or spear had met their like, the dead lay thicker. Gods! how drear those fair French fields did lie in the autumn moonlight, with their scattered dead in twos and threes and knots and clusters! There were some who sprawled upon the ground—still clutching in their dread white fingers the grass and earth torn up in the moment of their agony. And here was he who scowled with dead white eyes on the pale starlight, one hand on his broken hilt and the other fast gripped upon the spear that pinned him to the earth. Near him was a fair boy, dead, with the shriek still seeming upon his livid lips, and the horrid rent in his bosom that had let out his soul looming black in the gloom. Yonder a tall trooper still stared out grimly after the English, and smiled in death with a clothyard shaft buried to the feather in his heart. Some there were of these horrid dead who still lay in grapple as they had fallen—the stalwart Saxon and the bronzed Gaul with iron fingers on each other’s throats, smiling their black hatred into each other’s bloodless white faces. Others, again, lay about whose arms were fixed in air, seeming still to implore with bloody fingers compassion from the placid sky.

One man I saw had died stroking the thin, pain-streaked muzzle of his wounded charger—his friend, mayhap, for years in camp and march. Indeed, among many sorrowful things of that midnight field, the dead and dying horses were not least. It moved me to compassion to hear their pain-fraught whinnies on every hand, and to see them lying so stiff and stark in the bloody hollows their hoofs had scooped through hours of untempered anguish. What could I do for all those many? But before one I stopped, and regarded him with stern compassion many a minute. He was a splendid black horse, of magnificent size and strength; and not even the coat of blood and mud with which his sweating sides were covered could hide, here and there, the care that had but lately groomed and tended him. He lay dying on a great sheet of his own red blood, and as I looked I saw his tasseled mane had been plaited not long before by some soft, skilful fingers, and at every point was a bow of ribbon, such as might well have been taken from a lady’s hair to honor the war-horse of her favorite knight. That great beast was moaning there, in the stillness, thinking himself forgotten, but when I came and stood over him he made a shift to lift his shapely head, and looked at me entreatingly, with black hanging tongue and thirst-fiery eyes, the while his doomed sides heaved and his hot, dry breath came hissing forth upon the quiet air. Well I knew what he asked for, and, turning aside, I found a trooper’s empty helmet, and, filling it from the willowed brook that ran at the bottom of the slope, came back and knelt by that good horse, and took his head upon my knee and let him drink. Jove! how glad he was! Forgot for the moment was the battle and his wounds, forgotten was neglect and the long hours of pain and sorrow! The limpid water went gurgling down his thirsty throat, and every happy gasp he gave spoke of that transient pleasure. And then, as the last bright drops flashed in the moonlight about his velvet nozzle, I laid one hand across his eyes and with the other drew my keen dagger—and, with gentle remorselessness, plunged it to the hilt into his broad neck, and with a single shiver the great war-horse died!

In truth, ’twas a melancholy place. On the midnight wind came the wail of women seeking for their kindred, and the howl and fighting of hungry dogs at ghastly meals, the smell of blood and war—of smoldering huts and black ruins! A stern pastime, this, and it is as well the soldier goes back upon his tracks so seldom!

We passed two days through such sights as I have noted, meeting many a heavy convoy of spoil on its way to the coast, and not a few of our own wounded wending back, luckless and sad, to England; and then on the following evening we came upon the English rear, and were shortly afterward part and parcel of as desperate and glorious an enterprise as any that was ever entered in the red chronicles of war. From the coast right up to the white walls of the fair capital itself, King Edward’s stern orders were to pillage and kill and spoil the country, so that there should be left no sustenance for an enemy behind. I have told you how the cruel Irish mercenaries and the loose soldiers of a baser sort accomplished the command. Our English archers and the light-armed Welsh, who scoured the front, were mild in their methods compared to them. They mayhap disturbed the quiet of some rustic villages, and in thirsty frolics broached the kegs of red vintage in captured inns, robbed hen-roosts, and kissed matrons and set maids screaming, but they, unlike the others, had some touch of ruth within their rugged bosoms. But, as for keeps and castles, we stormed and sacked them as we went, and he alone was rogue and rascal who was last into the breach. Our wild kerns and escaladers rioting in those lordly halls, many a sight of cruel pillage did I see, and many a time watched the red flame bursting from the embrasures and windows of these fair baronial homes, and could not stay it. The Frenchmen in these cases, such of them as were not away with the army we hoped to find, fought brave and stubborn, and we piled their dead bodies up in their own courtyards. Many a comely dame and damsel did I watch wringing white hands above these ghastly heaps, and tearing loose locks of raven hair in piteous appeal to unmoved skies, the while the yellow flames of their comely halls went roaring from floor to floor, and in mockery of their sobs, crashing towers and staircases mingled with the yells of the defenders and the shouting of the pillage.

I fear long ages begin to sap my fiber! There was a time when I would have sat my war-horse in the courtyard and could have watched the red blood streaming down the gutters and listened to the shrieking as cold amid the ruin as any Viking on a hostile conquered strand. But, somehow, with this steel panoply of mine I had put on softer moods; I am degenerate by the pretty theories of what they called their chivalry.

Far be it from me to say the English army was all one pack of bloodhounds. War is ever a rough game, the country was foreign, and the adventure we were on was bold and desperate, therefore these things were done, and chiefly by the unruly regiments, and the scullion Irish who followed in our rear, led by knights of ill-repute, or none. These hung like carrion crows about our flanks and rear, and, after each fight, stole armor from dead warriors bolder hands had slain, and burned, and thieved from high and low, and butchered, like the beasts of prey they were.

On one occasion, I remember, a skirmish befell shortly after we joined the main army, and a French noble, in their charge, was unhorsed upon our front by an English archer. Now, I happened to be the only mounted man just there, and as this silver shining prize staggered to his feet, and went scampering back toward his friends with all his rich sheathing safe upon his back, his gold chains rattling on his iron bosom, and his jeweled belt sparkling as he fled, a savage old English swashbuckler, whose horse was hamstrung—Sir John Enkington they called him—fairly wrung his hands.

“After him, Sir Knight,” screamed that unchivalrous ruffian to me, “after him, in the name of hell! If thou rid’st hard he cannot get away, and run thy spear in under his gorget so as not to spoil his armor—’tis worth, at least, a hundred shillings!”

I never moved a muscle, did not even deign to look down at that cruel churl. Whereon the grizzly old boar-hound clapped his hand upon his dagger and turned on me—ah! by the light of heaven, he did.

“What! not going, you lazy braggart!” he shouted, beside himself with rage—“not going, for such a prize? Beast—scullion—coward!”

“Coward!” Had I lived more than a thousand years in a soldier-saddle to be cowarded by such a hoary whelp of butchery—such a damnable old taint on the honorable trade of arms? I spun my charger round, and with my gloved left hand seized that bully by his ragged beard, and perked him here and there; lifted him fairly off his feet; stretched his corded, knotted throttle till his breath came thick and hard; jerked and pulled and twisted him—then cast the ruffian loose, and, drawing my square iron foot from my burnished stirrup, spurned him here and there, and kicked and pommeled him, and so at last drove him howling down the hill, all forgetful for the moment of prize and pillage!

These lawless soldiers were the disgrace of our camp, they did so rant and roar if all went well and when the battle was fairly won whereto they had not entered, they were so coward and cruel among the prisoners or helpless that we would gladly have been rid of them if we could.

But, after the manner of the time, the war was open to all: behind the flower of English chivalry who rode round the Sovereign’s standard, and the gallant bill and bowmen who wore his livery and took his pay, observing the decencies of war, came hustling and crowding after us a host of rude mercenaries, a horde of ragged adventurers, who knew nothing of honor or chivalry, and had no canons but to plunder, ravish, and destroy.

They made a trade of every villainy just outside the camp, where, with scoundrel hawkers who followed behind us like lean vultures, they dealt in dead men’s goods, bought maids and matrons, and sold armor or plunder under our marshal’s very eyes.

One day, I remember, I and my shadow Flamaucœur were riding home after scouting some miles along the French lines without adventure, when, entering our camp by the pickets farthest removed from the Royal quarter, we saw a crowd of Irish kerns behind the wood where the King had stocked his baggage, all laughing round some common object. Now, these Irish were the most turbulent and dissolute fighters in the army. Such shock-headed, fiery ruffians never before called themselves Christian soldiers. They and the Welsh were forever at feud; but, whereas the Welshmen were brave and submissive to their chiefs, keen in war, tender of honor, fond of wine-cups and minstrels—gallant, free soldiers, indeed, just as I had known their kin a thousand years before; these savage kerns, on the other hand, were remorseless villains, rude and wild in camp, and cutthroat rascals, without compunction, when a fight was over. In ordinary circumstances we should have ridden by these noisy rogues, for they cared not a jot for any one less than the Camp Marshal with a string of billmen behind him, and feuds between knights of King Edward’s table and these shock-haired kerns were unseemly. But on this occasion, over the hustling ring of rough soldiers, as we sat high-perched upon our Flemish chargers, we saw a woman’s form, and craned our necks and turned a little from our course to watch what new devilry they were up to.

There, in the midst of that lawless gang of ruffian soldiers, their bronzed and grinning faces hedging a space in with a leering, compassionless wall, was a fair French girl, all wild and torn with misadventure, her smooth cheeks unwashed and scarred with tears, her black hair wild and tangled on her back, her skirt and bodice rent and muddy, fear and shame and anger flying alternate over the white field of her comely face, while her wistful eyes kept wandering here and there amid that grinning crowd for a look of compunction or a chance of rescue. The poor maid was standing upon an overturned box such as was used to carry cross-bow bolts in, her hands tied hard together in front, her captor by her side, and as we came near unnoticed he put her up for sale.

“By Congal of the Bloody Fingers,” said that cruel kern in answer to the laughing questions of his comrades, interlarding his speech with many fiery and horrid oaths, the which I spare you—“I found this accursed little witch this morning hiding among the rubbish of yonder cottage our boys pulled to pieces in the valley; and, as I could not light on better ware, I dragged her here. But may I roast forever if I will have anything more to do with her. She is a tigress, a little she-devil. I have thrashed and beat and kicked her, but I cannot get the spirit out. Let some other fellow try, and may Heaven wither him if he turns her loose near me again! Now then, what will the best of you give? She is a little travel-stained, perhaps—that comes of our march hither, and our subsequent disagreements—but all right otherwise, and, an some one could cure her of her spitfire nature and make her amenable to reason, she would be an ornament to any tent. Now you, Borghil, for instance—it was you, I think, who split the mother’s skull this morning—give me a bid for the daughter: you are not often bashful in such a case as this.”

“A penny then!” sang out Borghil of the Red Beard; “and, with maids as cheap as they be hereabouts, she’s dear at that,” and, while the laughter and jest went round, those rude islanders bid point by point for the unhappy girl who writhed and crouched before them. What could I do? Well I knew the vows my golden spurs put upon me, and the policy my borrowed knighthood warranted—and yet, she was not of gentle birth—’twas but the fortune of war. If men risked lives in that stern game, why should not maids risk something too? King Edward hated turmoil in the camp, and here on desperate venture, far in a hostile country, my soldier instinct rose against kindling such a blaze as would have burst out among these lawless, hot-tempered kerns, had I but drawn my sword a foot from its scabbard. And, thinking thus, I sat there with bent head scowling behind my visor-bars, and turning my eyes now to my ready hilt that shone so convenient at my thigh, and anon to the tall Normandy maid, so fair, so pitiful, and in such sorry straits.

While I sat thus uncertain, the girl’s price had gone up to fivepence, and, there being no one to give more, she was about to be handed over to an evil-looking fellow with a scar destroying one eye, and dividing his nose with a hideous yellow seam that went across his face from temple to chin. This gross mercenary had almost told the five coins into the blood-smudged hand of the other Irishman, and the bargain was near complete, when, to my surprise, Flamaucœur, who had been watching behind me, pushed his charger boldly to the front, and cried out in that smooth voice of his: “Wait a spell, my friends! I think the maid is worth another coin or two!” and he plunged his hand into the wallet that hung beside his dagger.

This interruption surprised every one, and for a moment there was a hush in the circle. Then he of the one eye, with a very wicked scowl, produced and bid another penny, the which Flamaucœur immediately capped by yet another. Each put down two more, and then the Celt came to the bottom of his store, and, with a monstrous oath, swept back his money, and, commending the maid and Flamaucœur to the bottom-most pit of hell, backed off amid his laughing friends.

Not a whit disconcerted, my peaceful gallant rode up to the grim purveyor of that melancholy chattel, and having paid the silver, with a calm indifference which it shocked me much to see, unwound a few feet of the halter-rope depending from his Fleming’s crupper. The loose end of this the man wound round and tied upon the twisted withies wherewith the maid’s white wrists were fastened.

Such an escape from the difficulty had never occurred to my slower mind, and now, when my lad turned toward the quarter where his tent lay, and, apparently mighty content with himself, stepped his charger out with the unhappy girl trailing along at his side, his lightness greatly pained me. Nor was I pleasured by the laughter and gibes of English squires and knights who met us.

“Hullo! you valorous two,” called out a mounted captain, “whose hen-roosts have you been robbing?” And then another said, “Faith! they’ve been recruiting,” and again, “’Tis a new page they’ve got to buckle them up and smooth their soldier pillows.” All this was hard to bear, and I saw that even Flamaucœur hung his head a little and presently rode along by byways less frequented. At one time he turned to me most innocent-like and said:

“Such a friend as this is just what I have been needing ever since I left the English shore.”

“Indeed!” I answered, sardonically, “I do confess I am more surprised than perhaps I should be. It is as charming a handmaid as any knight could wish. Shall you send one of those long raven tresses home to thy absent lady with thy next budget of sighs and true-love tokens?”

But Flamaucœur shook his head, and said I misunderstood him bitterly. He was going on to say he meant to free the maid “to-morrow or the next day,” when we turned a corner in our martial village street, and pulled up at our own tent doors.

Now, that Breton girl had submitted so far to be dragged along, in a manner of lethargy born of her sick heart and misery, but when we stayed our chargers the very pause aroused her. She drew her poor frightened wits together and glared first at us, and then at our knightly pennons fluttering over the white lintels of our lodgment; then, jumping to some dreadful, sad conclusion, she fired up as fierce and sudden as a trapped tigress when the last outlet is closed upon her. She stamped and raged, and twisted her fair white arms until the rough withies on her wrists cut deep into the tender flesh and the red blood went twining down to her torn and open bodice; she screamed and writhed, and struggled against the glossy side of that gentle and mighty war-horse, who looked back wondering on her and sniffed her flagrant sorrow with wide velvet nostrils—no more moved than a gray crag by the beating of the summer sea—and then she turned on us.

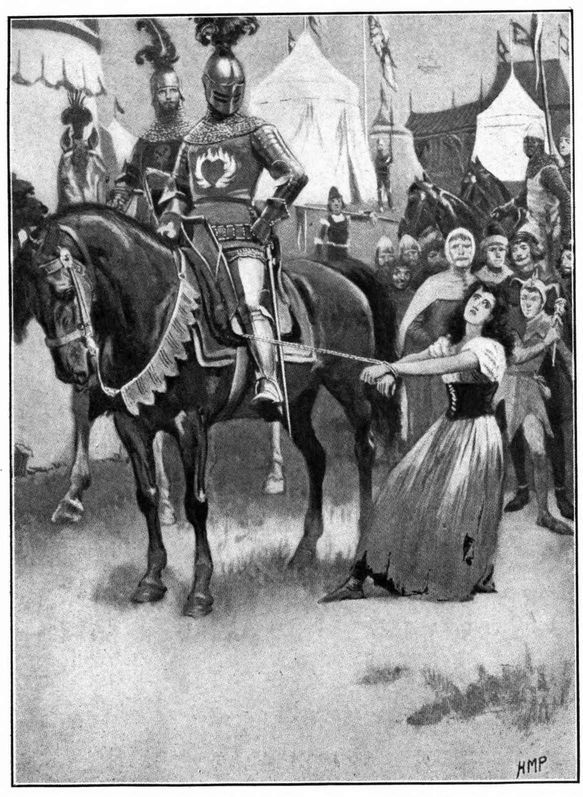

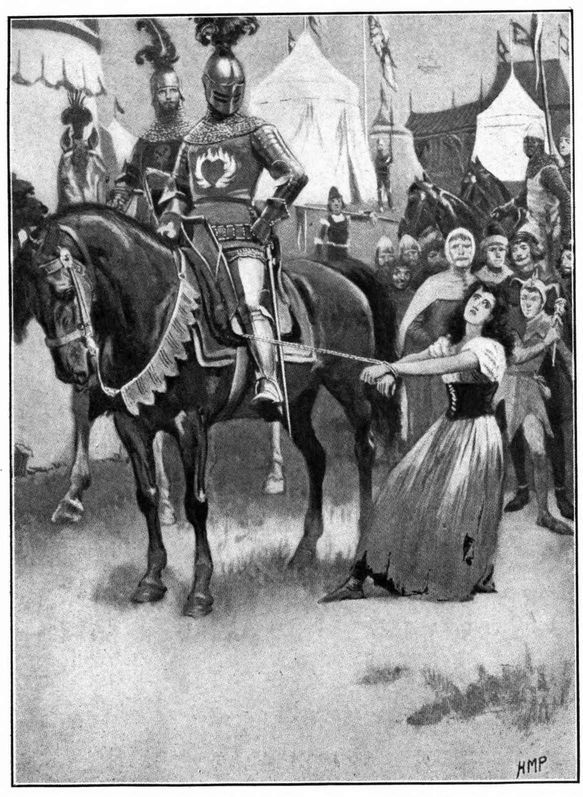

Gads! she swore at us in such mellow Bisque as might have made a hardened trooper envious! Cursed us and our chivalry, called us forsworn knights, stains upon manhood, dogs and vampires!—then dropped upon her knee, and there suppliant, locked her swollen and bloody hands, and, with the hot white tears sparkling in her red and weary eyes, knelt to us, and in the wild, tearful grief of her people, “for the honor of our mothers, and for the sake of the bright distant maid we loved,” begged mercy and freedom.

And all through that storm of wild, sweet grief that callous libertine, Flamaucœur, made no show of freeing her. He sat his prick-eared, wondering charger, stared at the maid, and fingered his dagger-chain as though perplexed and doubtful. The hot torrent of that poor girl’s misery seemed to daze and tie his tongue: he made no sign of commiseration and no movement, until at last I could stand it no longer. Wheeling round my war-horse, so that I could shake my mailed fist in the face of that sapling villain:

“By the light of day!” I burst out, half in wrath and half in amused bewilderment, “this goes too far. Why, Flamaucœur, can you not see this is a maid in a hundred, and one who well deserves to keep that which she asks for? Jove! man, if you must have a handmaiden, why, the country swarms with forlorn ones who will gladly compound with fate by accepting the protection of thy tent. But this one!—come!—let my friendship go in pawn against her, and free the maid. If you must have something more solid—still, set her free, unharmed, and I will give thee a helmetful of pennies—that is to say, on the first time that I own so many.”

But Flamaucœur laughed more scornfully than he often did, and, muttering that we were “all fools together,” turned from me to the wild thing at his side.

“Look here,” he said, “you mad girl. Come into my tent and I will explain everything. You shall be all unharmed, I vow it, and free to leave me if you will not stop—this is all mad folly, though out here I cannot tell you why.”

“I will not trust you,” she screamed, in arms again, straining at those horrid red wrists of hers and glaring on us—“Mother of Christ!” she shouted, turning to a knot of squires and captains who had gathered around us—“for the dear Light of Heaven some of you free my wretched spirit with your maces, here—here—some friendly spear for this friendless bosom—one dagger-thrust to rid me from these cursed tyrants, and I will take the memory of my slayer straight to the seat of mercy and mix it forever with my grateful prayers. Oh, in Christian charity unsheath a weapon!”

“I will not trust you!” she screamed

I saw that slim soldier Flamaucœur groan within his helmet at this, then down he bent. “Mad, mad girl!” I heard him say, and then followed a whisper which was lost between his hollow helmet and his prisoner’s ear. Whatever it was, the effect was instantaneous and wonderful.

“Impossible!” burst out the French girl, starting away as far as the cords would let her, and eyeing her captor with surprise and amazement.

“’Tis truth, I swear it.”

“Oh, impossible!—thou a——”

“Hush, hush,” cried Flamaucœur, putting his hand upon the girl’s mouth, and speaking again to her in his soft low voice, and as he did so her eyes ran over him, the fear and wonder slowly melted away, and then, presently, with a delighted smile at length shining behind her undried tears, she clasped and kissed his hand with a vast show of delight as ungoverned as her grief had been, and when he had freed her and descended from his charger, to our amazement, led rather than followed that knight most willing to his tent, and there let fall the flap behind them.

“Now that,” said the King’s jester, who had come up while this matter was passing—“that is what I call a truly persuasive tongue. I would give half my silver bells to know what magic that gentleman has that will get reason so quickly into an angry woman’s head.”

“If you knew that,” quoth a stern old knight through the steel bars of his morion, “you might live a happy life, although you knew nothing else.”

“Poor De Burgh!” whispered a soldier near me. “He speaks with knowledge, for men say he owns a vixen, and is more honored and feared here by the proud Frenchman than at his own fireside.”

“Perhaps,” suggested another to the laughing group, “he of the burning heart whispered that he had a double Indulgence in his tent. Women will go anywhere and do anything when it is the Church which leads them by the nose.”

“Or, perhaps,” put in another, looking at the last speaker—“perhaps he hinted that if the maid escaped from his hated clutches she would fall into thine, St. Caen, and she chose the lesser evil. It were an argument that would well warrant so sudden a conversion!”

“Well! Well!” quoth the fool, “we will not quarrel over the remembrance of the meat which another dog has carried off. Good-by, fair Sirs, and may God give you all as efficient tongues as Sir Flamaucœur’s when next you are bowered with your distant ladies!” and laughing and jesting among themselves the soldiers strolled away, leaving me to seek my solitary tent in no good frame of mind.