CHAPTER XXIV

After that eventful episode just detailed, life ran smooth and uneventful for a time in the old manor-house. I had had enough to think of for many a day, and was inert and listless somehow. War, that had seemed so bright, had lost its color to me. Honor! and renown! Why, the green grass in the fields were not more fleeting, I began to think; and what use was it striving after conquests which another age undid, or attempting brave adventures whereof a later time recognized neither cause nor purpose? I was in a doleful mood, as you will see, and lay about on Faulkener’s sunny, red-brick terraces for days together, reflecting in this idle fashion, or pressed my suit upon his daughter when other pastimes failed.

Now, this latter was a dangerous sport for one like me, and one whose fair opponent at the game had such a fine untaught instinct for it as Mistress Bess possessed. I began to speak soft things unto that lady’s ear, as you may remember, like many another, for lack of better occupation, and because it seemed so discourteous to be indifferent to the sweet enticement of my friend, and then I took the gentle malady from her, and, growing worse than she had been, how could she do aught but sympathize? And so between us we eked the matter on in ample leisure, until that which was a pretty jest became at last very serious and sober earnest.

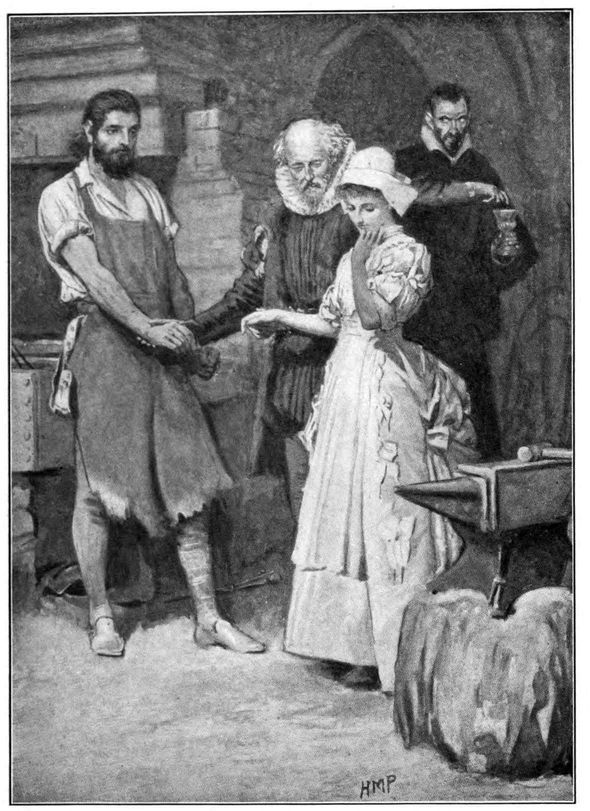

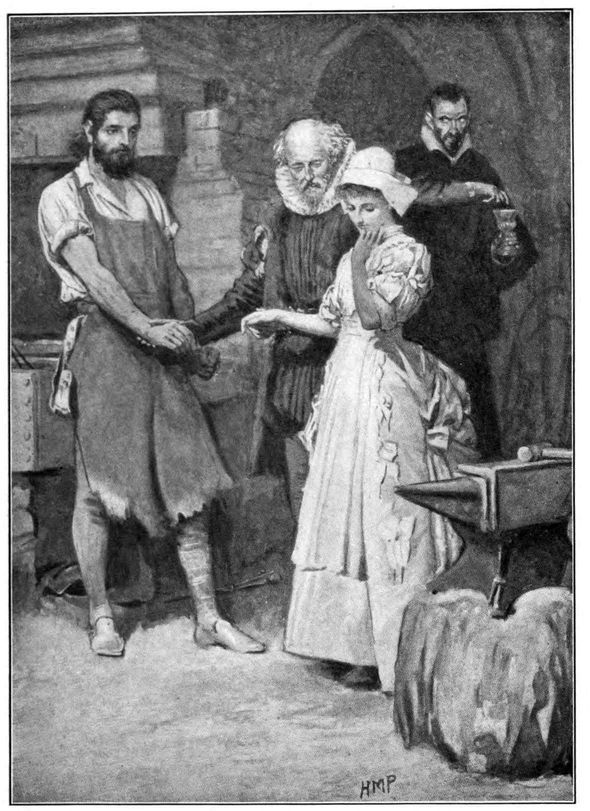

It was a strange wooing. I still worked in the forge, riveting, hammering, and piecing together the fragments of the scholar’s shattered dream, and down the damsel would come at times into the grimy den and sit upon the forge-corner in her dainty country smock, twirling her ribboned points and laughing at me and my toil, as fresh and dainty among all that gloomy black litter round about as a ray of spring sunshine. I was so solitary and glum, how could I fail to be pleasured in that dear presence? And one time I would hammer her a gleaming buckle or wristlet out of a nob of ancient silver, and it was sweet to see that country damsel’s eagerness as, with flushed face and sparkling eyes, she bent over and watched the pretty toy shine and glitter and take form and shape under my cunning hammer. Or then again, perhaps, another day I would tell her, as though it were only hearsay, some wondrous old story of the ancient time, so full of light and color and love as I could fill it, and that dear auditor would drink in every syllable with thirsty ears, and laugh and weep and fear and tremble just as I willed, the while I pointed my periods with my anvil irons, and danced my visionary puppets against the black shadows of that nether hall. Hoth! a good listener is a sweet solace to him whose heart is full! Those narratives did so engross us that often the forge went cold, and bar and rivet slumbered into blackness, while I stalked up and down that dingy cavern peopling it with such glowing forms and fancies as kept that dear untutored damsel spellbound; often the evening fell upon us so, and we had at last to steal shamefacedly across the courtyard to where the warm glow behind the lattices told us supper and the others waited.

There was small difference in these days. I hammered cheerful and I hammered dull, I hammered hopeful and I hammered melancholy, I hammered in tune to the merry prattle of that girl, and I hammered sad and solitary. And ever as I forged and welded by myself you may guess how I thought and speculated—thought of all the love that I had loved, and all the useless strife and ambition, and now hung over my blackening iron as the pain of ancient perplexities and disappointments beset me, and then anon laughed and beat new life into the glowing metal as the light of forgotten joys flashed for a moment on the fitful current of my mind. Ah! and again I forged hot and impetuous on my master’s rods and rivets as the old pulse of battles and onset swelled in my veins—forged and hammered while the stream of such fancies bore me on—until, unwitting, the very molten stuff beneath my hands took form and fashion of my thoughts, and grew up into shining spear-heads and white blades until the fantasy in turn was passed, and I checked my fancies and saw, ashamed, the foolish work my busy hammer had fashioned, and sadly broke the spear-heads and snapped the blades, and came back with a sigh to meaner things.

My mind being thus full of all those wild adventures and wondrous exploits I had seen and shared, when, as I was strolling one idle morning down Faulkener’s dusty museum corridor, and sampling as I went his precious tomes, that thing happened to which you owe this book. I dipped into his missals and vellums as I sauntered from shelf to shelf, and soon I found there was scarcely a page, scarcely a passage within their mothy leathern covers that did not touch me nearly, or set me thinking of something old and wonderful. There was not a page in all that fingered, scholar-marked library, it seemed to me, upon which I could not find something better or nearer to the shining truth to say than they had who wrote those cupboard histories and philosophies; and first I was only sad to see so much inaccurate set down, and then I fell to sighing, as I turned the leaves of quaint treatise and pedantic monkish diary, that they should write who knew so little, and I, who knew so much, should be so dumb. And thus vague fancies began to form within my mind, and, backed by the brooding memories strong within, began to egg me on to write myself! Jove! I had not touched a pen for many hundred years, and yet here was the budding hunger for expression rising strong within me, and I laughed and went over to old Faulkener’s great oak table by the mullioned window, and took up his quill, and turned it here and there, and looked on both ends of it, then presently set it down with a shake of the head as a weapon past my wielding. I felt the texture of his vellums and peered into the depth of his inkpot, as though there were to see therein all those glowing facts and fancies that I yearned to draw therefrom. But it would not do; not even the challenge of those piled tomes, not even the handy means to the end I coveted, could for a time break down my diffidence.

So I fell melancholy again, and wandered down that quaintly stocked museum library, gazing ruefully on each sad remnant of humanity, and thinking how quaint it was that I should come to dust my kinsmen’s skulls and tabulate those grim old heads that had so often wagged in praise of me, then back again to the shelves, and pored and pondered over the many-authored books, until, by hap, my eyes lit upon a passage in an Eastern tale that was so pregnant with experience, so fine, it seemed to my mood, in fancy and philosophy, that it entranced me and fired my zeal to a point naught else had done.

The ancient Arabian narrator is telling how one came, in mid desert, upon a splendid, ruined city—a silent, unpeopled town of voiceless palaces and temples—and wandered on by empty street and fallen greatness until, in the stateliest court of a thousand stately palaces, he found an iron tablet, and on it was written these words:

In the name of God, the Eternal, the Everlasting throughout all ages: in the name of God, who begetteth not, and who is not begotten, and unto whom there is none like: in the name of God, the Mighty and Powerful: in the name of the Living who dieth not. O thou who arrivest at this place, be admonished by the misfortunes and calamities that thou beholdest, and be not deceived by the world and its beauty, and its falsity and calumny, and its fallacy and finery; for it is a flatterer, a cheat, a traitor. Its things are borrowed, and it will take the loan from the borrower; and it is like the confused visions of the sleeper, and the dream of the dreamer. These are the characteristics of the world: confide not therefore in it, nor incline to it; for it will betray him who dependeth upon it, and who in his affairs relieth upon it. Fall not into its snares, nor cling to its skirts. For I possessed four thousand bay horses in a stable; and I married a thousand damsels, all daughters of Kings, high-bosomed virgins, like moons; and I was blessed with a thousand children; and I lived a thousand years, happy in mind and heart; and I amassed riches such as the Kings of the earth were unable to procure, and I imagined that my enjoyments would continue without failure. But I was not aware when there alighted among us the terminator of delights, the separator of companions, the desolator of abodes, the ravager of inhabited mansions, the destroyer of the great and the small, and the infants, and the children, and the mothers. We had resided in this palace in security until the event decreed by the Lord of all creatures, the Lord of the heavens, and the Lord of the earths, befell us, and the thunder of the Manifest Truth assailed us, and there died of us every day two, till a great company of us had perished. So when I saw that destruction had entered our dwellings, and had alighted among us, and drowned us in the sea of deaths, I summoned a writer, and ordered him to write these verses and admonitions and lessons, and caused them to be engraved upon these doors and tablets and tombs. I had an army comprising a thousand thousand bridles, composed of hardy men, with spears, and coats of mail and sharp swords, and strong arms; and I ordered them to clothe themselves with the long coats of mail, and to hang on the keen swords, and to place in rest the terrible lances, and mount the high-blooded horses. Then, when the event appointed by the Lord of all creatures, the Lord of the earth and the heavens, befell us, I said, O companies of troops and soldiers, can ye prevent that which hath befallen me from the Mighty King? But the soldiers and troops were unable to do so, and they said, How shall we contend against Him from whom none hath secluded, the Lord of the door that hath no doorkeeper? So I said, Bring to me the wealth! (And it was contained in a thousand pits, in each of which were a thousand hundredweights of red gold, and in them were varieties of pearls and jewels, and there was the like quantity of white silver, with treasures such as the Kings of the earth were unable to procure.) And they did so; and when they had brought the wealth before me, I said to them, Can ye deliver me by means of all these riches, and purchase for me therewith one day during which I may remain alive? But they could not do so. They resigned themselves to destiny, and I submitted to God with patient endurance of fate and affliction until he took my soul and made me to dwell in my grave. And if thou ask concerning my name, I am Khoosh, the son of Sheddád, the son of ’Ad the Greater.

“Oh, well written!” I cried. “Well written, Khoosh, the son of Sheddád, the son of ’Ad the Greater, well and wisely written, and also I will write, for I have much to tell, and I too may some day be as thou art!”

Thus was the beginning of this book. I got pen and ink and a volume of unwritten leaves forthwith, and carried them away to a lonely chamber in the thickness of a turret wall, a little forgotten cell some six poor feet across, and there solitary I have written, and still write, peopling by the flickering yellow lamp-light that stony niche with all the brilliant memories that I harbor, letting my recollection wander unshackled down the wondrous path that I have come, and step by step, by episodes of pain and pleasure, by wild adventure and strange mischance down, far down, from the ancient times I have brought you until now, when my ink is still wet upon the events of yesterday, and I cease for the moment.

This, then, is all that there is to say, all but one suggestive line. I and yonder fair damsel have plighted troth under the apple-trees out in her orchard! We have broken a ring, and she has one half of it and I have the other. To-morrow will we tell her father, and presently be married. ’Tis a right sweet and winsome maid, and together, hand in hand, we will rehabilitate this ancient pile, and dock that desert garden, and get us friends, and troops of curly-headed children, and lie and bask in the jolly sunshine of contentment—and so go hand in hand forever down the pleasant ways of peaceful dalliance.

Jove!—my pen, and a few poor minutes more from the bottom dregs of life! It is over! all the long combat and turmoil, all the success and disappointment, all the hoping and fearing. That which I thought was a beginning turns out to be but an ending. My hand shakes as I write, my life throbs, and my blood is on fire within me; I am dying, friendless and alone as I have lived, dying in a niche in the wall with my great unfinished diary before me—and, with the grim briefness of my necessity, this is how it has happened.

I had wooed and won Elizabeth Faulkener, and, on the day after she had come down into the forge, as was her wont, sweet and virginal; and I was there at work, and took her into my arms; and, while we dallied thus, there entered on us the ancient scholar and the swart steward. Gods! that villain blanched and scowled to see us so till his swart face was whiter than the furnace ashes.

I took the maiden’s hand, and boldly turning to her father told my love and its accomplishment, whereat she burst from me and threw herself upon his bosom, and, radiant with confusion, such a sweet country pearl as any Prince might well have stooped to raise, she pleaded for us.

Oh! a thousand thousand curses on that black fell shadow standing there behind her! The father, relenting, kissed the fair white forehead of that winsome girl. He bid Emanuel bring at once a loving-cup, and, while that foul traitor reeled away to fetch it, he joined our hands and gave us, in tones of love and gentleness, his blessing.

Then back came the scoundrel Spaniard, his lean, hungry face all drawn and puckered with his wicked passions, and in his hand a silver bowl of wine. O Jove! how cruel it flames within me now! My sweet maid took it, and, rueful for the pain she had given black Emanuel, spoke fair and gentle, saying how we would ever stay his friends and do our best to prosper him. And even I, generous like a soldier, echoed her sweet words, telling that fell knave how, when the game was played and finished, even the worst rivals might meet once more in good comradeship. And so—while the mean Spanish hound, with cruel jaw dropped down and, hands a-twitching at his side, turned from us—his tender mistress lifted the goblet to her lips and drank.

Then came the scoundrel Spaniard, his lean, hungry face all drawn and puckered with his wicked passions

She drank, and because she was no courtly goblet-kissing dame, she drank full and honest, then passed the troth-cup to me—and I laughed and swept aside my Phrygian beard, and happy once more and successful, at the pink of my ambition, pledged those friendly two, pledged even yon black-hearted scoundrel scowling there in the shade, then poured all that sweet, rosy-tasting, love-cup of promise down my thirsty throat.

Gods! what was that at bottom of it? a pale, bitter white dreg. Oh! Jove, what was this? I dipped a finger in and tried it, while a dead hush fell upon us four. It was bitter, bitter as rue, cold, horrible, and biting. My fingers tightened slowly round the goblet stem. I looked at the sweet lady, and in a minute she was swaying to and fro in the pale light like a fair white column, and then her hands were pressed convulsive for a space upon her heart, while her knees trembled and her body shook, and then, all in an instant, she locked her fair fingers at arm’s length above her head, and, with a long, low wail of fear and anguish that shall haunt forever that stony corridor, she staggered and dropped!

Down went the goblet, and I caught her as she fell; and there she lay, heaving a moment in my arms, then looked up and smiled at me—smiled for one happy second her own dear smile of love and sunshine—then shut her eyes, trembling a little, and presently lay still and pale upon my bosom—dead!

Fair, fair Elizabeth Faulkener!

I held her thus a space, and it was so still you could hear the gentle draught of the curling smoke filtering up the chimney, and the merry twitter of the swallows perched far above it. I held her so a space, then kissed her fiercely and tender once upon her smooth forehead, and gave the white girl to her father.

Then turned I to the steward, the bitter passion and the deadly drug surging together like molten lead within my veins. So turned I to him, and our eyes met—and for a moment we glared upon each other so still and grim that you could hear our hearts pulsing like iron hammers, and at every beat a long year of terror and shame seemed to flit across the ashy face of that coward Iberian; he withered and grew old, grew lean and haggard and pinched and bent in those few seconds I stared at him. Then, without taking an eye from his eyes, slowly my hand was outstretched and my sword was lifted from the anvil where I had thrown it. Slowly, slowly I drew the weapon from its sheath and raised it, and slow that villain went back, staring grimly the while, like the dead man that he was, at the point. Then on a sudden he screamed like a rat in a gin, and turned and fled. And I was after him like the November wind after the dead leaves. And round and round the forge we ran, fear and bitter, bitter vengeance winging our heels; and round the anvil with its idle hammer and cold half-welded iron swept that savage race; round by where the pale father was bending over the soft dead form of his sweet country girl; round the ruined chaos of the great broken engine; round by the cobwebbed walls of that gloomy crypt; round by the clattering heaps of iron in a mad, wild frenzy we swept—and then the Spaniard fled to a little oaken wicket in the stony wall leading by many score of winding steps far out into the turrets above.

He tore the wicket open and plunged up that stony staircase, and I was on his heels. Up the clattering stairs we raced—gods, how the fellow leaped and screamed—and so we came in a minute out into the air again, out on to old Andrew Faulkener’s ancient roof, out all among his gargoyles and corbie steps, with the pleasant summer wind wafting the blue smoke of luncheon-time about us, and the courtyard flags far, far down below.

And there I set my teeth, and drew my sinews together, and wiped the cold sweat of death from off my forehead, and stilled the wild, strong tremors that were shaking my iron fabric, and, lost in a reckless lust of vengeance, crouched to the spring that should have ended that villain.

He saw it, and back he went step by step, screaming at every pace, hideous and shrill; back step by step, with no eyes but for me; back until he was, unknowing, at the very verge of the roof; back again another pace—and then, Jove! a reel and a stagger, and he was gone, and, as I rushed forward and looked down, I saw him strike the parapets a hundred feet below and bound into the air, and fall and strike again, and spin like a wheel, and be now feet up and now head, and so, at last, crash, with a dull, heavy thud, a horrid lifeless thing, on the distant stones of that quiet courtyard!

It is over, and I in turn have time to laugh. I have come here, here to my secret den in the thickness of these great walls, staggering slowly here by dim, steep stairs, and rare-trodden landings—here to die; and I have double-locked the oaken door, and shot the bolts and pitched the key out of my one narrow window-slit, and, gently rocking and swaying as the strong poison does its errand, I have thrown down my belt and sword and opened my great volume once again.

Misty the letters swim before me, and the strong pain ebbs and flows within. All the room is hazy and dim, and I grow weak and feeble, and my heavy head sags down upon the leaf I strive to finish. Some other time shall find that leaf, and me a dusty, ancient remnant. Some other hand shall turn these pages than those I meant them for: some other eyes than theirs shall read and wonder, and perhaps regret. And now I droop anon, and then start up, and the pale swinging haze seems taking the shapes of friendliness and beauty. There are no longer limits to this narrow kingdom, and before my footstool sweep in soft procession all the shapes that I have known and loved. Electra comes, a pale, proud shade, sweeping down that violet road, and holding out her ivory palm in queenly friendship; and Numidea trips behind her, and nods and smiles; and there is stalwart Caius, his martial plumes brushing the sky; and earlier Sempronius, brave and gentle; and jolly Tulus; and, two and two, a trooping band of ancient comrades.

Now have I looked up once more and laughed, and here they come trooping again, those smiling shadows, and the fair Thane is with them, her plaited yellow hair gleaming upon her unruffled forehead; and by either hand she leads a rosebud babe, who stretch small palms toward and voiceless cries upon me; and white-bearded Senlac; and, two and two, my Saxon serfs and franklins come gliding in. And there strides gallant Codrington, leading a pale shadow all in white, and Isobel turns a fair pale face upon me as she goes by. Oh! I am dead—dead, I know it, all but the hand which writes and the eyes that see, and I laugh as the last fitful flashes of the pain and life fly through the loosening fabric of my body.... And now, and now a hush has fallen on those silent shades, and their hazy ranks have fallen wide apart, and through them glides ruddy Blodwen—Blodwen, who comes to claim her own—and, approaching, looks into my eyes, and all those stately shadows are waiting, two and two, for us two to head them hence; and she, my princess, my wife, has come near and touched my hand, and at that touch the mantle of life falls from me!

Blodwen! I come, I come!

THE END