CHAPTER V

THE BOATMEN

When it is warm there is no sound sweeter to me than the sound of splashing water. It was such a sound that came to my ears as I awoke from my sleep on a little leaf-covered mound, beneath the boughs of a thicket-surrounded beech tree on a gently sloping and wooded hillside. I knew that near me a brook came hurrying down the slope, and that it was its rejoicing that I heard as it tumbled in little cataracts along its stony bed. It had worn the stone for centuries, and had accomplished much on its way to the deep waters of which it was in search; but of such matter of course I did not think as I opened my eyes and realized what were my surroundings. I knew that I was content and sound and full of vigour, though only half awake as yet, but somehow I was puzzled. Of what had I been dreaming, and which was the real, and which the unreal? I seemed at home where I was, and yet it seemed but an hour ago that there were birds,—birds which were good to eat, about me, and that there were sweet berries, and that I had eaten them, and then had gone to sleep. But there were no birds about me now, and there were no berry bushes. The beech tree was familiar, and so were the singing and laughing of the water. I was in my own place and well. What foolish things are dreams!

There came a long call,—“Co-ee! coo-ee!”—from a distance below me, and the sound was most familiar. It was the call of Droopeye, close friend and companion of mine, though not, it may be, so near to me as Thin Legs the wise one, upon whom I relied concerning many things of which I was in doubt. But I cared much for the merry Droopeye, who made one forget the heavy thoughts which would come at times, and we were often together in our hunting or any other of the journeys made by us, the men of the water caves.

I was glad to hear the summons of Droopeye—he was called so because he had had a hurt in his youth such that one eyelid drooped, and gave him an odd look—since there had come to me strange dreams as I slept there beside the brook which tumbled down the hillside into the lake. I wonder why it is that I have always had strange dreams? Queer and singular they have been, not like those dreamed by my tribesmen, as they have told them to me. They dream of the hunt or the fishing or of the men and women among us; but I do not dream of such things. My dreams are such as I cannot understand; for they are of places and people and ways ever different from what is all about me, of men and women and lands and beasts I have never seen, of countries of hot sands and mighty deserts, or deep, steaming jungles, or cold lands of ice and snow, or of mighty forests where were no men at all, but only fierce, wild creatures upon the ground, and in the treetops other creatures looking somewhat like men indeed, but living in lofty nests, and ever fearful of the beasts below. I do not understand these dreams, and they make me wonder, with almost a little fear. Before the call of Droopeye I had dreamed of a far land of caves and people somewhat like our own, it is true, but with cruder spears and bows and arrows, and with some trouble in the making of fire, which has become to us so easy. And it seemed to me, too, that in my dreams I had myself been in some great peril, but I remembered it only dimly.

So, when I awoke to the call of Droopeye, I answered lustily and leaped to my feet, and met him as he came running up the slope from the shining water. He held in his hand a wonderfully bright shell, which he had found upon the shore, and which he showed to me laughingly.

It is hard to say why I, so different in all my ways, should care at all for the companionship of such a man as Droopeye, who was not the best aid in the hunt, and who could not run as fast or far as I, nor send an arrow from his bow so surely and so strongly. But I liked to have him with me, to hear his merry words, often, it seemed to me, not at all unwise, and to laugh at his shots, when, as he often did, he missed the little standing deer upon which he had crept unseen, or the great bustard which offered so fair a mark. Surely a poor bowman was Droopeye, though a good fisherman, and knowing as to all the roots and fruits and berries which were fit for eating. So I liked to have him with me in the forest or in the hills, despite his uselessness in the hunt, and cared for him as I have seen some great wild beast endure and seem to care for a lesser one about him. Ever ready was Droopeye to build the fire with the hard pointed stick twisted with the bowstring into the dried, punky wood, and he was ready in the skinning and in carrying his burden of whatever might be our spoil to the distant camp.

It was Droopeye who first learned to make sounds upon stretched skins, which drew to him the younger men and the girls, and made them utter odd singing noises, and want to skip about. Very curious was this thing. We had been at work upon the skin of a groundhog, one time, scraping it clean of all flesh, and making it fit for use as some sort of pouch, and when we had done this Droopeye stretched it across the end of a short hollow length of log which chanced to be lying near his hut, that it might dry there flat and firm until he should take it off to knead and stretch into softness, as was the way. It was pinned tightly with strong thorns driven through its edge into the wood, and there it dried, flat and taut and firm. Then, one day, when I was with him, Droopeye remembered the skin he had left out in the sun to dry so, and brought it to the entrance of the hut, where he took a seat beside me, preparing to pull out the thorns, and make the skin soft again by kneading. We were talking, and he forgot for the time about the skin, playing with a short, hard stick he had chanced to pick up as we talked. At last he lifted the short length of log—it was light and thin and very dry—and, in idleness, hit the skin a smart blow with the stick he held. The sound made us both leap to our feet, it was so loud and odd and booming in a queer way. Again and again did Droopeye hit the skin, and each time came the booming sound, and others came running to see what it was.

“I will not take off the skin,” said Droopeye then. “I will keep the sounding thing to play with.”

And this he did; and it came, at last, that he fastened a skin across the other end of the little dried hollow log, and the booming was increased, and a great thing finally came of this, for, in time, a bigger length of hollow log was taken, and chipped and scraped smooth inside and outside, and when other skin was stretched and fastened tightly across the ends, and the thing was beaten, the booming drumming could be heard from afar, and we had a means of summons for all the tribe should any time of peril come.

But the sounding upon the skin was not all that came of this queer discovery of Droopeye. It so pleased him that he tried stretching more skins across hollow things, making still different sounds, and other sound-making things he tried. Finally he stretched a bowstring of sinew above the half of a great dried wild gourd upon which a skin was stretched, and it made a twanging which pleased him much, though the sound was not at all like that of the beating upon the drum.

Then to Droopeye came another fancy, for he was ever different from the rest of the tribe, in thinking of that which might be strange and new. There was a boy so pinched of face that he was called the Rat, and this Rat was so charmed by the noise that Droopeye made with his new things that he was hovering about constantly when the sounds were made. Him Droopeye taught to strum upon the sinew stretched across the gourd, and soon they would make the new and strange noises together and at night—that is, in the early night, when the hunters and others had returned to camp, and had eaten—there would always be a swift clustering around the players, though I cannot tell why this was so. The strumming noise seemed to touch the feet of those who listened, and they moved uneasily, and would often shout when the sounds came swiftly and regularly together in some way I had never heard before. Very odd it was to see them thus swaying together, sometimes clapping their hands as the sounds came, and at last they would caper and circle about, stepping as came the sounds, and all were delighted with it. So came what Droopeye said was the first music, and, whatever it may be, it assuredly was marvellous.

Such a merry man was Droopeye, whose call I answered, and with whom I often went to the huts and caves of our little village by the lake in the hills. He had done a wonderful thing, but nothing so wonderful as that which Thin Legs and I did, and which proved so great a thing for all the tribe.

Never before, so the old men said, had the Cave people been more quiet and prosperous; for we had a good region in which to live, the winters were not so white and hard as they were in the times of which the old men say their fathers’ forefathers told, and there were fewer of the great man-eating wild beasts. Very huge and dangerous were these beasts once, and even at this time it was not good to meet the great bear or the tree leopard, or the wolf pack, or even the huge lone wolf which sometimes crouches by the woodpaths at night, and springs out upon and tears the throat of the unwary. Once such a wolf sprang out upon me; but I throttled him, though my arms were torn, and I was sick and weak for many days. The teeth of the old wolf are very long; but I am strong, and my grip is crushing.

We had not been at war with any other tribe since I was a youth, and we had not been driven away from the camping place by the great floods which sometimes came in the past times, and so we had thriven here, and had done many things. There were the boat and the barb!

Very well do I remember how the first boat came. It was after a great storm, before which I had been hunting with One Ear far up the river which runs to the sea, and to which one now paddles through the lake from which the creek runs to our smaller lake about which were our huts and caves. The water had come in a vast flood, and had caught us in the distant valley, and we had climbed into a tree, that we might not drown, and there we crouched and clung throughout the night. When morning came we could see nothing but the tops of other trees and the great waters. We were weak and hungry. We must leave the tree or die; and, when a log big enough to carry us both came closely by, we dropped down upon it together. We were swept into the deep water, and tossed about in eddies, and tangled and delayed, but not for a very long time. We were going straight toward a little island I knew well, though only its bare crest now showed above the waters.

We stranded against the island’s shore, and crawled up a little way, and rested, lying very still, for there was little life left in us. At last I rose and looked about, and then I shook One Ear by the shoulder, and shouted loudly. There was game upon the little island, game imprisoned by the flood. There were hares, a score of them; and we slew them with our axes, for they could not escape, and fed upon them, for we were famished. Then we slept, and it was night when we awoke. We were hungry still, and ate and slept again until the morning came.

The storm was ended, but not the flood. We could see no land except the little space on which we were, and even that was lessening. What should we do? We ate more of the hare, and sat down upon the sand, and One Ear became sad, and howled as the lone wolf sometimes does. The sound was not good to me, for it made me sorrowful, and I threw my axe at him, but did not hit him. Nevertheless, he ceased his howling.

It was mid-afternoon when I saw coming down the river what seemed to float higher on the water than did the other things. As it neared us, I recognized it as something I had seen before. It was only a log, but it turned up at the ends, and rode high in the water, because it was hollow throughout most of its length, and nearly to its bottom.

Often had I seen that curious log in my hunting far up the river, and well I understood what had made it as it was. The old sycamore which had stood so long beside the river had been blown down, and in falling had struck an uprearing jagged rock, which broke it in two not far from its torn stump. This part of the trunk rolled aside a little way, a log of three men’s length and not straight, but curved upward a little at each end, for the tree had grown crookedly. The log had lain there long, as I had seen it, and become dry and light, and the middle, on its upper side, had become a little rotten and wormy. Then came the great crested woodpecker, the bird which calls so loudly, who hammered and bored away in search of grubs until he had left there a furrow of dry dust and chips. The big pine tree which stood near the sycamore was smitten by the lightning, and sparks from its flaming top had fallen on the dust on the log left by the woodpecker, and so the fire upon the log burned, eating its way deeply downward and extending either way. It had almost reached the ends, and was nearly through the sides and bottom of the log, when a torrent of rain fell, and there was no more fire, but still left of the log a big charred and hollow thing, at the look of which I had often wondered. But I had thought it worthless. Of what use was a charred and hollow log?

It floated so high that, as it grounded on the beach of the little island, it came easily within reach of our hands, and we pulled it ashore. We chattered foolishly over it, and then, all at once, to each of us, came the thought that the thing might carry us more easily than the heavier log which had brought us to where we were. We must leave the island or starve. There were no more hares. We put the log in the water again, and I held it by an end while One Ear waded out and got astride it. Then a new thought came to him, and he lifted his legs and dropped squattingly into the great hollow the fire had made, and looked up at me, and cackled excitedly. The log floated, and yet he was away from the water! I clambered in beside him with a shout, the current caught us and carried us away, and then we yelled together in our exultation. We were floating, warm and dry, and resting. We would have suffered, clinging desperately to the log, with our bodies in the chill water, and, it might be, fallen off and drowned. It was wonderful! Never had men floated thus before, and we were great men indeed! Swiftly we were carried toward the promontory afar down where were the caves where we and our people dwelt. Close in, just at nightfall, the current swayed us, and we leaped out as we reached the shallows, and dragged our prize ashore, while the clan gathered about us, all chattering and wondering. We had what we came to call a Boat!

We ate much and slept soundly, after this our great peril and great discovery. In the morning followed another gathering of the Cave people about the strange thing which could carry men safely upon the water; and he who could draw pictures of wild creatures on the rocks, and who could chip spear-heads most wisely of us all, was the one who looked upon the fire-hollowed log longest and most earnestly, though he at first was silent. Then finally he came to me. A boat seemed to be a good thing. Why not have another boat? What fire had done, fire could do!

Not far from the caves, and close by the shore of the currentless lagoon which reached in from the river, lay the trunk of a large fallen tree. Our stone axes were good, so Thin Legs said, but might not suffice to make a boat like that brought by One Ear and me; but surely we could in time hack off a log, and then make the fire which warmed us and cooked our food do the rest. So we fell to work eagerly, all the strong men of the clan coming to aid in turn. It was long work and wearing, and there were tired arms and blistered hands, but within two days the log was hacked away from the trunk of the fallen big tree, and then Thin Legs alone took leadership, and fire was brought.

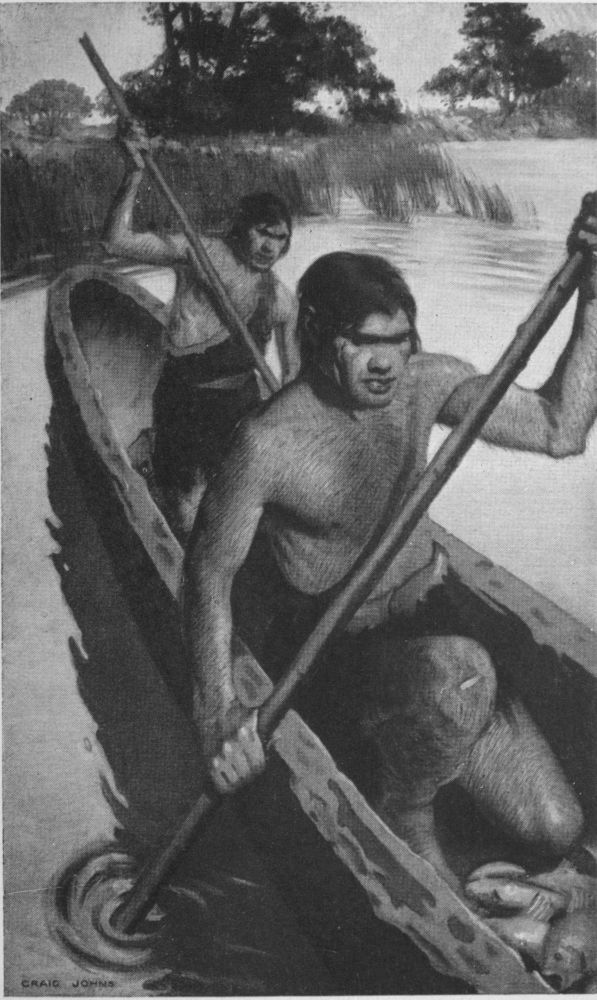

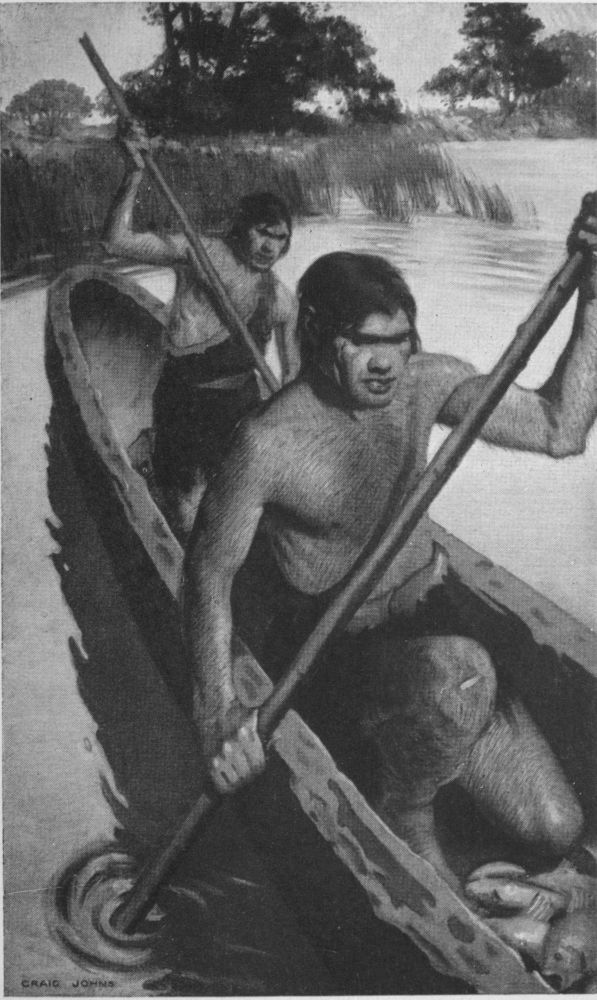

“With long poles thrust to the bottom, we guided the boats here and there about the shallow waters.”

Very wise is Thin Legs. None of the rest of us can think as he does; none of us can so tell what is going to happen after you have done things. Now he rested a little. Upon the top of the great log we had cut away he built a little fire, and supplied it with dry fuel as it ate its way into the wood. When it threatened to reach too far toward the end or sides, he dammed it with wet mud, and so made it eat this way or that way, as he would have it, until of the huge log there remained but a thing hollowed and charred, with thin, strong sides and bottom. We pushed it into the water, and it floated high, carrying half a score of us at once. So came the first man-made boat. Now we could fish throughout the whole lagoon!

With long poles thrust to the bottom, we guided the boats here and there about the shallow waters, and had better fortune than ever before, spearing the fish at all their feeding places. Sometimes, too, we would guide the boats into the depths of the wild rice which grew in the water, and lie in wait there for the water-fowl which came at night. So our fortunes were bettered.

It was a wonderful boat, one we could pole through the water far more swiftly than we could the other, and it seemed as if there could be nothing better. But we did not know. Not a great time passed when a strange thing happened. It was that I saw foolish boys make the clumsy boat we had before move in the water without a pole. We could make a boat move in the water only when we thrust down a pole to the bottom, and leaned against it and pushed; but the idle boys, playing in the one lying by the bank in the still lagoon, began pulling a flat stick through the water beside them, and the boat moved out, and then they were afraid, and yelled loudly, for they could not get back to shore. We got them back, poling with the only other boat we had. It was all most foolish, but I wondered. I saw the boys pull the flat stick through the water, and saw the boat move. I, myself, saw it. After that, I sought the flat stick the boys had used, and looked upon it and all over it carefully. It was just as any other flat stick.

When all were gone into the caves or the wood I took the stick and got into the boat myself; but I carried the pole with me, and laid it in the boat, lest without it I could not get back to shore. Then I took the flat stick, and thrust it into the water, and pulled backward with it, first on one side of the boat and then the other, as we used our pole, and again the strange thing happened, for the boat moved on the water as it had done with the boys! Farther and farther it went from the land, and I took up the pole with which to push myself back, but it would not reach bottom. The flat stick had carried me too far. I was frightened. I knew not what to do. I yelled, but there was no one to hear me. I was afraid of the water.

Then, in my desperation, I took the flat stick again, and pulled with it in the water, and the boat went farther, and soon, as I looked about, I saw that I was close to the wood on the other side of the lagoon. I pulled with the flat stick again, and the boat touched land again, and I climbed out and lay down upon the ground.

Long I thought. Could the flat stick make the boat go back? I would try. I clambered into the boat, and turned it about with the pole, so that it pointed toward the other shore, and then took the stick and pulled with it in the water again, and was carried back to very nearly the place from which I had started. I sprang upon the bank, and yelled and leaped up and down. I wonder why it is that men always dance up and down and yell when they are happy? The other creatures do not act in that foolish way.

So I danced and whooped, and then, finally, I became tired. But I was the greatest man in the tribe. I alone had the flat stick, and none should take it from me. There was another flat stick lying on the shore, and I took it up in sport, and got into the boat with it, laughing, because I knew it would not make the boat move. I was wrong. I pulled with it as I had with the other, and, behold! the boat moved as it had done before! Other flat sticks I took then, and pulled with them, and the boat obeyed them all. Any flat stick would move the boat, if it were only to be pulled with the flat side against the water. I was no richer than any other man of the tribe. Then I tried to move the boat with round sticks—many of them—but it lay still. The sticks simply glided through the water, and the boat would not heed them.

I shouted again, still more loudly, because I wanted to tell about the flat stick, and Thin Legs came running from the wood where he had been gathering nuts and roots. No game had he, for Thin Legs does not often hunt, though he alone can chip the best arrow-heads and spear-heads. I told him of the wonderful flat stick, and all it had done, and there came the thinking look in his eyes which I do not understand, and then he tried the flat stick himself in the boat, and then climbed ashore and leaped and shouted almost as wildly as I had done. After a time he sat down upon a little rock, and sat there long, saying no word, holding the flat stick in his hand, and looking at it. He could think long. It did not hurt his head as it did mine, and the heads of others of the Cave men, if we thought too much. Then we went to the caves together. Thin Legs carried with him the flat stick, but he said nothing.

When I left the cave the next morning the big yellow thing that makes the light had not yet come up above the great forest to the east. I could not wait. I was too eager to try to go upon the water again with a flat stick to move the boat. I ate but a mouthful or two of the flesh of the little deer I had killed in the ravine in the hills, and then I ran to where were the boat and the flat sticks. I took my bow and arrows with me. I would get across the lagoon, and go into the beech wood where many birds fed on the nuts, and where it was good hunting. There was no boat there! Then there came to my ears a yell from the other shore.

I called aloud in answer, and from the shadow of the distant bushes across the water came out the boat with Thin Legs kneeling in it, and digging the water, as it seemed, with a flat stick again, and the boat was coming toward me. But far more swiftly and straight it came than it had done the day before, and I knew in a moment that Thin Legs, the wise, had been at work in the night, at work by his fire in the cave, and that, somehow, he had given more strength to the flat stick.

It was the same flat stick at one end, but not at the other. The day before it had been hard to grasp and hold, because it was so broad, and I could not get my fingers round it. I could hold it only with a hard clutch, pressing on each side, and so could not pull it through the water without a strain. Now it was another kind of stick. All night long Thin Legs had worked with his stone hatchet and with his knife. For what would be the length from a man’s foot to his knee he had chopped and chipped on each side of the wood until there was left something that could be clasped easily in the hand, and this part he had cut and scraped until it was round, like a spear-handle. At the end was still a flat stick with which a man could pull in the water with all his strength, grasping the round handle above. No man had seen such a stick before, and I spoke not, though Thin Legs grinned.

“We will call it a paddle—which means what pulls,” he said, and grinned again. “Get into the boat.”

I got into the boat, and took the strange stick, and dug it into the water, and pulled swiftly with all my might, and the boat shot away as do some of the swimming birds upon the water; for now I had my grip and I was strong. I went to the other shore, and, very swiftly, back again. What a thing had we!

And another paddle made Thin Legs, so that we each had one, and day by day we learned about the boat and the flat stick, until, when we pulled together, we went over the water like the queer clacking water bird of the rushes, which need not fly from danger, so swiftly can it swim.

And all this time, in the day, was Thin Legs toiling upon a new boat, the little boat for us two alone, which should be greater than the boat the tribe had already made. All day he toiled, chipping with his stone axe, and burning with little fires covered by wet clay, that the fire might not reach too far, and each night I brought him food—nuts and berries and meat—for I was as eager about the boat as he. And, one day, Thin Legs declared the boat was done.

It was a wonderful boat! Never before had such a boat been seen. Not great in size was it—only the length of two men, and but broad enough for one—and each of its ends was pointed like the other. But it was not that which made the boat so marvellous. Long and patiently had Thin Legs laboured. Much had he chipped and burned, and so watchful had he been that the boat, smooth on the outside as the shell of the river turtle, was itself but the thinnest shell, alike in thickness throughout every part of the tough wood, yet as strong as the clumsy boats we had already made, and so light that one man alone could carry it. Even Thin Legs found it not too great a burden. To me, Scar, the Strong One, it was as nothing. Yet this shell thing could easily carry the two of us upon the water, and a considerable burden besides. Very wise was Thin Legs.

Wondering were the other Cave men when we put our boat in the lagoon and they saw how great indeed it was. Many days we practised, and learned to paddle, alone or together, and to turn the boat this way or that as we willed. We might, we thought, even venture upon the deep river, but we were not sure of that yet. Some day, though, we would make the venture; though far down the river, so the old men said their fathers had told them, were a strange people, who lived upon the shell-fish they dug from the sands of the shores and who were very fierce, and slew all strangers, though they had no bows, but only spears and axes and stone knives. Of all these things Thin Legs and I talked much, but we had no thought of going upon the deep river at this time.

For a long time we used the boat, going where we would in the lagoon, and spearing the fish, though many we lost, because our spears would not hold them well; and great hunting had I in the beech and oak woods on the farther side, which we could not reach so easily before, and where the bush birds, and the cock that struts and calls, and all the creatures that feed upon the nuts and berries, were not so fearful as those on the side of the lagoon where were the caves, because they had not been hunted so often. Close upon these creatures I would creep, and drive my arrows through them; and we would come back to the caves with much meat. And there was none among the hunters who matched with me, Scar, the strong bowman. Then another great discovery.

I had shot and killed a porcupine, and went back to the caves with him most carelessly; and because there was more than I could eat—he was a very fat porcupine—I called to Thin Legs to come and cook and eat him with me. I was careless, and one of the spines, the things upon the back of the porcupine, slipped into my thumb, and I could not pull it out again from the flesh below the first joint. Thin Legs tried to help me get the piece of porcupine out of my hurt thumb; but it would not come back, though we pulled, and it hurt me, and I yelled. Then suddenly I pushed it—I don’t know why I pushed it—and it went easily and smoothly. Thin Legs took hold of the other end of it, and pulled the great quill through without hurting me at all.

The next day we took our little boat, and rowed up and down all around the edges in the yellow, shallow water, and, with our flint spears, speared many of the fishes; but many of them slid off—not all of them, because sometimes we used to toss them swiftly into our boat or to the bank. But the most of them slid off; and though we were very keen of eye and deft of hand, Thin Legs and I, we never got the half of them.

But something came into my mind that afternoon, and I looked at Thin Legs as we lost fish after fish, and rowed to the shore with him, and sat down on a little rock, and then I asked him what it was that made the quills of the porcupine hold things so.

He did not answer, but thought a little. There came the distant look upon his face again, as if he had found something, and then, with a shout, he leaped up, and began running toward the cave. I paddled back with the boat and fish, but I did not see Thin Legs again that day. He was working in his cave, and would allow none to enter it. In the morning I knew. All night he had worked, and he had chipped the heads of two flint spears so that they were barbed, as were the quills of the porcupine, only in a far coarser way. Then I knew. Never had been such spear-heads before, nor any worth so much in food-getting! How can I tell the story of the Barb?

We went to the lake the next day with our spears—for Thin Legs had made another like the first one—and we rowed in our boat among the shallows, and there came beneath us the great fish; and we speared them, and none of them slipped away, because of the great barbs at the side of our flint spears.

Very heavily laden was our boat, for it was full of fish when we paddled back that day, and very rich in fishes were we now, and great men in the tribe were Thin Legs and I, because of the spears which held the fishes. There would soon be other spears—very many of them—like these spears that Thin Legs and I had made; but that does not matter. After this, in all the time when the winter had not come, there would be fish enough to eat in the caves. So Thin Legs and I were very proud as we strutted along the narrow pathway below the caves and close to the water where the frogs croak so oddly in the weeds of the sloping bank. The boat and the barb were ours!

There is a curious white fish, very tender and flaky, and sweet in the mouth, which gathers in schools in the big river just above where the swift current begins, and it came to me that I might go among them with tied lines and barbed hooks trailing from the boat, and so catch at least one or two of them. I wanted Thin Legs to go with me, but he declared it to be unsafe. If once the current got hold of the boat too strongly, he said, it would be carried down the river and over the falls and upon the jagged rocks where no man could live; but I only laughed at him, and said, since he feared, I would fish alone. I took my lines with me, with bait for the barbed hooks, and tied one end of the lines about my waist, letting the hooks float in the water far behind. When I heard the roar of the falls, I became afraid, and wished to turn the boat to row back with the floating hooks; but I found all at once that I had come too far. As I strove to turn, the fierce current caught the paddle, and exerted its strength against me. How could Thin Legs have chanced upon such treacherous wood? The paddle snapped short in the middle, and I was helpless with the fragment of the handle in my hand. The boat whirled round in the rushing waters. The falls roared more loudly. There were the jagged rocks below, and certain death there. I threw myself along the bottom of the tossing boat, lest it overturn even before the leap. But of what avail? There was only death below!

I closed my eyes, and, with a roaring of the waters in my ears, shot downward toward the jagged rocks, and then came nothingness.