CHAPTER XII

THE SAILORS

I had been sleeping, pleasantly enough, though dreaming of a noisy clanging of hammers in a forest. I awoke to find myself stretched lazily upon the sand, to hear the lapping of waves and look out upon blue waters to the westward, it must be, for it seemed afternoon and the sun was not far above the waters, a little to the left as I faced it. I rose to my feet and looked toward the east and there saw a host of palm trees, beyond them green hills, and beyond these, mountains. From the beach the land lay level to the hills and, not far from the shore and among the palm trees, were many huts with people moving about among them. Near where I had been lying were a number of boats hauled out upon the sand, which boats I studied curiously. They did not seem unknown to me, but I was still half-sleeping, for the sea and the air and the day were drowsy, and the leaves upon the palm trees were idle.

Not from the trunk of some great tree had any one of these boats been hewn and hollowed. They were made in quite another manner, with a framework, and keel and ribs of heavy wood, and a sheathing, with the seams made water-tight by caulking, and carried oars instead of paddles. Very good boats they seemed to me, and fit for riding rough water, and, as my sleep-clogged senses cleared, I knew, for had I not helped to build them? Most excellent boats they were, and I could see still larger and finer ones drawn to the beach at a greater distance from me, and others riding the waters of the fair harbour made by the semicircling curve of land. From where the larger boats were hauled up to the shore there came a shout:

“Haste thee, Scar; we go out for the fishing!”

I hurried toward the boat, for I knew what was my present duty since there were but six of us to man the boat, which made but a scanty crew. We were not to row far, however, only to a place nearby the islands where the fishing was most promising, so that all the oarsmen usual were not needed. My companions were already in their places when I reached them, and lightly chided me for my delay. I took my seat upon the rowing bench and grasped an oar and soon we were sweeping toward a passage between the islands. There were in all the world no better seamen than we of the Phœnicia which had begun to live fairly with the founding of our village, Akko.

We were not great people as compared with these who were behind the mountains of Lebanon, which protected us on the east—there were as yet but some five thousand of us to occupy the narrow land between the mountains and the sea—but we had prospered greatly since venturing from the home of our forefathers, where the great Euphrates finds the southern ocean. It was well for us that we had found this palm and wild vine-clad country, rock-walled and safe as might be from invasion, and had taken up our abode here, and sent to our kindred telling them of the soil’s richness and of the many spoils of the sea, and so they were following us, band after band, forming new villages to the north along the coast. Of these were Sidon and Tyre, though as yet they were but hamlets. As for us in Akko, we could ask no better fortune than was already ours. We were possessors of only this close-bounded and curtailed domain—but what a land! Never was one fairer or richer or better suited to the needs of such as we. The palms which grew in forests along the sea-lapped sand and wide beaches supplied abundant timber for our houses, while for our ships!—already our great biremes were becoming stately—there were the cedars of Lebanon thick upon the range behind us, and oak and other woods of strength. Back of the sandy coast belt was the fertile plain, yet to become a region of gardens and orchards and cornfields, a land for the pomegranate and the orange. Still further back rose the green, low-lying hills, great slopes whereon would grow most healthily the vine, the olive and the mulberry, all of which we cultivated zealously, and then, as the hills rose into mountains, came the ruder spaces clothed here and there with forests of oaks, chestnut, sycamore and terebinth, and, best of all, the mighty cedars, of which I have already told. There were harbours at points along the coast, made naturally by the many small islands which formed a barrier against the incoming sea. We were settled in a land of abundance and one also of safety and security, for from the mountains at the south ran out a great promontory ending in a precipice at the sea and rounded by only a narrow path, while to the north were defences, raised by nature, not less formidable. To the west of us in our front lay the great sea, the Mediterranean, as men learned to call it, blue as the sky above it, teeming with the fish we needed, and treasure-bottomed because of the rare things which, by lucky happening, we found there. Far in the offing above the tideless waters could be seen a dim blue speck where the sky and water blended, the island Yatnan—the Cyprus of the future—an island of kindly people to be some time followed by others called the Greeks, with whom we were already beginning to do a little trading.

For we were traders! Traders, boat-builders and sea adventurers were we, above all other peoples. The world had learned to barter, it may be from those who had first discovered copper, which all men needed and for which they would exchange that which they had, and we were those who had already made bartering our chief and earnest occupation. This had been the way with us even at the mouth of the Euphrates, whence we had come and where between contemptuous Babylonian and rude Assyrian we had been much oppressed, and so had fled to find this treasure strip. Warriors we had never been, though sometimes, at bay, we had fought well, nor had we been skilful hunters within the memory of our generation. Dark-haired and swarthy, sprouted from an ancient race to the south, some said, we had come to this new land to make, if we might be favoured of our dark god, a better future. Most skilled were we in the many arts, but better still, for us, in traffic in that which we made. We dealt much with the stronger races which endured but did not mingle with us. Now we were to trade from our own land as a vantage ground. The outcome was what no man could dream.

We had built our houses at Akko and had sowed our fields and planted our trees and vines and had builded our boats, and in them had already begun to range the coasts for such trade as might be found, though not so far at first, because as yet we had few goods for barter save the fine linen which the women wove so well, and wool, and cedar timber, and besides, we were not yet acquainted with the strange shores. Our first trade, as I have said, was with the people of the large island Yatnan, which was so near to us, and from this alone arose in time a mighty business of ours, for in Yatnan was much copper, and the people were such we did not fear. Soon, too, there came to us such aid from what the sea gave us, that our traffic, we were assured, must surpass all we had hoped for, our fabrics having given to them suddenly a value never known before.

The bireme in which we went to the fishing was shared with me in its ownership by my comrades Aradnus and Malchus, and it was to Malchus that our people owed a part of their coming vast good fortune. Malchus had many fancies, and among these was one for a collection of the glittering different shells we found upon the shore or in the waters we dredged for shell-fish, of which there were many edible and nourishing. Once in an oyster he had found a pearl of quality, and so it came that he was ever curious to learn what his shells might hold. Much we derided him for his useless searching, but he made answer only that there were many things yet to be learned, and the issue proved him right. Among the shell-fish counted useless by us, because we found them tasteless, were two kinds, each of spiral form and ending in a rounded head, but one sort more rough and spinous than the other. It was after breaking one of each sort of these twisted shells that Malchus discovered a curious thing.

With a stone, Malchus cracked the shells apart upon a smooth rock where he could observe them closely. That of one sort thus broken and the creature within it shown, there appeared a shell-fish having a sort of sac behind its head, this sac extending into a sort of vein traversing the body, the whole filled with a liquid whitish in colour and having the smell of garlic. This liquid chanced to gather in a tiny pool in the surface of the rock and, even as Malchus studied it, wondering what its use to the fish might be, it changed before his eyes, as the air reached it, from yellow-white to green, then blue and red, then a deep purple-red and, finally, to crimson, which last colour did not pass away. In the shell of the rougher kind he found a creature with a sac which showed also changing colours, though somewhat different of shade. Much Malchus wondered and, at last, he sought a piece of linen and dipped it in the liquid and found he had a cloth of brighter colour than ever known before. He had discovered a wondrous dye! More of the shell-fish were soon collected and there was much experiment with the dyeing, for we all were full of interest now, and it was found, in the end, that by first dyeing with the matter in the sac of the smoother shell-fish, which was abundant on the rocks near shore, and later with that from the rougher kind, which was found in deeper water, there was gained a purple so royal and brilliant that no other in the world could by any means compare with it. Dark and rich it was, like red blood cooled, and, as it was shifted in the light, a blazing crimson. The rocks and the sea-bottom were covered with myriads of these strange shell-fish, which we caught with baited basket traps let down, and soon our varied cloths gleamed with such hues as would command the desire of all who might look upon them. A marvellous new thing had we for barter, and in the end it brought great fortune, though not all of it remained to Akko. There came a time when vast beds of the shell-fish, and of even more productive quality, were found near swiftly expanding Tyre, and great dyeing was done there, and trade came widely in the colouring and its fabrics until priests, senators, emperors, and the great of all the known world must garb themselves in Tyrian purple as most worthy of their dignity. Surely never were a people’s fortunes so affected as were ours by what might be deemed so small a thing as the juice in the head of a sea creature!

But this discovery of the purple dye had but lately come and diverted us only a little from a host of things of greater purport. Our boats and our plans for our sea-roving as we might extend it, were what absorbed us chiefly. Nowhere were better boats than those we had already learned to build, but we were ever seeking their improvement, since our fortunes were dependent upon them. Biremes, as our boats or ships of the better sort were called, were better than those owned by our fathers, not short and rounded and caulked with bitumen, as had been the boats of only a little time before us, but longer and caulked with tar, which we had learned to make, and, in our latest ventures, double-decked so that the oarsmen could work below while their masters were above them. Good ships were these, riding the rough seas well, and much we prized them. Our only lack was in the oarsmen. We needed galley-slaves, and had but few, and oftentimes the trader and his people must needs take care to the oars themselves. As for me and my companions in sea ventures, we had but two, dark creatures we had found castaways upon a bare island some distance to the south, and certainly of some poor tribe, for the broken canoe we found with them was crude of form and by no means fitted for a sea trip. Blown away they doubtless were from the great continent which bounded the sea on the south, a land almost unknown to us, though we were somewhat acquainted with the people, ancient almost as we, who dwelt on the shores of a great river with many mouths which came into the sea not far from its eastern end. Intelligent the captives proved, in a slow way, and docile enough, though possessed of enormous appetites, which we must gratify or else lose of their strength in the rowing, but which were nevertheless somewhat of a burden on us. However, we hired them to the husbandmen when not upon a voyage, and so regained a little of their keeping cost. We were ever thrifty, we Phœnicians!

More slaves we must have certainly, and it had been resolved, not only by us of the Spearhead—for so we had named our sharp-prowed boat—but by others of the traders, that cruises must be made with that end alone in mind, and it was considered that we might find what we sought in some of the islands which lay beyond blue Yatnan, some of them very small and having on them, very probably, so few people that we might make our foray safely and bring away as many captives as our ships would carry. For this we were to band together in a fleet and join our forces in whatever conflict came, afterward dividing the captives by lot or in any other way we might agree upon. It was while preparations were making for this same expedition that happenings came which greatly changed our plan and had a mighty bearing on our future ways.

One of those who were to take part in the expedition was a most daring and reckless captain having the name of Neco, who but a little before this time had made a voyage to the southward and brought back with him to Akko a cargo of hides, for among us were skilled tanners and cunning workers in leather who supplied many things for our trading, and hides were always desired by them. It so chanced that upon the return voyage of Neco some of the hides which were green and like to spoil were stretched between poles set upright on the deck of the vessel, and that the wind from the south, bearing hardly upon them, pressed the boat most swiftly homeward, the craft requiring only to be steered. And this gave Neco a great thought, and he swore by Moloch that henceforth the wind should serve him and that the labour of the rowing should be so avoided. So vaunting was he in this that he declared that he would yet reach Yatnan and thus return, and the marvel of it was that he did as he had boasted, sailing one day when the wind blew strongly from the east, and returning when it had shifted to the west. Now his pride became overweening, and, having made a great sheet from broad strips of linen sewed together, he spread it nailed between tall uprights and set sail to the southward with a fierce rising wind behind him. His ship disappeared amid the mist and spindrift and nevermore was seen of man. The blast must have been too much for the fixed sail, and the vessel must have buried itself beneath the waves which rolled high upon the day which was the last of Neco.

It would seem as if the fate of this wild adventurer should have brought pause to any who had thought to do even as he, and to call upon the wind in aid in passage of the sea paths, but with me it was not so. Eagerly had I noted the feats of Neco, and it had been borne in upon me that there was a degree of wisdom in his madness. Even his death, of which we became assured, brought me no fear. I, too, would seek to learn what might be done to make the wind our servant, and I set about this swiftly, being to my wonder well supported by both Malchus and Aradnus, who sometimes showed less hardihood than I, but who now, strangely enough, became as deeply lost in this dream of a new conquest for the toilers of the sea. We devised a curious plan whereby we thought we might try the issue with less risk of our lives than had been faced by Neco.

We knew that the greater danger from the wind was that the boat might capsize in a storm, and our first care was to avoid this risk as best we might, though we were resolved to test these dreaded sea-blasts to the utmost. Truly we were half mad, but the zest of the thing had grown upon us. If the risk were great, the stake was great as well, and we fell together under some sort of spell of joyous madness over the prospect of we knew not what. And this was our crafty plan!

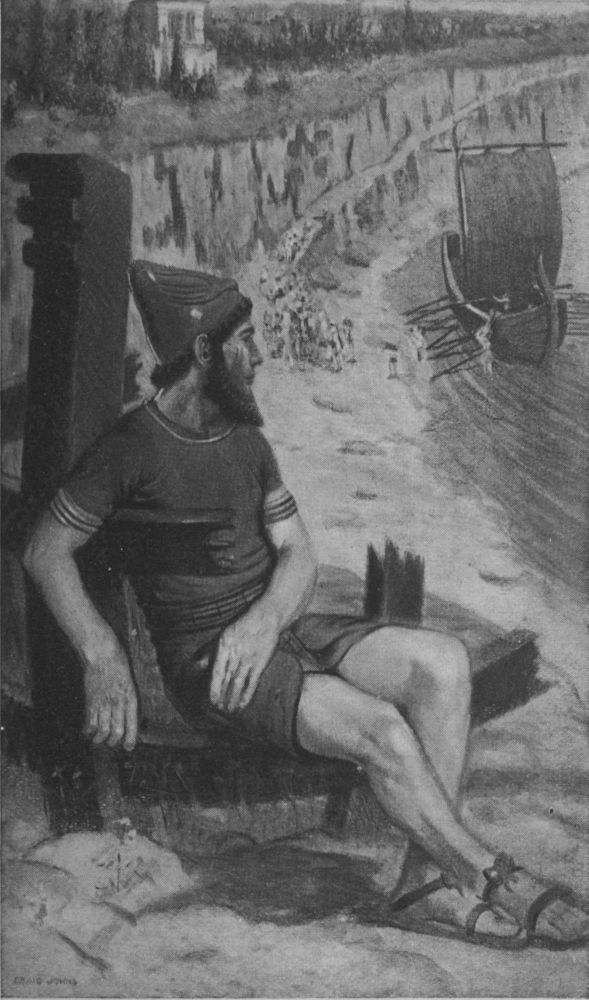

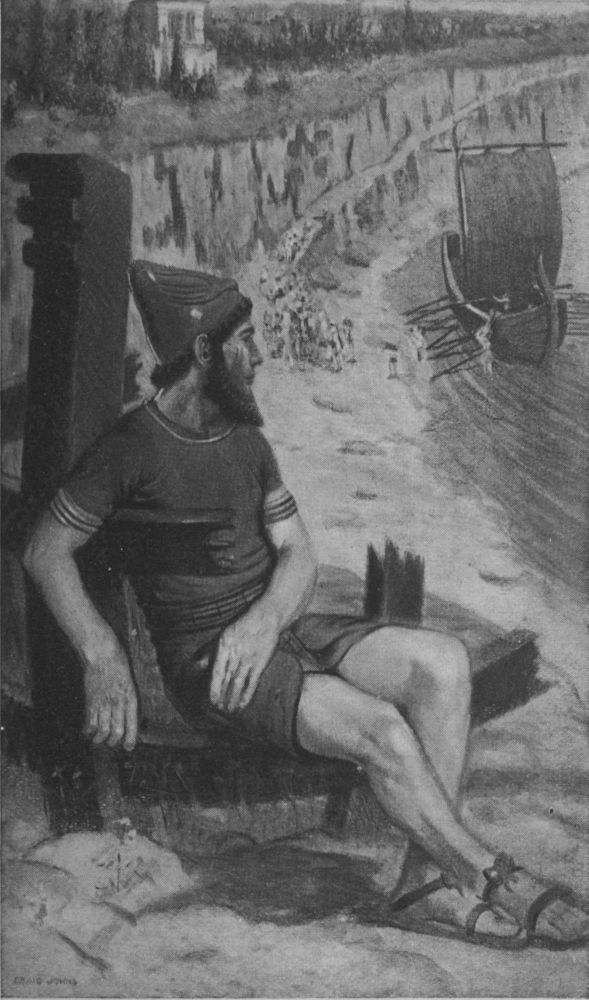

“I, too, would seek to learn what might be done to make the wind our servant”

Often when ships laden with timber had been cast upon the rocks and crushed, those in dire peril had escaped by lashing together as many of the floating beams as they could, making a raft which would not easily overturn, and so drifting by good fortune to some place of safe landing. Our ship, so we devised, should be a raft; yet more than that; it should be a sort of boat as well, but one unsinkable, and thus we built it, working long with our two slaves, and hewing and spiking the seasoned cedar timbers, of which there was a great store at hand for purchase and of which we owned a part. For many days we hewed and shaped and fashioned until we had a great raft some thirty forearm cubits long, more than seven times the length of a tall man, and more than half its length in width. Of double depth were the dried timbers and so mortised and interset and spiked together that the whole was as one great piece of wood not to be torn apart by the mightiest seas. Caulked it was, though needlessly, for we knew that the water would often come aboard, and all about the sides was raised a stout timbered wall of the height of a man and having many openings at its bottom that the water might escape and we might walk dry shod when seas were calm. So much we allowed the strange craft the nature of a boat that it was tapered to a prow at either end and, furthermore, was hewn so that each prow swept upward from beneath, that the boat might rise on any sloping shore. At each end provision was made for a long steering oar such as we used on the biremes. Upon either side, amidships, was erected a stout mast between which the broad sail of strongest linen was stretched flatly, and in the centre was a shorter mast to which were bound many things which were to form our cargo. There were other short posts as well, placed here and there to serve a like purpose. We carried our arms and much food, and many lashed casks of water we provided, and certain chests of trinkets and some of more worthy things to barter; for we could not guess what might be our landing-place should our plans fail. It was decided to attempt the voyage to Yatnan and thence homeward as our first venture. So, one afternoon when the sun shone most fairly and the wind was from the east, we cast off the long mooring-rope and were blown gently away to sea, while half of Akko stood looking upon us curiously or jeering at our uncouth vessel.

We were steering for Yatnan, as we thought, but many are the things in the laps of the gods.

Like how many things is the sea! It is like a woman, soft and smiling and caressing, at least upon the surface; it is like a stallion pawing and tossing his white mane; it is like a green forest bending and heaving before the wind; it is like an unbounded sheet of shimmering, supple glass, supine beneath a calm; and, at last, it is like a herd of wild beasts, roaring and hungry and devouring. Let none count our Mediterranean as harmless as compared with the mighty western ocean. The leopard is more treacherous than the lion! Much we knew already of the changing sea, but much more were we to learn!

The eastern wind, still strong and even, bore us steadily, though far from swiftly, away from our own coast until the shore line became dim, and, since it was so squarely astern of us, we found no difficulty in steering straight for Yatnan. Even with our laggard movement we should reach the island by daybreak, and this sailing seemed, in sooth, an easy matter. My companions laughed and jested, and the two slaves, relieved of all rowing, were agrin and happy. Then the breeze abated somewhat and the wind began veering here and there, and the raft-ship lost something of its headway, while the oar with which I myself was steering became more and more an ineffective thing. Most irresponsive to guidance was yet our new ship upon which we had so laboured in the building. There arose a little black cloud in the far northwest, and, somehow, I liked it not. I wished for the bireme!

At last the breeze died away altogether and we lay there rocked as gently as a first-born by its mother. The little cloud in the northwest was becoming somewhat too lusty for my taste, but as yet there was no sign of really dangerous weather. So we swung and swayed until the sun was low down in the west, and then the lightness changed to something more sombre very quickly, for the cloud had extended itself ambitiously, and the sun’s last slanting rays we failed to get. The breeze, too, had returned, coming this time from the north and having a greater and increasing vigour to it. The raft began to act with even less obedience to the steering oar, strain I ever so hardly, for the sail now took the wind endwise alone, and this could not avail. Not long did this continue. The waves had begun to rise, though by no means roughly, and the end of the vessel where I laboured was caught and twirled by one of them so smartly that it lay in a new way, and in a moment the wind had caught a hold upon the sail again and we were turned fairly about and headed for the south, stern foremost, if, indeed, we might be said to have a stern, since the ends of the craft were alike in every way. We had but one resource. The steering oar was shifted from what had been the stern to the end now made so, and we were sailing again, with oaths or prayers in our mouths according to the impulse of each. My own mood was not greatly either for oath or prayer now. As the uncouth sail filled or tautened and the boat leaped forward as clumsily as it did strenuously, the wild, fierce sense of abandon and utter daring came back upon me in a wave and I whooped aloud in zest of it, my comrades catching the wild unction and yelling as loudly in the same headstrong spirit. Often since have I thought of that audacious moment and wondered if such lifted moods might not be sometimes but the flaming out of a new man and a greater one, to make the most of dangerous opportunity? Have not the best deeds been often but the issue of an outbreak, foolhardy and desperate it may have seemed, of some strong man inspired by that for which he could give no reason? And, launched into some course of hazard, has not man often been so sustained throughout it that he has won his way, laughing or cursing at every jeopardy, until he has accomplished that which was good for him and for his kind as well? Truly the gods have curious ways!

So drove we southward half through the night, when again the wind changed, this time carrying us to the westward, though so gradually that Malchus, who had replaced me at the oar while I lay sleeping, held it so skilfully and firmly that the stern was still the stern, with which feat he was much delighted. With the morning the sun was shining again, though the wind had not abated.

All day we ran westward upon that sea of low-rolling waves, a sea so smooth that no water came over our boarded sides, and farther and farther we were carried from land or means of succour in any greater peril, but I lost none of my heedless ardour nor did either of my companions fail me. Especially was I delighted with the usually silent and thoughtful Aradnus, who, strangely enough, seemed to enter most fully and delightedly into the spirit of the trying of the sail.

“It is well,” he shouted to me, as the thing bellied as far as it might before the wind, and the foam arose a little beneath our low prow. “We are getting much wisdom, and more is coming to us! Mark what it does!”

And well indeed marked I that sail. I did naught but study it and note its tremendous promise, and its failings and its menace. As I studied, there came to me slowly a new perception. Why were we so helplessly at the mercy of this spread of linen when the wind blew? Why had we stretched it thus immovably across our raft-ship? As I looked upon it there came such comprehension as made me laugh at myself in sheer derision. Man, not the sail, should be the master, and there must be a way to make it so!

This I had noticed, that when the wind changed but a little, and so smote the sail somewhat aslant, the raft still held by the steering oar, kept straightly on its course, but when the shift was greater, so that the pressure came more nearly abeam, there ensued a sudden stoppage and we washed about unsteerable until there came another change. This, then, I had learned, that it was not necessary that the wind should bear squarely on the sail, but that a slanting pressure would do almost as well and still allow us to direct our course. Then, why not have the sail so that we could get such pressure at all times if we willed and so have ever steerage-way? Much I pondered upon this and at last I perceived what I thought might be the remedy.

I have not yet told, save generally, of what we had on board lashed to the many posts, for there had been abundant room and I had made provision for many things. There was one long chest in which I had placed, besides our weapons, a goodly number of tools such as we sailors used, with the thought that, should we be cast ashore, we could build shelters for ourselves, and glad I was now that I had been so provident. More time we would not waste before I had carried out my new design, and so I explained its nature to the others, who comprehended what I had in mind and who at once began the labour with me.

The two masts to which the sail was nailed were set deeply in holes mortised squarely through the timber on either side, but, though tightly, not so that they might not be lifted out by the heaving of good men. Now we took chisels and hammers from the long chest and began the making of similar square holes in a great circle amidships, the diameter of which was the width of the broad sail. It was a task which took us long, but the sea was calm, the chisels sharp and the hammers heavy, and it was done at last. Just as we had the task completed it chanced that the wind shifted so that it came squarely over one of our sides and left us wallowing again. It was not for long. We strainingly lifted the two masts from their sockets and so replaced them in the new receptacles that the wind, though coming over our side, struck them obliquely and thus again propelled us while the helm oar kept us straightly upon our course. It was a revelation. The sail was being, for the first time, tamed! But there was more to come, and that at once.

I sat upon one of the chests after our first moment of jubilation and watched with pride the issue of the conquest we had made, when there came to me a new idea beside which the first, so carried out, seemed only a beginning! We were ploughing merrily westward now, but westward it was not my wish to go. If, now, the wind, coming from one side of us and pushing upon our sail obliquely could so carry us, as it were, athwart its course, why could it not, in the same way, take us to the eastward, were the sail turned so that the pressure of the wind would press in the opposite direction? I leaped to my feet shoutingly and told of what I had conceived, and forthwith we acted. The masts, or, rather, one of them, was raised and so shifted that when it was planted the sail took the wind upon the other side, and at once we lost headway quiveringly, and soon were sailing eastward! Truly it was a great day in the history of sailing, and one of vast moment to all traders and sea-rovers!

Of where we were, save that we were far from land, I had slight knowledge. Full half the way across the sea we must have come, for the north wind had been a strong one while it prevailed and had hurried us for many a league despite the heaviness of our sailing. The westward course, as well, had been with a southward trend and it seemed to me that it were much easier to find a port on the African shore than otherwise. But what manner of port might await us in that strange region? Most barbarous tribes, so the Egyptians had told, inhabited the long reaches of sandy or rocky coast, and luckless were those who landed there. I had no plan we were undetermined of mind as the gulls which swept about us, but land of some sort all men who eat and drink must some time find or perish, and we were not equipped for very long. I counselled with Malchus and Aradnus and, in the end, we acted not unwisely, as the event proved, though there was much to come between. Somewhat we knew of the Egyptians, for between their land and that by the Euphrates there had been a little trade, vast as was the distance to be traversed, including the passage of the strait between the seas, and we knew them as advanced in ways of learning and as generally peaceful. They were unlikely to set upon such weak adventurers as we and of a race which they knew. So it was decided that we should bear to the southeastward straightly as we might and seek one of the mouths of the great river which we call the Nile.

The wind held as it was, and slowly, though steadily, we moved toward the east all through the afternoon of this day when I had devised the shifting of the sail, and toward nightfall at a swifter rate, for the sky was now becoming overcast and the wind was rising. Soon there were mounting waves, and the raft-ship, as I have called it for want of a better name, began to rise and fall in its now more hurried progress and to occasionally dip its prow into the sea and take aboard much water, which did not harm us, since it at once washed out again. We would have been content with this mood of the wind and sea had it but remained the same, but that was not to be. The storm-god was abroad that night, and drunken!

There be certain men among us Phœnicians who have great gift of words such as I have not, and who can write most eloquently—for we have letters and learning which other peoples lack—some one of whom might, it may be, have described fittingly the storm of that dread night had he but been aboard our raft and had not died of fright, but much I doubt it. There is not stylus to trace the tale of such storm as that in letters! Whereas at the beginning I longed for our staunch bireme beneath our feet, yet long before the morning I thanked the gods that we were lashed firmly to the posts upon our strange new vessel. What a sea-mew proved our riding craft that night!

The wind became a gale, and the gale a most tremendous one. Each man of us was firmly lashed to a stout post, else we would have been inevitably lost. Down one great wave we rode or up or through another, and that we did not drown was only that between the billows we had a chance to gasp for breath. For hours we were thus hurled forward, and when, toward morning, the storm somewhat abated, the change came none too soon, for we were spent to the verge of certain death. Now the raft riding naturally so lightly and so easily, no longer buried its low prow in the oncoming surge, and we could at least breathe steadily again. The worst was over, yet by no means all the trial, though we had no fear. Our wondrous raft had shown its worth in that it could not sink nor capsize. What more could reckless adventurers ask? Still we climbed the towering waves and still rode down them, rushing to the southeast, but we feared now less the water than the land. It was not a proper sea in which to find a threatening coast. Very narrow was the slant of canvas we now allowed to catch the wind, though to shift the sail with such foothold as that uptilting or descending deck afforded was a feat of catlike merit.

Exhausted, we slept by turns, as best we might, still lashed for safety’s sake; and when, at noon, I was aroused by Malchus I looked with pleasure out upon a sea which was not threatening. More, too, I saw. To the southeast appeared afar a blue haze which, as we sailed, revealed itself as a low-lying coast, and, furthermore, a coast revealing the mouth of a broad river, one which could be nothing else than one of the outlets of the mighty Nile! I could not be mistaken, and for that mouth we steered. Our fortune had brought us as fairly to our aim as if our course had been directed by the nicest seamanship!

The river entered the sea through the lowlands made by the silt of countless ages, and, for a league at least, we sailed up the deep stream between flat marshland. Gradually the banks became higher and palms showed in the distance, and at last we moved slowly up toward a place where were trees on the river’s western side, and there we contrived to land, one of the slaves swimming ashore with a rope by which we hauled in our raft, mooring it stoutly by other ropes tied to our posts. Far up the river we could perceive buildings of stone, and I knew it for a port of some importance of which I had been often told. The slaves we left to guard our vessel, knowing they would not venture to desert us in this strange land, and then we three—Aradnus, Malchus, and I—after having washed ourselves and donned fresh array from our scantily filled chest, fared forth to learn what Egypt should prove to us. We had no fears, because these were a people civilized, even as we, though not such daring wanderers. Already, through many centuries, had the sun shone on the great cities of the Nile, and the climax of the power of Egypt’s rulers was nearly at its zenith now. We reached the city, not a great one like Thebes, Memphis, or other cities of the upper river, but a prosperous out-lying port with promise of future trading for us.

There were many people in the streets, but we had not thought of recognition. Ever comes the unexpected. Conceive then how surprised I was to hear a call to us in the Phœnician language, as there advanced to me a swarthy man of middle age, a man of good appearance, who spoke smilingly:

“Welcome, Phœnician! Whence came you here?”

I could not understand, yet all was simple. The merchant, for such he was, explained to me that he had for years gone with the caravan to Babylonia, and had so in time acquired the Phœnician language. He declared also that he could at once distinguish a Phœnician by his appearance, which was, however, no marvellous thing, since the Phœnician face was racially distinct, and since we had traits of garb, trifling, it is true, but sufficient to make us somewhat apart in dress as in complexion and demeanour. There was much talk between us and, when we had done, it seemed to me as if that which could not be had taken place.

Here were I and my companions, who but a few hours ago were tossing about in a wild venture upon an unknown sort of craft, facing death in raging waves and doubtful of our future and our fortunes, now in peaceful harbourage, and, more than that, in a fair way to attain such ends as would enrich us and our people in the future. The merchant had promised much, and it was borne in upon me that he spoke honestly. At this port of Egypt, he said, there were not he alone, but various other merchants who would gladly trade with us Phœnicians; that they had learned of our occupation of the new land and of our prosperity and that they well knew of our ways of trading along strange coasts, so bringing to its market many wares which could not otherwise be gained. Readily would they deal with us and buy of us such things as would add to the merchandise transported by their caravans either up the great Nile to Memphis and to ancient Luxor and other places, or else would be taken with the rarer caravans to the rich marts of the cities of the Euphrates. What a prospect was this for us in Phœnicia, who were now seeking such broader ways of traffic! Gladly I assured the merchant of our constant future sailing with goods for Egypt, and so it soon came that I and my companions, through this helpful first acquaintance, met other merchants and made divers business pledges to them for the time to come. And one business of much profit and great promise came on the moment.

I have said that our sore need in Phœnicia was of more galley slaves, that we might be equipped for the trade we should soon command. Of this I spoke to the merchant, Thomes, he whom I had first met, and from him learned that he and his friends could furnish me sturdy slaves at such price as made foolish long voyages to gain them, such as we in Phœnicia had in contemplation. Gold we had with us, for I had counselled with my companions that we bring with us such of our wealth as we could carry, and we had it bestowed in belts about our bodies. Upon this store we now drew and therewith purchased twenty lusty slaves at a price which seemed to us but half, and forthwith bestowed them upon our boat and there provided them with subsistence while we awaited the time of our departure some days hence, for I had certain thoughts in mind which were of import. I had more to do with the sail!

Ever, when not engaged in the trading or informing ourselves in such things as might serve us in the future of the ways of these Egyptians, were we considering how the sail might be made a greater thing, and how a portion of the huge labour of its shifting might be avoided, or made more easy; and from these debates and from many earnest hours of puzzling and deep thinking, came at last some birth from my poor head. Our trading—for we bought certain Egyptian goods for sale in Akko—and our communing with the merchants ended, we left the port and set up tents on the shore beside our vessel and there began the labour which must follow my new thought concerning the handling of the sail and making it more subservient to swift occasion.

The labour had been great of moving the masts about upon our deck, and this labour it now came to me was needless, for by means of a single mast the sail could much more easily be shifted. And this, with much shrewd counsel from Aradnus, was what I now devised.

First, we raised amidship, though a little toward the bow, a single sturdy mast, and next we stretched the sail upon a strong frame, which frame was hung upon the mast, securely held by encircling thongs supported on outstanding pegs and so sustained that it might be swung in all directions, hanging thus firmly and flatly. To the middle of this frame at either side were attached long ropes to be pulled from the deck by the slaves, thus giving us the power to slant or hold the sail in any way the wind might call for. It was but a rude device—much better way did we later find for the sail-shifting—but it served us very well. I was resolved to return to Akko in our strange ship, though the merchants made ready proffer of one of their great rowing vessels to carry us by oars alone along the great stretch of coast. This would not serve us. Our slaves must be trained to the rowing, and so I had provided oars and the fastening oar thongs and seats along each side of our vessel. We might thus make our tedious way by oars alone, but we would not. The sail must have its further testing, and its control must be learned by all of us. Henceforth we must be sailors!

What need to tell the story of that grand voyage! The sail served well, though truly not as it came to serve us a little later, and the new slaves had learned their oarsmanship before we came into the bay of Akko. What need, either, to tell of the manner of our reception by our citizens? There was no longer scoffing, and when our tale was known to all there came excitement among all the captains concerning the trade with Egypt and there were made preparations for many sailings. As for us, we moved both mast and slaves to our bireme and prepared for much adventure. Soon, too, the other biremes, as well as vessels of lighter sort, were bearing sails, and, though crews were lost at first through too great recklessness in time of storm or through great ignorance, yet the age of long voyages by rowing had passed forever. Both I and my companions throve and, after some profitable trade with Egypt in glorious purple fabrics and in other things, and when we had builded another and greater vessel, a trireme, requiring many galley slaves, there came to each of us who had once faced the danger of the sea together a desire for new adventure and, it might be, graver peril. The lust of far roving had come upon us, and we would not be denied! We loaded the trireme with many goods and an abundance of arms and thus set sail to the west and north, for we would explore the shores of the vast continent there lying and harbouring, as we knew, a host of many different peoples, how barbarous we could not tell. We knew, though, that they had no boats with sails, and that we could flee that which we could not face. No man aboard but was gleaming of face when the Seeker, with white sail outspread and not a single oar outthrust, save those for steering, swept bravely from the harbour.

Never was voyage more curiously doubtful from day to day than this, and never one to prove more the index of vast happenings in the future, though that we could not know. We sailed at first discreetly, for we had some knowledge from the people of Yatnan concerning those of the islands beyond them, and with these we did not wish to have acquaintance at this time, for they had no cities nor any goods of value. It was the continent upon which we placed our hopes, for there were legends of ancient kingdoms there, and of peoples living upon the shores of the far western sea who were as old and as wise as any in the world, and owned fair cities and much riches. I may, even now, tell that we found none of these, yet there still exists the tale of an ancient country beyond the westward strait between the sea and the ocean, and which tells of how the ancient land, Atlantis, was swallowed by the waves. Of all this I know nothing, and doubt if it is known of any man.

So we skirted the many islands west of Yatnan and the mainland reaching down among them, and laid our course more straightly northward, soon to find ourselves in a long and narrow sea branching far upward from our own beside a long peninsula shaped like a boot. A great distance up this sea’s eastern shore we sailed, passing mostly rocky coasts, and rounding its far extremity and returning upon the western shore, where we found life indeed, but life of an almost savage sort. There came to the beach to meet us when we made a landing a band of scores of people, men and women, clad in skins and most abundantly tattooed in strange designs. Yet were not these people altogether savage and they were peacefully inclined. They had little for which we cared to barter even trinkets, and so we left them. Then came another sort of sailing and it was well for us that we were most skilful seamen now, for surely the voyage had its perils.

Westward, rounding the tip of the great boot of the peninsula, we turned, and entered a passage between it and a big island upon which a huge volcano was vomiting its fire and smoke. Here all our skill and courage found their test, for more desperate and dangerous passage could not be than that between the island and the mainland: fierce, treacherous currents threatening to cast us upon terrifying rocks on one side or the other. Very content were we when we came into the open sea again and laid our course upward along the western shore of this great boot. It proved a pleasant land enough, though we passed another huge volcano in eruption and rearing its sombre plume high in the heavens; and on making landing we found a people made up chiefly of villages of harmless fishermen whom we liked well, but who had as little to barter as those upon the other shore. So we voyaged still farther northward, and entered a river, up which we sailed but a league or two, seeking the reason for a smoke which arose there and which, we thought, might betoken some home of man. We were not mistaken. There were men and women there, lusty and vigorous, of two tribes in alliance and occupying a straggling double village scattered over seven close-grouped hills, through which the river ran. Here we lingered for several days, learning much of the people of this village—Roma, as they called it,—and of the ways of those who lived in it. They were a rugged people, most full of enterprise, and chiefly engaged, it seemed, in raiding the tribes about them. With us they became upon good terms and we made trade for such tremendous store of wolfskins as must make our voyage profitable. Little we could divine that in centuries to come Phœnicians should find here one of their greatest markets, and that Sidonian broidery should bedeck the robes of Roma’s fair women and Tyrian purple band the togas of senators and nobles and of emperors. We sailed away well satisfied. Not much farther did we make this voyage reach, though sailing a day or two westward toward the strait leading to the unknown ocean, and finding naught to induce a landing. Then straight toward Akko we laid our course, conveying with us to our people new knowledge and many worthy wolfskins!

No more need I tell of our increasing trade of far-flung sails. Phœnicia was growing in prosperity as never land had grown before. Yatnan had become Phœnician and we worked its copper mines, and had a temple in its city, Paphos; the fame of Tyre and Sidon was extending throughout the lands of Egypt and the Euphrates, and our ships and caravans carried such wares as might tempt all peoples. As for we three, Aradnus, Malchus, and I, we were now among Phœnicia’s richest men. Of the rest, it appertains chiefly to me alone, and is not as I would have it!

Of Elissa, fairest of Paphian women, I have no complaint to make. The gods will judge her, but not the gods whose nostrils fed upon the sacrifice. There was none like unto her in all the Yatnan city, and we inclined to each other, and, after much earnest wooing, she became my wife. Proud I was and prouder still when she bore me a son, lusty and comely, who soon had twined his little fingers round my heartstrings and whom, after the way of doting fathers, I deemed the fairest child in all the world. They were golden days which followed, until I sailed away again upon a voyage—and then came Baal!

Of the religion of the Phœnicians I have not yet spoken, and only in rage or shame may one tell of its quality. Of its origin I know nothing save that the great Baal, or Moloch, as one with him, was as the creating and yet burning and destroying sun, and that he must have his worship and his sacrifices. Lightly was this religion held by such as I and the other sea-rovers, in whose faces blew the pure winds of the sea and who had seen and who knew of things beyond wild superstitions, but with the people of the cities and the fierce, unknowing rabble this was not so, and they were under the dominion of priests as bloody-minded and full of frenzy as the savage cannibal creatures who dwelt in distant places. At this time, too, the worship had grown up into an idolatry of the most wanton and abandoned character, and celebrations were made common, ending in wild lascivious orgies wherein men ceased to be men and women no longer women, and wherein, as a beginning, there was burnt great quantities of incense, and bulls and horses were sacrificed in honour of the god, and finally—the horror of it—little children were given to the flames!

The image of Moloch in the temple was a beastly human figure of metal, with a huge bull’s head and outreaching, receiving arms. In the grossly protruding belly of the monster was a door through which a fire was built within him, that children laid in his arms might roll thence into the red consuming furnace beneath! What strange madness of faith may have misled and impelled them in their superstition who may describe, but, incredible indeed, there were those who thus gave up their children willingly, even the first-born and the only one! If it cried, the mother would fondle and kiss the child—for the victim must not weep—and the pitiful sound would be drowned in the clamour of flutes and kettle-drums. Silent and unmoved must the mother stand, for if she wept or sobbed she lost the honour of the act and its reward, and the child was sacrificed, notwithstanding! Could there have been no other and stronger and more merciful gods, and where were they when such things came to pass? But of these horrors I must not take account. I avoided them, and we lived our happy life remote, my wife and child and I. I went to sea content, and eager only for swift trade and swift return. Scarce knew I even of the existence of Phalos, the dark-visaged high priest of Moloch.

How it came about it was fated I should never know, but I can dimly reason. Ever, since religion began, have the priests of every faith used woman, credulous, yielding, and fatuous, as the chief instrument for promotion of their sinister dominion. Gentle and faithful was my Elissa, but somewhat inclined to dreaminess and observing the prayers to the gods, though partaking in none of the rites of the fanatics. Most resolute she was, too, when a matter became fixed in her mind, though to me she always yielded. Yet in the body of this fair and gentle creature might lie, ready for distorted moulding, the soul of a new zealot, deadly and sacrificing. Alas for me!

Most profitable had been my voyage, the winds were with me on the return, and I was full of the joy of the thought of the welcome which awaited me, when, one afternoon, a sail showed far in our front and swiftly nearing us, which I soon recognized as that of Marinus, captain and trader like myself and one of my closest and most sturdy friends. Soon he made signals that we should check our course, and then was rowed aboard us. His aspect was black and ominous.

“Strain every sail!” was all he said when first he spoke.

Then came the hideous story! How or when he knew not, but my wife had passed under the grim spell of the priesthood, especially under that of Phalos, the high priest, a man overbearing and ruthless and ambitious. Counting on my absence, and of the force which might be raised to face me and my allies on my return, my only one, the man-child of my heart, was to be made a sacrifice to Moloch on the morrow, and so the too truculent and irreligious captains be taught, through me, a needed lesson! Swiftly as he might, Marinus, trusty friend, had put to sea to warn me, and now he would sail back with me to aid me in what might come.

I answered not. I could but grasp his hand. At last my voice came and then but broke forth in a bellow to spread every sail and man every oar and drive forward the ship as never ship was driven before! How they sprang to do my will! What look of deadly import came upon the faces of Malchus and Aradnus! Marinus departed for his own ship, to follow in our course.

What sudden freedom and happiness must not madness sometimes bring! How good to change, relieved from agony of mind, into unknowing, babbling forgetfulness! But no kindly madness came to me in those long hours when the ship, though so forced upon her way that Marinus was left behind, yet seemed to me to only creep along the hindering waves. So passed the long night; sullenly through it all I could hold converse with none, though my companions would comfort me in my affliction and so sought, in vain. With morning the wind still held us, and with mid-afternoon we entered the harbour of fair Paphos. Even as we swung inward a boat darted forth from the land bringing a messenger from another of the captains—for my vessel had been awaited by my friends as Marinus had arranged. Then fell the blow! Now, even now, the rites in the great temple were in progress and my child about to be offered as the sacrifice!

Then, with need so ghastly, the better gods gave back my reasoning strength. We would invade the temple and would make a rescue, if it were within the power of man. I took swift and stern command anew. I would lead with Malchus and Aradnus next and a portion of my crew as well, the others remaining to hold the ship in instant readiness for sailing. It was the counsel of the wise Aradnus that, should the child be saved, we should sail at once for Egypt, where were a host of friends, and where priests of Baal had sometimes been flayed alive. I looked upon my brown-faced crew and knew that I could trust them, even the sun-burnt galley slaves. How many times had all these ranged dangerously beside me in times of struggle with the savages! I took from my weapon chest a certain Assyrian axe I cherished, short-hafted but broad and keen of edge and heavy. I kissed the axe and laid it against my cheek and then thrust it in the bosom of my tunic. We landed swiftly and rushed toward the temple. Vast was the throng about the structure, and inside I knew must be as dense, save for the great open space before the place of sacrifice. Wedge-shaped we struck the heaving mass and drove through it as wild boars through reeds, straight past the entrance, even to the inner circle of the mad worshippers, and, as I leaped clear of them, my eyes were smitten with the whole dread picture! There, before the altar and the beastly red-heated image of the leering god, side by side stood Elissa and Phalos, the grim high priest, he stern in his power so manifested, she proud and erect as she passed my child into his waiting hands. How a blasting picture can transform a man!

In all the world of living men there was not another then so strong as I; in all the wastes and desert places of the vast forests there was not a wild beast more ferocious; in all the earth or in the heavens above there was no being with more swift and certain mission! I bounded across the space between us, leaping to Phalos even as he took the child and was about to face the grinning idol, and then, as he turned at my hoarse shout and our eyes met glaringly, I drove that Assyrian axe down through that head, down through that crafty brain, down sheer between the hating eyes, and, as I caught the child, he fell crumplingly as any poled bull of one of his own sacrifices! I saw but as an instant’s vision Elissa sink to earth in a white swoon, and bounded with my child toward the entrance where the fray was raging, while about and behind me rose first the groan and then the yell of vengeance of the frenzied worshippers. Naught for the moment checked me with my circling axe seeking more blood. I reached nearly to my followers, so near to Aradnus that I tossed the child to him over the intervening heads and had the joy of seeing him, upon my shout, bound away with it toward our vessel and so preserve its safety. Nearer and nearer to my own men I struggled, but I could not reach them. The fierce guards of the priest were all about me now and a thousand of the mob were crowding savagely behind them. I felt a spear thrust in my side, and then another, and so went down most happily. My man-child would become a man in Egypt!