CHAPTER XIV

ALESIA AND THE END

That there had been a sea fight was plain from the look of the deck, upon which blood was splashed about and gathered in some places into little pools, now turned to a dark purple in the sunlight which was shining down upon it pleasantly enough. Pleasant also was the breeze which was carrying the galley westward without any aid of man in the guiding. Of the fight itself, it seemed as if I could remember something, though but confusedly, for first it would appear that we were battling among trees or in open ground, and then again that we were thrusting and striking and grappling up and down a tossing and slippery deck and that hoarse shouting was mingled with the roar of a great wind. Now, there was neither much wind nor any shouting. I lay with my head upon some sort of a not uneasy pillow and looked upward into a sky without a cloud. I felt a stiffness in my limbs and there was inertness to me. I made shift to rise to my knees and at last to my feet, and looked about me weakly, and considered. Yes, assuredly, there had been a sea fight. My pillow, the quality of which I had not noted, showed that, for it had been old Regner, now lying motionless, who had borne my head upon his bosom while I lay senseless. A huge spear, which had entered at the shoulder, protruded from his side, and he had bled much, lying there transfixed so savagely. I found that I had wounds myself and that there was a great bruise on my temple which still somewhat affected me.

Slowly, as the wind blew coolly on my forehead, came back to me a knowledge of what had been our evil fortune and how it was that I, a man of some presence among our daring company, I, a Viking of the Angles, should be drifting thus wounded and alone in mine own ship, helpless to guide it. The crafty Romans had outwitted us and we had not been spared!

In our fast shield ship, not a very great one but swift upon its way, we had been lying in wait, as was our custom, in a small bay of the Gallic coast, awaiting the near passing of any vessel which seemed to offer booty. What came, we cared not greatly, for we feared no enemy we might encounter, though preferring much some laden Phœnician trader still venturing to Britain. In default of such rare prize we must content ourselves with a chance ship of the Veneti, who also had some traffic beyond the narrow sea.

Proud were we Vikings, for was not ours the blood of the bold races of the forest who had swept up the Elbe five hundred years ago and, dividing into kindred tribes, Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, had seized upon all Jutland and, from hunters and river fishers, had become most bold and skilful sailors and the most adventurous of rovers of the sea? Already there came dread to the dwellers at the riversides and all along the Gallic coast and, sometimes, even to the shores of Britain, when our shield ships showed their sails against the distant sky. No ship of the Gaul we feared, but we sought not acquaintance with the now frequent Roman galleys, since they were prone to come in squadrons. Ever we kept a lookout for them and cared not when they appeared if only there were space enough between us, for we could outsail them easily. This was not so much because we feared, as because there would be but little spoil to follow the taking of a ship containing only legionaries, and there was the further reason that, were we ourselves to be taken, we would die at once. To the Roman, and it must be said to most others, we were but ravening pirates, ruthless and dangerous as the sharks of the sea or the wolves of the land, and meriting only death. Little cared we! We had but inherited the ways of our ancestors from the time when they raided the lands, each of the other, in the German wood or seized upon the holdings which seemed good to them as they fought their way northward from the branched sources of the Elbe and Weser. Yet we were never cruel, and lacked not loyalty and faithfulness unto death to friend and blood kin.

We were not as yet a great force, we rovers of the sea, though each year our strength increased. Our sharp-prowed ships were swifter than those of others, our sails bore better, and our arms were stronger at the oars in failing winds, but as either clan or tribe we, as yet, made no great war. We were but bold adventurers, each captain fighting for himself and his own following. Of religion we knew but Odin and the strong gods with him. It was so among each tribe of us, the Jutes above us on the great horn of land called Jutland, we Angles next and the Saxons below and nearer the restless peoples of the vast forest. The Romans knew us not apart and called all us Northmen, Saxons, though we were not as one in our scant rulership, and sometimes had our battles over marks. But we were of the same proud blood and did not fight with each other when there could be found a common enemy, such as existed now, since the conquering and oppressing Cæsar had, in a great sea fight, overcome the fleet of the Veneti, who were traders and had more ships than any other Gallic tribe. Afterward the victor had built more ships of his own and landed in Britain and done much damage, besides exacting submission and hostages from those nearest the coast. After this there still remained a number of the Roman ships which sailed about the coast of Gaul but did not come into the northern sea. These we avoided though we still made forays along the Gallic shores, having no other place for profitable venture. With this Cæsar, we of the upper coast beyond the Rhine had made no war, nor had he made war on us, deeming us but barbarians of a land not worth the conquering and of a kind only to be done away with, if it might be, when his ships encountered ours and which had happened but few times, since, as I have said, we avoided all such meeting. Yet now, I knew as my memory came back, that we had indeed been tricked and had mingled most bloodily with these same Romans.

We had been rejoiced when, from a point of land beside a little bay we had discovered, just as a black storm threatened, a ship nearing us which, as the manner of its building showed, must be a trader of the Veneti, having broad sails of skin, such as the Veneti used, and high prows and lifted stern and showing a structure broad and deep and strong. We were at first surprised, but considered then that Cæsar was no longer harrying the coasts of the Veneti and that, since conquering them and afterward causing the death of many, he had allowed those remaining to engage in all their avocations as before. So we thought it was possible that their traders were venturing forth again. Of this we were more assured as the ship neared us and we saw upon its deck only the sailors needed for its handling in the increasing tumult of wind and sea. These wore the Veneti dress and we could scarce restrain our shouting. There would be little of good fighting, but much plunder.

There were only some thirty of us in our shield ship, for, as I have told, it was not a large one, but our arms were strong and ready at the oars, and despite the thundering sky and now high rolling waves, we swept out from the bay and fairly athwart the course of the oncoming vessel before its people appeared to see us. Then there were loud cries from them and a swift rushing about to change their course, though all too late. Swiftly we circled in beside them and cast up our grappling hooks and, shouting our hoarse war cry, poured over the unprotected bulwarks and upon the deck, there to hew down or take captive the weak Veneti crew. Death rose to greet us!

Leaping to their feet, shouting the Roman battle cry, a full hundred armed legionaries who had lain concealed upon that treacherous deck—even as our feet touched wood—were upon us with cast javelins and spear and sword. We were lost in the mass of them, each one of us surrounded and defending himself against too many. It was a bloody fight for but a little time, and only that the storm waxed fiercer and all footing was uncertain, we would have all been slain the sooner. There was no quarter to be hoped for. I felt sharp wounds before I reached the deck, and sprang backward against the bulwark that I might face the onrush to better vantage. They came in upon me so swiftly and so closely that I slew two with my axe and then I felt a spear point lightly, and sprang apart from it and upward, clutching, as I leaped, the ropes slanting from mast to side, and so stood with my feet upon the bulwark, holding with one hand to the cordage and smiting downward with my axe once more. I turned to our ship and, even as I turned, it was lifted upward to me by the raging sea, then outward, and I heard the grappling hooks tear harshly away through the oak rail. And in that swift moment, even as I leaped, a stone cast by a slinger struck my head and at once I knew no more.

And now, after how many hours I could not tell, I stood clinging to the mast that I might keep my feet and making study of the body of stark Regner. He alone had been left on guard aboard our ship when we cast the grappling hooks, and it was easy to see that he had been slain by a spear thrown vengefully from above, as was revealed in the manner of his transfixion. Surely slight suffering had come to Regner, and little had he felt the shock when I had come down upon him, and the storm tore our ship away from our enemies and hid us in the bosom of its darkness. Certainly bold and careless, though very silent, sailors had been we two as the waves tossed us, and my wonder was that we were yet aboard and the ship afloat unharmed. It was well built and strong, however, and no sail had been up when we made our attack, and so, somehow, and by sheerest fortune, it had floated until the storm subsided and we were now riding on smooth waters. And now I looked all round and away upon the sea more searchingly. To the westward I perceived a dim uplifting, darker than the hue of the water, and, as the breeze carried the ship forward, this dimness became more solid and it was made plain that it was land. Well did I comprehend its meaning. I, alone and wounded and in one of the hated Viking ships, was drifting helplessly upon the shore of Britain. My death, it might be, had been delayed for only a little time, but what of that? Death was the Viking’s brother. A weakness was coming upon me and I slid downward to the deck and slept.

When I awakened something of my strength had come back to me, though not that of a strong man, for my head had been hurt most evilly. Yet now I could rise by the mast again and look more calmly and resolutely upon the land I was approaching and which now rose clearly to my sight, and not more than an hour’s passage, at the rate the vessel was now drifting.

Now it chanced that I knew more than a little of this strange isle of Britain. For years I had been in almost daily speech with a British slave named Locrin, now an old man and under my protection. He had been captured long ago when fishing with companions in one of their curious open coracles of skin, or currachs as they were sometimes called, and had in time become almost an Angle, for he had been treated kindly under the roof tree of my own family and clan. Him I had, as I grew in years, been accustomed to take with me in my hunting, and sometimes on expeditions, and from him had I learned not only the manner of life of the Britons, how they fought their enemies, the raiding Caledonians which sometimes came from the north, and other like things, and had also gained from him some knowledge of his language. This I had used with him in sport, with the idle thought that it might some day become of use to me in my adventures. He had become a most faithful thrall and I, in turn, had learned to hold him somewhat closely. It was ever said of the Briton that as a clansman he was most loyal to his chieftain. Glad was I now, in a somewhat sombre way, that I knew something of this wild isle toward which I was being carried and of the people whom I must meet. How I might be received I could but guess, yet I knew well that it would most likely be as the wild beast caught prowling. Slight reason had the Britons to welcome with extended arms the Viking stranger. Who welcomes the plunderer, even though the plunderer be shorn of strength, and helpless? Assuredly, my thoughts were gloomy as I drifted.

Very slowly lapped the waves against the galley’s prow, and the wind which carried it ahead seemed to adjust itself most nicely to its doubtful mission. I stood with my back still against the mast, as needs I must, and saw nearing me each moment a prospect which was not unpleasing in itself. Fair were the Kentish shores of which old Locrin had often told me, and fair her woods, whatever of danger for me might lie concealed within them. The shore itself was a bright sandy beach up which the gentle surge rolled far, and beyond that was a stretch of sward and bush soon lost in a wood as dense and green and heavy as I had ever looked upon. Of human beings there were none in sight nor was there any other sign of life, though far away in the forest I could discern the rise of smoke. What might that forest hold, I dimly thought, to fix my fate or fortune?

The tide seemed with the wind, and my sailless ship was nearing the shore so steadily that soon it must ground itself upon the pleasant beach in water so shallow doubtless that I might make shift to wade ashore, if strong enough. Still stood I leaning against the mast and scanning the long wood narrowly. Then, suddenly, my gaze was fixed.

From around a point where the forest extended far down toward the beach, swung into view a chariot such as I had never seen, its galloping horses deftly driven by a swart skin-clad man wearing a sort of helmet and what appeared to be a breastplate. Behind him, resting one hand upon his shoulder and swaying easily with the chariot’s movements, stood the stateliest and fairest woman my eyes had ever rested on. Behind the chariot followed, running close and easily as if accustomed to it, some score of guardsmen, a few with shields and spears, the rest all armed with bows. So, for a moment’s space they came, then saw the ship and made instant halt, the horses pulled backward on their haunches and the whole company closing up at once about the chariot. What marvel that these Britons swerved? A Viking ship upon their very shore!

The company did not flee, but stood and looked, the woman still in her place and gazing long, with one hand raised above her eyes to aid the scrutiny. Some time she studied, then seemingly gave an order, and the chariot was driven forward, though more slowly now and followed by its company. My ship had come, by this, close to the land and must find ground in a moment, which it did just as the Britons drew up opposite and not more than a spear’s length or two away. They looked upon me silently, the woman, upon whom the others seemed to wait, most curiously and gravely. At last she spoke, and her words were brief enough: “Viking, what do you here?”

Glad was I then that from old Locrin I had gained some knowledge of the Briton tongue and could make some little shift at speaking it, albeit most stutteringly, for now it might stand me in some saving stead. What should I answer?

A little I paused and debated in my mind and then, looking into the clear and questioning eyes of that proud woman in the chariot, I did not hesitate nor falter. Stammeringly and haltingly, I told my tale as best I could in the strange tongue, with bold and simple truthfulness, concealing nothing. I told of my own name and standing and of the foray and the sea fight and of all that might concern my captors. The men stood listening with mouths agape, though with stern and threatening faces, but the fair countenance of the woman did not alter. I knew that she was passing judgment. At last she spoke again, slowly and thoughtfully:

“Viking and wolves are much the same to Britons, but it may be that your tale is true, and it is not without merit in you that you have fought the Roman. Other than I must pass upon your fate.”

Then, turning to her people, she commanded that I and the body of dead Regner be brought to shore, which the spearmen did, supporting me, who found myself still weak, and laying the body of my comrade upon the sand. Then, without further parley, and under direction of the woman, the band returned the way whence it had come, I walking with a supporting spearman on either side. We reached the point from which the company had first appeared and there came upon a roadway leading into the forest. Upon this roadway we travelled it may be half a league when we reached a crossroad, and there we came to a halt.

“Take him to where the king is sitting,” said the woman then, to those about me, “and say to King Cadwallon that I will follow swiftly, that I may make all clear to him relating to the prisoner.”

Then she looked upon me fixedly, but saying nothing, as I also looked upon her most steadfastly and as I had never before looked upon the face or into the eyes of woman. There came to me a marvellous understanding.

There were, among the race of Vikings, poets who made the Sagas and had gifts in the divination of what was most fair and noble and beyond all common things or hopes or fears, and from one of these had come the curious and lofty affirmation that it might happen, though most rarely in the world, that a man and woman should for the first time look upon each other and that there should come to each the vast knowledge that they two were but as one in a loving which could not be in any way withstood or denied, calling for any sacrifice. And so it was! Well I know it to be unbelievable, but, as we stood there thus, she a haughty princess of the haughty Iceni, as I came to know, and I, a Viking haughty as she, but rude and rough of port and now blood-stained and grimy, the truth of the thing so strange came out like light between us. Each knew it well and each accepted it unfalteringly, for we were made of such a mould. No loftier or more courageous was I in my degree than my fair and stately Goneril. We spoke no word, but, as we parted at the crossroad and her chariot swept away, I knew that beyond all doubting I should find her with King Cadwallon and that she would have already spoken.

Two days we travelled through the land of Kent, and each day brought me greater wisdom. Let none say that the country of the Britons is but a vast waste of forest, moor and fen, peopled only by wild beasts and tribes of men almost as wild as they. So had I thought it and so had those on the mainland, deeming only that along the island’s coast there might exist among the natives a variance from the barbaric and outlandish customs of the interior. On this same winding journey—for we sought the easier ways and made no haste—I saw herds of feeding cattle and droves of horses, and meadows and reaped fields, and many a rude but goodly homestead. Never had my eyes met fairer prospect than that on which they rested in this region lately ravished by the Roman, and I wondered not that its people had defended it as fiercely as they had vainly. My bent was all with them. My guard of ten sturdy spearmen, somewhat glum in the beginning, became amenable upon the way, and from their leader, himself a Kentish spearman and having some little wisdom, I learned that which gave me cause for wonder and hard reflection. We were marching through a bruised and smarting region, one where the souls of men were seething in unavailing rage and bitter protest. Cæsar had come and gone. He had not advanced far into the country but he had slain many of the islanders and ravaged the fields and, having driven the Britons into their forest fastnesses, had forced from their chieftains a promise of submission, and had taken hostages away with him. No harm had the Britons done the Romans before this harsh invasion. Little they knew of Roman intrigues and ambitions, nor of this Cæsar’s wars and conquests. They were content to live alone in their own way upon their own green island. Yet to them, unheeding and unsuspecting, had come this scourge, without a pretext. There seemed no recourse and no vengeance for them. They had been smitten, and their hostages were with the Roman army. What wonder that there smouldered in the breasts of these hurt islanders such hatred and such fear as may not be described! All this I gained from what the Kentish spearman told, and it was not in me to feel unlike the islanders. Truly they had sufficient cause for hatred of the Romans!

I asked the spearman concerning Cadwallon, the king, and learned still more. He, it seemed, was not the king in straight descent, but because King Lud, who had reigned before him, had left only children as heirs, he had come into power as regent, seemingly, but really as king in fact. Cadwallon, as the Britons called him, and as I also shall, though he was called Cassivelaunus by the Romans, was not altogether a bad king, but was held somewhat weak at times and he had, besides, certain enemies among the more envious and ambitious of the chiefs beneath him. Fortunately, the invasion of Cæsar had not reached his capital on the river called the Thames, and he was still secure in power. This capital was a place called London by its people and by all other Britons, though the Romans had named it Trinovantum, and was the town of chief importance in the land, having existed long and, being a port, reached from the sea and drawing the trade of the Veneti as well as, sometimes, of the far-trading Phœnicians who came to the southwest, the Cassiterides, for tin, and who sometimes extended their bartering voyages up the coast. Much pride had the Britons in their town of London, of which the legend ran among their Druid priests—some of whom were learned—that it was founded in the dim past by a Trojan chieftain who, fleeing after the fall of ancient Troy, had sailed with his people even to distant Britain and, after overcoming a race of giants living there, had builded this town beside the Thames and named it Troy Novant. This tale, however, I hold to be a fable. The Druids were ever liars.

From this man, too, I learned much concerning the stately lady of whom I was the captive, and who had given order as to my disposal. She was the great Lady Goneril, he said, a princess of the Iceni and kinswoman of King Cadwallon. There had been trouble among the Iceni as to the succession, and at this time the family opposed to that of Goneril was somewhat in the ascendancy and it were better in many ways that the princess should seek refuge, for the time at least, at the court of her kinsman. An aunt she had also, wife of a chieftain of Kent with whom she was but now a guest. Only brave words had the man of Kent for the fair princess, and, even now, my heart went out to him because of it. Most imperious of mood she sometimes was, he said, and of great influence with both the king and her uncle in Kent, but ever generous and just, and much beloved of all, from chieftain down to churl, Iceni though she might be. All of this much delighted me and gave pride. Most curious, yet just and due it is, that a man should cherish, even as his own, the honour and fame of the one woman to him.

On the morning of the third day we had news of King Cadwallon that he was hunting with a company of his nobles and attendants in a forest not very far southwestward of his capital, and to this place we took our course, the Kentish man who led being well acquainted with the region and all its devious wood-paths. It was not long before we neared the forest where the hunt was, a region where the guide told me were many stags and not a few of the brown bear, and soon we came upon parties of the huntsmen, who gazed upon me curiously but who did not molest us but gave instruction as to where to look for the king. It was mid-afternoon when we came to where he had paused for rest and meat after the long chase of the morning.

There were many tents pitched in a pleasant glade in the midst of the forest, one of them a pavilion larger than the others, and this was the king’s. We were halted by guards with spears scattered in a ring about the brief camping place, who, after our leader had told his mission, sent one with him to the king’s tent, and kept the remainder of us with them. It was not long before the Kentish man returned and said that I was to go with him at once. He took me to the guard at the door of the great tent, and by this guard I was taken within and so before the king.

There were a goodly company assembled there of chiefs and nobles and fair and stately ladies who had taken their dinner with the king and now were moving around and talking together, but who, as I was brought in, ceased in their conversation and looked upon me with much interest, from which I judged that my story was already known to them—as indeed it proved to be. I stood now before King Cadwallon, and there took note of what manner of man he was. It seemed the Kentish man had told me of him well. He was of manly height and framed like a good warrior, but his face was somewhat drawn and the look in his eyes was not of one who felt his power supreme. Richly garbed he was and grave and stately of demeanour, yet lacked his eye the eagle flash. Naught have I to say against this King Cadwallon, naught, though it came to pass that I knew him well indeed and never did his friendship fail me, but I could have wished him to be of a front more confident and even arrogant, since he had about him such wild and untamed lords and chiefs of clans. I shall not disapprove Cadwallon.

The king addressed me gravely, saying that already he somewhat understood my story, and asked me that I tell it to him with more fulness, as affecting, it might be, his own decision in the matter of his course toward me. I must perforce obey, and so related to him more completely than to the Lady Goneril all circumstances of the voyage which brought me such evil fortune, ending with what I thought a not unwise addition to the effect that we Vikings had no war with Britons and had never sailed against them.

To all I said Cadwallon listened most patiently and, it seemed to me, almost with approbation. He answered that it was very true that we had not forayed in Britain and had done no harm at any time, save it might be that some reckless ones had captured a few currachs of the fishermen who ventured too far at sea, for which no grudge was held against us, and he added, what was to me most heartening and promising, that we were kindred in spirit, while not of blood, in hatred of the Roman and that, at this time, we were counted, not as enemies, but as allies in whatever of war was likely to come to either of us. Then he spoke still further to me, who had of a sudden become most emboldened and at ease, saying that, having known of me from Lady Goneril and of my degree in my own land, he had it in mind to deal with me as one of rank and one having knowledge of the sea and ships and also of the Romans, and so to offer me service with him, with such command as might be later determined.

Here was sudden change of fortune surely for a shipless man and prisoner in a strange land! At first I knew not what reply to make; then as it came upon me how many of my friends were slain and how bereft I was of all things while here was opportunity for adventure which might lead to important happenings, I was inclined to accept the service, though still I hesitated, for a Norseman is ever a Norseman utterly. Then rose before me the face of a woman standing in a chariot, to whom I had given a great wordless pledge, and I paused no longer! I swore to give good service to the king and, raising me from my bent knee, he declared me one among his chieftains and bade me join the nobles about and make new friends, with one to aid me who was waiting. Then turned I and looked again into the eyes of Goneril!

Most prideful and stately seemed the lady, yet, in her dark beauty, there was laughter in her eyes as she took me by the hand and led me among the company, making me known to many of them and saying, as she laughed, that the king had accorded me her thrall, since she had taken me prisoner. I was, she said, to lead her little company to her uncle’s hold, there to acquire a better knowledge of Britain speech and Britain forests and ways of fighting, until I should be called to closer service by Cadwallon. I was well received by most, though some were silent, and I saw among the company of nobles not a few who seemed to have in them the stuff of hardy fighting men, though not of such breed as were in Jutland. Some slight acquaintance made I, but there was little time—besides, my mind was much on Goneril.

Next morning, with a slender train, we set out on our way through Kent. Only a rune-maker should tell of that too short journey through the Kentish woods and winding pathways. It is not in me to give a sense of its sweet flavour. Not many words we said at first, but we did not need them. We only knew—we two, each proud and close of heart—but knew as others might not know it, yet the trees knew it, and the birds and squirrels in the trees knew, and the horses upon which we rode. Only the men who followed us could fail to know!

We came upon the evening of the second day to the hold of Gerguint, who had married Bera, the aunt of Goneril, where we were received as became the princess’ rank, and where I was accorded as pleasing welcome, for a messenger had arrived ahead of us to tell of my degree.

Of Gerguint, whom the Romans later called Carvilius, I must now speak freely, as soon he proved himself to me, and of him I cannot speak too well. A strong prince of a strong fourth among the Kentishmen, he was one after my own heart, fearing nothing and having that understanding which makes one of high blood know of and recognize that which may be in another. It was in his mind to be to me as a close friend, and so he was from the beginning, hunting with me and showing to me all the differences there were between the Viking and the British ways, both in the chase and in the modes of warfare. Much he delighted to go forth with me in my Viking ship, which had been brought along the coast and drawn into a twining small river entering his lands, from which place we made short voyages along the coast. The Britains were not worthy as sailors and this was soon perceived by Gerguint, who now desired that they should build them better vessels, learning the things which would serve greatly for their own defense, and this he sought to bring to the attention of the king. So he and I became good friends.

And for Goneril and myself what shall I say? It is hard for a man to tell properly, so that it may be at all conceived or understood, of what is between him and the woman whose breath has become his own. No difference made it with us that the blending and welding had been so swift and unaccountable. It was a fate met willingly and, even when the time for words of mine had come, few were demanded. I sought to tell, in my unfashioned mode, of what was in my heart, and she but smiled upon me and told me that I need not speak. What days were ours as we rode the glowing Kentish woods in the late autumn and she told me of her people’s ways and sought to make me comprehend them, and of the boundaries and friendships and animosities of the many tribes and clans, and all else that might tend to make me fitted for some rule among them.

And what strange half history and legends had those islanders! Of these dim tales my Goneril told me many, and in a few there must have been some truth, as of the great king, Belinus, who had even invaded Gaul and conquered there. His sword was hidden, it was said, in the heart of a mighty oak tree, but none knew where the oak stood, unless it might be held among the Druid mysteries. And many another story and tradition of the Britons she related, not less curious. She knew the Gallic tongue and something of this she gave to me.

Even their art of war she taught me, and therein made me marvel. In her full veins pulsed only warrior blood and made itself so manifest that it seemed wondrous that in the same warm current ran all of tenderest womanhood and faithfulness. Indeed she was herself a warrior bold enough. Well do I bear in mind the first time she took me with her out upon the sands to teach me chariot driving, and how in the essay I swayed and tottered, guiding the horses bunglingly as we rushed along, her chariot in the lead, circling or overtopping and descending the steep dunes, or darting upward from the beach, to swerve and rock along a hillside. Never in any storm at sea had I such strain to keep my feet beneath me, though in time I gained the needed reckless skill, to Goneril’s vast approbation. Most solicitous had she been that I should excel in this, for the chariot was much relied upon in all the battles of the islanders. In fight, the warrior had with him a charioteer who drove against the enemy while the warrior, standing beside him, fought with javelin or spear or axe, or other weapon, as the ranks were neared or broken. When the mêlée became most furious the warrior, leaping from his place, would then engage on foot, the charioteer withdrawing from the fray a little to be in readiness in case of swift retreat or further charge on a massed body. Most formidable were these chariots, though only when they were afforded ground for evolution. In the close forest battles they were useless.

Winter came, sharp and keen and not unpleasant in this land of Britain with its climate tempered by a great sea current from the southwest, and, almost before it had begun, came my first service to King Cadwallon. There had come an uprising of a certain tribe whose overweening and ambitious chief sought, with the alliances he had made, to cast off the king’s authority. Gerguint was summoned to attend with a force, which I was to accompany, which body was joined to others, and soon we met the rebels in the northwest forests. It was not a long campaign, but there were sharp skirmishes and, finally, a battle which was one of merit and wherein I had opportunity for the dealing of Viking blows when much they counted. It chanced, too, that I had occasion to save the life of Gerguint, who had risked it foolishly, charging ahead among the savage clansmen and going down beneath a mass of them. Hard it was to hew a way to him and lift him to his feet again before they added other and more deadly spear-thrusts to the ones he had received, but I was well repaid. There came occasion for such gluttonous fighting, to shield ourselves until our own warriors reached us, as might have gorged a Baresark. Thor! but it was good cleaving! Back to back we stood, and I could ask no better shield than Gerguint. Fairly beholden proved he when the encounter ended with the night and the death of him who had been rebellious, and closer yet we became in comradeship. We swore blood-brotherhood, a thing which was excellent for me and later came to serve me in good stead. The return to London came, and there the king, to whom something had been related of my way in battle, had good words for me and made promise of some honour.

And why delay the story of what was the crowning of my desire and great and overmastering resolve? I asked that Goneril be made my wife, she proudly joining, and Gerguint did not fail me nor did the Lady Bera, for I had become as of the family. Then was the King Cadwallon sought, and, for a time, he hesitated. Counting all, I was but an adventurous stranger and of altogether alien blood. Yet, since that blood was noble and since I had sworn him fealty and had proved myself in battle, and, it may be, also because he felt the need of each strong arm, and, above all, because of the firm words of Gerguint, he at last gave his consent and had grace to give it finely.

There was a great attendance of the Kentish chieftains in the hall of Gerguint and of many from the court, and there was our marriage, and ceremonies by the Druids—whose former power, as well as the length of some few of them, had been curtailed by good King Lud—and abundant feasting and drinking and music by the harpists; and so we two, thus joined before all, found happily what life may hold. The winter passed, and spring came, and in the bursting of stream and bud and song of bird there was not more warmth and glory than in ours. So passed the days. Then, as the summer neared, a pall fell on the land!

It was in the air, a vague unrest and dread. There was no frolicking beneath the moon in any of the scattered hamlets; the labourer in the field looked often toward the wood; the hunter moved with senses more alert; the wild beasts themselves one thought were seeking deeper harbourage; it was as if all nature were afraid; the very winds seemed whispering repeatedly, in fear, the one word—“Cæsar!”

The alarm had come across the sea from the Veneti. A little vessel of that friendly people had eluded the Roman ships patrolling the Gallic shores, and so reached Britain with news of recent movements of the devastator. He had, it seemed, been engaged in suppressing a revolt of the Treviri, who lay somewhere near the Rhine, but, meanwhile, had given orders that a great number of ships should be made in readiness for his army at a port called Itius, lying nearest to the shores of Britain. That he had it in mind to once more make a descent upon the islanders was, so the Veneti messengers declared, a thing assured. It was this fell news which had sped through Britain and had aroused the sudden dread of which I have already spoken. What time the scathe might come no man could tell.

But if there were trembling throughout Britain there came also the courage which goes with desperation. Feuds were forgotten, as were boundaries, and there ensued wide summoning and a gathering of the many princes to consider swiftly what might be done in the impending struggle with the invader. It was agreed that Cadwallon as the chief among the southeastern rulers of the island, and in sort an overlord of some, should have the supreme command, and then the warriors came from every part, ranging themselves under their own leaders and forming, at last, a great force of charioteers and archers and spearmen and hosts of the wild skin-clad forest men, an army numerous as the leaves, but all in bands and with little discipline or order. So in and about the southern hills the great force hung. Then, one day, at noontime, there showed across the sea a mighty spread of sail. Cæsar would strike!

Eight hundred sail! What scores of thousands of the trained legionaries must they carry and what chance had an unordered host in an encounter on open even ground? It was decided by the leaders not to give battle at the shore, where the nature of the beach gave easy landing to the Romans, but rather to meet them on the high places, which had been fortified in a rude way by the felling of many trees in front of them. Here we awaited the attack.

Of that first desperate struggle against the veteran foe I can tell but vaguely, for I was in its midst, fighting as for my life and unseeing as to the general battle. Fiercely we charged and drove among the enemy with our chariots, but could not shatter them. These were the trained slayers of the world, and when one rank wavered or was broken, another rose behind it and ever the whole pressed forward, killing as it came and irresistible against a force with no planned manner of cohesion. We were driven backward, though fighting stubbornly, and, finally, the enemy overwhelmed and seized the camp, and the Britons, leaving a host of dead, were driven into the forests. There was a kind of re-formation and then began the running fight of days, as Cæsar neared the capital. There were bloody stands and skirmishes and we cut off many of the Romans in the woods, but nothing could stay their firm advance.

My Goneril was in London, where I had thought her most secure in this time of great jeopardy, though stubbornly she had insisted on following me into the field. Gerguint had joined his brother Kentish princes, and together they had attacked the Roman camp left with the ships and had been beaten, and there had Gerguint been sorely wounded and, barely escaping, had been carried to the harbourage of his castle. The main body of the Britons was now within and about London, and Cadwallon was to make his last stand against the approaching army of Cæsar, which threatened the passage of a ford above the city. At this ford all must be decided.

There had been treachery. Mandubratius, crafty and wavering chief of the Trohantes, to save himself, had cast his lot with Cæsar. Androgeus, a chief in command in London itself, had turned against Cadwallon and was tampering with the conqueror; and all these things gave fear. Yet we would make such stand as should be remembered long, and so all Cadwallon’s forces were drawn up beside the ford to dispute its passage. The Romans came, their legions rolling to the shore and entering the waters boldly while our own massed armament stood awaiting them with eager weapons, a multitude looking upon us from the slope behind, even our women among them, as was the Briton’s way. Then came the clash and struggle.

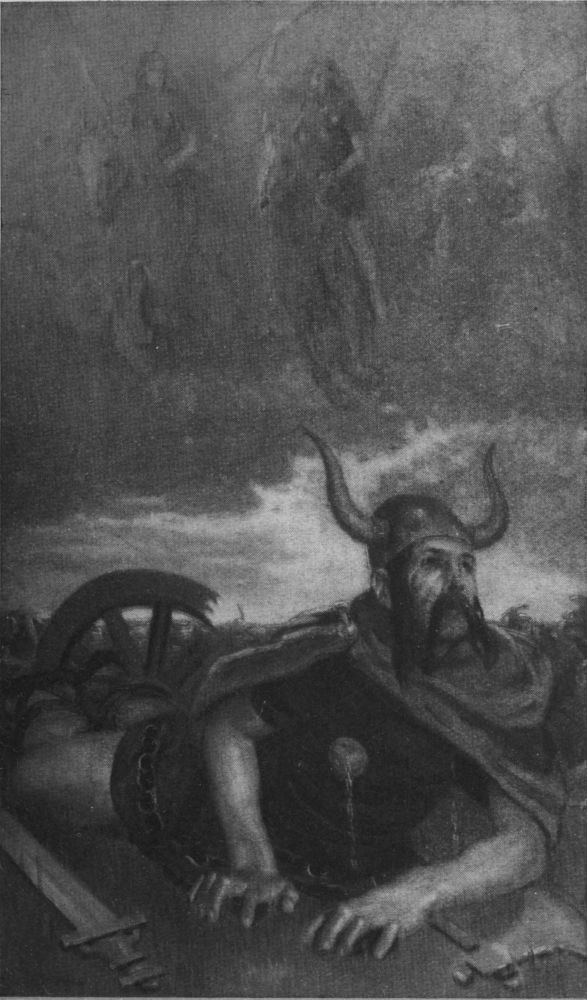

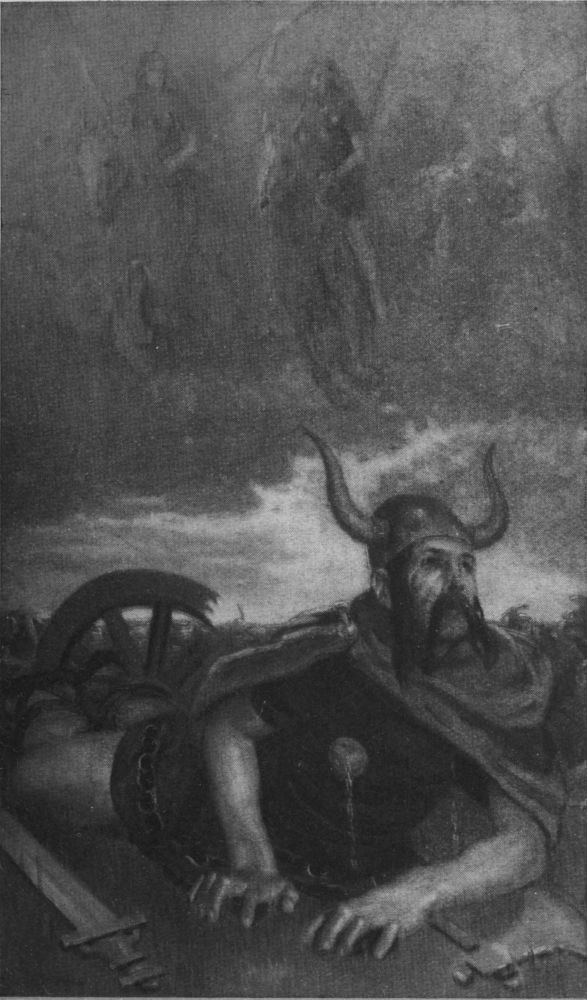

As the Romans neared the land, avoiding as best they could the sharpened stakes which had been set against them, their onrush was almost hidden by the cloud of spears and arrows falling upon them, and many were slain and carried downward by the glad current of the British river, but there was no checking them. Some struggled through and others followed as the first were slain, and soon the ranks had gained a footing, their front being lopped off as it came, but ever heaved forward by the tremendous mass behind. As in the surges of a growing storm, each succeeding wave crept further up the shore and the fight was soon on land. Though hate is in my heart for them, let none speak lightly of the dauntless courage or the stern hardihood and discipline of the Roman soldiers. Those ranks of iron pressed forward, though we raged among them with our chariots and met them manfully on foot with blows as fierce as their own and thrusts as deadly. But what could avail such ragged and open charge as made the wild Britons against an advancing wall which ever renewed itself as it was broken here and there? I, myself, fought side by side with chieftains of the Iceni, kinsmen of Goneril, with whom I had made friendship, and well they bore themselves. High up the slope were the Romans now, and there was at the front much intermingling of the opposing forces. My charioteer had fallen, and the horses had been slain, and I, on foot, was making red my heavy Viking battle-axe, but in dire peril, for we were driven backward step by step and soon I was half surrounded and felt a wound or two and began to breathe too heavily. Then came to my ears a woman’s cry. Circling downward and at one side from the slope above where were the onlooking multitude, had come Goneril, driven by grizzled Leir, her charioteer, and swinging to the front and very centre where she knew I would be found. There had been none who could restrain her. Mad with her fear for me, wild as a she-bear for her bayed mate, she had come storming on the battlefield, her dark hair streaming and the love flame in her eyes, seeking only to be with me, even in death together. And timely was her coming, for I had been beaten to my knee and was in sore strait. Surely the gods guided, for the chariot came to me through the mêlée as the wild bull through brush, and I was lifted to it by Leir’s strong arm as, scarcely slacking in its course, it passed athwart the raging lines and so away toward safety. And, even at that moment, as Goneril bent down toward me tenderly, there came a Roman javelin which drove deep into her side and, as it lurched out and away with the chariot’s surge, left, following it, a rush of her dear heart’s blood, drenching her robe with red. Into my arms she sank, and so I held her until, flying, we reached the wood, then laid her gently down on the greensward.

“I am weakening and dying. The Valkyrie are circling in the sky”

What can I say of that awful, awaiting moment, or of what came? She was still alive, my glorious Briton girl. She smiled upon me and sought to reach up her arms about my neck, and could not; then sighed a little and there died! Then all things passed away, and I fell as dead beside her.

There is little more to tell of Britain. Cæsar had triumphed; London had fallen; the conqueror had wreaked his stern will upon the land; Cadwallon had yielded and had agreed to pay tribute, and Cæsar, taking hostages and many prisoners to be sold as slaves in Roman marts, had sailed away. For a hard four hundred years the Roman heel would press on Britain’s neck. What was all this now to me! They had carried me and my dead Goneril away into the forest and, joined by certain of her kinsmen who had escaped, we took up our journey with my dead to the country of the Iceni, where they would bury her with the ceremonies befitting such a princess. All this we did, but I could speak no word. Men looked upon me with a sort of fear. My speech seemed lost, but came at last with the new swelling of the heart and the humming of the dark thoughts in my head. Nothing of Britain knew I longer. I was a Viking again with only Viking gods and Viking thoughts, and these transformed me. Cæsar had slain my Briton girl and, though it were forced or proffered, all the weregild of all the Roman world could bring no solace. Goneril was dead, and henceforth I lived but to bring death such as I might to every Roman! No oath of vengeance needed I to take on the white holy stone of Odin’s priests. I sought Gerguint, still wounded in his castle, and was received as if the castle was my own, but abode there only as a silent and unheeding guest. Time passed and, finally, I sought the little band of those I had hardened and taught to sail my shield-ship, and they joined me nothing loth, and in the darkness of a stormy night we crossed to the coast of Gaul, where I would fight against the Romans, for secret word came that there was nearing a head a vast uprising to cast off the Roman yoke.

Far to the south and west we laid our course, for I would hold it so well out at sea that we might avoid the Roman ships now haunting all the Gallic coast. Some days we sailed and, at last, having escaped them, made entrance at the mouth of a fair river called the Seine and sailed inland upon it until we reached an island where was a town, the capital of a partly maritime and trading people, the Parisii, who, because of their lack of strength, had allied themselves with the Senones, a more powerful tribe lying to the south of them. In this capital of the Parisii, or Paris, though called Lutetia by the Romans, were many who understood the Briton tongue; my small possession of Gallic also aided us somewhat and we were received with willingness and provided with food and a place for harbourage. The scene about us was of utmost tumult.

It was winter now and all Gaul was aflame with the hope of casting off the Roman power, in which great enterprise the various tribes had, after a council, ranged themselves under the leadership of Vercingetorix, a noble of the Arverni, and than of whom they could not have made wiser choice or one more likely to be followed by great outcome. Not only was he a man of courage and much skill in warfare, but also one who thought, not for himself alone, but calmly for the general good. Already had he a strong army in the field and was, after some slight successes, seeking to check the advance of Cæsar upon Avaricum, the chief city of the Biturges, and one which should have been abandoned. Vercingetorix had pleaded with the Biturges that they should sacrifice it for the sake of the whole country, that it might not fall into the hands of the Romans and so give them stores and shelter until they might carry on the invasion to better advantage when spring should come. In this he was overruled or overpersuaded by his assembled leaders, for the Gauls had some of the weaknesses of the Britons, in that they were most difficult to control as a united body. So Cæsar was advancing, though but slowly, upon the city, and Vercingetorix was hanging near him with his forces, making sudden attacks upon his flanks and withdrawing swiftly and with much display of wise generalship as the need came. To Vercingetorix, then, came I at once, followed by my little handful of adventurous Britons who were most faithful and men of hardihood, for such I had selected for my shield-ship.

In this journey I attached myself to a small force led by one Critognatus, an Arvernian of note, who had come to Lutetia to encourage in the uprising and was now on his way to rejoin the Gallic army. Him I found a man of firmness of mind and of a fierce and unbounded patriotism, and he it was who promised to bring me personally to Vercingetorix.

Through many a devious forest path, across many a silent stream and over wide frozen marshes, we took our way and reached the Gallic camp on the evening of the third day. It made an amazing and curious sight, with its far extending fires beneath the trees of the dense wood lighting the ways between hosts of rude shelters of boughs or sods or tents of skins until the lights but twinkled in the distance, for it was a huge force which had now gathered. Through a long way I was guided by Critognatus to see that I had audience. The tent of Vercingetorix stood near the centre of the camp and was somewhat larger than the others and had sentries at its door. I was taken within by Critognatus and my name and mission told to Vercingetorix, but I need have had no sponsor.

Most cordial was my greeting, though of a certain dignity, for Vercingetorix was one of a commanding and grave air, albeit his eyes gleamed brightly. There proved occasion for little speech. Of all that had occurred in Britain this wise leader had made himself acquainted and it so chanced that he knew my story well, and well could understand what impulse drove me now and what manner of service I might give. He placed me with the command of Critognatus, and, upon my asking, directed him to allow me, under my own leadership, a company of some hundred of a wild outlying clan of the Arverni, with whom I might adventure in my own way. Glad was I then!

What days and nights of brooding came to me! Ever I saw the tomb of Goneril or the fanes of my own gods! No puling gods of the weak races they, but war gods and gods of vengeance! Wild and savage and unfearing was my band of an outlandish mountain group to whom I had joined my few of Britons, and whom I now trained to more knowing warfare, but even they were scarcely equal to the fierceness and persistence of their leader. No venturing foragers from the Roman camp were safe from our ambushes or sudden onslaught, for I hovered like a wolf about a fold, and many a legionary’s blood made the snow brighter in my eyes. There came to me something of a name, and I was made welcome among the Gallic chieftains, stately in their glittering helmets and tunics and rich furs, and some of them most gallant men and good, but I could not be as One with them. I held myself aloof in a stern loneliness. They were not of me or mine. What says the Norsemen’s rune:

“Gasps and gapes

When to the sea he comes

The eagle over old ocean;

So is a man

Who among many comes

And has no advocates.”

But little recked I of it all. I only sought and slew with my hardened following. Then, later, fell Avaricum, and Cæsar, his army fed and rested, turned toward Vercingetorix, who, after some well fought but unavailing battles, entrenched himself in the city of Alesia, where he awaited the issues. Alesia was a town of the Mandubii and one well fortified and of importance, founded anciently, it was related, as a trading-place of the Phœnicians. It lay upon the flat crest of a great hill, almost a mountain, and was protected on two sides by the rivers Lutosa and Osera. In the front the mountain sloped down into a plain a league in width, behind which, at some distance, rose other hills which surrounded the plain completely. The army of Vercingetorix now occupied the wide slope of the city’s hill down to the plain and had made before it a long deep trench and a stone wall the height of a man throughout. Upon the plain and nearer the hills were arrayed the Romans, who began at once a gigantic work of encircling fortifications such as I had never seen before and which gave me new comprehension of the utter inflexibility and hungry and all-conquering resolve of this great Cæsar. None other could have devised so vast a plan, and by no other army than his could it be executed. The inner circuit of this enclosing zone was a full ten miles in length and, gigantic as was the work, there was built in front of it a trench twenty feet in depth and of the same width, and, within this and nearer the fortifications, two other trenches each fifteen feet deep and wide, and filled with water let in from the river. All this was as a hindrance and protection against any sudden sally by the Gauls, of whom there were with Vercingetorix some hundred thousand. Not only this, but, at a distance and in the rear of Cæsar’s army, was erected another and longer line of defense against the Gauls elsewhere, who were rallying in great numbers to come to Vercingetorix’s assistance. I had somewhere heard a strange tale of a huge serpent which had coiled its vast length around an Afric village and engulfed the starving groups as they came forth in desperation, and the thought came to me again with this coiling of the awaiting serpent, Cæsar.

There were sharp conflicts as the work progressed, for we made frequent sallies from our wall, and there was one fight of the cavalry which caused great loss on both sides and might have ended still more hardly for the Romans had not Cæsar sent to their aid a great force of the Germans who were with him, and who fought solidly and well together. Much it enraged me to behold these Germans, for they were somewhat of the same blood as my own.

Still grew the Roman fortifications and the whole thing was marvellous. Each Roman soldier, it seemed, was trained to every sort of labour and accustomed to it as to the march or battlefield. The army was made up of legions, containing from three thousand to six thousand men; the legion was divided into ten cohorts, the cohort into three maniples, and the maniple into two centuries, and each moved as if a part of one great being. Never before was army a machine so deadly, propelling itself in whole or in its smallest part as guided by a single mind. What Briton or Gallic force, however great, could cope with this!

And now came anxious days to Vercingetorix. The promised succour was delayed, and famine threatened. It was resolved to send away the helpless people of the Mandubii, but they could not pass the Romans. Very early in the siege Vercingetorix had fairly divided, man by man, all corn and cattle and other food, and this was near its end. A council of the leaders was now held at which was to be considered the best course to be taken, and at this council Critognatus spoke most eloquently, counselling a sally and a swift determining of the great issue, however fatal. Then came the news by messengers who had passed the enemy that our allies had come and that, under the leadership of Commius, they were about to attack the Romans in great force!

There was no faltering now! We must sally forth when our allies made their attack. The assault soon came, and for two days there were fierce charge and countercharge and much slaughter, the Gauls outside assailing the farther Roman works as did we the inner ones. On the fourth day came the bloody climax.

There was at the extremity of the Romans’ northern line a hill which could not easily be included in their works, and the outer Gauls had perceived this hill’s advantage. They took from their main army sixty thousand of their best men, and these, under command of Vergasillaunus, passed round and seized the hill at night. At noon, it was decided, this great force should make its charge. Then all would join the battle and all knew that, before the night fell, there would come an end either of free Gaul or of the dreadful Cæsar!

My axe was red with Roman blood. My arm was wearied and my body sore that night, and through the brief hours of rest I snatched I slept but fitfully. That my sleep would fail me in the night to come I had no fear, for I knew in my heart what must befall. It did not daunt me. What warrior had done better? What says the Havamal of Odin:

“Cattle die,

Kindred die,

We ourselves also die;

But the fair fame

Never dies

Of one who deserves it!”

At noon the battle burst with utmost fury, as Vergasillaunus hurled his force upon the Romans and, almost at the same time, we from within assailed the ramparts. Nothing could stay us. The ditches were filled with clay and hurdles, the walls were mounted, their defenders slain, the turrets cleared, and we burst fairly through the breached wall and struck our foes on even ground. What foaming struggle then, what vengeance sought for wrongs, what strokes for freedom! Should victory come to him, what mercy would he show, this harsh and treacherous Cæsar! Even I, who fought for my own hand and for my vengeance, could not but feel hate with the Gauls. For this man surely the gods must have a punishment. The noble Vercingetorix may grace his triumph, to be later murdered in a Roman dungeon; each Roman soldier may boast a Gallic slave; a servile populace may greet the conqueror madly, but certainly the evil day and evil end must come. May the daggers of false friends some time await him!

We raged ahead and slew, but ever came swinging into support the Roman legions in the way I knew so well from Britain. And no longer could we force them. Oh, for a thousand of my wild Jutlanders, Angle, Saxon, or Jute, I cared not, to hew a way with me into those solid ranks! There came a sudden rush and so close a press about me that I had not room for the swinging of my wet axe. The Roman short sword is most keen and, driven into a man’s side and cleanly through him, he must reach the earth. The feet of a host of charging legionaries passed over and beyond me, and there came to my ears their distant shout of triumph.

The blood is flowing from my side and I am weakening and dying. The Valkyrie are circling in the sky. It is the end. How will they appear to me and how receive me, Odin, the all-father; Thor, the hammerer; Balder, the beautiful, and Freyja and all the great queens and warriors of the past? That must be as it may be. I have fought well. And now even the gods are lost in mist. Strange visions are coming to me, visions of shining seas and the vast ocean, of warm, palm-clad lands and lands of ice and snow, of plains and forests and the dark mountain passes, of a thousand fierce encounters and of other and more gentle things. Above and beyond all, I see a creature, soft-furred of arm, dark-eyed and wild and beautiful of her kind, near to me in the lofty treetops and gazing at me gravely from between leaved branches!

THE END