CHAPTER VII

A LIGHT IN THE DARKNESS

I received Gerry’s more explicit congratulations in private. The poor little Professor continued to bemoan our desertion of the quest with such heart-breaking insistence, that the merest suspicion that it was no stern necessity that bade us sail north would, we felt sure, induce paroxysms of fury. We cheered him to the best of our ability, by picturing our early return refreshed for deeds of high emprise in rock climbing, and with perfected means for their accomplishment. But he continued to bewail himself.

It was about six days after we had turned our backs upon the great rock wall, that the wind began to get up strongly from the north, and we had to thrust our way slowly enough through the great surges that rolled down upon us mercilessly from the Atlantic, with four thousand miles of gathered impact at their back.

Our good little boat cleft her way through their white manes with a sturdy shove and shake of her prow, sending the spray swinging in jets before her cutwater, and flooding her decks as she dipped to the rollers and sent them roaring down beneath the bridge.

Two men had to be lashed to the wheel, and the crew took their stations between watch and watch, only by the activity with which they dodged the incoming billows. Two of our boats were swept from the davits, and half the deck-house windows were smashed before we got them battened over. The cook kept a fire in the galley by the display of the most extraordinary agility, and our meals were snappy and disconnected. Nor did we take much pleasure in them. Gerry and I had found our sealegs to a certain extent, but poor little Lessaution was a terrible sufferer, and we found it hard to take a neighborly interest in his behavior—he would insist in coming on deck, though he had to be lashed there—and afterwards find appetite for the cook’s hastily improvised dainties.

We had twenty-four hours of this sort of thing, and then it began to get monotonous. The wind dropped little by little, but the sea was nearly as high as ever, and the evening closed down upon us with our wretchedness still supreme, and the waves pervading everything from the cabins to the stoke-hole. We joined Eccles in the engine-room, where, if not dry, we were at least warm, and toasted our steaming clothes before the red glow of the furnaces, while we took exercise by bracing ourselves to avoid being dashed into the heart of the machinery by the great heaves and struggles of the fighting ship. It was a way of passing an evening which came with some originality and freshness to both Gerry and myself, and we stayed there late confabulating over our prospects, and wondering whether our attempt at an interview with our young women would be successful, and what sort of greeting we should receive.

“It’s all very well for you now,” said Gerry despondently, “you’re all right. You’ve got your title and an income, which might be worse by a long way, but where do I come in? I’m as badly off as ever. You’ll have to work your new-found influence pretty vigorously to get me any sort of billet to satisfy my ma-in-law.”

“That sort of thing’ll have to come later,” I answered. “Probably we shan’t get more than an hour with them, if that. Port Lewis isn’t such an enticing sort of place, from what I’ve heard, that the Madagascar’s likely to stay there long. They’ll just coal and that’s about all. But if Denvarre and his brother haven’t settled matters by now—which the Lord forbid!—I think it won’t do us any harm to remind our young women that we’re alive and still taking an interest in them. But with Denvarre for competitor I don’t see that you’re worse off than I am. Don’t let’s brood, though, old chap, but let what will betide. If our chances are gone from us completely, then we’ve got the best possible counter-irritant to depression handy. We can turn back and find our excitement still waiting for us at the foot of that stupendous wall.”

Gerry smiled hopefully, bending forward for a light for his pipe. A dreamy look crossed his face as he swayed apathetically to the roll of the ship, and as he rose and braced himself with his arm around a stanchion I could see that he was musing mistily over the future. I felt a little that way myself, and there was a silence between us for a time, broken only by the regular beat and clang as the great piston rods thrust themselves backwards and forwards, and the eccentrics jolted round clamorously.

Suddenly from the deck above came a hail, and Janson thrust his face, glistening with salt-foam flecks, into the disc of light where the man-hole gave upon the darkness.

“Light on the starboard bow, my lord,” he bellowed, to make himself heard above the jar of the machinery and the shriek of the storm. “The skipper thinks there must be a whaler afire.”

Gerry and I snatched at our oilskins, which we had doffed when we had descended from the sousings of the deck, and climbed the little iron ladder unsteadily. We were still ploughing our way into the trough of the head-sea, we found, when we gained the deck, but the great rollers did not come shooting over the bow and down the slippery planks as they had done an hour or two before. The sea was evidently going down, but was heavy enough yet to make us pity from the bottom of our hearts any poor wretches who had to battle with it in open boats.

Far away, very dimly and intermittently as we rose on the crest of wave after wave, a light flickered now and again away to starboard, shooting up occasionally into brightness as we and the burning craft stood out on the top of a sea together, lost utterly when both of us sank back into the trough between the seas, and evidently drifting towards us rapidly before the force of the northern gale.

I clambered up on to the bridge beside Waller, and bawled into his ear.

“Shall we be able to help,” I questioned stentoriously, “or is it too late?”

“Too late to do anything for her,” he shrieked back, shaking his dripping head, “but we ought to stand by for her boats, if they can live with them, poor wretches.”

The stress of conversation was too great to indulge in further. I grasped the rail before me and stood at Waller’s right hand, straining my eyes into the night. We needed all our strength, really, for the screw, but at Janson’s suggestion, the dynamo was set going, and our little searchlight streamed out in a thin shaft of light into the darkness. It tinged the frothy breakers with a dead white glow as of hoarfrost.

So we rode forward into the storm, the wind shrieking through our strained cordage, the spray fell like the lash of whips on our glistening decks, and the thud and swish of the surges against our bows answering the regular thump and rattle of the anchor-chains in the hawse-pipe, and the racket of the groaning machinery that echoed up from below.

Far ahead the little zone of golden light flashed before us, dancing and winking amid the tossing of the seas, darting here and there, pulsing quiveringly down the shaft of brightness that fed it from our top, flitting like some brilliant petrel of the night from crest to crest, spurning the foam, glittering through the veils of hissing spray that fell behind it like cascades of radiant jewels. And after it we waddled along steadily, fighting the rollers, flinching before the sting of the flipping drift, nosing into the depths of the green combs of angry water, rolling, pitching, jarring and quivering, but ever following like some trustworthy and attentive duck trailing after an evasive hummingbird.

The sheen of the furnace upon the sea was gleaming nearer. At times the glimmer of its flames was hid from us, as some mountain-like wall of water flung itself in between, but the glow of it was never lost to us. We could see the sparks stream up like puny rockets, as the gale planed them off the edge of the blaze, flinging them in clouds to leeward, as the ungoverned hulk swung heavily between the seas. The masts were pillars of living flame, that streamed into the night in bannerets of fire. Out of the main hatchway a solid white-hot glow of light was projected, shot with red streaks as burning splinters floated up in the strong sea-draught. From stem to stern the unfortunate bark was wrapped in a fiery sheet as the conflagration leaped and roared about it, devouring the seas that broke aboard into clouds of rosy steam.

“God help the poor wretches,” I shouted to Waller; “there’s no one left alive on that.”

“No, my lord, not this half-hour back. It’s their boats I’m watching for,” he answered, as, with the peak of his cap pressed over his eyes, he strained his gaze into the night. “It’s a ten to one chance against any boat living in this sea, but—well, there’s always a but, my lord.”

Janson was flirting the searchlight about and about the blazing hulk, like a very will-o’-the-wisp. It fled round it questioningly, picking at and dipping to every floating piece of wreckage, but never a one showed the sign of boat or human being. With our steam to help us, there was no danger in approaching the floating furnace as near as we thought well, and we slid up towards it as it lurched past us, till the heat of it blistered across the red seas on to our salt-cracked faces smartingly. The sparks skipped by us, and hissed like little adders on our streaming planks, but gaze as we would, nothing but charred timbers and leaping breakers met our eyes. We plunged forward into the darkness again, as she lumbered by before the wind.

“We ought to hang about in the direction she came from,” explained Waller thunderously. “The boats, if they lived, wouldn’t keep her pace. They aren’t so much exposed to the gale.”

I nodded, still gripping the rail before me, not wishing to waste breath that was twisted from one’s very lips by the wind, before it could frame a single intelligent word.

So we plodded on for a quarter of an hour or more, seeing nothing. I could but remember what agonies the unfortunate victims of this mischance must be suffering, if by any terrible hap they were swinging near us on those hungry seas, seeing help and safety at hand, and yet without a hope of rescue save by utter chance. And I thanked God for the wet deck below me that I had been cursing but a short hour back.

“I suppose the oil caught fire?” I asked Waller, as a slight lull gave one a chance to make oneself heard. “I shouldn’t have thought any ship could have flared like that in this sea.”

“She’s no whaler, my lord,” returned the skipper decidedly; “I can’t quite make out her build. More like a liner, only no liner would be down this far south. She had big engines, judging by her funnels. Looked for all the world like one of the old Black Cross Line.”

“The Black Cross Line!” I repeated wondering; “why, that’s a funny thing. Some friends of mine have gone cruising in one of their steamers round ——” and then the frightful horror of it took me by the throat, and I could have shrieked aloud. The Black Cross Line! The Madagascar was one of their boats, yacht-fitted for cruising. Oh! the thing was impossible. It was some coincidence that fate had raised up to frighten me. Waller just spoke in the haphazard way men do when they make comparisons. Of course, he had served on some vessel of the fleet, and his thoughts strayed back to it. And yet—and yet—no ordinary liner would be sailing these seas. And the Madagascar was expected in these latitudes. My God! it was a thing too wanton for even my luck to have conceived and brought about. No fate could be so devilish as to drag me out these weary thousands of miles to see my love’s agony of death in these desolate southern seas. No; no God that ruled the universe could allow it. I wrestled with the cold reason that insisted that these things could be, and that it was stretching the limits of mere coincidence to say they were not.

Into my tortures of despair a hail from Janson broke, and he swung the leaping flash-light from before our bow like a lightning streak. It streamed, a path of light across the billows, to port, and centered there on a tumbling, reeling object, buffeted by the bluster of the breakers, half hidden by the curtain of the spin-drift. Together Waller and I tore at the wheel, and slewed the ship towards it. Slowly, ever so languidly, the bows came round, and began to edge across to where the disc of light hovered unblinkingly. The dark object leaped up ever and anon, poised upon the dancing surge, only to drop back as if engulfed absolutely in the dark abyss behind the roll of the breaker. A white object fluttered, as we could see between these intermittent eclipses, streaming out against the yellow light glaringly. Round this, as we drew near, we could distinguish a huddle of misty outlines, animate or inanimate we could not tell.

We circled heavily to windward, and Waller roared his orders to the crew. The oil-bags were hung outboard, and as they dribbled lingeringly across the surface of the foam, the tossing died down as by magic. Half-a-dozen seamen clustered at the side, and with uplifted hands, swayed coils of rope above their heads. The engines slowed as the engine-room bells clanged, and we half stayed. Then with the blow of a great roller upon our lifting keel we staggered on again.

Still nearer we floundered, drifting broadside on, to the round yellow patch wherein the dim mass still danced uncertainly. Nearer still, and we hovered over it, reeling under the thunderous blows that the windward waves hammered upon us, and rolling nigh bulwarks under into the oily calm to leeward. Nearer again, and the ropes lashed out like whip-cords across the interval from the waiting crew, and were caught and hauled at desperately by the eager wretches aboard the pitching boat. Nearer now, almost under the churn of our wash, and the searchlight stared down unquivering into every crevice of its wild confusion, swathing each face in its glare. And white and set, silhouetted haggardly against the blackness of the outer night, the face of my love—my own dear love—looked up into my unbelieving eyes.

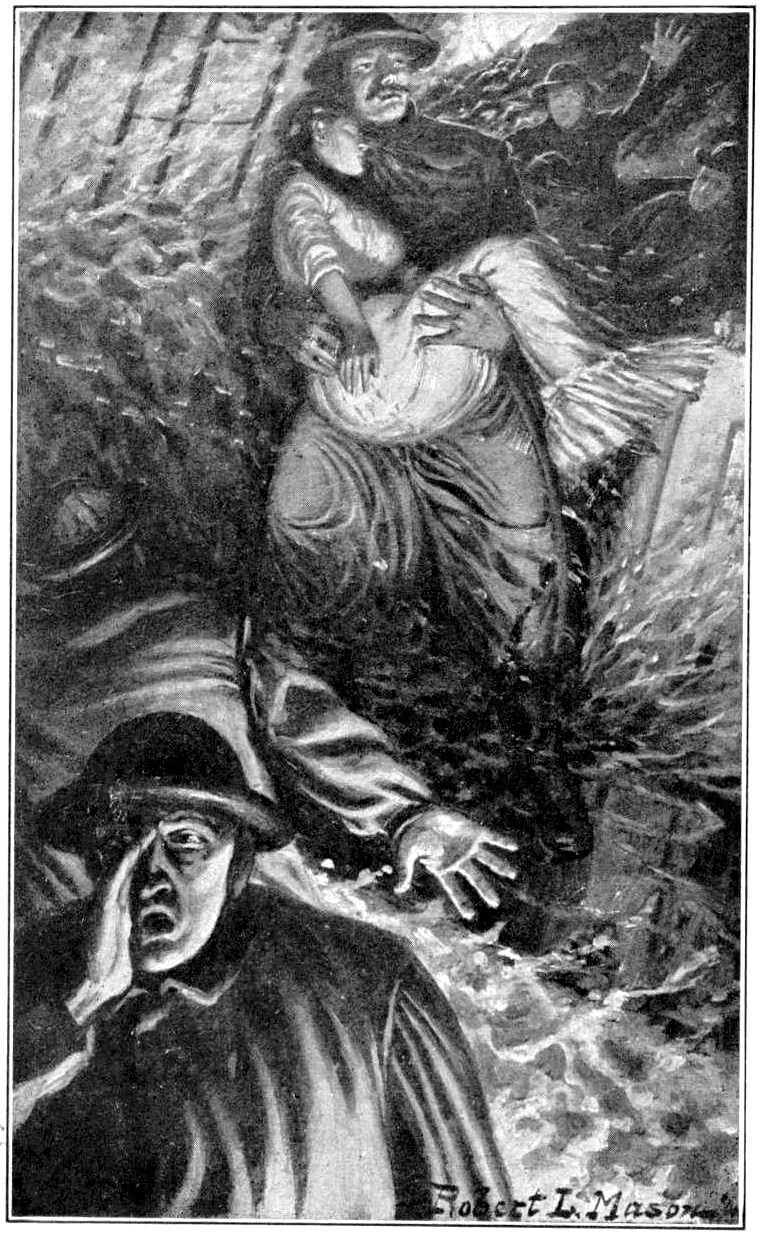

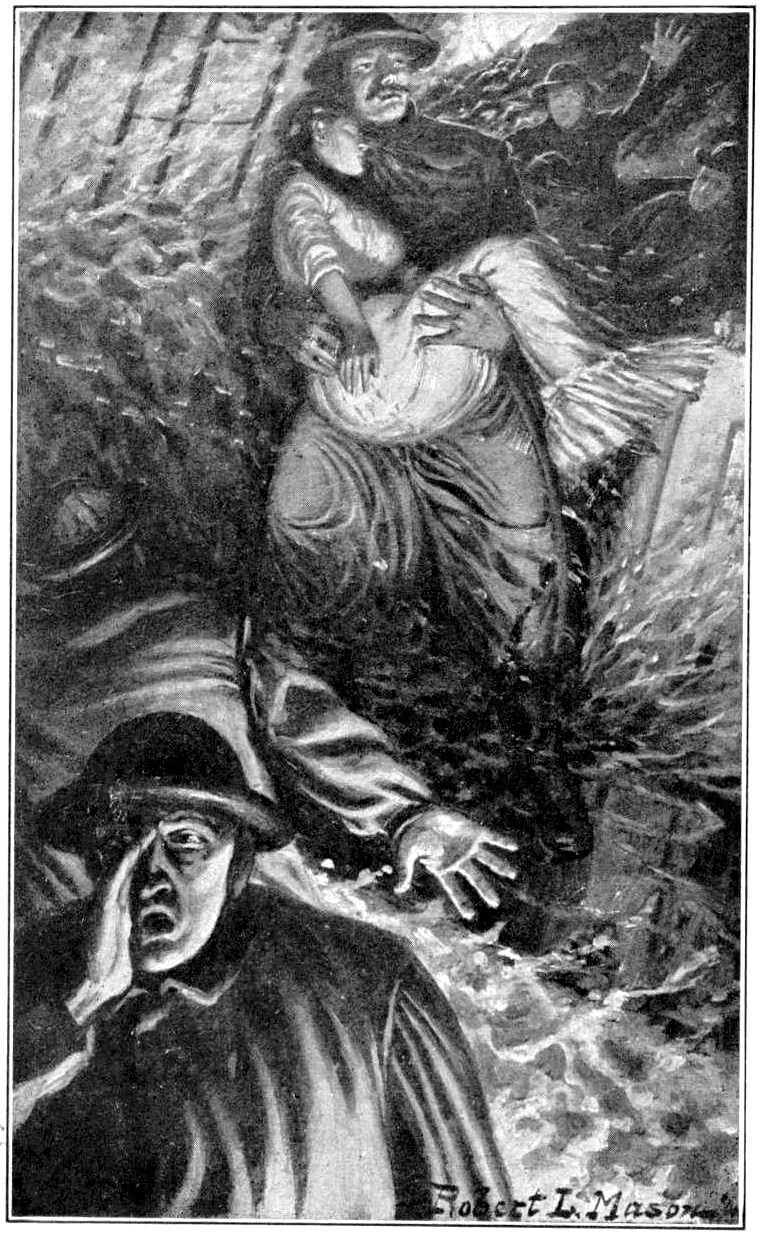

OUT ... OF THAT BLACK YEASTY WHIRLPOOL CAME MY LOVE.

I heard an exclamation from Waller as I flung myself from the wheel, and heard him grip his breath as he braced himself to meet the plunge of the ship alone. I was but human, and who was I to stand unmoved beside him there when the light of my eyes was swayed in the grasp of death before me? I took a leap on to the wet and slanting deck, and fell upon my hands, but rose beside the bulwark unhurt and panting. Then a hail from the boat reached across to us above the raving of the wind, and I saw our men tug frantically at a rope that tautened suddenly. A dark body came swiftly flying up to the bulwarks as the men hauled, and with eager hands we seized it, fending it from the jumping list of the timbers. A single glance showed me Lady Delahay’s face, sunken and shriveled with fifty new lines of haunting fear. Another hail, another strenuous pull, and Violet fell into the arms that Gerry held out to receive her. And then—ay, then, and till I go out into the eternal beyond, the memory of it will be vivid in my inmost soul—out of the swirl and uproar of that black, yeasty whirlpool came my love into my embrace, and lay upon my breast.

We bore them into the cabin, and poured cordials between their white lips. We chafed their frozen hands and fetched hot bricks from the engine-room to place beneath their feet. We tore off their outer garments—for ceremony flies through the porthole when death is knocking at the door and wrapped blankets round them and rubbed their limbs furiously. We did everything that men can do, of a good purpose but unhandily, to bring them back from the edge of the eternal sleep whereon they hovered, and soon—in the younger women’s case at least—with success. Then as their eyes opened, and the color began to creep back languidly into their cheeks, and they sat up in utter wonder at their surroundings, we left them, with every appliance we could furnish forth, to revive in her turn their mother, giving them but little explanation of their whereabouts, and being eyed by them with a surprise that we could but hope had pleasure at its back. But this was no time for sentimental musings, and we hurried on deck to see what had betided to the others.

Eight men had been hauled by main force from the tumbling boat, which had reeled more and more tempestuously as her living ballast lightened, and the last poor fellow, with no restraining hand on the far end of the line, had been bumped fearfully against the bulge of the hull as we rolled back. But bruises were the worst that any man had received, and we hustled them into the smoke-room unceremoniously.

Janson was still flinging the searchlight rays across the tumbling waste of water, but a word from one of the half-drowned mariners made us stay him.

“Not another two spars are afloat together of the other boats,” he gasped, as the blood began to flow again in his frozen veins. “Every one was matchwooded against the side as they left. Ours was carried off, half full by a wave that broke the painter, or I shouldn’t be here, and thank God for it.”

“How many aboard you?” I asked, shuddering to think what a toll the night had taken; “you’re the Madagascar, aren’t you?”

“Yes, we’re the Madagascar,” he answered slowly and with surprise, “though I don’t know how you know it, seeing you’ve let the boat drift. An hour ago she was the finest pleasure craft afloat, with a hundred and twenty passengers and fifty crew as jolly as could be. And now there’s us,” and he flung his hands out towards his fellows with a gesture of weak despair.

“An hour ago!” I demurred, “more than that, my man, surely. She could never have blazed up to a bon-fire like that in the time.”

“I tell you, sir,” he answered obstinately, “that less than an hour ago six score of happy men and women were feeding theirselves as contented as could be in her saloon. And now,” he added grimly, “they’re feeding the fishes. And in that boat for three-quarters of an hour we’ve been tossing over their dead, drowned carcasses, reckoning that every minute would see us join them. And Captain—my captain, what I’ve sailed with this ten years past—he’s down there among them, and I’m here, and ought to be thankin’ God, and I keep cursin’ every time I give myself leave to think. And that’s what comes of followin’ the sea, sir,” and he laid his rough, damp, grizzled head upon the table, and burst into a storm of hysterical tears.

The others were coming back to consciousness one by one. Baines touched me on the shoulder.

“There’s one here that won’t last long, my lord, I fear,” he said, leading me towards the other end of the saloon, where another limp body was stretched across the table. “We can’t bring him round at all.”

It came as no shock of surprise to recognize Denvarre’s face and drooping yellow moustache. His eyes were closed; his cheeks fell in limply against his jaws; the breath came in a thin wheezy hiss from between his white lips. He was in the last stages of cold and exhaustion. They tried in vain to force brandy between his set teeth. He had not the muscular power of swallowing left. It did indeed look as if Baines was right.

I won’t stop to tell you the thoughts that seethed and ran riot in my brain as I saw him fighting for his life with the cold that had nigh mastered his pulses. They belong to the category of devilish inspirations that come to a man when some wild battle with nature furnishes forth a throw back to pure animalism; when self is uttermost and honor unborn. They are monstrous phantasms of the brain too dark to materialize into wholesome words, and best forgotten save when the system needs a purge of shame. God forgive me my desires at that single moment—for a space of mere seconds saw me myself again.

Suffice it to say that with every aid we could devise we joined him in his wrestle with the death that was gripping him for the final throw. We fetched spirits, and rasped every part of his body with rough towels soaked in whisky. We smote with our palms upon his rigid limbs, and bent and kneaded his unyielding joints; we thrust heated bricks against his feet and hands; finally, at Janson’s suggestion, we collected handfuls of the sleet that was falling on the decks, and grated them furiously upon his skin. And at last the life began to flicker in him.

A tinge—faint and barely perceptible at first, but growing in strength—began to filter into his cheeks. A sigh burst from his throat and the tense lips parted. We tilted brandy drop by drop into his mouth, and heard his spluttering cough with joy. And then of his own effort he stirred and whispered faintly.

“Gwen?” he queried in a faint, far-away voice, and it was for me to answer him.

“Safe, and on board,” said I cheerily, as my heart sledge-hammered at my ribs, and my hands twitched to grasp his throat and tear the chords of speech away from him eternally. “Quite safe, old man, and coming round nicely.”

He smiled a happy, drowsy smile that stayed and slept upon his face as he wandered back into consciousness. And then I left him to his brother—who was among the rescued—and to Baines, and went stolidly up on deck, the fires of hell burning in my heart, and rage—the insane, unreasoning rage of disappointment—astir in my blood.

“Gwen, Gwen,” I repeated to myself, as I flung myself out into the gale that still slashed cuttingly down the deck. “Gwen she is to him, and, curse him, she’s Gwen no longer to me.”