CHAPTER XI

A GLACIER CAVE AND WHAT LAY THEREIN

An hour’s labor saw us well over the moraine, and beginning to worm our way into the deep clefts that gaped in the flanks of the hillside. Heretofore we had kept rigidly to the neighborhood of the shore, but now we had to shift our course inland. The mountain breasted up to the water’s edge sheer and inaccessible. We could see no possible chance of a break in its surface for miles.

There was nothing to do but cross the ridge before us, and take up our quest on the far side. If we found the way rough and dangerous, and deemed it impossible to carry over the sections of our cutter, we should have to return and recommence our quest along the eastern shores. But as far as we had gone there was nothing impracticable for men taking fair precautions and proceeding slowly, though at times the ground was steep and broken.

Before us a long, deep, shadowy gorge cut into the heart of the mountain. It led upward toward a narrow pass that dented into the crown of the ridge. This gave hope of a moderately easy passage to the other side. About half-a-mile in front of us the cañon narrowed, and the cliffs grew together, nearly overhanging in parts.

The going, however, was better. At times the path was as smooth as a paved street. Here and there enormous blocks of granite were ranged alongside it. They were curiously square, having almost the finished look of building material.

Gerry was the first to remark upon these things.

“There never was a better imitation of an Edinburgh street,” said he wearily. “These cobbles are as hard and even as can be.”

They certainly were set together in regular fashion, and we examined them inquisitively, wondering what geological freak had brought about their ordered formation. Lessaution clapped his hands and shouted.

“Aha, my friends, aha! What have you to say now? A boulevard, is it not? Who made this road, my little Iscariots? Did it make itself out of nothing? Did the stones roll themselves together? Tell me that, my braves,” and he grunted triumphantly, waggling his hands at the rows of measured blocks.

“I think,” said I irritably, “that any people who put them here with a set purpose must have been of a race of engineering idiots. What in the name of wonder could a road be doing here, leading to nowhere in particular out of this chaos? It’s simply a geological freak. Some stratum has slipped.”

“It is a road, I tell you,” shrieked the savant, “a road, a road, a road! It has been begun to fetch stones upon—this stone that we see ready cut for moving. Is it that you are blind? Can you not see?”

I had no wish to delay the expedition further while he lectured us on this supposititious discovery. I answered him patiently.

“My dear Professor,” said I, “let us agree that it is a grand staircase, or anything else you like to think it. But for goodness’ sake let us get on. What we are looking for is not a highway, but a beach—unless you would like to stay and investigate the matter by yourself,” I added hopefully.

He came along muttering many things. He was understood to say that some people had no more enthusiasm than a slug; that the British nation at large was utterly wanting in verve and spirituality; that in our poor company his intellect roamed desolate and companionless. But we regarded him not, striding upward till we reached the point where the cañon narrowed and darkened over us.

This defile continued for about a quarter of a mile, and along it still ran the curious effect as of a cobbled road. At the end of the neck we could see that the valley divided, one half continuing up the pass, the other striking away sharply to the right.

We reached the sharp spur of the mountain that hid the second valley from our sight. We rounded the corner, all five of us abreast. As a single man we stopped in our surprise.

Almost to our feet a mighty glacier rolled, clear, clean, and blue as the firmament, still and cold as the shadow of death. A gasp went up simultaneously from each throat as we stepped so swiftly and unknowingly into the presence of this mighty ice-river, standing out in such lonely whiteness and solemnity; for an appreciable moment no one spoke.

Then came a shrill yell from our irrepressible friend. He pointed up the side of the new valley, his little eyes fairly blazing in their sockets.

“There, there!” he howled, “as I told you, it is there. Name of all the names, let us climb,” and he scrabbled at the smooth rock face that fenced the entrance of the far cañon, plucking at it like a caged squirrel.

We followed the direction of his forefinger, and I will confess that my first feeling was one of desperate annoyance, for on the edge of the ice, standing out yellow-gray against the blue crevices, was something uncommonly like the wall of a ruined or half-finished building. Nothing could explain this away, and it seemed possible that Lessaution might have some ground for his fancies. Any wonder or interest I might have felt in this discovery was swallowed by the irritation I felt in remembering what scorn I had always thrown upon Gerry’s and Lessaution’s imaginings, which now might well prove to be borne out by facts. I gaped upon the phenomenon therefore distrustfully, as if it might be, perchance, a put-up hoax.

The Frenchman was still extended upon the ice-planed rocks, wriggling like a worm, but advancing not at all. Gerry seized one of his outstretched legs and gave him a lusty shove. The ungrateful little wretch never so much as offered him thanks or a tug in return. He gathered himself up, and tore across the confusion of the ice-milled stones like a lapwing.

Parsons respectfully offered a back, as at leap-frog. We took advantage of it to scale the tiny precipice, and follow in the savant’s tracks. The slow-blooded Mr. Parsons, after eyeing the unaided ascent that would be his if he pursued us, sat himself down beside the baggage, and lit his pipe with solemn content. The rest of us joined Lessaution beside the building, or whatever it might be.

It was supposedly the rear of a house, and ended with great abruptness where the glacier began. There was no roof, merely three stone walls built of excessively solid blocks—not natural, but evidently quarried—and at the glacier side it broke off suddenly, as if beaten down by some sudden shock. Inside the walls was nothing but a little heap of dust.

Lessaution ran round and round it and in and out of it like a monkey exploring a new cage. He chattered and swore away to himself, paying no sort of attention to our doings. It was left to Gerry to make the next discovery. He was standing gaping down into the crevasses of the glacier edge.

“Great Heavens!” he ejaculated suddenly. “Look here, you chaps.”

Ready for any further astonishment, we flocked to him greedily. He pointed to the unsullied sides of the ice-wall, and therein we saw a wonderful sight. Plain to the view, as if cased in a crystal casket, were more huge blocks of stone, the ice arching over them transparently. Most evidently they were the masonry that had formed the facade of this building, which the glacier must have in part destroyed. They had been swept down into a sort of bay or basin in the rock. In this hollow they were only covered by a shallow of the mighty river of ice, and it had rolled its slow current over them for centuries. But lying, as they did, beneath its sluggish current, they had remained flung up as in a sort of backwater, and free from injury. And here lay the wonder of the thing. For carved on these great monoliths were a hundred cabalistic figures in myriad combinations, every one, as we could clearly trace, formed of the same symbol that figured in my wonderful scroll.

When you are beaten, the grace of a neat surrender will turn tongues from your defeat. I went up to Lessaution with an outstretched hand and an ingratiating smile. He greeted me triumphantly, and with many joyous outcries, but I will say was handsome enough to forego all superior airs of patronage. He made no allusion to my previous scepticism.

I told myself that, in some ways, this discovery was a great misfortune as matters had now turned out. True enough, we had come here to investigate the possible remains of such a race as was now conclusively proved to have existed. Had matters gone as we intended we should have been gratified beyond measure at this result. But as circumstances were, the discovery of a suitable shore for launching our boat was preferable to all the antiquities south of the equator. I ventured on a modified résumé of these sentiments, but the Professor snapped at me like an angry parrakeet.

“What!” he exploded. “Shall we leave these fine and perfect palaces? Are we to desert them to search for a beach—a muddy bank of sand? No, it is not possible. Here we can delve into a buried past, and explore the relics of a royal race. I plant myself here, and Beelzebub shall not tear me from the spot. Under correction you must see as I do. A beach now—but that is absurd,” and he turned to his investigations, waving aside my suggestions superbly.

Gerry and Denvarre were a bit flushed and excited over the matter. The former opined that an hour or two’s pottering round these walls might be interesting, and that discoveries worth making might be made. He suggested that the mid-day halt for food should now take place, and that if necessary Lessaution should remain afterward while we strolled forward on our way. We could pick him up on our return.

I agreed to this compromise sulkily, and marched down to where Parsons still smoked patiently among the packs. He rose to his feet, and stood at attention.

“Put up the little cooking tent,” said I, “and light the little stove. We’re going to camp and lunch.”

He began to unfold the canvas and erect the shelter for our little oil oven. I busied myself in getting out the meat pie that Baines had provided, and extracting knives and forks from their various receptacles. Then I sat down upon a boulder and watched Parsons’ further operations with a dreamy content in mere idleness and in the sunshine.

“Wonderful pretty, that, m’lord,” said Parsons confidentially, as he looked up from his labors, crimson with much bending. He pointed with his finger toward the farthest side of the glacier, whence a stream rippled out patteringly.

I followed the direction of his hand and saw, what, in the general distraction of Lessaution’s first find, we had overlooked.

A huge ice-grotto, blue and delicately shaded, ran deeply into the heart of the glacier. The sun sparkled on the archway that spanned the entrance, glowing through panes of clear ice in fifty azure shades and glittering prisms. The stream that purred out, born of the friction on the granite bed below the ice, looked heartsome and inviting in the sunlight. It was in contrast to the stony immobility around, and I rose and took a few steps forward to contemplate it.

The cave ran straight back from its mouth into the ice-hollows, and the reflections lit it up for some little way back into its dark recesses. It looked mysteriously fascinating, as its blue shadows melted into the impenetrable gloom. I stepped a few yards into it, admiring the delicious tints that filtered through the roof. The thought struck me that while our lunch was warming it might be amusing to investigate this sub-glacial waterway. I returned to Mr. Parsons, who had watched my motion with genuine but repressed interest.

“Have we candles?” I inquired.

“I did happen to put in a couple of dips, m’lord, thinking they might come in useful if we camped the night. Not that we have what you’d call much night here,” added the sailor, as if it was an additional grievance of these outlandish realms.

He produced his greasy little parcel, and we entered the cavern, getting well dripped on by the way. The little cascades fell freely from the roof in the increasing heat of the sun.

As the gloom deepened we lit up, and I strode ahead holding my candle high in the air. Parsons followed behind, gaping. In this order we plunged into the icy mysteries before us.

The stream was a shallow one—not above four or five inches deep for the most part—and we splashed and slushed along with ease on its sandy bed. But the cold was atrocious. It struck home the deeper for our sudden withdrawal from the full sunlight. As we advanced the clear blue of the ice above the entrance deepened to a sickly green; as we went on to a lurid purple. Finally the rays ceased to percolate through the heavy masses above us. We were in thick darkness—the gloom that has never known the day.

I heard Parsons shiver behind me as he crept closer. The roof-drippings fell with a hollow splash in the pools and shallows. A fearsome stillness filled and pervaded the cave between these patterings. Our steps and splashings seemed to roar out with indecent echoes on the awesome quiet. A scene of impertinence—of pushing forwardness—in thus invading these awful recesses fell upon me. My steps began to slow; a shudder swept my nerves, making me tremble creepily.

As I slowed and halted I noticed that the drip and trickle from the roof had ceased. The cave was widening and deepening into a space that the feeble light of our candles refused to fill. We were in the midst of a growing emptiness.

I looked above me. The roof was lost in gloom. A thick, velvety blackness was over us, and no answering flash from ice walls came as I waved my light. We had strayed from under the glacier, and were overhung by some huge escarpment of the mountain-side. On the one side of us was the wall of ice; on the other the sullen gray cliff of granite. The floor was smooth. The stream oozed along the foot of the ice-wall with a silent, splashless flow.

We walked half aimlessly forward, hesitating for a direction in this uniform emptiness. Then the light passed uncertainly upon a yellowish mass a few fathoms before us—a vague breaking of the dimness of the void. We drew toward it, and the shadows danced and played upon clean-cut blocks; there was no mistaking their nature. They were quarried—the squared masonry of a buried city.

Parsons crept closer again.

“’Anged if it ain’t a ’ouse,” he whispered, and it seemed to me that I could hear the throb of his pulses in the stillness. “A bloomin’ ’ouse,” he repeated, with the evident desire to prove to himself that this was no delusive dream.

We both breathed hard as we continued staring at the yellow gable, watching the waverings of the dip-light across its stones. Emotions that varied only in degree filled our minds alike. We were, without any doubt, horribly afraid. For half a minute we stood unstirring. Then by a common and inquisitive impulse we advanced shoulder to shoulder to the doorway.

There was no door. A fungus-smelling pile of sodden pulp showed what might have been wood long centuries before. Beside the postern lay a metal bucket, dull and dirt-colored; opposite the doorway was an open hearth. The floor was inches deep in a curious, strong-smelling, fungoid litter. Among it lay half-a-dozen or more utensils, all of the same dull-colored metal. In the ingle nook was a stone seat.

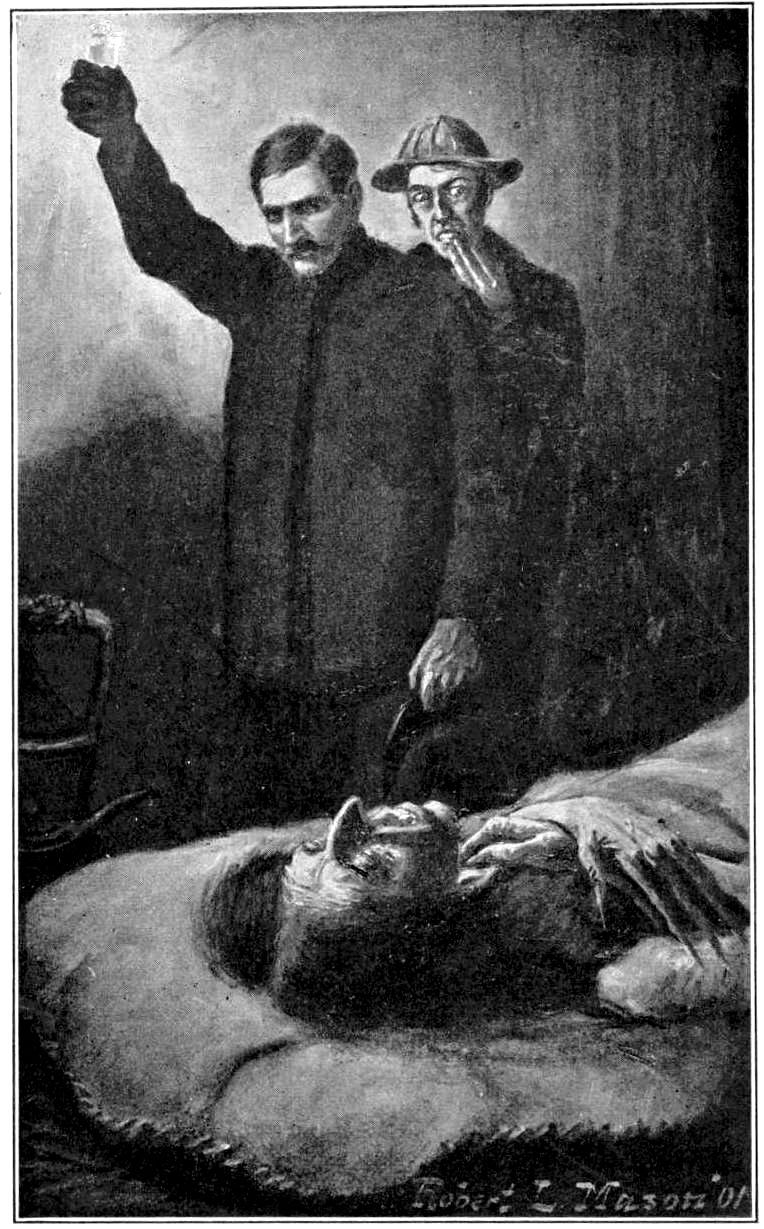

IT WAS THE FACE OF ONE ALONE WITH DEATH.

Another entrance gave upon an inner room. To this we strode delicately. At our entry we stayed our oncoming with a great gasp. I stepped back upon Parsons—shuffling and mowing at him unseeingly. My eyes were glued upon the far side of the room, while my feet with automatic intelligence endeavored to carry me out of it.

A stone slab filled the far side of this recess, and on it were heaped various sad-hued fabrics—bed coverings of sorts. They were discolored with age, but undecayed by reason of the undying frost. Above the tossed and furrowed ends of these rags a face appeared—a face lined with a thousand wrinkles, drawn and yellow as parchment. The features had been old and agonized or ever the breath left the body. They had been of noble outline in life, but terror had been laid like a thick mask upon the dead lineaments. It was the face of one alone with death—a death that crept to it slowly, while the soul waited in its desolation, helpless, alone, despairing.

Parsons found a cracked and reedy voice.

“Gawd pity ’im,” he mumbled, closing up to me fearfully; “’e ’ad it ’eavy at the last.”

The flicker of the wavering candle-light was chasing the gray shadows across and about the fear-haunted face. If was as if the agonies of centuries back had leaped to life. A drop from the roof fell upon the wick of a dip, making it hiss and sputter raggedly; the to and fro of the twittering rays made the dead lips twitch, as it seemed. The shade that swept the rigid form, as we moved toward it, gave it the horrid appearance of shuddering, and thereat I heard Parsons’ breath whistle between his teeth. The black hair fell lank and straight from the furrowed forehead, and as the thin light gleamed upon it, it seemed as if it waved in an unfelt draught.

We bent over the poor, distorted apology for a human form. The hands were crossed upon the wasted chest, each twined within the other convulsively. The eyes were half closed. The sheen of the dead pupils seemed to watch us furtively between the wrinkled lids. The lips were agape, and the teeth set stiffly upon each other. The muscles in the worn throat stood out like the kinks in the parcelling of a worn hawser. The whole face and figure gave the impression of despair personified—of death awaited lingeringly, and the bitter cup thereof drained to the last dregs.

There was a plash and gurgle from the stream behind me, and the swish of hasty stumblings through its pools. I was suddenly aware that I was alone before this gruesomeness—that down the watery pathway we had come Parsons was making for wholesome light and air at the top of his speed. He ran staggeringly, holding out his candle before him, and as I saw the outline of his body diminishingly black through the doorway, a cold dread caught me by the throat. Horror gripped my pulses clammily.

Somehow, within the next ten seconds, I found myself hunting Parsons hard down that icy waterway, with fright—pure, unadulterated funk—following desperately swift upon my footsteps. I stopped to consider nothing, save that behind me was the shadow of death centuries old in all its hoary malignancy, while in front was sunlight and nervous, warm-blooded humanity as personified by the escaping Parsons. With these considerations carven on my brain I splashed along like a hunted otter. Reeling, white-faced, shamed, but full of gratitude for the warm blessings of the sun and sea-borne air, we stumbled out into the cañon, and squatted again beside our baggage. We looked not each other in the eyes for the space of a full minute; then I gave a half-hysteric chuckle.

“It was only a mummy of sorts,” I explained apologetically to James Parsons, seaman and coward.

“That’s as mebbe, m’lord,” quoth Mr. Parsons with dogged deliberation, “but it ’appens to be the first I’ve seen of whatever it ’appens to be, an’ please the Lord I’ll never see another.” He capped this slightly involved indication of his views with a mighty spit into the clearness of the stream, the while he shifted his quid thankfully.

“Nonsense,” said I, with a great show of spirit and discipline, “you must come back with me at once. I dare say there are discoveries to be made of lots of things. Gold, very likely, and other valuables,” and I rolled my eyes at him. He only sniffed doubtfully.

“With all due respeck, m’lord,” answered the seaman firmly, “I would not go back if you dammed the brook with di’monds.”

“You’re a coward, Parsons,” said I disgustedly. “What’s there to be afraid of? It’s simply the body of a man who was caught by the glacier when it overwhelmed this valley, as it evidently has done. It’s the cold that’s kept him fresh.”

“Yes, m’lord,” answered Parsons, without conviction.

“So of course we ought to look into the matter further. Who knows what there may be besides what we’ve seen? I shall call the others.”

“Yes, m’lord,” quoth Mr. Parsons, with steadfast respect. “I should certainly call the others.”

I turned away, disgusted with his cowardice, scrambled up the side of the ravine again, and strolled back to where they were still delving away among the rubbish. They took no notice of me, and I lit a cigarette with deliberation before I inquired if they had found anything.

“Ouf! but you annoy me with your questions,” snapped Lessaution. “Is it that you expect us to examine the whole of this affair in ten minutes? This is the discovery of the century—the most magnificent one that has been made about peoples of which we know nothing. And you say have you found anything? We have found a house, and have been here the littlest half-hour.”

“Ah,” said I superciliously; “I think you’re wasting your time.”

He boiled over at me, his face the color of beetroot.

“Can you not search for your beach without disturbing the important investigations of savants? What is your beach to me? Go you on and look for it, and leave us to dig at our leisure.” He snorted with indignation as he turned away.

“Well,” said I apathetically, “of course you know best. If this roofless hovel is enough for you, well and good. But when a few hundred yards away a whole city awaits your inspection, I should have thought——”

“What!” they all bawled, leaping up. “Where? Which?” and they stared round them as if they expected to see it perched on the adjoining precipices.

“Anywhere but where you’re looking,” I returned dryly. “There, if you’re so anxious to know,” and I pointed into the depths of the glacier.

“But how——” began Gerry.

“By the front door,” said I, interrupting. “There’s a passage right into the heart of it, and here have you all been idling about this one outlying bothie, while Parsons and I with some show of energy have been finding out——” It was no use continuing, for they had all forsaken me and raced down the slope toward the baggage, bawling aloud to Parsons for the candles. I followed at a more leisurely pace, and before I had time to overtake them, they had disappeared into the cavern with the only two lights. As I did not feel inclined to follow in the dark, I sat myself down to inspect the meat pie, and await their return.

They came staggering out in about half-an-hour, bearing something between the three of them. What sense of decency or of the fitness of things they possessed I don’t know, but it was the mummy they’d got, arranged on a sort of hammock of their coats, which they carried by the sleeves. The unfortunate corpse rolled and crumbled hideously as it came thus immodestly out into the sunlight after its centuries of seclusion. I could not restrain my indignation. Even Parsons was moved.

“It ain’t ’ardly decent,” he observed, looking across at me.

“I think you’re the most disreputable scoundrels I ever came across,” said I warmly, advancing upon the party. “You’re worse than Burke or Hare. Why couldn’t you let the wretched carcass sleep in peace?”

“Humbug!” quoth Gerry discourteously. “D’you think we’re going to let the only Mayan extant rot away in the bowels of a glacier for want of a little embalming? The Professor’s going to stuff it.”

“Oh, he is, is he?” said I, and smiled into my mustache. I had a good idea of what would occur when this worn carrion had been out in the sunlight for an hour or two. “I wish him joy,” I added politely.

They set it down upon a smooth lump of granite, and the Professor tripped round it ecstatically. Denvarre and Gerry listened to his chatterings with the solemn attention of profound ignorance, and Parsons eyed the whole proceeding with melancholy and distrust. The sun was exceedingly powerful, and I lit another cigarette. After about ten minutes I sniffed suspiciously.

“Your beastly mummy’s waking up,” I hazarded. “There’s a confounded smell of musk.”

Lessaution opened his mouth to answer me. His eyes were agleam with native fire, and his podgy little nostrils and upper lip were curled into a sneer. I perceived that he proposed to wither me with a torrent of sarcasm.

As he stood opposite me his gaze took in the whole of the upper valley over my shoulder. Instead of the volley of winged words that I expected, the only sound that escaped between his teeth was a raucous croak. His mouth stayed, gaping widely. The fire died from his eyes, and I saw terror settle in them like a gray mist. His cap rose distinctly an inch upon his head, and he splayed out his hands before him, thrusting away from his white face as if to keep off a horror unimaginable.

We four wheeled in our tracks. Then my throat dried up within me; my lips twitched; my knees were stricken with sudden palsy. For if ever nightmare walked abroad embodied on God’s earth, it was there confessed before my eyes.