CHAPTER XVI

THE TEMPLE AND THE LAIR OF CAY

Though during the days of hard work, while the boat was being launched, we continued to live in the ship, we did so by compulsion of necessity alone, not having the time to seek another dwelling-place. Now the strain was over, we felt that it behoved us to seek shelter elsewhere, since another shock of earthquake might easily destroy the Racoon and leave us utterly without abode in this land of desolation. Therefore we cast about for a refuge which should be stable enough to withstand earthquakes, and also form a protection in case the Beast came down upon us.

Several moderate-sized peaks rose from the glacier foot. They were precipitous in parts, but broken with ledges and crevices, making their ascent arduous, but by no means difficult. One of these, a mass of granite shaped something like a pyramid with a flattened top, seemed to meet the case admirably. The breadth of its base made it unlikely that it would topple however much it might be shaken, and its summit was scarred with deep clefts. Any of these might be roofed over with a few planks to make a famous shelter.

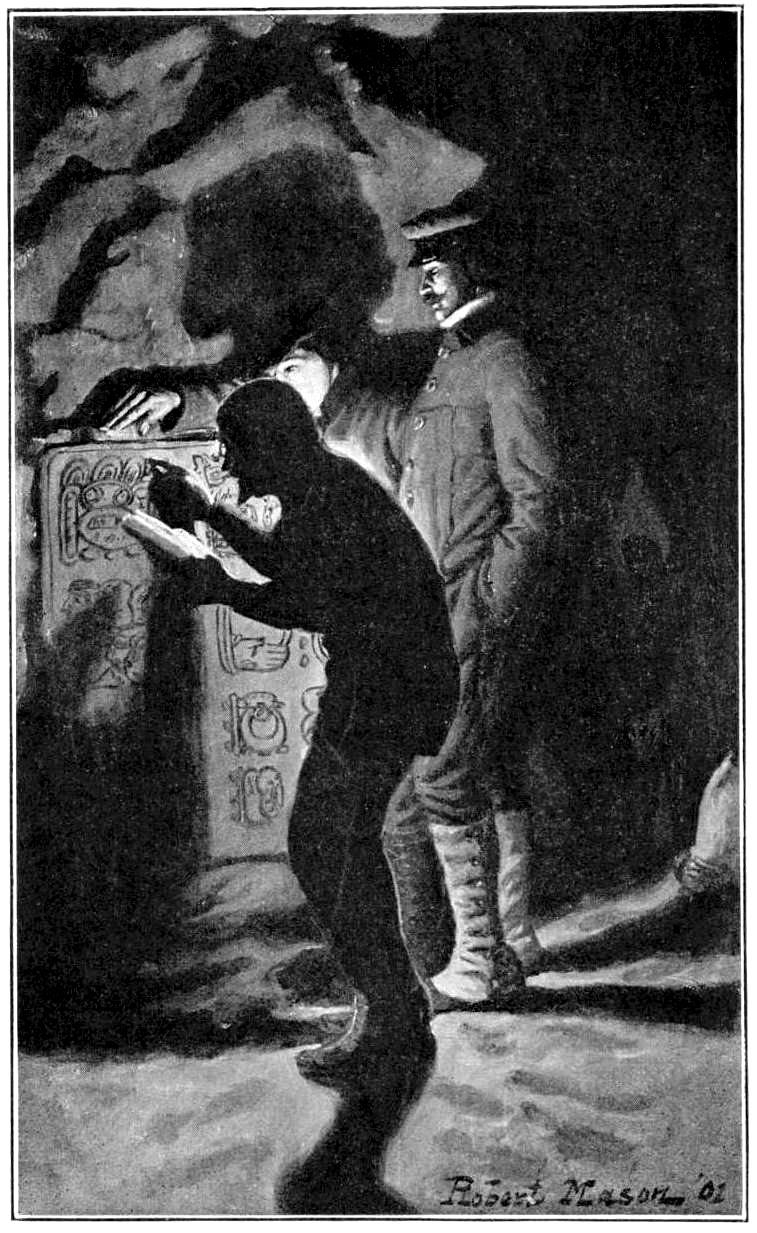

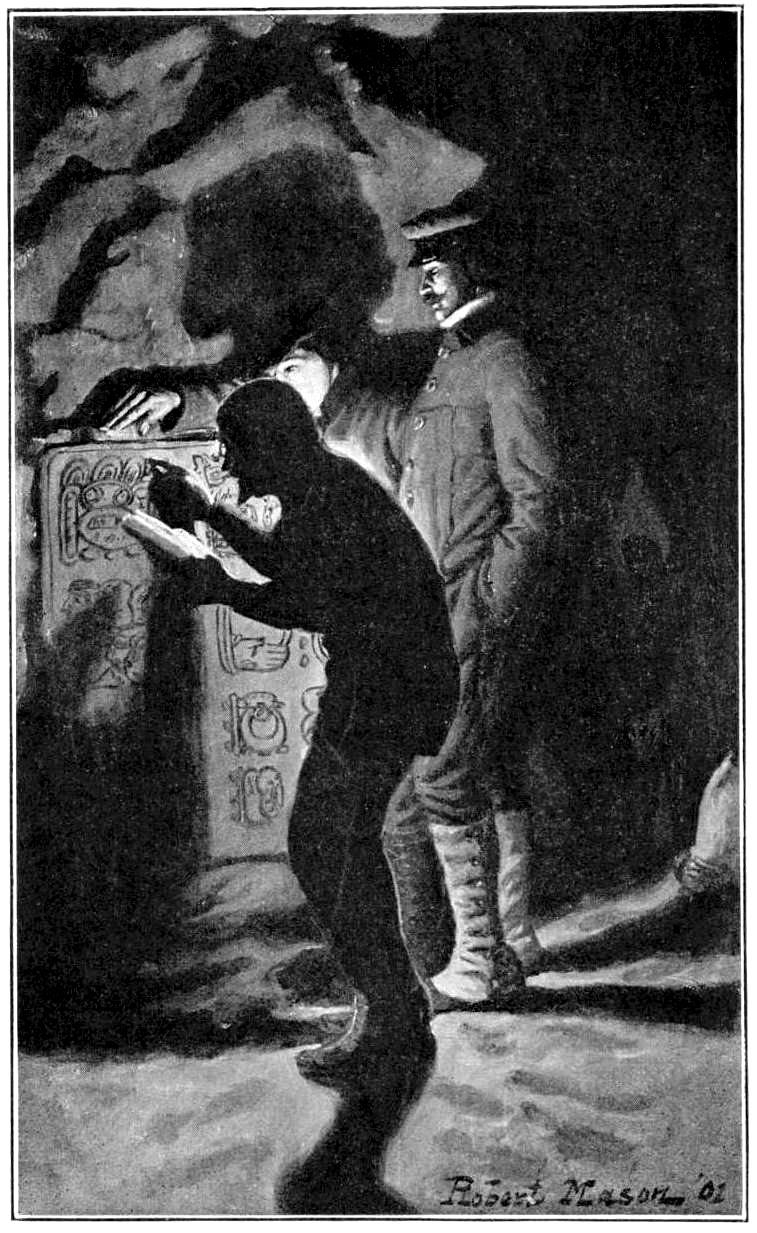

IT WAS THE LAST WORSHIP OF THE PRIEST OF CAY.

Janson and I made the ascent with some of the crew and made examination of the spot. We got up some timbers and a tarpaulin or two and soon arranged an excellent series of little cabins, sufficient to house the whole party if the need arose. We transported up to this eyrie a certain proportion of our provisions and stores, arranged hammocks for ourselves and cots for the ladies, and then felt that we had a satisfactory alternative abode if the ship should fail us.

This being accomplished, we had time and opportunity to turn to less pressing matters. We set forth on the following morning therefore to investigate the matter of the Mayan temple beneath the glacier, anent which Lessaution had muttered many jealous words during the last six or seven days. For he openly declared that Gerry and I wished to keep the glory of this discovery intact, and were delaying his entrance into its mysteries of malice prepense.

We took our ropes, poles, and a ladder to the cliff-top, found the crevasse, which we had marked with a cross hewn in the ice, and according to promise lowered the Frenchman first therein. I followed him, and in due order came Gerry, Denvarre, and Garlicke.

I found the little Professor trotting round the temple, exclamations of wonder and delight hurtling from between his teeth. His little arms waved, his little lean face beamed with scientific glee. His self-made dictionary and his grammar of the Mayan symbols was in his hands. In the pauses of his ecstasy he was trying to divine the inscriptions. Now and again he stopped to examine the prone figures of the shrivelled priests, turning them about and picking at them with a minuteness that struck me as both hard-hearted and indelicate. Finally he dragged himself out of this haphazard abandon of discovery, and settling down before the base of the great pedestal, began to decipher the inscriptions with serious attention.

For some few minutes he sat silently between Gerry and myself, who held candles by him. He conned the twisted devices, turning from them to his note-book, and tracing out each symbol carefully. Suddenly signs of the greatest excitement manifested themselves. He jumped up with an exclamation, nearly upsetting both of us, and rushed round to the back of the image. Here he began to butt at the solid stone in a manner that seemed little short of imbecile.

In the midst of these scrabblings a panel—as it seemed—gave beneath his hand; we stared wonderingly as a door slid open at his very feet.

Two steps were revealed, dropping down into a chamber in the stone. Into the blackness of this vault our friend flung himself, chattering furiously in French, without waiting to be offered a light. We only stayed for an additional candle to be lit and then followed him smartly.

It was a small dark room, and without exit to the air save by the way we had entered. Round the sides of rock-hewn wall ran a slab. Upon it were arranged various basons, salvers, spits, and other sacrificial instruments to which we could give neither names nor use. But what made our eyes sparkle and our breath come short and ecstatically, was the fact that each and all of these outlandish vessels shone yellow and lustrous in the candle-light. They were in no degree discolored by age or by damp. At the which we knew that here indeed we had fallen upon the Mayan booty of which my uncle had spoken—“the ancestral treasures of that hapless race.”

We stared with greedy eyes upon this hidden hoard. With awesome fingers we touched and handled the beakers, the basons, and the curious two-pronged forks and skewers. All bore traces of use, but we were at a loss to account for the jagged notches in the handles of some of the sword-like spits. They leaned against the rocky ledge, arranged in exact order along the floor. At the upper part of each were wavering scars in solid metal; we might have imagined them to be decorative patterns, but for their scratchiness and irregularity. I took one in my hands and examined it carefully.

It had a hilt about half-a-foot long at the thickest end. It was just below this that the dents eat into the metal. I caught hold of Lessaution by the arm to demand his explanations of this matter.

At first he contemned my curiosity, explaining that matters of much greater interest demanded his attention. He ran his fingers over the criss-cross work, and suddenly shuddered, handing the thing back to me with a repellent gesture.

“It is explained there,” he said, pointing to the device that ran above the ledge. “Those are the rituals of sacrifice. It is necessary to slay the victim according to the religion of Cay. So they stab the sword through the shoulder and pierce the lung, and the victim dies slowly—very slowly, and he calls for long. So they think the god is well pleased. Then the poor people who die, they are in agonies—ah, so great a pain, and they bite and snap at the handle with their teeth. So here we see the marks. It is not nice—that, no it is of the most horrible. But what would you? They were brutes, this people, but oh, so ancient,” and he shrugged his shoulders as if much might be forgiven to a people who had conducted their devilries from time immemorial.

I dropped the thing with a shiver and a tingling of my fingers. Brutes they were, indeed, these fearsome Mayans of the centuries of long ago. I could only give fervent thanks that they were not alive to welcome us to these savage shores. I could well imagine the delight that would be theirs in spitting us on their horrible prongs, and leaving us to slow agony, tickling, as they would doubtless believe, their god’s ears with our delightful tortures. And if they had not left us to pant out our lives before this bestial image, we should have been offered up alive to the monster himself, to meet a swifter doom, perhaps, but one as fearful.

I asked him how he was so sure of the matter. He explained that the whole of the devices that ran round the walls were the detailed dogma and rubric of the worship of Cay. Not only did these give full directions for sacrificial orgies, and prescribe particularly the transfixing of the victims in the manner spoken of, but also alluded to the keeping alive of these tormented wretches—I am only quoting from what he translated—with various drugs, the names of which he was unable to understand. The inscription laid stress on the fact that the cries of these unfortunates were beloved of the god, and that, therefore, they were to be prolonged as far as possible.

It was only to be considered natural that the worship of such a filthy monstrosity should breed degraded cruelties, but I puzzled my head to think how Mayans in Central America could have possibly divined the existence of anything resembling this antediluvian Horror in the Antarctic Circle. I questioned Lessaution on this point also.

He said that his researches had led him to think that the last home of the Mastodon had been in Central America, and that before he became extinct he might have become the holy beast of the Mayan religion, much as the bull is to the Hindoos. He went on to explain his theory that as by lapse of time the huge beast became a memory and a myth, he rose from being a symbol of the godhead to being confounded with the god himself. His proportions had probably been exaggerated by half-forgotten rumor, and with his size had grown his sacredness. To make themselves strong the priesthood had invented the human sacrifices, by which, doubtless, they could remove their special antipathies or heretics.

It was not surprising, he added, that the Mayans, born and nurtured in the service of this superstitious horror, should conceive the Dinosaur, when he thus descended upon them, to be their god in very deed. We must also reckon the effect their miraculous bringing to this desolate coast would have upon them. There was no doubt that they had frequently striven to do their divinity honor by human sacrifices, and that one of their first acts must have been the building of this temple under the shadow of the overhanging rock.

It was to be supposed that the glacier had been diverted from its former channel by some earthquake shock, and had poured upon the building from above, bringing to utter destruction the town that had stood round it, the only exceptions being the house we had found upon the mountain-side, and the one Parsons and I had discovered in the glacier. This last had been saved by the shielding cliff above it, though walled in by impenetrable thicknesses of ice.

The priests of Cay, evidently fanatic to the last, had seen no chance of escape. They had stored away their golden vessels, swept and garnished their sanctuary, and then lain down in grim hopelessness to die at the feet of their god. Swiftly numbed by the overpowering cold, without provision or proper clothing, they had passed away in silent submission to the decrees of fate, and probably without much feeling or pain. Lessaution surmised that the lone corpse Parsons and I had stumbled upon in the other dwelling was the remains of some unfortunate wretch who had been longer fortified by food and raiment, and who had fought the cold with full knowledge of the ultimate issue. So in solitude and great fear he had met his death.

I pondered these ideas of the Professor’s while we collected together the vessels of the sanctuary. We roped them up in heaps, and transported them to the foot of the ice-hill. Then we signalled to Rafferty, whom we had left above in charge of half-a-dozen of the sailors, and had the pleasure of seeing our trove whizz up into the sunshine, to be bestowed finally in the lockers of the ship, there to await the possibilities of our ultimate rescue.

As the last sheaf of spits disappeared into the gloom of the roof, we turned for further explorations. Lessaution held—and we felt that there might be something in it—that by following the course of the ice-stream that tinkled into the channel at the extreme end of the cave, we might chance upon other remains of the Mayan village, or at any rate find more relics of their community. Not wishing to leave any chance untried of discovering all we could of this strange people’s habitation, we lit dips, took one apiece, and crawled into the mouth of the waterway.

It was low-roofed and narrow, and we groped and splashed along it like rats in a sewer. The light played and spangled on the ice walls, and the gurgle of the ripples and our splashings re-echoed hollow and gloomily. A draught sang back into our faces, making the candles sputter noisily. We thought that we must be approaching an outer entrance, though no light came through the ice. We wondered if by any chance we were in any communicating by-way of the cavern that Parsons and I had first explored.

Suddenly the ice faded from about us, and with the falling splash of a small cascade the rivulet ran into an opening in a rock wall which faced us.

This we took to be without doubt the overhanging side of the mountain which backed the basin in which lay our ship. We peered down the tunnel, and seeing the fall to be but a foot or two ventured in. For the first fifty yards the way was straight enough, but then began to turn and twist deviously, narrowing, though it grew higher. We easily understood that the water had worn a way through the granite by eating out a lode of softer mineral. We were enabled to walk erect, though I heard Lessaution grunt complainingly behind me as he squeezed through the narrows, where the sides reached out to one another sharply.

A couple of hundred yards more, and a turn—sharper than any we had yet passed—whipped us round almost in our tracks. Before I could realize it we were striding out into a great hall in the granite, and the stream was almost lost in the sandy floor.

With the disappearance of the reflecting walls the darkness seemed to swallow the thin light of our candles utterly. A heavy effluvia-like smell hung in the air. In the act of wheeling round to speak to my companions I tripped. I plunged forward, grasping the elusive sand, and ploughing a groove in it with my chin.

My candle went out as I struck the ground, but before its light snapped into nothingness I saw beside my face five long yellow objects spreading out ghastlily distinct upon the dark floor. Looking back I saw the obstruction over which I had stumbled begin to roll slowly from between me and the lights of my companions. It was silhouetted in irregular dents and jaggednesses against the dim illumination. I also saw the long yellow gleams move lingeringly from beside me in the twilight.

A yell went up from the others, and an odor still more pungent assailed my nostrils. I heard the slow, lurching sound of a heavy body churning the silt of the floor. But it needed not that to tell me in what plight I was. We had penetrated to the very lair of the Monster. I had fallen headlong across his tail as it stretched in my path. Beside me was his webbed foot; my face nearly touched his clammy nails.

He was turning—turning—turning; in another second his huge neck would swing round upon me; I should be a mere swelling in that monstrous throat.

My knees were palsied by a terror that scarcely allowed me to rise. My joints were as water within me. If ever man realized the terrors of nightmare in the flesh, I did so during those two fearful seconds when I scrambled to my feet, and raced across the ten yards that separated me from the mouth of the tunnel in the rock. I leaped into it like a rabbit before the greedy jaws of a terrier.

The others were already jammed in its narrow recesses. As I joined them the last light fell into the stream with a hiss. Kicking, reeling, panting, snatching at each other and at the rocks, we fought along that pipe-like passage, every nerve in our bodies tingling with expectant terror. My hair bristled on my head as I heard the snap of those grim jaws behind me, and for one awful moment I felt the horrible breath sing past my cheek. I ducked to very earth, and at the same moment felt the rasp of the eager tongue upon my heel. Calling aloud in abject terror I plunged forward, bearing down Gerry and Lessaution with me. We struggled together in the darkness, splashing up a little stream, and wallowing in the turbid mud, while above our very heads, it seemed, we could hear the hiss and pant of the straining lips. On hands and knees we jostled and crawled in the darkness.

As we drew away from the sounds behind us, I managed after a nervous effort or two to strike a vesta. The match sputtered, flared, and then burnt up steadily. Lessaution was still grasping his extinguished dip, and thrust the wick into the flame. As it took fire he held it up, and in its steady light we saw the nearness of our escape.

Not ten yards away the long neck strained and weaved desperately, bowing towards us with frantic efforts. The wicked green eyes flamed, and the teeth snapped and chattered greedily. The murky breath from between them flooded the cavern noisomely. The whole horrible scene stood out in frightful distinctness against the background of dark rock.

Then the dip-flame reached Lessaution’s fingers, and with a curse he dropped it. The fall of the darkness upon that brief but all too vivid glimpse of horror unmanned us all. With a gasp we turned and fled recklessly into the darkness of the waterway without waiting for a light, paddling and splashing through the pools, tripping each other up, reeling, wrestling, smiting and bruising our limbs against the rocks. Finally with bleeding fingers, and wet with perspiration and roof-drip we stumbled out into the dimness of the temple cave, panting, dishevelled, like whipped curs, coughing still with the vile stench of that fearful kennel, shivering yet with the narrowness of our escape.

With broken sentences and half-coherent words we arranged the order of our ascent, and were hauled up one by one. With grateful lungs and dazzled eyes we greeted the freshness of the glacier slopes, though it was with dejected mien we slunk back to the ship. We sought victual, and later, tobacco, discussing the same on deck for appreciable minutes before any one ventured to refer to our adventure, even Lessaution’s fund of conversation being dried up by his sense of defeat.

It was Garlicke who opened the conversation, and from a sporting point of view. He is a sort of sans appel on the subject of weapons of the chase, being a noted man at the running deer and such-like competitions, as well as a keen game shot. He demonstrated that the sporting Männlicher rifle was the instrument marked out for the destruction of the Monster, giving his reasons for supposing that its bullet would penetrate any hide, provided that the missile had a hollow point. He regretted intensely that he had not had one of these useful implements at hand during the late rencontre.

Then the babble joined upon this issue and others flowing from it, and we felt our nerves grow back to us with our words, each of us expressing the opinion that to the determined man, armed with modern weapons, Dinosaurs were not necessarily invulnerable, and each asking, on reflection, no better than to beard the Beast again in his lair with suitable arms.

In which wordy tournament Lessaution, as was to be expected, rode triumphant down the lists, being willing, so he assured us, to compete with the Great Atrocity, equipped with no more than his native intelligence and a squirt.

This latter he proposed to fill with diluted prussic acid—of the commodity in question we possessed not a molecule, which he regarded as beside the question—and therewith advance down the passage up which two hours before he had so ingloriously fled. Arriving within range of the gaping mouth, he would fill it with the fatal fluid. But one frightful writhe and M. le Dinosaure would lie dead at his feet. V’là tout.

This versatile proposal was met with abounding laughter, the which daunted him in no degree, but cheered us all immensely. For with laughter returned self-respect, which had dropped from us in its entirety during the disgraceful rout of the morning, and we shook our fear from us as dogs shake their dripping coats. To each came great resolves to personally seek out and destroy the Monster, and complacent with the future renown thus inwardly promised, each turned patronizing attention to the talk of his fellows, using their banal conversation to cloak the deep and secret devices that seethed within his own brain. So content grew beneath the cloud of tobacco smoke, and pleasant talk expanded itself, and finally the ladies, under the persuasive tinkling of Gerry’s banjo, consented to enliven the rocky solitudes with a song.