CHAPTER IX.

THE DUEL

NOW we placed our ears against the panelling and listened. First we heard creaks that were loud in the stillness, then soft heavy noises such as are made by a cat when it jumps from a height to the ground, and a gentle rubbing as of stockinged feet upon the floor. After this for some seconds came silence that presently was broken by the clink of steel, and the sound of heavy blows delivered upon a soft substance with swords and knives. The murderers were driving their weapons through the bed-clothes, thinking that we slept beneath them. Next we heard whisperings and muttered oaths, then a voice, Don José’s, said:

“Be careful, the beds are empty.”

Another instant and candles were lit, for their light reached us through small peep-holes in the panel, and by putting our eyes to these we could see what passed in the room. There before us we beheld Don José, Don Smith, and four of their companions, all armed with knives or machetes, while, framed, as it were in the wall, in the place that had been occupied by the picture of the abbot, stood our host, Don Pedro, holding a candle above his head, and glaring with his fish-like eyes into every corner of the room.

“Where are they?” he said. “Where are the wizards? Find them quick and kill them.”

Now the men ran to and fro about the chamber, dragging aside the beds and staring at the pictures on the wall as though they expected to see us there.

“They are gone,” said José at length, “that Indian, Ignatio, has conjured them away. He is a demonio and not a man; I thought it from the first.”

“Impossible!” cried Don Pedro, who was white with rage and fear. “The door has been watched ever since they entered it, and no living thing could force those bars. Search, search, they must be hidden.”

“Search yourself,” answered Don Smith sullenly, “they are not here. Perhaps they discovered the trick of the picture and escaped down the passages to the chapel.”

“It cannot be,” said Don Pedro again, “for just now I was in the chapel and saw no signs of them. We have some traitor among us who has led them from the house; by Heaven, if I find him out——” and he uttered a fearful oath.

“Shall we bring the dogs?” asked José,—and I trembled at his words: “they might smell their footing.”

“Fool, what is the use of dogs in a place where all of you have been tramping?” answered the father. “To-morrow at dawn we will try them outside, for these men must be found and killed, or we are ruined. Already the authorities suspect us because of the disappearance of the two Americanos, and they will send soldiers from Vera Cruz to shoot us down, for without doubt this Inglese is rich and powerful. It is certain that they are not here, but perhaps they are hidden elsewhere in the building. Come, let us search the passages and the roof,” and he vanished into the wall, followed by the others, leaving the chamber as dark and silent as it had been before their coming.

For a while the danger had passed, and we pressed each other’s hands in gratitude, for to speak or even to whisper we did not dare. Ten minutes or more went by, when once again we heard sounds, and a light appeared in the room, borne in the hand of Don Pedro, who was accompanied by his son, Don José.

“They have vanished,” said the old man, “the devil their master knows how. Well, to-morrow we must hunt them out if possible, till then nothing can be done. You were a fool to bring them here, José. Have I not told you that no money should tempt me to have more to do with the death of white men?”

“I did it for revenge, not money,” answered José.

“A nice revenge,” said his father, “a revenge that is likely to cost us all our lives, even in this country. I tell you that, if they are not found to-morrow and silenced, I shall leave this place and travel into the interior, where no law can follow us, for I do not wish to be shot down like a dog.

“Listen, José, bid those rascals to give up the search and go to bed, it is useless. Then do you come quietly to my room, and we will visit the Indian and his daughter. If we are to screw their secret out of them, it must be done to-night, for, like a fool, I told that Englishman the story when the wine was in me, thinking that he would never live to repeat it.”

“Yes, yes, it must be to-night, for to-morrow we may have to fly. But what if the brutes won’t speak, father?”

“We will find means to make them,” answered the old man with a hideous chuckle; “but whether they speak or not, they must be silenced afterwards——” and he drew his hand across his throat, adding, “Come.”

An hour passed while we stood in the hole trembling with excitement, hope, and fear, and then once more we heard footfalls, followed presently by the sound of a voice whispering on the further side of the panel.

“Are you there, lord?” the whisper said. “It is I, Luisa.”

“Yes,” I answered.

Now she touched the spring and opened the panel.

“Listen,” she said, “they have gone to sleep all of them, but before dawn they will be up again to search for you far and wide. Therefore you must do one of two things; lie hid here, perhaps for days, or take your chance of escape at once.”

“How can we escape?” I asked.

“There is but one way, lord, through the chapel. The door into it is locked, but I can show you a place from which the priests used to watch those below, and thence, if you are brave, you can drop to the ground beneath, for the height is not great. Once there, you can escape into the garden through the window over the altar, which is broken, as I have seen from without, though to do so, perhaps, you will have to climb upon each other’s shoulders. Then you must fly as swiftly as you can by the light of the moon, which has risen. The dogs have been gorged and tied up, so, if the Heart is your friend, you may yet go unharmed.”

Now I spoke to the señor, saying:

“Although the woman does not know it, I think it likely that we shall find company in this chapel, seeing that the Indian and his daughter are imprisoned there, where Don Pedro and José have gone to visit them. The risk is great, shall we take it?”

“Yes,” answered the señor after a moment’s thought, “for it is better to take a risk than to perish by inches in this hole of starvation, or perhaps to be discovered and murdered in cold blood. Also we have travelled far and undergone much to find this Indian, and if we lose our chance of doing so, we may get no other.”

“What do you say, Molas?” I asked.

“I say that the words of the señor are wise, also that it matters little to me what we do, since whether I turn to left or right death waits me on my path.”

Now one by one we climbed through the false panel, and by the light of the moon Luisa led us across the chamber to the spot between the beds, where hangs the picture of the abbot, which picture, that is painted on a slab of wood, proved to be only a cunningly devised door constructed to swing upon a pivot.

Placing her knee on the threshold of the secret door, Luisa scrambled into the passage beyond. When the rest of us stood by her side, she closed the panel, and, bidding us cling to one another and be silent, she took me by the hand and guided us through some passages till at length she whispered:

“Be cautious now, for we come to the place whence you must drop into the chapel, and there is a stairway to your right.”

We passed the stairway and turned a corner, Luisa still leading.

Next instant she staggered back into my arms, murmuring, “Mother of Heaven! the ghosts! the ghosts!” Indeed, had I not held her she would have fled. Still grasping her hand, I pushed forward to find myself standing in a small recess—the one I showed you, Señor Jones—that was placed about ten feet above the floor of the chapel, and, like other places in this house, so arranged that the abbot or monk in authority, without being seen himself, could see and hear all that passed beneath him.

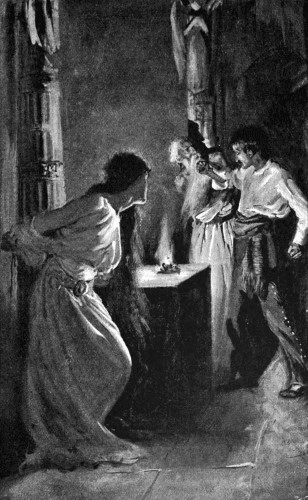

Of one thing I am sure, that during all the generations that are gone no monk watching here ever saw a stranger sight than that which met my eyes. The chancel of the chapel was lit up by shafts of brilliant moonlight that poured through the broken window, and by a lamp which stood upon the stone altar. Within the circle of strong light thrown by this lamp were four people, namely, Don Pedro, his son Don José, an old Indian, and a girl.

On either side of the altar then, as now, rose two carven pillars of sapote wood, the tops of which were fashioned into the figures of angels, and to these columns the old Indian and the woman were tied, one to each column, their hands being joined together at the back of the pillars in such a manner as to render them absolutely helpless. My eyes rested first upon the woman, who was nearest to me, and seeing her, even as she was then, dishevelled, worn with pain and hunger, her proud face distorted by agony of mind and impotent rage, I no longer wondered that both Molas and Don Pedro had raved about her beauty.

She was an Indian, but such an Indian as I had never known before, for in colour she was almost white, and her dark and waving hair hung in masses to her knees. Her face was oval and small-featured, and in it shone a pair of wonderful dark-blue eyes, while the clinging white robe she wore revealed the loveliness of her tall and delicate shape.

Bad as was the girl’s plight, that of the old man her father, who was none other than the Zibalbay we had come to seek, seemed even worse. As Molas had described him, he was thin and very tall, with white hair and beard, wild and hawk-like eyes, and aquiline features, nor had Don Pedro spoken more than the truth when he said that he looked like a king. His robe had been torn from him, leaving him half naked, and on his forehead, breast, and arms were blood and bruises which clearly had been caused by a riding-whip that lay broken at his feet.

It was not difficult to guess who had broken it, for in front of the old man, breathing heavily and wiping the perspiration from his brow, stood Don José.

“This mule won’t stir,” he said to his father in Spanish; “ask the girl, it must wake her up to see the old man knocked about.”

Then Don Pedro slipped off the altar rail upon which he had been seated, and, advancing to the woman, he peered at her with his leaden eyes:

“My dear,” he said to her in the Maya language, “this sight must grieve you. Put an end to it then by telling us of that place where so much gold is hidden.”

“As with my last breath, daughter,” broke in Zibalbay, “I command you to say nothing, no, not if you see them murder me by inches before your eyes.”

“Silence, you dog,” said Don José, striking him across the lips with his hand.

“Oh! that I were free to avenge you!” gasped the girl as she strained and tore at the ropes which held her.

‘Oh! that I were free to avenge you!’

“Don’t be in a hurry, my love,” sneered Don José, “wait a while and you will have yourself to avenge as well as your father. If he won’t speak I think we can find a way to make you talk, only I do not want to be rough with you unless I am forced to it. You are too pretty, much too pretty.”

The girl shivered, gasping with fear and hate, and was silent.

“What shall we try him with now?” he went on, addressing Don Pedro; “hot steel or cold? Make up your mind, for I am growing tired. Well, if you won’t, just hand me that machete, will you? Now, friend,” he said, addressing the Indian, “for the last time I ask you to tell us where is that temple full of gold, of which you spoke to your daughter in my father’s hearing?”

“There is no such place, white man,” he answered sullenly.

“Indeed, friend! Then will you explain where you found those little ingots, which we captured from the Indian who had been visiting you, and whence came this machete?” and he pointed to the weapon in his hand.

It was a sword of great beauty, as I could see even from where we stood, made not of steel, but of hardened copper, and having for a handle a female figure with outstretched arms fashioned in solid gold.

“The machete was given to me by a friend,” said the Indian, “I do not know where he got it.”

“Really,” answered José with a brutal laugh, “perhaps you will remember presently. Here, father, warm the point of the machete in the lamp, will you, while I tell our guest how we are going to serve him and his daughter.”

Don Pedro nodded, and, taking the sword, he held the tip of it over the flame, while José bending forward whispered into the Indian’s ear, pointing from time to time to the girl, who, overcome with faintness or horror, had sunk to the ground, where she was huddled in a heap half hidden by the masses of her hair.

“Are you white men then devils?” said the old man at length, with a groan that seemed to burst from the bottom of his heart, “and is there no law or justice among you?”

“Not at all, friend,” answered José, “we are good fellows enough, but times are hard and we must live. As for the rest, we don’t trouble over much about law in these parts, and I never heard that unbaptised Indian dogs have any right to justice. Now, once more, will you guide us to the place whence that gold came, leaving your daughter here as hostage for our safety?”

“Never!” cried the Indian, “better that we two should perish a hundred times, than that the ancient secrets of my people should pass to such as you.”

“So you have secrets after all! Father, is the sword hot?” asked José.

“One minute more, son,” said the old man, quietly turning the point in the flame.

This was the scene that we witnessed, and these were the words that astonished our ears.

“It is time to interfere,” muttered the señor, and, placing his hand upon the rail, he prepared to drop into the church.

Now a thought struck me, and I drew him back to the passage.

“Perhaps the door is open,” I said.

“Are you going in there?” asked the girl Luisa.

“Certainly,” I replied; “we must rescue these people, or die with them.”

“Then, señors, farewell, I have done all I can for you, and now the saints must be your guide, for if I am seen they will kill me, and I have a child for whose sake I desire to live. Again, farewell,” and she glided away like a shadow.

We crept forward down the stair. At the foot of it was a little door, which, as we had hoped, stood ajar. For a moment we consulted together, then we crawled on through the gloom towards the ring of light about the altar. Now José had the heated sword in his hand.

“Look up, my dear, look up,” he said to the girl, patting her on the cheek. “I am about to baptize your excellent father according to the rites of the Christian religion, by marking him with a cross upon the forehead,” and he advanced the glowing point of the sword towards the Indian’s face.

At that instant Molas pinned him from behind, causing him to drop the weapon, while I did the same office by Don Pedro, holding him so that, struggle as he might, he could not stir.

“Make a sound, either of you, and you are dead,” said the señor, picking up the machete and placing its hot point against José’s breast, where it slowly burnt its way through his clothes.

“What are we to do with these men?” he asked.

“Kill them as they would have killed us,” answered Molas; “or, if you fear the task, cut loose the old man yonder and let him avenge his own and his daughter’s wrongs.”

“What say you, Ignatio?”

“I seek no man’s blood, but for our own safety it is well that these wretches should die. Away with them!”

Now Don Pedro began to bleat inarticulately in his terror, and that hero, José, burst into tears and pleaded for his life, writhing with pain the while, for the point of the sword scorched him.

“You are an English gentleman,” he groaned, “you cannot butcher a helpless man as though he were an ox.”

“As you tried to butcher us in the chamber yonder,—us, who saved your life,” answered the señor. “Still, you are right, I cannot do it because, as you say, I am a gentleman. Molas, loose this dog, and if he tries to run, put your knife through him. José Moreno, you have a sword by your side, and I hold one in my hand; I will not murder you, but we have a quarrel, and we will settle it here and now.”

“You are mad, señor,” I said, “to risk your life thus, I myself will kill him rather than it should be so.”

“Will you fight if I loose you, José Moreno?” he asked, making me no answer, “or will you be killed where you stand?”

“I will fight,” he replied.

“Good. Let him free, Molas, and be ready with your knife.”

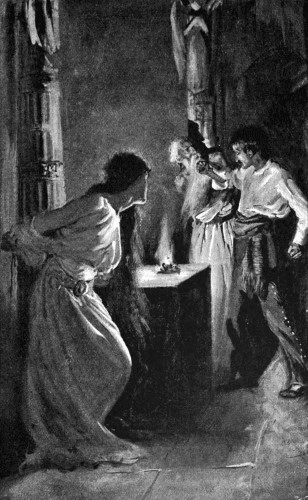

“I command you,” I began, but already the man was loose and the señor stood waiting for him, his back to the door, and grasping the Indian machete handled with the golden woman.

Now José glanced round as though he sought a means of escape, but there was none, for in front was the machete and behind was the knife of Molas. For some seconds—ten perhaps—they stood facing each other in the ring of the lamp-light, whilst the moonbeams played faintly about their heads. We watched in utter silence, the Indian girl shaking the long hair from her face, and leaning forward as far as her bonds would allow, that she might see this battle to the death between him who had insulted and tormented her, and the noble-looking white man who had appeared out of the gloom to bring her deliverance.

It was a strange scene, for the contrast of light and darkness, or of good and evil, is not greater than was that of these two men, and what made it stranger were the place and hour. Behind them was the half-lit emptiness of the deserted chapel, before them stood the holy crucifix and the desecrated altar of God, and beneath their feet lay the bones of the forgotten dead, whose spirits mayhap were watching them from the shadows as earnestly as did our living eyes. Yes, that midnight scene of death and vengeance enacted in the House of Peace was very strange, and even now it thrills my blood to think of it.

From the moment that I saw them fronting each other, my fears for the issue vanished. Victory was written on the calm features of the señor, and more especially in his large blue eyes, that of a sudden had grown stern as those of an avenging angel, while the face of José told only of baffled fury struggling with bottomless despair. He was about to die, and the terror of approaching death unnerved him.

Still it was he who struck the first, for, stepping forward, he aimed a desperate blow at the señor’s head, who, springing aside, avoided it, and in return ran him through the left arm. With a cry of pain, the Mexican sprang back, followed by the señor, at whom he cut from time to time, but without result, for every blow was parried.

Now they were within the altar rails, and now his back was against one of the carved pillars of sapote wood,—that to which the girl was tied. Further he could not fly, but stayed there, laying about him wildly, so that the woman at the other side of the pillar crouched upon the ground to avoid the sweep of his sword.

Then the end came, for the señor, who was waiting his chance, drew suddenly within reach, only to step back so that the furious blow aimed at his head struck with a ringing sound upon the marble floor, where the mark of it may yet be seen. Before Don José, whose arm was numbed by the shock, could lift the sword again, the señor ran in, and for the second time thrust with all his strength. But now the aim was truer, for his machete pierced the Mexican through the heart, so that he fell down and died there upon the altar step.

Now I must tell of my own folly that went near to bringing us all to death. You will remember that I was holding Don Pedro, and how it came about I know not, but in my joy and agitation I slacked my grip, so that with a sudden twist he was able to tear himself from my hands, and in a twinkling of an eye was gone.

I bounded after him, but too late, for as I reached the door it was slammed in my face, nor could I open it, for on the chapel side were neither key nor handle.

“Fly,” I cried, rushing back to the altar, “he has escaped, and will presently be here with the rest.”

The señor had seen, and already was engaged in severing with his sword the rope that bound the girl, while Molas cut loose her father. Now I leapt upon the altar—may the sacrilege be forgiven to my need—and, springing at the stonework of the broken window, I made shift to pull myself up with the help of Molas pushing from below. Seated upon the window ledge I leaned down, and catching the Indian Zibalbay by the wrists, for he was too stiff to leap, with great efforts I dragged him to me, and bade him drop without fear to the ground, which was not more than ten feet below us. Next came his daughter, then the Señor, and last of all, Molas, so that within three minutes from the escape of Don Pedro we stood unhurt outside the chapel among the bushes of a garden.

“Where to now?” I asked, for the place was strange to me.

The girl, Maya, looked round her, then she glanced up at the heavens.

“Follow me,” she said, “I know a way,” and started down the garden at a run.

Presently we came to a wall the height of a man, beyond which was a thick hedge of aloes. Over the wall we climbed, and through the aloes we burst a path, not without doing ourselves some hurt,—for the thorns were sharp,—to find ourselves in a milpa or corn-field. Here the girl stopped, again searching the stars, and at that moment we heard sounds of shouting, and, looking back, saw lights moving to and fro in the hacienda.

“We must go forward or perish,” I said, “Don Pedro has aroused his men.”

Then she dashed into the milpa, and we followed her. There was no path, and the cornstalks, that stood high above us, caught our feet and shook the dew in showers upon our heads, till our clothes were filled with water like a sponge. Still we struggled on, one following the other, for fifteen minutes or more, till at length we were clear of the cultivated land and standing on the borders of the forest.

“Halt,” I said, “where do we run to? The road lies to the right, and by following it we may reach a town.”

“To be arrested as murderers,” broke in the señor. “You forget that José Moreno is dead at my hands, and his father will swear our lives away, or that at the best we shall be thrown into prison. No, no, we must hide in the bush.”

“Sirs,” said the old Indian, speaking for the first time, “I know a secret place in the forest, an ancient and ruined building, where we may take refuge for a while if we can reach it. But first I ask, who are you?”

“You should know me, Zibalbay,” said Molas, “seeing that I am the messenger whom you sent to search for him that you desire to find, the Lord and Keeper of the Heart,” and he pointed to me.

“Are you that man?” asked the Indian.

“I am,” I answered, “and I have suffered much to find you, but now is no time for talk; guide us to this hiding-place of yours, for our danger is great.”

Then once more the girl took the lead, and we plunged forward into the forest, often stumbling and falling in the darkness, till the dawn broke in the east, and the shoutings of our pursuers died away.