CHAPTER XIII.

IGNATIO’S OATH

AT sunrise on the following day I lit a fire by which to prepare soup for the señor, who still slept, and as I was engaged thus I saw the Lady Maya walking towards me, and noticed that her hands and feet were swollen.

“Señora,” I said, bowing before her, “I humbly congratulate you upon your courage and your escape from great dangers. Last night I said words to you in my grief that should not have been spoken, for it is my fault that I am apt to be unjust to women. I crave your pardon, and I will add that if, in atonement for my past injustice, I can serve you in any way now and afterwards, I pray you to command me.”

She listened and answered:

“I thank you for your kind words, Don Ignatio, and I forget other words that were not kind which you have spoken to me from time to time. If in truth you wish to show yourself my friend, it is in your power to do so. You have guessed my secret, therefore I am not ashamed to repeat that the señor yonder has become everything to me, though as yet I may be little to him. I ask you, then, to swear upon the Heart that you will do nothing to turn him from me, or to separate us should he ever learn to love me, but rather, should this come about, that whatever may be our need, you will help us by all means in your reach.”

“You ask me to swear a large oath, señora, and one that deals with the future, of which we have no knowledge,” I answered, hesitating.

“I do, señor, but remember that were it not for me at this moment your friend, who sleeps yonder like a child, would be stiff in death. Remember also that you have ends to gain in the City of the Heart, where it will be well for you to keep me as a friend should we ever live to reach it. Still, do not swear unless you wish, only then I shall know that you are my secret enemy and I shall be yours.”

“There is no need to threaten me, señora,” I answered, “nor am I to be moved thus, but I promise that I will not stand between you and the señor. Why should I? His will is his own, and, as you say, you saved his life. But see, he awakes, and his soup is ready.”

She took the pot off the fire, skimmed it, and poured the contents into a gourd.

“Shall I take it, or will you?” she asked.

“I think that you had better take it,” I answered.

Then she walked to the hammock and said, “Señor, here is your soup.”

He was but newly awakened, and looked at her vacantly.

“Tell me, Maya,” he asked, “what has happened?”

“Last evening,” she began, “in picking a flower for me you were bitten by a snake, and very nearly died.”

“I know,” he answered. “Without doubt I should have died had you not sucked the wound and tied a bandage round my wrist, for that grey snake is the deadliest in the country. Go on.”

“After the danger of the poison was past you became thirsty, so thirsty that you were dying of it, and there was no water to give you.”

“Yes, yes,” he said, “it was agony; I pray that I may never suffer so again. But I drank water and lived. Who brought it to me?”

“My father started on to the next camping-place, where there is a pool,” she answered.

“Has he returned?”

“No, not yet.”

“Then he cannot have brought the water. Where did it come from?”

“It came from the cueva, that cave which we examined before you were bitten.”

“Who went down the cueva to get it? The place is unclimbable.”

“I went down.”

“You!” he said, in amazement. “You! It is not possible. Do not jest. Tell me the truth quickly. I am tired.”

“I am not jesting. Listen, señor. You were dying for want of water, dying before our eyes; it was horrible to see. I could not bear it, and I knew that my father would not be back in time, so I took the water-skin and some torches and went without saying anything to Ignatio. The shaft was hard to climb, and the adventure strange. I will tell you of that by and by, but as it chanced I came through it safely to find Ignatio about to start on the same errand.”

The señor heard and understood, but he made no answer; he only stretched out his arms towards her, and there and thus in the wilderness did they plight their troth.

“Remember I am but an Indian girl,” she murmured presently, “and you are one of the white lords of the earth. Is it well that you should love me?”

“It is well,” he answered, “for you are the noblest woman that I have known, and you have saved my life.”

Zibalbay did not return till past midday, when he appeared with the water, leading the mule, which had set its foot upon a sharp stone in the desert and gone lame.

“Does he still live?” he asked of Maya.

“Yes, father.”

“He must be strong then,” he answered; “I thought that thirst would have killed him ere now.”

“He has had water, father. I descended the cueva and fetched it,” she added, after a moment’s pause.

The old man looked at her amazed.

“How came it that you found courage to go down that place, daughter?” he asked at length.

“The desire to save a friend gave me courage,” she answered, letting her eyes fall beneath his gaze. “I knew that you could not be back in time, so I went.”

Zibalbay pondered awhile, then said:

“I think that you would have done better to let him die, daughter, for I believe that this white man will bring trouble upon us. It has pleased the gods to preserve you alive; remember, then, that your life belongs to them, and that you must follow the path which they have chosen, not that which you would choose for yourself. Remember also that one waits you in the city yonder who may have a word to say as to your friendship with this wanderer.” And he passed on with the mule.

That same evening Maya told me of her father’s words and said:

“I think that before all is done I shall need the help that you have sworn to give me, señor, for I can see well that my father will be against me unless my wish runs with his purpose. Of one thing I am sure, that my life is my own and not a possession of the gods; for in such gods as my father worships and I was brought up to serve, I have lost faith, if indeed I ever had any.”

“You speak rashly,” I answered, “and if you are wise you will not let your father hear such words.”

“Lest by and by my life should be forfeit to the gods whom I blaspheme!” she broke in. “Say, then, do you believe in these gods, Don Ignatio?”

“No, Lady, I am a Christian and have no part with idols and those who worship them.”

“I understand; it is only in their wealth that you would have part. Well, and why should I not become a Christian also? I have learned something of your faith from the señor yonder, and see that it is great and pure, and full of comfort for us mortals.”

“May grace be given to you to follow in that road, Lady, but it is not Christian to taunt me about the wealth which I come to seek for the advantage of our race, seeing that you know I ask nothing for myself.”

“Forgive me,” she answered, “my tongue is sharp—as yours has been at times, Don Ignatio. Hark! the señor calls me.”

For two more days we rested there by the cueva till the señor was fit to travel, then we started on again. Ten days we journeyed across the wilderness, following the line of the ancient road, and meeting with no traces of man save such as were furnished by the familiar sight of ruined pyramids and temples. On the eleventh we began to ascend the slope of a lofty range of mountains that pushed its flanks far out into the desert-land, and on the twelfth we reached the snow-line, where we were obliged to abandon the three mules which remained to us, seeing that no green food was to be found higher up, and the path became too steep for them to find a footing on it. That night we slept, with little to eat, in a hole dug in the snow, wrapped in our serapes, or, rather, we tried to sleep, for our rest was broken by the cold, and the moaning of bitter and mysterious winds which sprang up and passed away suddenly beneath a clear sky; also, from time to time, by the thunder of distant avalanches rushing from the peaks above.

“How far must we travel up this snow?” I asked of Zibalbay, as we stood shivering in the ashy light of the dawn.

“Look yonder,” he answered, pointing to where the first ray of the sun shone upon a surface of black rock far above us; “there is the highest point, and we should reach it before nightfall.”

Thus encouraged we pushed forward for hour after hour, Zibalbay marching ahead in silence, until our sight was bewildered with snow-blindness, and I was seized with a fit of mountain sickness. Fortunately the climbing was not difficult, so that by four in the afternoon we found ourselves beneath the shadow of the wall of black rock.

“Must we scale that precipice?” I asked of Zibalbay.

“No,” he answered, “it would not be possible without wings. There is a way through it. Twice in the old days bodies of white men searching for the Golden City to sack it, came to this spot, but, finding no path through the cliff, they went home again, though their hands were on the door.”

“Does the wall of rock encircle all the valley of the city?” asked the señor.

“No, White Man, it ends many days’ journey away to the west, but he who would travel round it must wade through a great swamp. Also the mountains may be crossed to the east by journeying for three days through snows and down precipices; but so far as I have learned only one man lived to pass them, a wandering Indian, who found his way to the banks of the Holy Waters in the days of my grandfather. Now, stay here while I search.”

“Are you glad to see the gateway of your home, Maya?” asked the señor.

“No,” she answered, almost fiercely, “for here in the wilderness I have been happy, but there sorrow awaits me and you. Oh! if indeed I am dear to you, let us turn even now and fly together back to the lands where your people live,” and she clasped his hand and looked earnestly into his eyes.

“What,” he answered, “and leave your father and Ignatio to finish the journey by themselves?”

“You are more to me than my father, though perhaps this solemn Ignatio is more to you than I am.”

“No, Maya, but having come so far I wish to see the sacred city.”

“As you will,” she said, letting fall his hand. “See, my father has found the place and calls us.”

We walked on for about a hundred paces, threading our path through piles of boulders that lay at the foot of the precipice till we came to where Zibalbay stood, leaning against the wall of rock in which we could see no break or opening.

“Although I trust you, and, as I believe, Heaven has brought us together for its own purposes,” said the old cacique, “yet I must follow the ancient custom and obey my oath to suffer no stranger to see the entrance to this mountain gate. Come hither, daughter, and blindfold these foreigners.”

She obeyed, and as she tied the handkerchief about the señor’s face I heard her whisper,

“Fear not, I will be your eyes.”

Then we were taken by the hand, and led this way and that till we were confused. After we had walked some paces, we were halted and left while, as we judged from the sounds, our guides moved something heavy. Next we were conducted down a steep incline, through a passage so narrow and low that our shoulders rubbed the sides of it, and in parts we were obliged to bend our heads. At length, after taking many sharp turns, the passage grew wider and the path smooth and level.

“Loose the bandages,” said the voice of Zibalbay.

Maya did so, and, when our eyes were accustomed to the light, we looked round us curiously to find that we stood at the bottom of a deep cleft or volcanic rift in the rock, made not by the hand of man but by that of Nature working with her tools of fire and water. This cleft—along which ran a road so solidly built and drained that, save here and there where snowdrifts blocked it, it was still easily passable after centuries of disuse—did not measure more than forty paces from wall to wall. On either side of it towered sheer black cliffs, honeycombed with doorways that could only have been reached by ladders.

“What are those?” I asked of Zibalbay. “Burying-places?”

“No,” he answered, “dwelling-houses. They were there, so say the records, before our forefathers founded the City of the Heart, and in them dwelt cave-men, barbarians who fed on little and did not feel the cold. It was by following some of these cave-men through that passage which we have passed that the founder of the ancient city discovered this cleft and the good country and great lake that lie beyond it, where the rock-dwellers, whom our forefathers killed out, used to live in the winter season. Once, when I was young, with some companions I entered these caves by means of ropes and ladders, and found many strange things there, such as stone axes and rude ornaments of gold, relics of the barbarians. But let us press on, or night will overtake us in the pass.”

By degrees the great cleft, that had widened as we walked, began to narrow again till it appeared to end in a second wall of rock.

Passing round a boulder that lay at the foot of this wall, Zibalbay led the way into a tunnel behind it.

“Do not fear the darkness,” he said, “the passage is short and there are no pitfalls.”

So we followed the sound of his footsteps through the gloom, till presently a spot of light appeared before us, and in another minute we stood on the further side of the mountain, though we could see nothing of the place because of the falling shadows.

Without pausing, Zibalbay pushed on down the hill, and, suddenly turning to the right, stopped before the door of a house built of hewn stone.

“Enter,” he said, “and welcome to the country of the People of the Heart.”

As the door was thrown open, light from the fire within streamed through it, and a man’s voice was heard asking, “Who is there?”

Without answering, Zibalbay walked into the room. It was a low vaulted apartment, and at a table placed before the great fire which burnt upon the hearth sat a man and a woman eating.

“Is this the way that you watch for my return?” he asked in a stern voice. “Haste now and make food ready for we are starved with cold and hunger.”

The man, who had risen, stood hesitating, but the woman, whose position enabled her to see the face of the speaker, caught him by the arm, saying,

“Down to your knees, husband. It is the cacique come back.”

“Pardon,” cried the man, taking the hint; “but to be frank, O lord, it has been so dinned in my ears down in the city yonder, that neither you nor the Lady of the Heart would ever return again, that I thought you must be ghosts. Yes, and so they will think in the city, where I have heard that Tikal rules in your place.”

“Peace,” said Zibalbay, frowning heavily. “We left robes here, did we not? Go, lay them out in the sleeping-chambers, and with them others for these my guests, while the woman prepares our meat.”

The man bowed, stretching out his arms till the backs of his hands touched the ground. Then, taking an earthenware lamp from a side table, he lit it and disappeared behind a curtain, an example which the woman followed after she had rapidly removed the dishes that were upon the table, and fed the fire with wood.

When they were gone we gathered round the hearth to bask in the luxury of its warmth.

“What is this place?” asked the señor.

Zibalbay, who was wrapped in his own thoughts, did not seem to hear him, and Maya answered,

“A poor hovel that is used as a rest-house and by hunters of game, no more. These people are its keepers, and were charged to watch for our return, but they seem to have fulfilled their task ill. Pardon me, I go to help them. Come, father.”

They went, and presently the señor awoke from a doze induced by the delightful warmth of the fire, to see the custodian of the place standing before him staring at him in amazement not unmixed with awe.

“What is the matter with the man, and what does he want, Ignatio?” he asked in Spanish.

“He wonders at your white skin and fair hair, señor, and says that he does not dare to speak to you because you must be one of the Heaven-born of whom their legends tell, wherefore he asks me to say that water to wash in and raiment to put on have been made ready for us if we will come with him.”

Accordingly we followed the Indian, who led us into a passage at the back of the sitting-chamber, and thence to a small sleeping-room, one of several to which the passage gave access. In this room, which was lit by an oil lamp, were two bedsteads covered with blankets of deerskin and cotton sheets, and laid upon them were fine linen robes, and serapes made in alternate bands of grey and black feathers, worked on to a foundation of stout linen. Standing upon wooden stools in a corner of the room, and half-filled with steaming water, were two basins, which the señor noticed with astonishment were of hammered silver.

“These people must be rich,” he said to me so soon as the keeper of the place had gone, “if they fashion the utensils of their rest-houses of silver. Till now this story of the Sacred City of which Zibalbay was cacique, and Maya heiress apparent, has always sounded like a fairy tale to me, but it seems that it is true after all, for the man’s manner shows that Zibalbay is a very important person.”

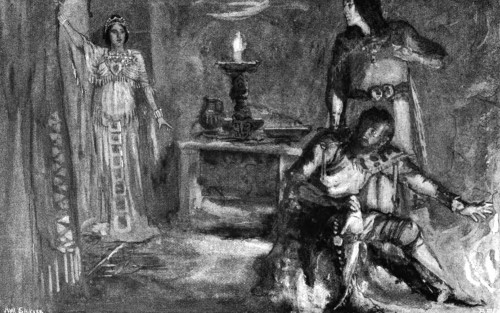

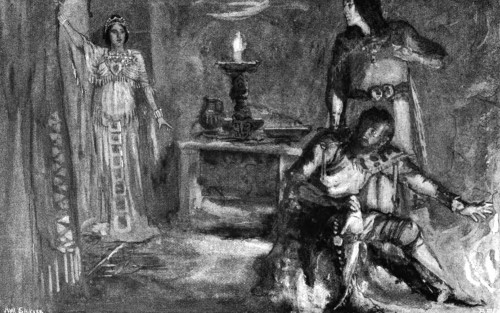

Then we put on the robes that had been provided for our use, not without difficulty, since their make was strange to us, and returned to the eating-room. Presently the curtain was drawn, and the Lady Maya joined us—the Lady Maya, but so changed that we started in astonishment.

Presently the curtain was drawn, and the Lady Maya joined us.

Different, indeed, was she to the ill-clad and travel-stained girl who had been our companion for so many weeks. Now she was dressed in a robe of snowy white, bordered with embroidery of the royal green, and having the image of the Heart traced in gold thread upon the breast. On her feet were sandals, also worked in green, while round her throat, wrists, waist, and ankles shone circlets of dead gold. Her dark hair no longer fell loose about her, but was twisted into a simple knot and confined in a little golden net, and from her shoulders hung a cloak of pure white feathers, relieved here and there by the delicate yellow plumes of the greater egret.

“Like you I have changed my garments,” she said in explanation. “Is the dress ugly, that you look astonished?”

“Ugly!” answered the señor, “I think it is the most beautiful that I ever saw.”

“This is the most beautiful dress that you ever saw! Why, friend, it is the simplest that I have. Wait till you see me in my royal robes, wearing the great emeralds of the Heart; what will you say then, I wonder?”

“I cannot tell, but I say now that I don’t know which is the most lovely, you or your dress.”

“Hush!” she said, laughing, yet with a note of earnestness in her voice. “You must not speak thus freely to me. Yonder in the pass, friend, I was the Indian girl your fellow-traveller; here I am the Lady of the Heart.”

“Then I wish that you had remained the Indian girl in the pass,” he answered, after a pause, “but perhaps you jest.”

“I was not altogether jesting,” she answered, with a sigh, “you must be careful now, or it might be ill for you or me, or both of us, since by rank I am the greatest lady in this land, and doubtless my cousin, Tikal, will watch me closely. See! here comes my father.”

As she spoke Zibalbay entered, followed by the two Indians bearing food. He was simply dressed in a white toga-like robe similar to that which had been given to the señor and myself. A cloak of black feathers covered his shoulders, and round his neck was hung a massive gold chain to which was attached the emblem of the Heart, also fashioned in plain gold.

We noticed that, as he came, his daughter, Maya, made a courtesy to him, which he acknowledged with a nod, and that whenever they passed him the two Indians crouched almost to the ground.

Evidently the friendship of our desert journeying was done with, and the person of whom we had hitherto thought and spoken as an equal must henceforth be treated with respect. Indeed the proud-faced, white-bearded chief seemed so royal in his changed surroundings that we were almost moved to follow the example of the others, and bow whenever he looked at us.

“The food is ready,” said Zibalbay, “such as it is. Be seated, I beg of you. Nay, daughter, you need not stand before me. We are still fellow-wanderers, all of us, and ceremony can stay till we are come to the City of the Heart.”

Then we sat down and the Indians waited on us. What the dishes consisted of we did not know, but after our long privations it seemed to us that we had never eaten so excellent a meal, or drunk anything so good as the native wine which was served with it. Still, notwithstanding our present comfort, I think the señor’s heart misgave him, and that he had presentiments of evil. Maya and he still loved one another, but he felt that things were utterly changed, as she herself had shown him. While they wandered, in some sense he had been the head of the party, as, to speak truth, among companions of a coloured race a white man of gentle birth is always acknowledged to be by right of blood. Now things were changed, and he must take his place as an alien wanderer, admitted to the country upon sufferance, and already this difference could be seen in Zibalbay’s manner and mode of address. Formerly he had called him “señor,” or even “friend;” to-night, when speaking to him, he used a word which meant “foreigner,” or “unknown one,” and even myself he addressed by name without adding any title of respect.

One good thing, however, we found in this place, who had lacked tobacco for six weeks and more, for presently the Indian entered bearing cigarettes made by rolling the herb in the thin sheath that grows about the cobs of Indian corn.

“Come hither, you,” said Zibalbay to the Indian, when he had handed us the cigarettes. “Start now to the borders of the lake and advise the captain of the village of the corn-growers that his lord is returned again, commanding him in my name to furnish four travelling litters to be here within five hours after sunrise. Warn him also to have canoes in readiness to bear us across the lake, but, as he values his life, to send no word of our coming to the city. Go now and swiftly.”

The man bowed, and, snatching a spear and a feather cloak from a peg near the door, vanished into the night, heedless of the howling wind and the sleet that thrashed upon the roof.

“How far is it to the village?” asked the señor.

“Ten leagues or more,” Zibalbay answered, “and the road is not good, still if he does not fall from a precipice or lose his life in a snow-drift, he will be there within six hours. Come, daughter, it is time for us to rest, our journey has been long, and you must be weary. Good night to you, my guests, to-morrow I shall hope to house you better.” Then, bowing to us, he left the room.

Maya rose to follow his example, and, going to the señor, gave him her hand, which he touched with his lips.

“How good it is to taste tobacco again,” he said as Maya went. “No, don’t go to bed yet, Ignatio, take a cigarette and another glass of this agua ardiente, and let us talk. Do you know, friend, it seems to me that Zibalbay has changed. I never was a great admirer of his character, but perhaps I do not understand it.”

“Do you not, señor? I think that I do. Like some Christian priests the man is a fanatic, and like myself, a dreamer. Also he is full of ambition and tyrannical, one who will spare neither himself nor others where he has an end to gain, or thinks that he can promote the welfare of his country and the glory of his gods. Think how brave and earnest the man must have been who, at the bidding of a voice or a vision, dared in his old age, unaccompanied save by his only child, to lay down his state and travel almost without food through hundreds of leagues of bush and desert, that none of his race had crossed for generations. Think what it must have been to him who for many years has been treated almost as divine, to play the part of a medicine-man in the forests of Yucatan, and to suffer, in his own person and in that of his daughter, insults and torment at the hands of low white thieves. Yet all this and more Zibalbay has borne without a murmur because, as he believes, the object of his mission is attained.”

“But, Ignatio, what is the object of his mission, and what have we to do with it? To this hour I do not quite know.”

“The object of his mission, and indeed of his life, is to build up the fallen empire of the City of the Heart. In short, señor, though I do not believe in his gods, in Zibalbay’s visions I do believe, seeing that they have led him to me, whose aim is his aim, and that neither of us can succeed without the other.”

“Why not?”

“Because I need wealth and he needs men; and if he will give me the wealth, I can give him men in thousands.”

“I hear,” answered the señor. “It sounds simple enough, but perhaps you will both of you find that there are difficulties in the way. What I do not understand, however, is what part Maya and I are to play in this affair, who are not anxious to regenerate a race or to build up an empire. I suppose that we are only spectators of the game.”

“How can that be, señor, when she is Lady of the Heart and heiress to her father, and when,” I added, dropping my voice, “you and she have grown so dear to one another?”

“I did not know that you had noticed anything of that, Ignatio. You never seemed to observe our affection, and, as you hate women so much, I did not speak of it,” he answered, colouring.

“I am not altogether blind, señor. Also, is it possible for a man not to know when a woman comes between him and the friend he loves? But of that I will say nothing, for it is as it should be; besides, you might scarcely understand me if I did. No, no, señor, you cannot be left out of this game, you are too deep in it already, though what part you will play I cannot tell. It depends, perhaps, upon what the gods reveal to Zibalbay, or what he guesses that they reveal. At present he is well disposed towards you because he thinks that the oracle may declare you to be the son of Quetzal through whom his people shall be redeemed, since it seems that here there is some such prophecy, and for this reason it is that he has not forbidden the friendship between you and his daughter, or so he hinted to me. But be warned, señor; for if he comes to know that you are not the man, then he will sweep you aside as of small account, and you may bid farewell to the Lady of the Heart.”

“I will not do that while I live,” he answered quietly.

“No, señor, perhaps not while you live, but those who stand in the path of priests and kings do not live long. Still, though there is cause to be cautious, there is no cause to be down-hearted, seeing that if you are not the man, I may be, in which case I shall be able to help you, as I have sworn to the Lady Maya that I will do, or perhaps you will be able to help me.”

“At any rate, we will stand together,” said the señor. “And now, as there is no use in talking of the future, I think that we had better go to sleep. Of one thing, however, you may be certain—unless she dies, or I die, I mean to marry Maya.”