CHAPTER XV.

HOW ZIBALBAY CAME HOME

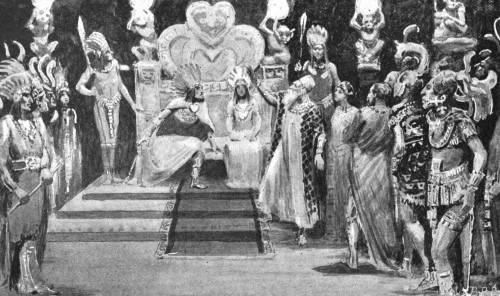

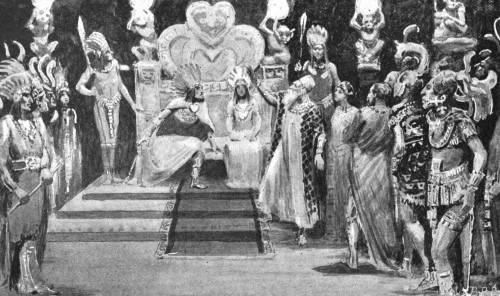

FOR a while we stood unnoticed in the shadow of the doorway, observing this strange and beautiful scene, till, as Zibalbay was about to advance towards the throne, the Lord Tikal held up his sceptre as a signal, and suddenly the women ceased from their dance and song. At the sight of the uplifted sceptre, Zibalbay halted again and drew back further into the shadow, motioning us to do likewise. Then Tikal began to speak in a rich, deep voice that filled the hall:

“Councillors and Nobles of the Heart,” he said, “and you, high-born ladies, wives and daughters of the nobles, hear me. But yesterday, as you know, I took upon myself the place and power of my forefathers, and by your wish and will I was proclaimed the sole chief and ruler of the People of the Heart. Now I have bidden you to my marriage feast, that you may grace my nuptials and share my joy. For be it known to you that to-night I have taken in marriage Nahua the Beautiful, daughter of the High Lord Mattai, Chief of the Astronomers, Keeper of the Sanctuary, and President of the Council of the Heart. Her, in the presence of you all, I name as my first and lawful wife, the sharer of my power, and your ruler under me, who, whate’er betide, cannot be put away from my bed and throne, and as such I call upon you to salute her.”

Then, ceasing from his address, he turned and kissed the woman at his side, saying:

“Hail! to you, Lady of the Heart, whom it has pleased the gods to lift up and bless. May children be given to you, and with them happiness and power for many years.”

Thereon the whole company bowed themselves before Nahua, whose fair face flushed with pride and joy, and repeated, as with one voice:

“Hail! to you, Lady of the Heart, whom it has pleased the gods to lift up and bless. May children be given to you, and with them happiness and power for many years.”

“Nobles,” went on Tikal, when this ceremony was finished, “it has come to my ears that there are some who murmur against me, saying that I have no right to the ancient sceptre of cacique which I hold in my hand this night. Nobles, I have somewhat to say to you of this matter, that to-morrow, after the sacrifice, I shall repeat in the ears of the common people, and I say it having consulted with my Council, the masters of the mysteries of the Heart. To-morrow a year will have gone by since Zibalbay, my uncle, who was cacique before me, and his only child and heiress of his rank and power, the Lady Maya, my affianced bride, left the city upon a certain mission. Before they departed upon this mission, it was agreed between Zibalbay, Maya, the Lady of the Heart, myself, and the Council, the Brotherhood of the Heart, that I should rule as next heir during the absence of Zibalbay and his daughter, and that if they should not return within two years, then their heritage should be mine for ever. To this agreement I set my name with sorrow, for then, as now, I held that my uncle was mad, and in his madness went to doom, taking with him his daughter whom I loved. Yet when they were gone I fulfilled it to the letter; but trouble arose among the people, for they will not listen to the voice of one who is not their anointed lord, but say, ‘We will wait until Zibalbay comes again and hear his command upon these matters.’

“Also, Zibalbay being absent, there was no high priest left in the land, so that until a successor was raised up to him, certain of the inmost mysteries of our worship must go uncelebrated, thus bringing down upon us the anger of the Nameless god. So it came about that many pressed it on me that for the sake of the people and the welfare of the city, I should shorten the period of my regency and suffer myself to be anointed. But, remembering my promise, I answered them sharply, saying that I would not depart from it by a hair’s breadth, and that, come what might, two full years must be completed before I sat me down in the place of my fathers.

“To this mind, then, I held till three days since, when those of the people to whose lot it fell in turn to pass to the mainland, there to cultivate the fields that are apportioned to the service of the temple, refused to get them to their labour, declaring that the high priest alone had authority over them, and there was no high priest in the city. Then in my perplexity I took counsel with the Lord Mattai, Master of the Stars, and he consulted the stars on my behalf. All night long he searched the heavens, and he read in them that Zibalbay, who, led by a lying dream, broke through the laws of the land and wandered across the mountains, has paid the price of his folly, and is dead in the wilderness, together with his daughter that was my affianced and the Lady of the Heart. Is it not so, Mattai?”

Now the person addressed, a stout man with a bald head, quick, shifting eyes, and a thick and grizzled beard, stepped forward and said, bowing,

“If my wisdom is not at fault, such was the message of the stars, O lord.”

“Nobles,” went on Tikal, “you have heard my testimony and the testimony of Mattai, whose voice is the voice of truth. For these reasons I have suffered myself to be anointed and set over you as your ruler, seeing that I am the heir of Zibalbay by law and by descent. For these reasons also—she to whom I was affianced being dead—I have taken to wife Nahua the daughter of Mattai. Say, do you accept us?”

Some few of the company were silent, but the rest cried:

“We accept you, Tikal and Nahua, and long may you rule over us according to the ancient customs of the land.”

“It is well, my brethren,” answered Tikal. “Now, before we drink the parting-cup, have any of you ought to say to me?”

“I have something to say to you,” cried Zibalbay in a loud voice from the shadows wherein we stood at the far end of the hall.

At the sound of his voice, the tones of which he seemed to know, Tikal started and rose in fear, but, recovering himself, said:

“Advance from the shadow, whoever you are, and say your say where men may see you.”

Turning to his daughter and to us, Zibalbay bade us follow him, and do as he did. Then, veiling his face with a corner of his robe, he walked up the hall, the crowd of nobles and ladies opening a path till we stood before the throne. Here he uncovered himself, as we did also, and standing sideways, so that he could be seen both by Tikal and all that company, he opened his lips to speak. Before a word could pass them a cry of astonishment broke from the nobles, and of a sudden the sceptre fell from the hand of Tikal and rolled along the floor.

“Zibalbay!” said the cry. “It is Zibalbay come back, or the ghost of him, and with him the Lady of the Heart!”

“Aye, nobles,” he said, in a quiet voice, although his hand shook with rage, “it is I, Zibalbay, your lord, come home, and not too soon, as it would seem. What, my nephew, were you so hungry for my place and power, that you must break the oath you swore upon the Heart, and seize them before the appointed time? And you, Mattai, have you lost your skill, or have the gods smitten you with a curse, that you prophesy falsely, saying that it was written in the stars that we who are alive were dead, thereby lifting up your daughter to the seat of the Lady of the Heart. Nay, do not answer me. Standing yonder I have heard all your story. I say to you, Tikal, that you are a foresworn traitor, and to you, Mattai, that you are a charlatan and a liar, who have dared to use the holy art for your own ends, and the advancement of your house. On both of you will I be avenged,—aye, and on all those who have abetted you in your crimes. Guards, seize that man, and the Lord Mattai with him, and let them be held fast till I shall judge them.”

‘It is I, Zibalbay, your lord, come home.’

Now the soldiers that stood on either side of the thrones hesitated for a moment, and then advanced towards Tikal as though to lay hands upon him in obedience to Zibalbay’s order. But Nahua rose and waved them off, saying:

“What! dare you to touch your anointed lord? Back, I say to you, if you would save yourselves from the doom of sacrilege. Living or dead, the day of Zibalbay is done, for the Council of the Heart has set his crown upon the brow of Tikal, and, whether for good or ill, their decree cannot be changed.”

“Aye!” said Tikal, whose courage had come back to him. “The Lady Nahua speaks truth. Touch me not if you would live to look upon the sun.”

But all the while he spoke his eyes were fixed upon Maya, whose beautiful face he watched as though it were that of some lost love risen from the dead.

Now, as Zibalbay was about to speak again, Mattai the astronomer bowed before him and said:

“Be not angry, but hear me, my lord. You have travelled far, and you are weary, and a weary man is apt at wrath. You think that you have been wronged, and, doubtless, all this that has chanced is strange to you, but now is not the time for us to give count of our acts and stewardship, or for you to hearken. Rest this night; and to-morrow on the pyramid, in the presence of the people, all things shall be made clear to you, and justice be done to all. Welcome to you, Zibalbay, and to you also, Daughter of the Heart,—and say, who are these strangers that you bring with you from the desert lands across the mountains?”

Zibalbay paused awhile, looking round him out of the corners of his eyes, like a wolf in a trap, for he sought to discover the temper of the nobles. Then, finding that there were but few present whom he could trust to help him, he lifted his head and answered:

“You are right, Mattai, I am weary; for age, travel, and the faithlessness of men have worn me out. To-morrow these matters shall be dealt with in the presence of the people, and there, before the altar, it shall be made known whether I am their lord, or you, Tikal. There, too, I will tell you who these strangers are, and why I have brought them across the mountains. Until then I leave them in your keeping, for your own sake charging you to keep them well. Nay, here I will neither eat nor drink. Do you come with me,” and he called to certain lords by name whom he knew to be faithful to him.

Then, without more words, he turned and left the hall, followed by a number of the nobles.

“It seems that my father has forgotten me,” said Maya, with a laugh, when he had gone. “Greeting to you all, friends, and to you, my cousin, Tikal, and greeting also to your wife, Nahua, who, once my waiting-lady, by the gift of fortune has now been lifted up to take my place and title. Whatever may be the issue of these broils, may you be happy in each other’s love, Tikal and Nahua.”

Now Tikal descended from the throne and bowed before her, saying, “I swear to you, Maya——”

“No, do not swear,” she broke in, “but give me and my friends here a cup of wine and some fragments from your wedding-feast, for we are hungry. I thank you. How beautiful is that bride’s robe which Nahua wears, and—surely—those emeralds were once my own. Well, let her take them from me as a wedding-gift. Make room, I pray you, Tikal, and suffer these ladies to tell me of their tidings, for remember that I have wandered far, and it is pleasant to see faces that are dear to me.”

For awhile we sat and ate, or made pretence to eat, while Maya talked thus lightly and all that company watched us, for we were wonderful in their eyes, who never till now had seen a white man. Indeed, the sight of the señor, auburn-haired, long-bearded, and white-skinned, was so marvellous to them, that, unlike the common people, they forgot their courtesy and crowded round him in their amazement. Still, there were two who took small note of the señor or of me, and these were Tikal, who gazed at Maya as he stood behind her chair serving her like some waiting slave, and Nahua his wife, who sat silent and neglected on her throne, sullenly noting his every word and gesture. At length she could bear this play no longer, but, rising from her seat, began to move down the chamber.

“Make room for the bride, ladies,” said Maya. “Cousin, good-night, it grows late, and your wife awaits you.”

Then, muttering I know not what, Tikal turned and went, and side by side the pair walked down the great hall, followed by their guard of soldiers.

“How beautiful is the bride, and how brave the groom!” said Maya, as she watched them go, “and yet I have seen couples that looked happier on their wedding-day. Well, it is time to rest. Friends, good-night. Mattai, I leave these strangers in your keeping. Guard them well—and, stay, bring them to my apartments to-morrow after they have eaten, for if it is my father’s will, I would show them something of the city before the hour of noon, when we meet upon the temple-top.”

When she had gone, Mattai bowed to us with much ceremony and begged us to follow him, which we did, across the courtyard and through many passages, to a beautiful chamber, dimly lighted with silver lamps, that had been made ready for us. Here were beds covered with silken wrappings, and on a table in the centre of the room cool drinks and many sorts of fruits, but so tired were we that we took little note of these things.

Bidding good-night to Mattai, who looked at us curiously and announced that he would visit us early in the morning, we made fast the copper bolts upon the door and threw ourselves upon the beds.

Weary as I was, I could not sleep in this strange place, and when, from time to time, my eyes closed, the sound of feet passing without our chamber door roused me again to wakefulness. Of one thing I was sure, that Zibalbay was not wanted here in his own city, and that there would be trouble on the morrow when he told his tale to the people, for certainly Tikal would not suffer himself easily to be thrust from the place he had usurped, and he had many friends. Doubtless it was their feet that I heard outside the door as they hurried to and fro from the chamber where Mattai sat taking counsel with them. What would be our fate, I wondered, in this struggle for power that must come? These people feared strangers—so much I could read in their faces—and doubtless they would be rid of us if they might. Well, we had a good friend in Maya, and the rest we must leave to Providence.

Thinking thus, at length I fell asleep, to be awakened by the voice of the señor, who was sitting upon the edge of his bed, singing a song and looking round the chamber, for now the daylight streamed through the lattices. I wished him good-morrow, and asked him why he sang.

“Because of the lightness of my heart,” he answered. “We have reached the city at last, and it is far more splendid and wonderful than anything I dreamed of. Also the luck is with us, for this Tikal has taken another woman in marriage, who, to judge from the look of her, will not readily let him go, and therefore Maya has no more to fear from him. Thirdly, there is enough treasure in this town, if what we saw last night may be taken as a sample, to enable you to establish three Indian Empires, if you wish, and doubtless Zibalbay will give you as much of it as you may want. Therefore, friend Ignatio, you should sing, as I do, instead of looking as gloomy as though you saw your own coffin being brought in at the door.”

I shook my head, and answered:

“I fear you speak lightly. There is trouble brewing in this city, and we shall be drawn into it, for the struggle between Tikal and Zibalbay will be to the death. As for the Lady Maya, of this I am certain, that—wife or no wife—Tikal still loves her and will strive to take her; I saw it in his eyes last night. Lastly, it is true enough that here there is boundless wealth; but whether its owners will suffer me to have any portion of it, to forward my great purposes,—useless though it be to them,—is another matter.”

“There was a man in the Bible called Job, and he had a friend named Eliphaz,—I think you are that friend come to life again, Ignatio,” answered the señor, laughing. “For my part, I mean to make the best of the present, and not to trouble myself about the future or the politics of this benighted people. But hark, there is someone knocking at the door.”

I rose, and undid the bolt, whereon attendants entered bearing goblets of chocolate, and little cakes upon a tray. After we had eaten, they led us to the baths, which were of marble and very beautiful, one of them being filled with water from a warm spring, and then to a chamber, where breakfast was made ready for us. While we sat at table, Mattai came to us, and I saw that he had not slept that night, for his eyes were heavy.

“I trust that you have rested well, strangers,” he said courteously.

“Yes, lord,” I answered.

“Well, it is more than I have done, for it is my business to watch the stars, especially my own star, which just now is somewhat obscured,” and he smiled. “If you have finished your meal, my commands are to lead you to the apartments of the Lady Maya, who wishes to show you something of our city, which, being strangers, may interest you. By the way, if I do not ask too much, perhaps you will tell me to what race you belong,” and he bowed towards the señor. “We have heard of white men here, though we have learned no good of them, and tradition tells us that our first ruler, Cucumatz, was of this race. Are you of his blood, stranger?”

“I do not know,” answered the señor, laughing. “I come from a cold country far beyond the sea, where all the men are as I am.”

“Then the inhabitants of that country must be goodly to behold,” answered Mattai gravely. “I thank you for your courtesy, Son of the Sea, in answering my question so readily. I did not ask it from curiosity alone, since the people in this city are terrified of strangers, and clamour for some account of you.”

“Doubtless our friend Zibalbay will satisfy them,” I said.

“Good. Now be pleased to follow me,”—and Mattai led us across courts and through passages till we reached a little ante-room filled with ancient carvings and decorated with flowers, where some girls stood chatting.

“Tell the Lady Maya that her guests await her,” said Mattai, then turned to take his departure, adding, in a low voice, “doubtless we shall meet at noon upon the pyramid, and there you will see I know not what; but, whatever befalls, be sure of this, strangers, that I will protect you if I can. Farewell.”

One of the girls vanished through a doorway at the further end of the chamber, and, having offered us seats, the others stood together at a little distance, watching us out of the corners of their eyes. Presently the door opened, and through it came Maya, wearing a silken serape that covered her head and shoulders and looking very sweet and beautiful in the shaded light of the room.

“Greeting, friends,” she said, as we bowed before her. “I have my father’s leave to show you something of this city that you longed so much to see. These ladies here will accompany us, and a guard, but we shall want no litters until we have ascended the great temple, for I desire that you should see the view from thence before the place is cumbered with the multitude. Come, if you are ready.”

Accordingly we set out, Maya walking between us, while her guards and ladies followed after. Crossing the square, which had been the scene of the festival of the previous night, but now in the early morning was almost deserted, we came to the inclosure of the court-yard of the pyramid, a limestone wall worked with sculptures of hunting scenes, relieved by a border of writhing snakes, and at intervals by emblems of the Heart. At the gateway of this wall we paused to contemplate the mighty mass of the pyramid that towered above us. There is one in the land of Egypt that is bigger, so said the señor, although he believed this to be a more wonderful sight because of its glittering slopes of limestone, whose expanse was broken only by the vast stair that ran up its eastern face from base to summit.

“It is a great building,” said Maya, noting our astonishment, “and one that could not be reared in these days. Tradition says that five-and-twenty thousand men worked on it for fifty years—twenty thousand of them cutting and carrying the stone, and five thousand laying the blocks.”

“Where did the material come from, then?” asked the señor.

“Some of it was hewn from beneath the base of the temple itself,” she answered, “but the most was borne in big canoes from quarries on the mainland, for these quarries can still be seen.”

“Is the pyramid hollow, then?” I asked.

“Yes, in it are many chambers, for the most part store and treasure houses, and beneath its base lie crypts, the burying-place of the caciques, their wives, and children. There also is the Holy Sanctuary of the Heart, which you, being of the Brotherhood, may perhaps be permitted to visit. Come, let us climb the stair,”—and she led us across the court-yard to the foot of a stairway forty feet or more in breadth, which ran to the platform of the pyramid in six flights, each of fifty steps, and linked together by resting-places.

Up these flights we toiled slowly, followed by the ladies and the guard, till at length our labour was rewarded, and we stood upon the dizzy edge of the pyramid. Before us was a platform bordered by a low wall, large enough to give standing room to several thousand people. On the western side of this platform stood a small marble house, used as a place to store fuel, and as a watch-tower by the priests, who were on duty day and night, tending the sacred fire which flared in a brazier from its roof. Situated at some distance from this house, and immediately in front of it, was a small altar wreathed with flowers, but for the rest the area was empty.

“Look,” said Maya.

The city beneath us was built upon a low, heart-shaped island, so hollow in its centre that once it might have been the crater of some volcano, or perhaps a mere ridge of land inclosing a lagoon. This island measured about ten miles in length by six across at its widest, and seemed to float like a huge green leaf upon the lake, the Holy Waters of these Indians, of which the circumference is so great that even from the summit of the pyramid, a few small and rocky islets excepted, land was only visible to the north, whence we had sailed on the previous night. Elsewhere the eye met nothing but blue expanses of inland sea, limitless and desolate, unrelieved by any sail or sign of life. Amidst these waters the island gleamed like an emerald. Here were gardens filled with gorgeous flowers and clumps of beautiful palms and willows, framed by banks of dense green reeds that grew in the shallows around the shores. So luxuriant was the vegetation, fertilised year by year with the rich mud of the lake, and so lovely were the trees and flowers in the soft light of the morning, that the place seemed like a paradise rather than a home of men; and as was the island, so was the city that was built upon one end of it.

Following the lines of the land upon which it stood, it was heart-shaped—a heart of cold, white marble lying within a heart of glowing green. All about it ran a moat filled with water from the lake, and on the hither side of this moat stood a wall fifty feet or more in height, built of great blocks of white limestone that formed the bed-rock of the island, which wall was everywhere sculptured with allegorical devices and designs, and the gigantic figures of gods. Within the oblong of this wall lay the city; a city of palaces, pyramids, and temples, or rather the remains of it, for we could see at a glance that the population was unable to keep so many streets and edifices in repair. Thus palm-trees were to be found growing through the flat roofs of houses, and in crevices of the temple-pyramids, while many of the streets and avenues were green with grass and ferns, a narrow pathway in the centre of them showing how few were the feet of the passers-by. Even in the great square beneath us the signs of traffic were rare, and there was little of the bustle of a people engaged in the business of life, although this very place had been the scene of last night’s feast, and would again soon be filled with men and women flocking to the pyramid. Now and again some graceful, languid girl, a reed basket in her hand, might be seen visiting the booths, where rations of fish from the lake, or of meal, fruit, dried venison, and cocoa, were distributed according to the wants of each family. Or perhaps a party of men, on their way to labour in the gardens, stopped to smoke and talk together in a fashion that showed time to be of little value to them. Here and there also a few—a very few—children played together with flowers for toys in the shadow of the palaces, barracks, and store-houses which bordered the central square; but this was all, for the rest the place seemed empty and asleep.