CHAPTER II

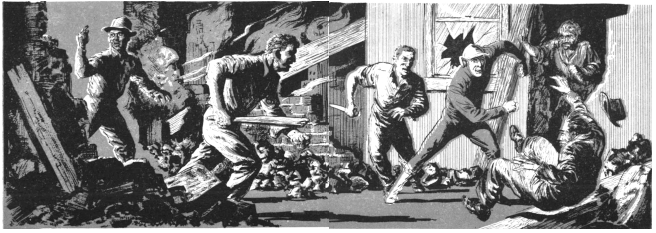

It was the very number of Wales' attackers that saved him. There were too many of them, they were too eager to get at him. As he hit the pavement, they dropped their flashlights and crowded around in the dark, getting in each other's way, like frantic dogs chivvying a small animal.

A foot trampled his shoulder and he rolled away from it. All around him in the dark were trousered legs, stumbling over him. Voices yelled, "Where is he?" They yelled, "Bring the lights!"

The lights, if they came, would mean his death. A mob, even a small mob like this one, was a mindless animal. Wales, floundering amid the dark legs, kept his head. He shouted loudly,

"Here come the Evacuation trucks—here they come! We'd better beat it!"

He didn't think it would work, but it did. In that noisy, scuffling darkness, no one could tell who had shouted. And these people were already alarmed.

The legs around him shifted and stamped and ran away over the pavement. A woman screeched thinly in fear. He was alone in the dark.

He didn't think he would be left alone for long. He started to scramble to his feet, beside the curb, and his hand went into an opening—a long curbside storm-sewer drain.

A building was what he had had in mind, but this was better. He got down on his belly and wormed sidewise into the drain. He lay quiet, in a concrete cave smelling of old mud.

Feet came pounding back along the streets, he glimpsed beams of light angling and flickering. Angry voices yelled back and forth. "He's not here. He's got away. But there must be other goddamned Evacuation men around. They're going to round us up—"

"By God, nobody's going to round me up and take me to Mars!" said a deep bass voice right beside Wales.

Somebody else said, "All that nonsense about Kendrick's World—" and added an oath.

Wales lay still in his concrete hole, nursing his bruised shoulder. He heard them going away.

He waited, and then crawled out. In the dark street, he stood, muddy and bruised, conscious now that he was shaking.

What in the world had come over these people? At first, five years ago, it had been difficult to convince many that an errant asteroid would indeed ultimately crash into Earth. Kendrick's first announcement had been disbelieved by many.

But when all the triple-checking by the world's scientists had confirmed it, the big campaign of indoctrination that the UN put on had left few skeptics. Wales himself remembered how every medium of communication had been employed.

"Earth will not be destroyed," the UN speakers had repeated over and over. "But it will be made uninhabitable for a long time. The asteroid Nereus will, when it collides, generate such a heat and shock wave that nothing living can survive it. It will take many years for Earth's surface to quiet again after the catastrophe. Men—all men—must live on Mars for perhaps a whole generation."

People had believed. They had been thankful then that they had a way of escape from the oncoming catastrophe—that the colonization of Mars had proceeded far enough that it could serve as a sanctuary for man, and that modern manufacture of synthetic food and water from any raw rock would make possible feeding all Earth's millions out on that arid world.

They had toiled wholeheartedly at the colossal crash program of Operation Doomsday, the building of the vast fleet of rocket-ship transports, the construction and shipping out of the materials for the great new prefab Martian cities. They had, by the tens and hundreds of millions, gone in their scheduled order to the spaceports and the silver ships that took them away.

But now, with millions still left on Earth, there was a change. Now skepticism and rebellion against Evacuation were breeding here on Earth.

It didn't, Wales thought, make sense!

He was suddenly very anxious to reach New York, to see Fairlie.

He went back along the dark street to the main boulevard, where the little white route signs glimmered faintly. He looked for the car, but did not see it.

Shrugging, Wales started along the highway. He couldn't be too far from the big Evacuation Thruways.

He had gone only a few blocks in the dark, when lights suddenly came on and outlined him. He whirled, startled.

"Mr. Wales," said a voice.

Wales relaxed. He walked toward the lights. It was the car, and the driver in the UN uniform, parked back in an alley.

"I thought you were back at the spaceport by now," Wales said sourly.

The driver swore. "I wasn't going to run away. But no use tackling that crowd. Didn't I warn you? An Evacuation uniform sets them crazy."

Wales got in beside him. "Let's get out of here."

As they rolled, he asked, "When I left Earth four years ago, there didn't seem a soul who doubted Doomsday. Why are these people doubtful now?"

The driver told him, "They say Kendrick's World is just a scare, that it's not going to hit Earth after all."

"Who told them that?"

"Nobody knows who started the talk. Not many believed it at first. But then people began to say, 'Kendrick was the one who predicted Doomsday—if he really believed it, he'd leave Earth!'"

"What did Kendrick say to that?"

"He didn't say anything. He just went into hiding, they say. Leastwise, the officials admitted he hadn't gone to Mars. No wonder a lot of folks began to say, 'He knows his prediction was wrong, that's why he's not leaving Earth!'"

Wales asked, after a time, "What do you think, yourself?"

The driver said, "I'm going out on Evacuation, for sure. So maybe Kendrick and the rest are wrong? What have I got to lose? And if the big crash does come, I won't be here."

Dawn grayed the sky ahead as the car rolled on through more and more silent towns. It took to a skyway and as they sped above the roofs, the old towers of New York rose misty and spectral against the brightening day.

In the downtown city itself, they were suddenly among people again. They were everywhere on the sidewalks and they were a variegated throng. Workers and their families from the midwest, lumbermen and miners from the north, overweight businessmen, women, children, babies, dogs, birds in cages, a shuffling, slow-moving mass of humanity walking aimlessly up and down the streets, waiting their call-up to the buses and the spaceports and the leaving of their world.

Evacuation Police in their gray uniforms were plentiful, and to Wales' surprise they were armed. Only official cars were in the streets, and Wales noticed the frequent unfriendly looks his own car got from faces here and there in the throngs. He didn't suppose people would be too happy about leaving Earth.

The big new UN Building, towering over the city, had been built thirty years before to replace the old one. He had supposed it would be an empty shell, now that the whole Secretariat was out on Mars. But it wasn't. Here was Evacuation headquarters for a whole part of America, and the building was jammed with officials, files, clerks.

He was expected, it seemed. He went right through to the regional Evacuation Marshal's office.

John Fairlie was a solid, blond man of thirty-five or so, with the kind of radiant strength, health, and intelligence that always made Wales feel even more lanky and shy than he really was.

"We've been discussing your mission here," Fairlie said bluntly. He indicated the three other men in the room. "My friends and fellow-officials—they're assistants to Evacuation Marshals of other regions. Bliss from Pacific Coast, Chaumez from South America, Holst from Europe—"

They were men about Fairlie's age, and Wales thought that they were anxious men.

"We don't resent your coming, and you'll get 100 percent cooperation from all of us," Fairlie was saying. "We just hope to God you can get Evacuation speeded up to schedule again. We're worried."

"Things are that bad?" said Wales.

Bliss said gloomily, "Bad—and getting worse. If it keeps up, there's going to be millions still left on Earth when Doomsday comes."

"What," asked Wales, "do you think ought to be done first?"

"Find Kendrick," said Fairlie promptly.

"You think his disappearance that important?"

"I know it is." Fairlie strode up and down the office, his physical energy too restless to be still. "Listen, Wales. It's the fact that Kendrick, who first predicted the catastrophe, hasn't himself left Earth that's deepening all these doubts. If we could find Kendrick and show people how he's going to Mars, it would discredit all this talk that his prediction was a mistake, and that he knows it."

"You've already tried to find him?"

Fairlie nodded. "I've had the world combed for him. I wish I could guess what happened to him. If we could only find his sister, even, it might lead to him."

Yes, Wales thought. Martha and Lee Kendrick had always been close. And now they had vanished together.

He told Fairlie what had happened to him in the Jersey City. Neither Fairlie nor the others seemed much surprised.

"Yes. Things are bad in some of the evacuated regions. You see, once we get all the listed inhabitants out, we can't go back to those places. We haven't the time to keep going over them. So others—the ones who don't want to go—can move into the empty towns and take over."

"Why don't they want to go?" Wales studied the other's face as he asked the question. "Five years ago, everyone believed in the crash, in the coming of Doomsday. Now people here are skeptical. You say that Kendrick might convince them. But what made them skeptical, in the first place?"

Fairlie said, "I don't know, not for sure. But I can tell you what I think."

"Go ahead."

"I think it's secret propaganda at work. I think Evacuation is being secretly sabotaged by talk that Doomsday is all a hoax."

Wales was utterly shocked. "Good God, man, who would do a thing like that? Who would want millions of people to stay on Earth and die on Doomsday?"

Fairlie looked at him. "It's a horrible thought, isn't it? But fanatics will sometimes do horrible things."

"Fanatics? You mean—"

Fairlie said, "We've been hearing rumors of a secret organization called the Brotherhood of Atonement. A group—we don't know how large, probably small in numbers—who seem to have been crazed by the coming of Doomsday. They believe that Nereus is a just vengeance coming on a sinful Earth, and that Earth's sins must be atoned by the deaths of many."

"They're preaching that doctrine openly?" Wales said, incredulous.

"Not at all. Rumors is all we've heard. But—you wondered who would want millions of people to stay on Earth till Doomsday. That's a possible answer."

It made, to Wales, a nightmare thought. Mad minds, unhinged by the approach of world's end, cunningly spreading doubt of the oncoming catastrophe, so that millions would doubt, and would stay—and would atone.

Bliss said, "The damn fools, to believe such stuff! Well, if they get caught on Earth, it'll be the craziest, most ignorant and backward part of the population that we'll lose."

Fairlie said wearily, "Our job is not to lose anybody, to get them all off no matter who or what they are."

Then he said to Wales, with a faint smile, "Sorry if we seem to be griping too much. I expect your job on Mars hasn't been easy either. Things are pretty tough there, aren't they?"

"They're bound to be tough," said Wales. "All those hundreds of millions, and more still coming in. But we'll make out. We've got to."

"Anyway, that's not my worry," Fairlie said. "My headache is to get these stubborn, ignorant fools who don't want to go, off the Earth."

Wales thought swiftly. He said, after a time, "You're right, Kendrick is the key. I came here to find him and I've got to do it."

Fairlie said, "I hope to God you can. But I'm not optimistic. We looked everywhere. He's not at Westpenn Observatory."

"Lee and Martha and I grew up together in that western Pennsylvania town," Wales said. "Castletown."

"I know, we combed the whole place. Nothing."

"Nevertheless, I'll start there," said Wales.

Fairlie told him, "That's all evacuated territory, you know. Closed out and empty, officially. Which means—dangerous."

Wales looked at him. "In that case, I'll want something else to wear than this uniform. Also I'll want a car—and weapons."

It was late afternoon by the time Wales got the car clear of the metropolitan area, out of the congested evacuation traffic. And it was soft spring dusk by the time he crossed the Delaware at Stroudsburg and climbed westward through the Poconos.

The roads, the towns, were empty. Here and there in villages he saw gutted stores, smashed doors and windows—but no people.

As the darkness came, from behind him still echoed the boom-boom of thunder, ever and again repeated, of the endless ships of the Marslift riding their columns of flame up into the sky.

By the last afterglow, well beyond Stroudsburg, he looked back and thought he saw another car top a ridge and sink, swiftly down into the shadow behind him.

Wales felt a queer thrill. Was he being followed? If so, by whom? By casual looters, or by some who meant to thwart his mission? By the society of the Atonement?

He drove on, looking back frequently, and once again he thought he glimpsed a black moving bulk, without lights, far back on the highway.

He saw only one man that night, on a bridge at Berwick. The man leaned on the rail, and there was a bottle in his hand, and he was very drunk.

He turned a wild white face to Wales' headlights, and shook the bottle, and shouted hoarsely. Only the words, "—Kendrick's World—" were distinguishable.

Sick at heart, Wales went by him and drove on.