Chapter Three

When I was about twelve years old, Dad and I were rock climbing, when he asked me an unexpected question. Maybe I could even call it an unwelcome question, because rock climbing was always my special time with Dad and I just wanted to enjoy being outdoors with him.

“Jocie? What does it mean to you to be a Christian?” he asked.

I’d never really thought about it before. I had always been a Christian. It was just who I was.

“It means that Jesus died for my sins,” I said.

I stretched for a hand hold that was nearly out of my reach, and ended up hanging by one hand for a moment, until I found places for my feet. There were much easier holds available, but I knew that such a simple answer to Dad’s question wouldn’t end the discussion; so I might as well try to delay him by climbing hard, and give myself more time to think.

“That’s what it means for all of us,” he said. “What does it mean to YOU?”

This time I didn’t reply right away. I knew he wouldn’t mind waiting, so long as I was thinking about the answer.

“It’s both happy and sad,” I said. “The happy part is obvious. I have a Savoir who loves me.”

I paused, as I switched my hand holds.

“What’s the sad part?”

“That’s pretty obvious too. I feel hated. There are men and women out there with black lines on their faces, who would gladly snatch me and sell me just because of my genes.”

“Is being a Christian genetic now?” he asked.

“You know what I mean, Dad.”

We each hauled ourselves over the last bit and sat on the very top of the rock formation.

“That was a great climb,” Dad said. “You really stretched your abilities, but are you sure you took the right route to get here?”

“There is no right way to get here. You choose a path and it takes you to the top.”

Dad smiled, and it became clear that there was a lesson in his questions.

“I’m so glad to hear you say that,” he said. “I’ll tell you why while we eat, but first, let’s pray.” It was something Dad and I did at the top of every climb. We’d sit on the rock, look out over creation, and say thanks. For Dad, giving thanks always began with the same three words, spoken directly to Jesus: “My dear friend.”

Dad handed me an apple.

“Today is the anniversary of the death of a man who chose a very difficult path on earth,” he said. “Even now, most people refer to him as ‘Michael the Assassin’, but that’s not how I remember him. I remember the gentle man who loved his neighbor as he did himself - so much so that he sacrificed himself to save the life of another. The woman he saved was named ‘Zip’ and she then nearly sacrificed herself while saving a whole town. They had very different routes to faith, neither of which is better or worse than mine or yours. I’m just happy that we’ve all arrived at the same place.”

A large drop of rain hits the top of my head; then another hits my shoulder. Sudden afternoon rains are a common occurrence for Colorado summers, but are not good news for rock climbers. We’ll have to descend quickly.

By the time we’ve reached the bottom and are packing our gear, we’re in a steady shower.

“I hate rain,” I say.

“Really?” Dad asked. “I’ve always enjoyed it.”

He raised his chin so the rain could pour directly onto his face, until the drops were running from his jaw and down his neck. After a while, he looked at me with a big smile on his face that did nothing to hide the sadness I knew was just under the surface.

******

Austin and I share a bewildered look after Zera’s announcement.

“In a way, your dad named me. My full name is ‘Zerahiah,’ which means ‘brightness of the Lord.’ My mom thought it was the perfect name, as she watched the map of the earth light up behind your dad.”

“Who’s your mom?” Austin asks.

“Zipporah, though most everyone calls her ‘Zip’.”

Zera gets a sad and confused look on her face.

“They really never mentioned me? Not once?”

“Sorry,” I say.

“Your dad has always had a strange relationship with our family. Mom always said that he keeps too many secrets for his own good. I just never thought that I was one of them.”

Her face returns to smiling and happy, as if she’s completely shrugged off her earlier disappointment and moved on.

“If you know Mom and Dad so well, where are they?” I ask.

“Let’s talk more downstairs,” she says.

“This house doesn’t have a basement,” Austin replies.

Zera studies our faces to see if we’re serious.

“Mom’s right,” she says. “Your dad sheltered you too much.”

She leads us to the front room and walks straight to the fireplace. When the house was built, it was probably a real fireplace, because the house has a brick chimney. It now has an electric fireplace that’s been inserted into the opening. She slides her hand along the side of the insert and presumably pulls on a hidden release, because she’s able to swing the entire insert out of place, revealing a hole with a ladder leading down.

“Welcome to Mount Sinai House,” she says, when we all reach the bottom.

“It can’t be,” I say. “Four was disbanded ages ago. It was part of the agreement to restore the First Amendment to its original wording and guarantee religious freedom.”

“Four may have been disbanded, but some of the houses are still out there. Mom gave me the location of this one, but it took me a long time to find the buried escape tunnel.”

“That’s how you got into the house without opening any doors or windows,” Austin says.

“Are you just now figuring that out?” she replies.

People have fussed over Austin his entire life. Neither of us is used to the way Zera speaks to him.

“Well, do you know where our parents are?” I ask.

Zera takes off her hat, releasing her long, dark hair with a shake. I see Austin’s pupils expand slightly.

He finds her attractive.

Next off is her black leather jacket. Her shirt is sleeveless, and on her upper right arm is a tattoo of a cross with black lines snaking away from it, much like the lines that begin at the point where Corps members were injected.

“No, I don’t. I also can’t tell you where to find any of your aunts and uncles or any former member of Four. I can’t even find my own mother.”

“Then what do you know?” Austin asks.

“I know that something big is happening and the planning has been in the works for a long time. Mom has always kept herself in shape, but a year ago she started a physical training program so hard it was like she was getting ready to fight a war all by herself.”

“Did you notice Aunt Cindi when we were there last month?” Austin asks me. “She looked like she had gained a lot of muscle. I thought she was just fighting the fact that she’s pushing forty-years- old, but …”

“… and Dad never stopped training,” I say. “Whatever is happening, he’s known for decades.” I think about the sadness in Dad’s eyes.

He’s borne so many burdens … why has another been thrown onto his back?

“What else can you tell us?” I ask.

“Two things: I overheard Mom mention ‘Five-X.’ Given that Mom and all the old members of Four took their game up a notch, I figure that’s what they’re calling themselves now. The other is this …”

She reaches into her pants pocket and brings out a piece of paper.

“Mom left this for me the day she disappeared. The front has the coordinates of this house … but there’s a drawing on the back that might mean something,” Zera says.

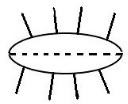

Austin holds out his hand, naturally assuming he should see the paper first, but Zera hands it to me. I look at the drawing:

Austin looks over my shoulder.

“Did Mom and Dad leave on a spaceship?” he asks.

“I thought it was the sun,” Zera adds.

“It’s from Dad.” I say. “It’s a puzzle.”

“What does it mean?” Zera asks.

Austin and I exchange a look.

“No clue,” I say.

******

For the next hour, we debate different theories about what the strange shape could mean, but get no closer to understanding what Dad is trying to tell us.

“My mom always said your Dad has a messed up mind, but that God made him that way for a reason,” Zera says. “Didn’t you two get any of it from him?”

“Austin is the gifted one,” I say.

“So I’ve heard,” Zera replies. “He’s a real ‘boy wonder’ all right.”

“When it comes to puzzles, Jocie is the Paulson you’re looking for,” Austin replies. “Dad was always giving her puzzles to solve when we were little. She even solved ‘The Impossible Puzzle’ all by herself when she was thirteen.”

“Dad did it when he was eight,” I say.

I remember how disappointed he looked when it took me so much longer than him.

“Are either of you hungry?” Austin asks. “I’m going upstairs to make some sandwiches.”

“There are some blackberries growing near the creek, just outside the end of the escape tunnel. I’ll go pick some,” Zera says.

“Blackberries?” I say. “Dad loves blackberries. Sometimes when he eats them, he looks like he’s having a spiritual experience. It takes a while though, because he crushes them against the roof of his mouth, one at a time.”

“I suppose he was bound to either love them, or hate them,” Zera replies.

“What do you mean?” I ask.

“Blackberries were part of Henry’s torture. The crown was made of blackberry canes.”

“Oh,” I say. “We’ve never seen the video of what happened inside the mountain. Mom wouldn’t allow it in our house. She said seeing it live was enough for her.”

“My mom always says that closing your eyes won’t make evil go away,” Zera replies.

My mind shifts into a different gear.

It can’t be a coincidence.

“She has that look,” Austin says. “Expect a solved puzzle … right … about … now.”

“The dashed line,” I say. “When I was little, Dad would create three-dimensional paper puzzles for me to solve. You always cut or folded along a dashed line. Look at what happens if you cut Dad’s drawing along the dashed line.”

I carefully rip the piece of paper.

“One is a sunrise and the other is a sunset?” Austin says.

I flip one of them over:

“Closed eyes,” I say.

“So?” Austin asks.

“Dad would send a puzzle that’s also a personal message; something that only we would know about him, so only we would know what it means. Haven’t you ever watched Dad when there’s a pretty sunset? He scans the colors from north to south as far as Pike’s Peak, but he closes his eyes before they reach Cheyenne Mountain - as if closing his eyes will make what happened there go away. We live in the shadow of the mountain where he was tortured, but he won’t look at. It’s also the last place anyone would expect him to hide.”

******

“Your mother invented the hacked com. Why are we running to the mountain instead of taking a bus?” Zera asks.

“It’s what our family does,” I reply. “It’s good exercise, and there’s no way we can accidentally show up on the grid this way.”

“Besides, no public buses go there,” Austin adds.

“This is easy,” I say. “Dad taught me to rock climb in North Cheyenne Canyon. Try doing the run with climbing gear on your back.”

“Rock climbing?” Zera asks.

“Yeah. It’s great for building finger and arm strength. And when you get to the top, first you get to enjoy the view and then you get to rappel down.”

“And it was her special thing to do with Dad,” Austin says.

“You got to cycle with him,” I reply. “That was just as many hours.”

“Aren’t you a little old for playing on hover bikes?” Zera asks Austin.

“We didn’t use hover bikes. We used old-style bikes with wheels.”

“Did you rob a museum?” Zera asks.

“No, we made them ourselves. We even created our own lightweight composite material for both the frame and the wheels. We had to learn a lot of chemistry, but when we were done, the bikes were both lighter and stronger than most titanium or aluminum composites.”

We reach the end of the old dirt path, which is an overlook giving us a view out onto the plains. It also allows us to see the old road that leads to the underground base where Dad was tortured, but not the entrance itself.

“Zera?” I say. “What happened to Dad in there?”

“You don’t know?”

“I know he was beaten and whipped, and that he almost died. I know that he asked the world if they wanted God in their lives and they lit up a map to say ‘yes’ … but …”

“Nobody could go through that sort of torture and come through it unaffected, Jocie. My Dad once said it took my Mom years to recover from her role in the whole thing. She still stockpiles water.”

I tilt my head when Austin nods his head a miniscule amount in understanding, while I don’t understand the reference. He knows that he’s been “caught,” but doesn’t explain. He doesn’t want my brain to treat his reaction as a puzzle, so he changes the subject.

“Can you see the road well enough through binoculars to tell if there’s been traffic?” he asks.

I take binoculars out of my pack and scan the road. The integrated electronics allow me to zoom to the point where the road appears to be about one hundred meters away, rather than several kilometers.

“There’s no dust on the hover plates; so someone has been there.”

“Your parents would have come on foot, like us,” Zera says. “What about footprints?”

I hand the binoculars to Austin and look Zera in the eye.

“Mom and Dad don’t leave footprints.”

When we reach the tree line along the hover plates, we have a view to the giant tunnel entrance. There are no signs that anyone is around; so we sprint the two hundred meters, then stop to rest once we’re inside. There are dim lights above us, many of which are flickering.

“How do you plan to get through the blast doors?” Zera asks.

“I don’t. If Mom and Dad are here, they’ve already taken care of that for us.”

“I bet they had Albert do it with explosives,” Austin says.

I give him a practiced ‘big sister’ look.

“If you tried it, you’d create a multi-ton obstruction. Big doors like that are perfectly balanced and aligned. If you throw it off with explosives, it might never open again. The control systems here are old; so the easier route would be to hack into them.”

We reach the massive door, we find it closed.

“Now what?” Zera asks.

I find a flashlight in my pack and shine it along the walls. Ten meters from the door, I find a spot where a conduit has been cut and an ancient computer pad patched into the system.

“This is Mom’s handiwork,” Austin says, as he taps at the pad. “It looks like she used an old transmitter wire to gain access. It’s protected with both voice recognition and a password.”

“Voice print recognized. Hello, Austin,” the pad says - in Mom’s voice - followed by “Password, please.”

Austin looks at me and I shrug.

“How should I know?” he says.

“Incorrect password, error code E Four-Ten, access denied,” the pad responds.

Austin turns to me.

“It could be anything,” he says.

“She just gave you the password,” I say. “E Four-Ten isn’t an error code. It’s a Bible verse.”

Austin gives me a blank stare as I approach the pad.

“Computer,” I say.

“Voice print recognized. Hello, Jocie. Password, please.”

“If either of them falls down, one can help the other up. But pity anyone who falls and has no one to help them up,” I say.

We hear a series of clunking sounds inside the door. Austin and Zera don’t move, as I pass between them and to the door. There’s a handle, which I pull on, and the giant door begins to swing outward. I was correct that the door is very well balanced, but Austin lends a hand and we swing it open just enough to pass through. I search the inside for another computer pad, but don’t find one.

“We’d better leave it open,” I say.

“I still don’t know how we got it open in the first place,” Austin says. “What was that password all about?”

“It’s Ecclesiastes 4:10. It’s so ingrained into the way Mom and Dad approach life together, they should have used it as a wedding vow. I think it was also a message to us … to watch each other’s backs.”

“Why is there no pad on the inside to let us back out?” Zera asks.

“Because they didn’t stay here, and neither should we,” I reply. “There must be something in here that we’re supposed to find. You’ve watched the footage of Dad’s time here, Zera. Any idea where we should go?”

“He only spent time in two rooms: the one where they held him, and the stage.

I expect the complex to be a maze of corridors, but it looks more like they hollowed out a giant cave and then built a small town inside of it, complete with roads and street lights. Despite the size of the complex and the number of buildings, Zera takes us straight to the room where Dad was held. There’s a large screen on the wall, and an old-fashioned clock with arms, which is on the floor and smashed to pieces.

Time’s up?

There’s nothing else that might be a clue to finding Mom and Dad; so we move on.

We find the stage even faster, thanks to signs reading “Auditorium.” A single spotlight is shining on two wooden posts that are bolted to the stage. I can see the lighting controls and conclude that Mom rigged that light to come on when either Austin or I said the password.

I remember this place. I was here when I was four years old.

Austin and Zera stay back, as if they’re afraid to walk on hallowed ground, but I jump onto the stage and approach the posts, just as I did when I was little; so they follow me.

I turn around, and see that Austin looks as white as a sheet.

“That black stuff on the floor …” he says. “…it’s Dad’s blood. Why would someone write that in Dad’s blood?”

I look down at the black stains on the floor. Someone has recently scratched the words: “God’s Judgement.”