Chapter 18: Olde Towne

The ground level of the Kid’s Motorway station was just a waiting room for parents, with hard benches and a vending machine. Up the narrow stair that said Employees Only, Teina found a comfortable little office and lounge.

Jimox brought up their sleeping bags. Side by side, they knelt on a couch and pressed their faces to the window.

The fantastic World Tree, with its slides and ropes and everything else a child could want, stood in silhouette against the evening sky. From this height, the pair could see all the winding streets of Olde Towne, now deep in shadow.

“Sometimes I’ve been sad,” Teina began, “when I realized the plague stole half my childhood. Now I’m in the one place in the world that every kid dreamed of going, and it’s free, we can stay as long as we want, and none of it’s burned!”

“Makes sense,” Jimox said. “No one lived here. I bet they locked the place up tight when the news said the plague was out of control.”

“That was three days before Burning Day.”

Jimox nodded, and continued gazing at their new home as the light faded from the sky.

They took the next morning to clean out the little refrigerator in the employee lounge, and salvage what they could from the vending machine downstairs.

NEBADOR Book Eight: Witness 90

With pistols and extra ammunition on their belts, sun hats on their heads, day packs, and a map of the theme park in hand, they began to explore.

Although only four streets wound through Olde Towne, from the ground it seemed like an endless maze, and the many balconies, foot bridges, and dead-end alleys added to the feeling of being lost in a tangled city of times past. Every possible shop, restaurant, and theater lined the streets, but all were dark and locked.

Teina kept track of their location on the map, and Jimox watched for dogs.

Only one showed its face, and dashed away after taking a good look at the tall, confident monkey mammals.

A little lunch counter once boasted varnished wood and polished brass, but now the wood was dusty and the brass tarnished. The refrigerator and freezer doors bulged open with fungus and slimy mold, and the pastry case contained something green that the pair of theme-park visitors, faces pressed to the window, couldn’t name.

A theater once showed old cartoons constantly. The snack counter appeared ready to pop popcorn by the bucket, but now stood silent, waiting for Similand to open again in the morning, a morning that never came.

The furry dolls in a gift shop, based on every possible fairy-tale character, looked back at Jimox and Teina with unblinking plastic eyes.

“When I was six,” Teina remembered, cupping her hands around her face to better see through the dusty glass, “I would have loved to have every doll in this store. Now . . . they just make me sad.”

Jimox said nothing, but touched her shoulder gently with his tail.

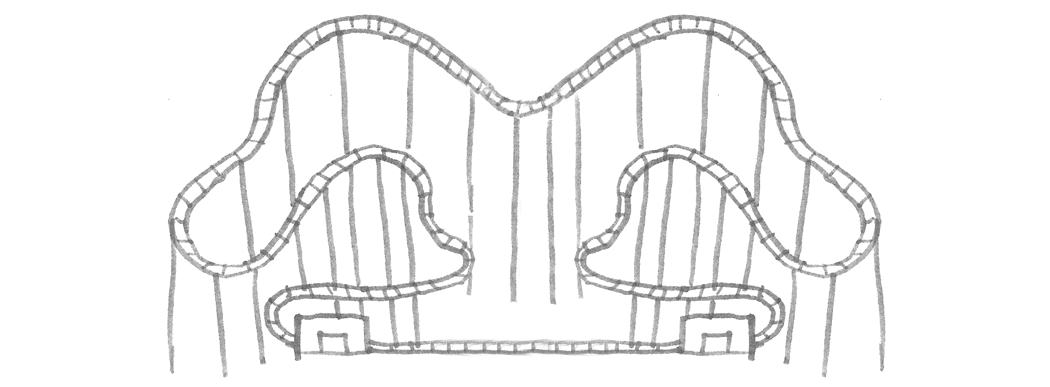

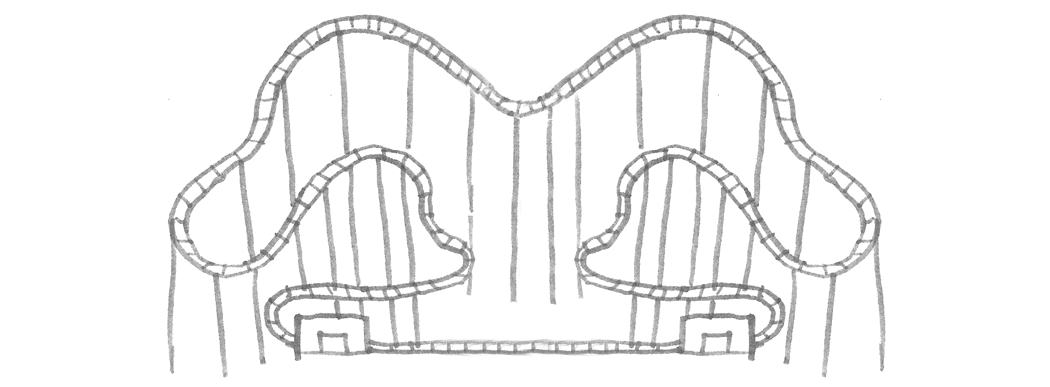

Eventually they emerged from the maze of streets and stood before the great World Tree. It towered, according to the map, more than two hundred feet above them. On this side, the entrance to the ladders, ropes, and slides beckoned to the only two visitors in the park.

NEBADOR Book Eight: Witness 91

The child in each of them was ready to dash right in and play. Another part — the part that had kept them alive for the last seven years — was willing to wait, look, and listen.

“I think . . . today we should just do a walk-through on the ground,” Jimox proposed.

“Agreed. We need to know what’s lurking in this place.”

Almost before Teina finished speaking, something in the huge tree jumped several feet, a bird’s cry of pain was quickly cut off, and feathers came floating down.

“Cat!” she declared, shielding her eyes and looking up.

“Yeah. Dogs couldn’t get up the ladders.”

Nothing more of the contest could be seen, but judging from the silence, the cat had won. The pair of monkey mammals turned and looked at the entrance to the western part of Similand.

NEBADOR Book Eight: Witness 92