Chapter 12: Cattle Town

“Can you believe it? There are actually rewards out for the capture of the so-called sorcerers and witches who SET the fire at Lumber Town!” Toli gasped out, red-faced.

Ilika couldn’t keep from laughing.

“It gets worse,” Sata jumped in. “You won’t be laughing when you hear this.”

Ilika tried to compose himself.

“One of the things they’re looking for is a young crippled witch who rides a donkey.”

Mati frowned deeply, then cracked a little smile.

Ilika grinned at her. “I’m surprised we got this far without trouble.”

“I don’t think the witch-on-a-donkey is common knowledge,” Toli explained. “We only know because I read the stuff on the wall at the guard station while Sata was asking about inns.”

The pair of scouts continued their report, describing the shops and other businesses, the ever-present smell of cattle, and the dust billowing from countless animal pens. Then Sata dropped the second bomb shell. “It’s got a slave market.”

Dead silence. None of the ex-slaves had set eyes on one since Ilika led them away toward the bath house. They had seen slaves at Port Town, and a few at Lumber Town, but had held in their anger and dread. Now the very worst part, the auction block itself, awaited them in the town that was their

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 84

destination. Based on Toli’s description of it’s location, it would be impossible to avoid.

“And there’s another problem,” Sata continued.

“Another one?” Boro burst out with wide eyes. “Did you find the gates of the Underworld itself next to the bakery?”

Sata grinned. “Almost. I think there’s a . . . what do you call it when lots of people are sick?”

“Epidemic,” Ilika answered. “What do you know about it?”

“I know everything, because I asked questions. It’s food poisoning, and it happens every year, late summer and fall, when the weather is hot. We saw children puking right in the streets, and no one cared because most of the adults were doing it too. There’s a sour stench all over town.”

“I bet it’s the meat,” Ilika speculated. “Without refrigeration . . .”

“Re . . . what?” Buna asked, squinting.

“You can figure that out!” Toli burst out at her. “Just take apart the word.

Re-frig-erat-ion. Place of making cold again.”

Ilika nodded, but wore a slight frown.

Buna scowled at Toli.

“Do you have re . . . frigerat . . . ion in your country?” Kibi asked, ignoring Toli and Buna.

“Yes. But there are ways of keeping food good without it . . . and they obviously aren’t using them here. Fresh meat is about the hardest thing to handle.”

“This town is all about meat,” Toli declared. “I think they’d rather die than quit eating meat.”

“Sounds like they are. Anything else to consider?”

Sata added some details about the shops, then fell silent.

Ilika took a slow breath. “Good scouting job, you two. We need to do some thinking.”

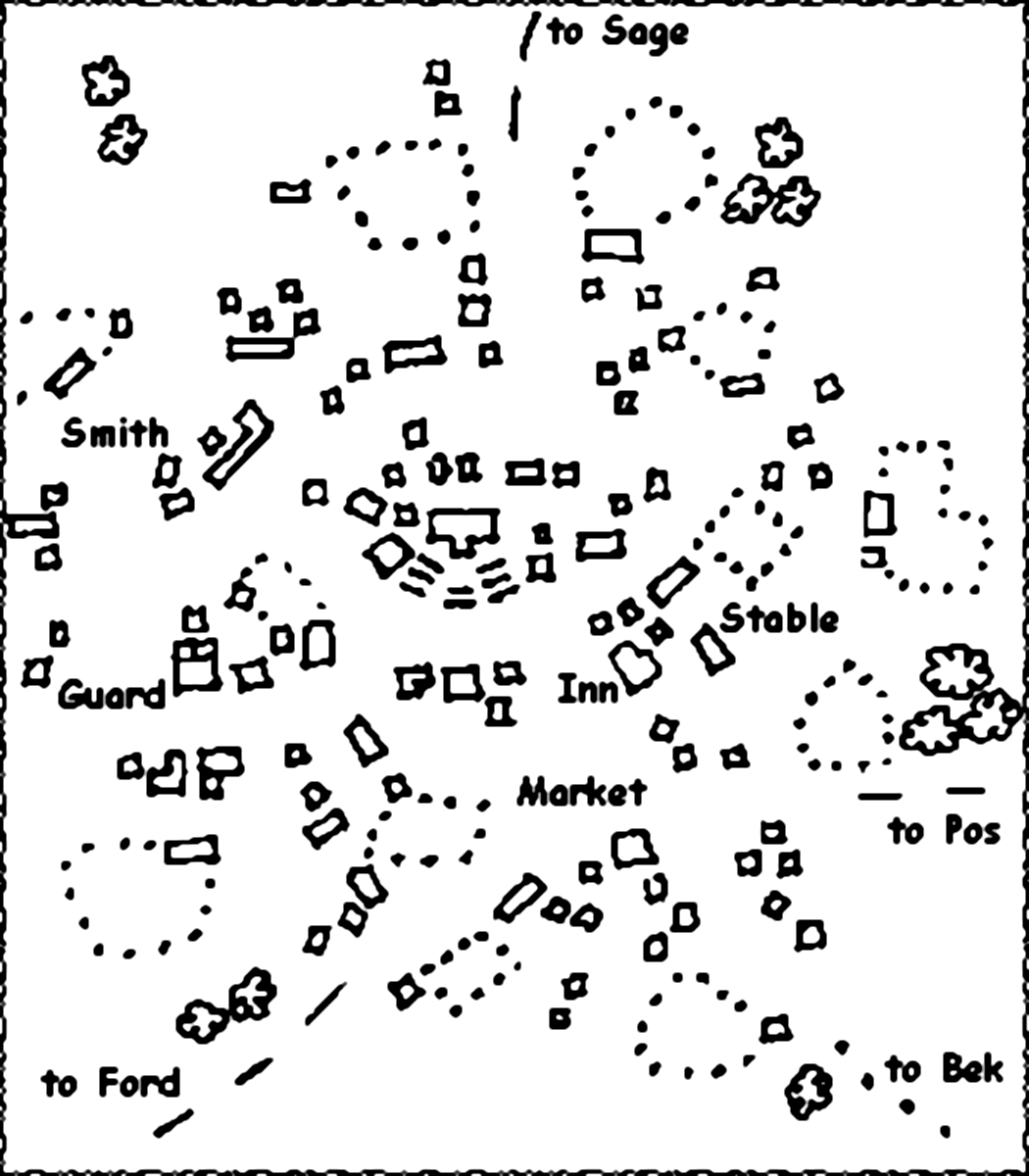

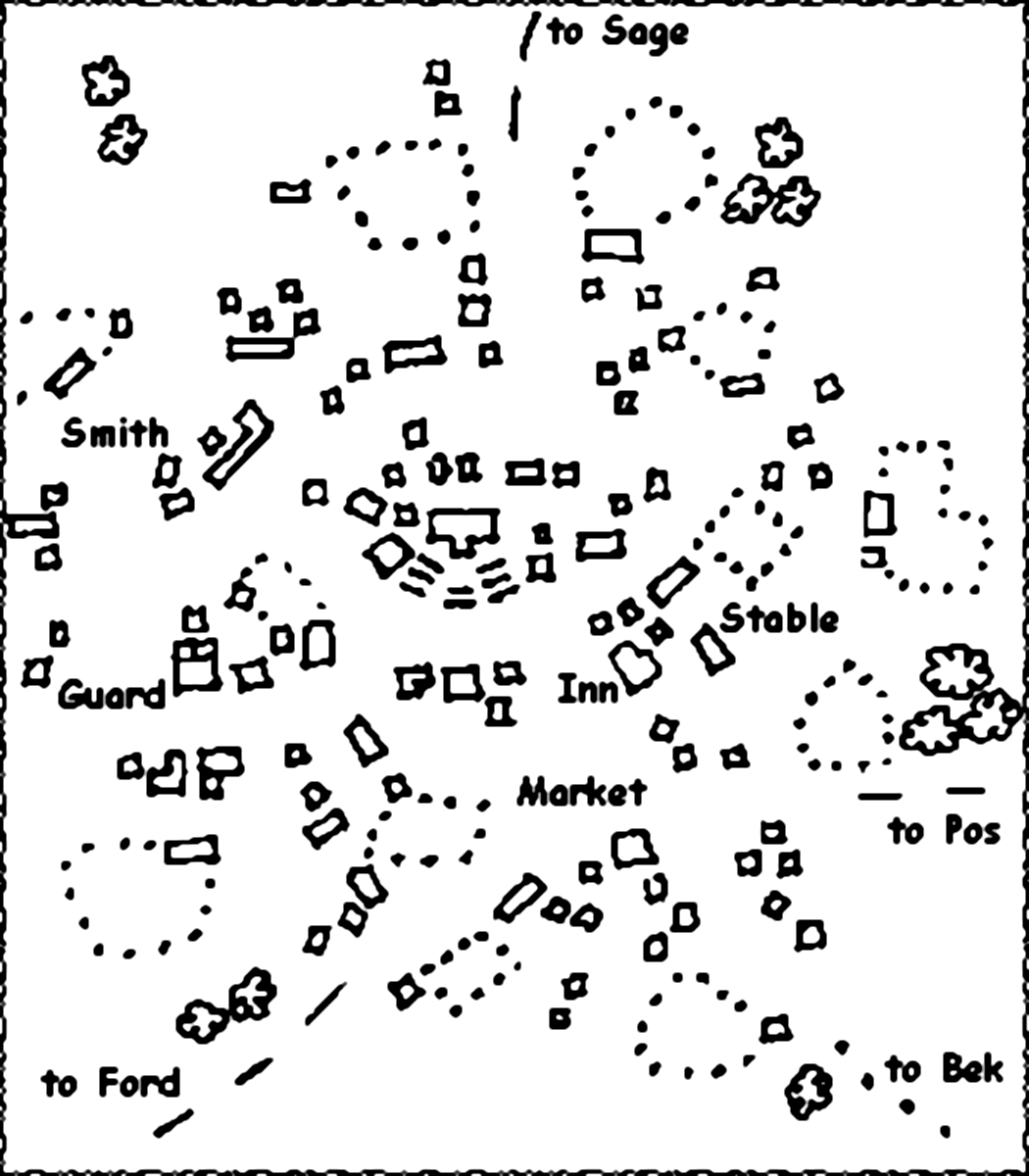

“Yeah!” Kibi blurted out. She already had Ilika’s shoulder bag open and the map unfolded in her lap. “I want to have my birthday party . . . right here!” she said, pointing to somewhere on the map.

Everyone gathered around to look. She pointed to a little village several miles to the east on the road to the desert.

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 85

“Hmm,” Toli considered. “I want to have mine . . . here!” He pointed to another village deep in the grasslands southeast of Cattle Town.

The ten travelers used the rest of the afternoon to work their way eastward. For hours they trudged across sagebrush-covered prairie and scrambled in and out of dry washes. Eventually they found what they were looking for — a well-hidden gully with a spring-fed stream, and no signs of use by people or cattle. A pair of rabbits, nibbling the grass by the stream, bounded away and disappeared into a hole.

Rini scouted southward, and found the road that ran east from Cattle Town only a short walk down the gully. But, he explained with a smile, the stream soaked into the ground before getting that far, so no one would be tempted to explore it.

Once beds were unrolled in the shade of the small, thorny trees, they all quickly agreed on two things — Mati and Tera weren’t going anywhere near Cattle Town, and Ilika should stay near Mati at all times, as he was the only one who could fend off soldiers.

Ilika took questions all evening about the ways food could spoil or transmit diseases, and what could be done about it. They had all been sick from bad food many times. Their masters had usually blamed it on the slaves themselves. Some of them had heard that evil spirits were involved.

Sata was not exempt from the experience of food poisoning. She remembered clearly her mother telling her that if food went bad, there was no way to make it good again — it had to go. She understood why after Ilika taught them about the toxins that remained in spoiled food even after sterilizing it with heat.

Ilika limited his description of food preservation methods to those available in this culture. He asked them to forget about refrigeration, as it wasn’t going to happen here any time soon. Around the campfire that evening, as the air cooled and the land around them became still and silent, he made a list of things they should not eat or drink in the town, including, to their surprise, water.

Even though Kibi chose not to celebrate her seventeenth birthday party at

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 86

Cattle Town, she wanted a bath in the cleanest, warmest water available. As the sun rose in a clear sky, she, Neti, and Boro walked the dusty streets for an hour to learn where everything was. They often had to make way for groups of cattle driven from place to place.

When they walked by the slave market, Neti just stood in the street and cried. The other two led her away, and apple tarts from the bakery brought smiles back to their glum faces.

While waiting for bathing tubs to fill, Kibi bought new wool pants. Neti looked at socks, but had trouble deciding. Boro went off to find a new tunic.

With clean bodies and hair, wearing fresh clothes, the two girls joined Boro at the marketplace, and they soon had a rucksack filled with meatless baked goods, fully-cured cheeses, and sheets of paper for Ilika. As mid-day approached, the three friends headed east along the little-used road toward the desert to share the bounty with their fellow travelers.

That afternoon, Toli, Buna, and Misa stood in the street feeling quite sick.

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 87

They hadn’t been eating meat, soft cheese, or any other dangerous foods.

In full sight of everyone on the street, poor women, orphaned children, old men, and the simple-minded of every age were bought and sold, jeered at, and sometimes whipped.

Toli and Buna didn’t remember it being so bad when they were the ones on the block. Their survival during those years had required them to numb themselves, not feel, and not think. Now they were free to do both.

The three took baths, replaced worn out items of clothing, sampled the baked goods, and stocked up on dried fruits and vegetables for the group. But in between tasks, and before returning to camp, they kept coming back to the slave market and standing there for as long as they could tolerate, wondering if something could be done.

That evening around the fire, Kibi had an idea that was much easier to talk about than the slave market. She suggested they attempt to teach the butchers in the marketplace, and the cooks at the inns, some of the things they knew about keeping food from spoiling.

Most everyone was excited about the idea. They had never before applied what they were learning. This situation, this town, seemed to cry out for the knowledge they possessed.

To their surprise, Ilika didn’t share their excitement. “There are many things, besides lack of knowledge, that keep people from living as well as they might. Traditions and customs run deep, and can be very hard to change.”

“But don’t you think they’d be willing to learn,” Toli asked in a defensive tone, “if it would keep their friends and families from being sick all the time?”

“That might motivate some of them. You are welcome to try. I hope you will keep it quiet, one on one, out of sight of the guards. And you can’t start until tomorrow afternoon, so Sata and Rini can do some shopping.”

The group spent the rest of the evening talking about the methods the people of this cattle-raising area could use to keep their meat and other foods safe. They agreed that if they could teach the people the temperature, moisture, and acidity ranges where bacteria thrived, the preservation methods would be obvious — heating, drying, salting, and pickling.

But as they finally let the fire die down and readied their bedrolls, most of

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 88

them kept thinking about the slave market.

Because of Rini’s small size, Boro got an extra trip into town. He didn’t mind — he planned a warm bath and some shopping for birthday gifts.

Rini observed the flies crawling on the meat at the butcher stands, and saw gallons of spoiled milk poured into the gutters. He smelled an abandoned bowl of stew, almost as bad as the milk. He saw a little boy lose his breakfast, then run off to look for something else to eat.

All these things made Rini feel deeply, but he remained silent as his friends made plans to teach the people of Cattle Town all the things they knew about food preservation.

Deep Learning Notes

This plan of Cattle Town might be found on the guardhouse wall.

The fire at Lumber Town in Book Two proved useful to Ilika’s enemies.

People feel much more in control of a disaster when they can blame it one someone. Nature cannot be arrested, and God cannot be punished, but a person can be. It probably took very little work, on the part of the priests, to start the rumor the Ilika and his students were sorcerers who set the fire. The pre-existing rumor of sorcerers traveling north from Port Town helped, of course. The soldiers believed the accusation, or just played along, because law enforcement agencies have a better image, and appear to be doing their jobs, if they have a suspect. The guilt of the suspect is of secondary importance, and sometimes of no importance at all (a “scapegoat”). The desire for revenge is a strong human need after a loss, and if people can’t take their anger out on the “suspect,” they might turn on the soldiers, the priests, or each other.

When considering the food poisoning epidemic, remember that people in a medieval culture know nothing of “germs.” Combine that with the strong human tendency to need to “see it to believe it.” The result is an attitude of

“that’s just the way it is,” or status quo, and so few people would try to do

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 89

anything about the problem.

All of the parts of re-frig-erat-ion are Latin or Greek words. In order, they are: again-cold-make-place. When we say the word with English pronunciation rules, some of the breaks between the original words get slurred into something like: re-fri-gera-tion.

Why did the group want to find a spring-fed stream with no signs of cattle?

Even though people try very hard not to believe something unless they can see it, it is impossible to live without being almost constantly affected by unseen forces and life forms. The idea of “spirits” was invented long ago, “good spirits” if they helped us (like sunshine on our crops), “mischief spirits” if they made life interesting without great harm (like the “fairies” who hide the tools we put in the wrong place), and “evil spirits” who cause pain and suffering (like bacteria and viruses). This is not to suggest that there are not also real spiritual beings, as the author is a theist, but only to point out that we often confuse natural forces and unseen life forms with imagined beings of good or ill-will.

Toxins are poisonous bio-chemicals that are created in good food when it spoils from the action of microbes. Heating, or otherwise sterilizing, the food after it has spoiled will kill the microbes, but the toxins usually remain.

Although water, by itself, cannot “spoil,” it can contain microbes and toxins from another source, such as a dead animal in a stream or well, or animal waste washing into the water. Therefore, Ilika asked them not to drink water while at Cattle Town.

The reason for choosing meatless pastries at the marketplace is obvious. Why did Ilika limit them to fully-cured cheeses?

Of course, no human society has ever developed without knowledge of heat-sterilizing, drying, salting, and pickling (except perhaps in the tropics

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 90

where food is available year-round). Whatever food-handling methods were in use in Cattle Town, they seemed to be adequate for most of the year. Only in late summer, with the arrival of the highest temperatures, did the food-poisoning epidemic arise. The people knew, from years of experience, that most people survived it every year, so they were not motivated to use the extra-ordinary methods that would have been necessary. For example, if fresh meat could be moved from slaughter barn to marketplace successfully most of the year, why take the trouble to cure it for such a short time?

NEBADOR Book Three: Selection 91