CHAPTER 12

DEMITRIEV WAS PERSUADED THAT Anna Basurko was linked to Simmonds’ visit to San Sebastian. According to the Honorary Consul, Jacques Gautier, she was a close friend of a successful writer, Pat O’Connelly, who lived in Paris and owned a large property near Biarritz. Both were friends of the billionaire Pat Kennedy who in turn was linked to Sergei Tarasov, a rich Russian who too had made his money in banking.

Checking the guest list at the Hotel de Londres in San Sebastian for the date that corresponded with Simmonds’ visit to the city he found Kennedy’s name.

What the hell were people like that doing with an insignificant small-time lawyer from Belize? he asked himself, deducting there was definitely something going on, but what?

Checking and crosschecking news reports linked to Kennedy he found nothing remotely related to Simmonds or Wallace. Then looking through Belize news archives he discovered Kennedy's yacht had dropped anchor in Belize City the previous year and Kennedy had been present at the country’s Independence Day celebrations in the company of Anna Basurko and a French archaeologist, René Viel.

There was even a photo of Simmonds looking on whilst Kennedy shook hands with Audrey Joy Grant, the governor of the Belize Central Bank.

Local newspaper archives showed that Kennedy was returning from an expedition in the Alta Guajira in Colombia where he had discovered amongst other things a jade head of Kinich Ahau, the Sun God, a Mayan divinity, similar to that found in a tomb at Altun Ha in Belize.

Perhaps Simmonds had discovered a Mayan treasure?

As Demitriev racked his head he received a message from the Gautier informing him he had learned Basurko and her friend would be attending a conference at the Getty Museum in Santa Monica the following week.

He decided it was time to make acquaintance with Anna Basurko, at least from a distance.

*

Anna had persuaded Pat ‘Dee’ O’Connelly to join her for a symposium at the Getty Center in Santa Monica entitled ‘Tenochtitlan and the daily life of the Aztecs’ where Luis Gutierrez was to make a presentation followed by a round table discussion on medicinal and aromatic plants in Mexico, and after which she planned to follow up with a visit to Luis’ botanical garden in Palm Springs.

In reality Dee didn’t need much persuading, he had been promising his New York publisher, Bernsteins, he would do a couple of TV interviews and in addition attend a couple of book signing events in San Francisco. It was also a belated opportunity to catch up with the usual obligations related to his home on Telegraph Hill where they would be staying during their visit.

A couple of weeks later, once Dee fulfilled his business engagements and settled the details concerning his home in San Francisco, they hit the road in the direction of Big Sur. They had booked a couple of nights at Shutters in Santa Monica, a short ride away from the Getty Center Campus where the conference was being held, before continuing their trip to the botanical gardens and reserve in Palm Springs.

*

‘Of all the countries on Earth,’ Luis commenced, ‘Mexico is endowed with an extraordinary biodiversity. It is the home to a great number of plant species including those essential for much of the world’s food today, maize, beans, peppers and tomatoes, and many rare plants known only to a few privileged botanists of which I am lucky enough to be one.’

Luis went on to talk about the kind of flowers popular amongst gardeners and collectors including cacti, dahlias, salvias and poinsettias. But they were just a very small part of the 18,000 plant species in the country, half of which were endemic, more than the United States and Canada combined and more than twice as much as all of Europe.

He told his listeners between 3,000 to 5,000 of those plants had been used for medicinal purposes since pre-Columbian times by the many different peoples and cultures that occupied that vast territory which ran from the northern deserts of Texas and Nevada to the tropical forests of Guatemala.

Some 3,000 species had medicinal uses in Mexican traditional medicine compared to over 1,500 by the Mayas, 800 by the Nahuas, and 3,000 by the Zapotecs.

Before the arrival of Spanish, Luis told his listeners, the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan had a considerable knowledge of the flora of their and nearby regions which was used to cure many illnesses and during ceremonies to invoke the Aztec gods. Botanical gardens existed not only in Tenochtitlan, but also in Chapultepec, Huastepec, Ixtapalapa, Penon, Tetzcoco and Atlixco. A profound knowledge of medicinal plants together with that of the human body helped Aztec doctors, known as ticitls, to produce cures from herbs, roots and barks, often in the form of dried plants which they ground to make medicines. These ticitls were also skilled surgeons who performed operations and used their plant remedies to speed healing.

‘When the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century, they marveled at the knowledge of the Aztecs and their use of medicinal plants to treat disease,’ Luis continued, describing how Francisco Guerra wrote a detailed account of Mexican medicine shortly after the Conquest in his work Aztec Science and Technology which was developed to a degree that led many educated Spaniards to believe it was equal to or superior to European medical knowledge, especially in the field of plants and herbs employed to care for the sick and their ailments.

However, magic and religious rituals were also part of the Aztec’s healing process and to a greater degree than in Old World religions that continued to see disease as a punishment for sins, invoking god and the saints for forgiveness.

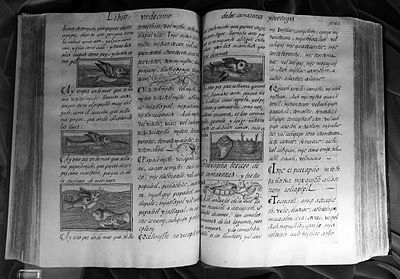

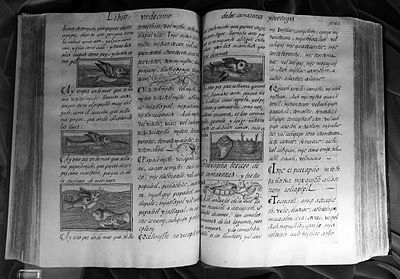

Francisco Guerra’s work was founded on two massive codices, first the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis and second La Historia Universal de las Cosas de Nueva España.

This considerable biological, medical and botanical base served Francisco Hernandez’s scientific expedition to Mexico undertaken during the period 1570-1577.

Of course, the use of magic and religious rituals conflicted with the teachings of the Catholic Church, the influence of which overwhelmed local cultural traditions and the treatment of illnesses using the knowledge and traditions of the Aztecs was condemned.

‘Today we know herbal concoctions for medicinal purposes have been used in many other civilisations,’ concluded Luis, ‘those of ancient Egypt, China, Babylon, Greece, and Rome. We should remember less than 2% of the world’s botanical resources have been exploited for bioactive molecules and this 2% is linked to a quarter of all prescription medicines!’

There was a round of solid applause and the participants were invited for refreshments in an adjoining reception space where drinks and snacks were served.

*

Amongst those at the bar was Arkady Demitriev who had flown into LA for the conference. He was registered as a Canadian academic—an expat from Mexico City. It was a role he occasionally used, speaking perfect American English and Latino Spanish.

Though he found the theme of the conference interesting, he was puzzled in the sense that it had nothing to do with Belize. That is until Gutierrez spoke about the Badianus and Sahagun codices, of which he knew nothing, however, when images of the codices were projected onto the screen he recalled the story he had been told on a visit to the archaeological site Palanque in the south of Mexico, of how two Russians had played a role in the research into the archaeological story of the Mayas.

First was Tatiana Proskouriakov, ‘Duchess’ to her family and ‘Tania’ to her friends. The second was Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, a Soviet linguist, who found the key to decipher the Maya script.

Knorozov, who was born in 1922, became a renowned Soviet linguist epigrapher and ethnographer. He gained international fame for the pivotal role his research played in the race to decipher the script.

Born into a family of Russian intellectuals in a village near Kharkiv, in the newly formed Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, Knorozov had been a bright and creative child. In 1940 at the age of 17, he left Kharkiv for Moscow. There in the capital of the Soviet Union he commenced as an undergraduate in the newly created Department of Ethnology at Lomonosov Moscow State University, where his friends recalled that he had been fascinated by writing systems and paleography, especially Egyptian hieroglyphs.

On Sunday, 22 June 1941, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, opening up hostilities along the Eastern Front. Knorozov was enrolled in the Red Army as an artillery spotter in 1944. Then, as the war Knorozov drew to an end, he entered Berlin during the final assault on the Nazi's last stronghold.

There, according to the oft recited story, Knorozov, in the aftermath of the battle, pulled a book from the flames that were engulfing the German National Library.

It was a rare edition that contained reproductions of the three famous Maya books— the Dresden, Madrid and Paris codices. At the end of the war Knorozov returned to Moscow where the book formed the basis for his pioneering research into the Maya script.

The truth was more prosaic, revealed by Knorozov, shortly before his death in 1999, to the Mayanist epigrapher Harri Kettunen:

‘Unfortunately it was a misunderstanding: I told the story to my colleague Michael Coe, but he didn’t get it right. There simply wasn’t any fire in the library. And the books that were in the library, were in boxes to be sent somewhere else. The fascist command had packed them, and since they didn’t have time to move them anywhere, they were simply taken to Moscow. I didn’t see any fire there.’

Further the ‘Codex’ was not a codex, but a rare edition of a book containing reproductions of three Maya codices—the Dresden, Madrid and Paris codices. As for National Library, it was in fact the Preußische Staatsbibliothek, the largest scientific library in Germany. During the war some 350,000 volumes destroyed and a further 300,000 disappeared, more precisely ending up in Soviet and Polish collections, and in particular in the Russian State Library in Moscow.

The facts show there wasn’t any fire at all and the books were already prepared for shipment to Moscow.

Worse still there was little evidence to show that Knorozov had even been in Berlin, according to his military records, his army unit was based close Moscow.

The truth is after the war, in 1945, he went on to complete his undergraduate studies at the MSU. His thesis on the Shamun Nabi Mausoleum and the associated oral and written tradition based on his fieldwork in Chorasmian in Uzbekistan, as a member of an archaeological-ethnographic expedition.

An aircraft of the Chorasmian Expedition in 1949 above the early medieval site of Adamli-kala in Uzbekistan

In 1949, he moved to St. Petersburg where he was appointed junior research fellow at the Museum of the Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR. About that time, Knorozov became fascinated by the question of Maya hieroglyphs. While studying the manuscript written by Diego de Landa, the Bishop of Yucatan, he realized that Landa’s alphabet of Maya hieroglyphs contained readings of several syllabic signs.

Knorozov then turned to the published Maya codices, identified the same signs in these manuscripts, and succeeded in deciphering new syllables and discovered that Maya writing was logo-syllabic.

*

The story of Tatianaovna Proskouriakoff, who contributed to breaking the code of the Mayan language, was much more fascinating. By the strangest of destinies she followed a path that led her to becoming one of the remarkable figures in the study of Mayan history. She was born at the beginning of 1909, in Czarist Russia, at Tomsk in Siberia, very far from the steaming jungles of Honduras.

With the start of the Great War everything changed, her father was commissioned by the New Russia government to oversee the production of armaments in the US bought by the czarist regime and the family was sent to New York.

They arrived in early 1916 and soon moved to Ohio. Then, in 1917, a series of events took place in Russia that were to lead to the October Revolution, starting with the abdication of the Czar, then the fall of the Kerenski government and finally the Bolsheviks seizure of power, at which point there was no question of the family returning to Russia.

After the Proskouriakoffs became US citizens, Tania was enrolled at Pennsylvania State College to study architecture, where she graduated just after the Crash of 29 and the start of the Great Depression.

During the early 1930s, Tania volunteered for drafting work at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and was sent to undertake the work of drawing the materials collected on the Piedras Negras expeditions along the Usumacinta River on the border between Mexico and Guatemala.

In 1930, aerial photographs from Charles Lindbergh’s flight over the Maya region had shown hitherto unmapped archaeological sites in the jungles. As a result the museum sent a team to explorer the sites.

Then, Piedras Negras was chosen for the museum’s first major Maya project, where the glyphs on the sculptures led to Tania Proskouriakoff deciphering the texts.

*

The next day immediately after breakfast Anna and Dee left Santa Monica for Palm Springs, a pleasant two hour drive, arriving in the mid-morning desert sunshine. Luis together with Angela Valladares was already waiting to give them guided a tour of the botanical gardens.

Anna was eager to see the real plants after having spent the previous weeks looking at illustrations in the codex.

‘Tell us about how plants are collected, what kinds of plants grow in the desert, how the desert varies from one place to another,’ she asked Luis.

‘First I must tell you Greater Palm Springs is a plant-lover’s paradise, when people think of a desert they think of cacti, they also think of a grim desolate wasteland, rattlesnakes and the burning heat of the sun, that of course exists, but the real desert is full of life, sunshine, gentle winds, incredible landscapes, thorny plants that have survived millions of years, adapting to heat and drought, bursting into flower when rain does fall.’

‘Fantastic,’ Anna exclaimed as he led them into one of the glasshouses filled with flowering plants.

‘Besides our greenhouses and gardens here, we have a three thousand acre conservation area with plants of every kind from different geographical regions, including the Colorado, Mojave and Chihuahua deserts.’

‘We also have trees and shrubs, like Yucca brevifolia that’s the Joshua tree from the Mojave, Yucca, Creosote bushes and Ocotillo from the Colorado, or palms like the Washingtonia filifera.’

Creosote, that recalled something in the Wallace Codex.

‘Creosote, that’s a very old plant,’ said Anna.

‘If you mean it lives a longtime, you’re right. We'll see it tomorrow. I promised you some adventure and we’ll start exploring tomorrow, commencing with our conservation area which lies within the Joshua Tree National Park. There we can explore the biosphere, its ecosystems and multiple niches and overnight in our desert lodge.’

Back in their hotel Anna checked out her translation of the Wallace Codex on her laptop. The creosote bush was known by the Aztecs for its medicinal properties, they used it to treat chicken pox, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, menstrual pain in women, snake bites, colds, diabetes, skin sores, arthritis, sinusitis, gout, anemia, fungal infections, and cancer.

That sounded like a snake oil cure-all remedy, in fact many of the plants in the codex were claimed to be miraculous cure-alls. But there was something else, something more sinister—the leaves and sap of the creosote bush were used by the priests, mixed with the blood of sacrificial victims, as a symbolic offering by the emperor to appease Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, sun, human sacrifice, the patron of the city of Tenochtitlan.

Over dinner she recalled the creosote bush, and pushed Luis for more details.

‘It grows in the Mojave, we’ll see it in the conservation area,’ he replied, amused by her insistence. ‘Scientifically it’s called Larrea tridentata, a desert shrub, a perennial flowering bush. You can always spot it by the yellow flowers and its pleasantly pungent perfume when it rains.

‘In fact there are several varieties, those in the Mojave Desert which have 78 chromosomes, then Sonoran Desert variety which has 52 chromosomes, and those in the Chihuahuan Desert with only 26.

‘They can live thousands of years, the oldest, the King Clone colony, is believed to be an incredible 11,000 years old. It can also survive long periods without water. It’s a native of the Mojave, a desert chaparral ecosystem, to the north of us.’

‘It’s described on one of your sheets Anna,’ said Angela.

Anna nodded.

After diner back in their hotel Anna checked the medicinal properties of the Larrea tridentata. She read the creosote bush was rich in simple bisphenyl lignans and tricyclic lignans known as cyclolignans. Compounds that were shown to be powerful agents against certain viruses, age related diseases and aging in general.

It was also rich in Nordihydroguaiaretic, NDGA, a phenolic antioxidant found in its leaves and twigs, which had a long history of being used as a traditional medicinal by the Native Americans and Mexicans.

*

The next morning as they set off for the conservation area, unknown to them they were followed by Arkady Demitriev driving a passepartout rental SUV. He had not slept well that night Sedov’s friends were furious, their Dominican passports, without which they could not travel to the EU, were not forthcoming. Dominica—known as the Nature Isle of the Caribbean, besides being a small sparsely populated island, between the French islands of Martinique and Guadalupe, known for its crystal clear rivers, and its spectacular mountain landscape cloaked in the Caribbean's last remaining primary tropical rainforest—was seeking to establish itself as an offshore tax haven, offering in addition to financial services, investor citizenship.

The fault lay in the fact that Wallace was dead, killed before he could complete the formalities, in addition the company set-up by Simmonds had not been able to transferred the funds, he too had been killed in the unfortunate accident caused by the fools Demitriev had sent to question him.

The bad news was compounded as Cyprus announced the scrapping of its investor citizenship scheme and threatened to revoke citizenship of certain passport holders suspected of wrongdoings.

The news came after a top Cyprus official and the parliamentary speaker were filmed in undercover sting, promising full backing for a passport application from a fictitious Chinese investor who had supposedly been convicted of money laundering.

The so-called ‘golden passport’ scheme, which had been riddled with corruption and kickbacks, automatically granted holders of Cyprus citizenship and passports access to the entire 27-member European Union, a scheme that had issued more than 4,000 earning billions of euros for the Cyprus government, their crooked politicians and middlemen.

Cyprus, a member state of the European Union, had long been criticism by the European Commission for trafficking EU citizenship, especially to Russians, for financial gains.

Now, in addition to scrapping the scheme, the Cyprus Security and Exchange Commission recommended that authorities revoke citizenship granted to several wrongdoers—individuals who submitted forged documents in their application, amongst them were Sedov’s friends.

Demitriev put aside those worries as he stalked his prey. The sun was now high as he watched Anna Basurko and her friends through his binoculars. He was crouched on a bluff about half a mile to the west as they arrived at a lodge situated on the edge of a fenced off botanical conservation reserve. According to a panel at the gate, the property belonged to a company called Phytotech with a contact address in Palm Springs.

The Russian had spent most of the morning observing them driving around, stopping here and there, looking at plants and trees. It was a strange outing for an archaeologist and a writer, as strange as their attendance at the Getty Center conference.