XIII: KOSHTRA BELORN

HOW THE LORD JUSS ACCOMPLISHED AT LENGTH HIS DREAM’S BEHEST, TO INQUIRE IN KOSHTRA BELORN; AND WHAT MANNER OF ANSWER HE RECEIVED.

THAT night they spent safely, by favour of the Gods, under the highest crags of Koshtra Pivrarcha, in a sheltered hollow piled round with snow. Dawn came like a lily, saffron-hued, smirched with smoke-gray streaks that slanted from the north. The great peaks stood as islands above a main of level cloud, out of which the sun walked flaming, a ball of red-gold fire. An hour before his face appeared, the Demons and Mivarsh were roped and started on their eastward journey. Ill to do with as was the crest of the great north buttress by which they had climbed the mountain, seven times worse was this eastern ridge, leading to Koshtra Belorn. Leaner of back it was, flanked by more profound abysses, deeplier gashed, too treacherous and too sudden in its changes from sure rock to rotten and perilous: piled with tottering crags, hung about with cornices of uncertain snow, girt with cliffs smooth and holdless as a castle wall. Small marvel that it cost them thirteen hours to come down that ridge. The sun wheeled towards the west when they reached at length that frozen edge, sharp as a sickle, that was in the Gates of Zimiamvia. Weary they were, and ropeless; for by no means else might they come down from the last great tower save by the rope made fast from above. A fierce north-easter had swept the ridges all day, bringing snow-storms on its wings. Their fingers were numbed with cold, and the beards of Lord Brandoch Daha and Mivarsh Faz stiff with ice.

Too weary to halt, they set forth again, Juss leading. It was many hundred paces along that ice-edge, and the sun was near setting when they stood at last within a stone’s throw of the cliffs of Koshtra Belorn. Since before noon avalanches had thundered ceaselessly down those cliffs. Now, in the cool of the evening, all was still. The wind was fallen. The deep blue sky was without a cloud. The fires of sunset crept down the vast white precipices before them till every ledge and fold and frozen pinnacle glowed pink colour, and every shadow became an emerald. The shadow of Koshtra Pivrarcha lay cold across the lower stretches of the face on the Zimiamvian side. The edge of that shadow was as the division betwixt the living and the dead.

“What dost think on?” said Juss to Brandoch Daha, that leaned upon his sword surveying that glory.

Brandoch Daha started and looked on him. “Why,” said he, “on this: that it is likely thy dream was but a lure, sent thee by the King to tempt us on to mighty actions reserved for our destruction. On this side at least ’tis very certain there lieth no way up Koshtra Belorn.”

“What of the little martlet,” said Juss, “who, whiles we were yet a great way off, flew out of the south to greet us with a gracious message?”

“Well if it were not a devil of his,” said Brandoch Daha.

“I will not turn back,” said Juss. “Thou needest not to come with me.” And he turned again to look on those frozen cliffs.

“No?” said Brandoch Daha. “Nor thou with me. Thou’lt make me angry if thou wilt so vilely wrest my words. Only fare not too securely; and let that axe still be ready in thine hand, as is my sword, for kindlier work than step-cutting. And if thou embrace the hope to climb her by this wall before us, then hath the King’s enchantery made thee fey.”

By then was the sun gone down. Under the wings of night uplifted from the east, the unfathomable heights of air turned a richer blue; and here and there, most dim and hard to see, throbbed a tiny point of light: the greater stars opening their eyelids to the gathering dark. Gloom crept upward, brimming the valleys far below like a rising tide of the sea. Frost and stillness waited on the eternal night to resume her reign. The solemn cliffs of Koshtra Belorn stood in tremendous silence, death-pale against the sky.

Juss came backward a step along the ridge, and laying his hand on Brandoch Daha’s, “Be still,” he said, “and behold this marvel.” A little up the face of the mountain on the Zimiamvian side, it was as if some leavings of the after-glow had been entangled among the crags and frozen curtains of snow. As the gloom deepened, that glow brightened and spread, filling a rift that seemed to go into the mountain.

“It is because of us,” said Juss, in a low voice. “She is afire with expectation of us.”

No sound was there save of their breath coming and going, and of the strokes of Juss’s axe, and of the chips of ice chinking downwards into silence as he cut their way along the ridge. And ever brighter, as night fell, burned that strange sunset light above them. Perilous climbing it was for fifty feet or more from the ridge, for they had no rope, the way was hard to see, and the rocks were steep and iced and every ledge deep in snow. Yet came they safe at length up by a steep short gully to the gully’s head where it widened to that rift of the wondrous light. Here might two walk abreast, and Lord Juss and Lord Brandoch Daha took their weapons and entered abreast into the rift. Mivarsh was fain to call to them, but he was speechless. He came after, close at their heels like a dog.

For some way the bed of the cave ran upwards, then dipped at a gentle slope deep into the mountain. The air was cold, yet warm after the frozen air without. The rose-red light shone warm on the walls and floor of that passage, but none might say whence it shone. Strange sculptures glimmered overhead, bull-headed men, stags with human faces, mammoths, and behemoths of the flood: vast forms and uncertain carved in the living rock. For hours Juss and his companions pursued their way, winding downward, losing all sense of north and south. Little by little the light faded, and after an hour or two they went in darkness: yet not in utter darkness, but as of a starless night in summer where all night long twilight lingers. They went a soft pace, for fear of pitfalls in the way.

After a while Juss halted and sniffed the air. “I smell new-mown hay,” he said, “and flower-scents. Is this my fantasy, or canst thou smell them too?”

“Ay, and have smelt it this half-hour past,” answered Brandoch Daha; “also the passage wideneth before us, and the roof of it goeth higher as we journey.”

“This,” said Juss, “is a great wonder.”

They fared onward, and in a while the slope slackened, and they felt loose stones and grit beneath their feet, and in a while soft earth. They bent down and touched the earth, and there was grass growing, and night-dew on the grass, and daisies folded up asleep. A brook tinkled on the right. So they crossed that meadow in the dark, until they stood below a shadowy mass that bulked big above them. In a blind wall so high the top was swallowed up in the darkness a gate stood open. They crossed that threshold and passed through a paved court that clanked under their tread. Before them a flight of steps went up to folding doors under an archway.

Lord Brandoch Daha felt Mivarsh pluck him by the sleeve. The little man’s teeth were chattering together in his head for terror. Brandoch Daha smiled and put an arm about him. Juss had his foot on the lowest step.

In that instant came a sound of music playing, but of what instruments they might not guess. Great thundering chords began it, like trumpets calling to battle, first high, then low, then shuddering down to silence; then that great call again, sounding defiance. Then the keys took new voices, groping in darkness, rising to passionate lament, hovering and dying away on the wind, until nought remained but a roll as of muffled thunder, long, low, quiet, but menacing ill. And now out of the darkness of that induction burst a mighty form, three ponderous blows, as of breakers that plunge and strike on a desolate shore; a pause; those blows again; a grinding pause; a rushing of wings, as of Furies steaming up from the pit; another flight of them dreadful in its deliberation; then a wild rush upward and a swooping again; confusion of hell, raging serpents blazing through night sky. Then on a sudden out of a distant key, a sweet melody, long-drawn and clear, like a blaze of low sunshine piercing the dust-clouds above a battle-field. This was but an interlude to the terror of the great main theme that came in tumultuous strides up again from the deeps, storming to a grand climacteric of fury and passing away into silence. Now came a majestic figure, stately and calm, born of that terror, leading to it again: battlings of these themes in many keys, and at last the great triple blow, thundering in new strength, crushing all joy and sweetness as with a mace of iron, battering the roots of life into a general ruin. But even in the main stride of its outrage and terror, that great power seemed to shrivel. The thunder-blasts crashed weaklier, the harsh blows rattled awry, and the vast frame of conquest and destroying violence sank down panting, tottered and rumbled ingloriously into silence.

Like men held in a trance those lords of Demonland listened to the last echoes of the great sad chord where that music had breathed out its heart, as if the very heart of wrath were broken. But this was not the end. Cold and serene as some chaste virgin vowed to the Gods, with clear eyes which see nought below high heaven, a quiet melody rose from that grave of terror. Weak it seemed at first, a little thing after that cataclysm; a little thing, like spring’s first bud peeping after the blasting reign of cold and ice. Yet it walked undismayed, gathering as it went beauty and power. And on a sudden the folding doors swung open, shedding a flood of radiance down the stairs.

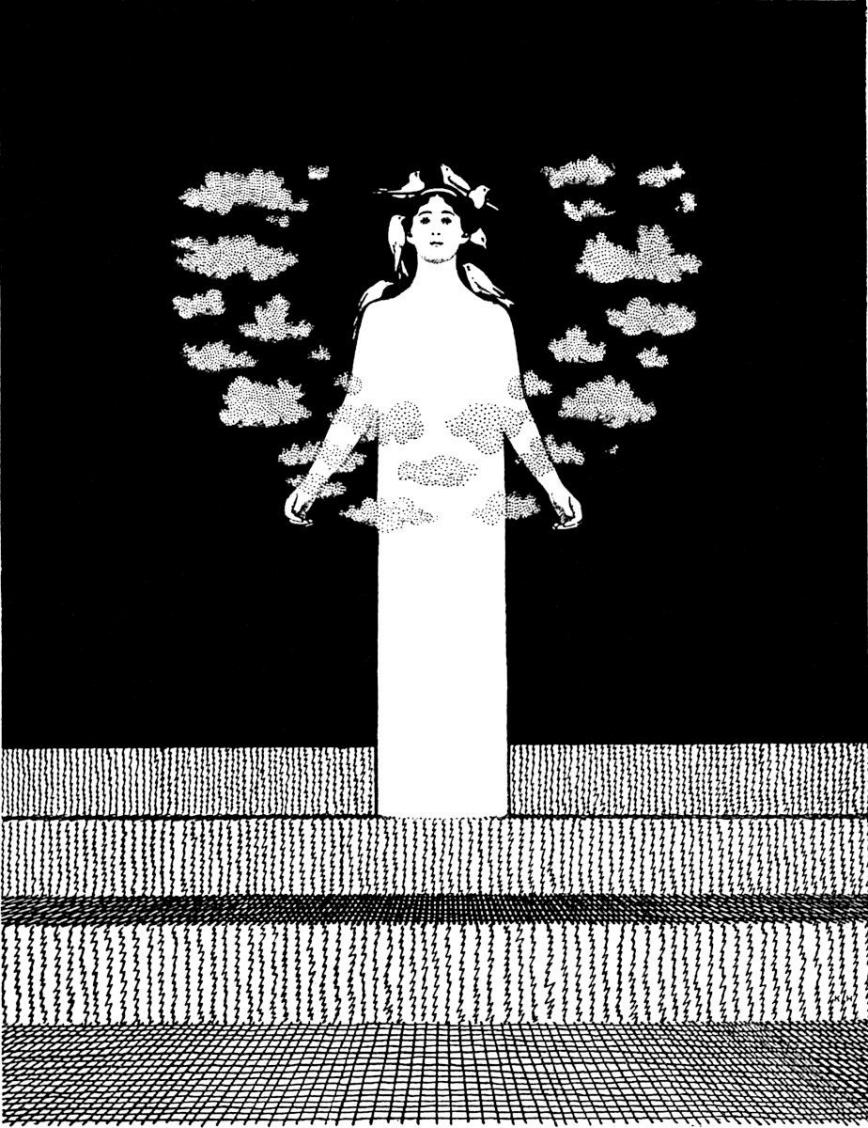

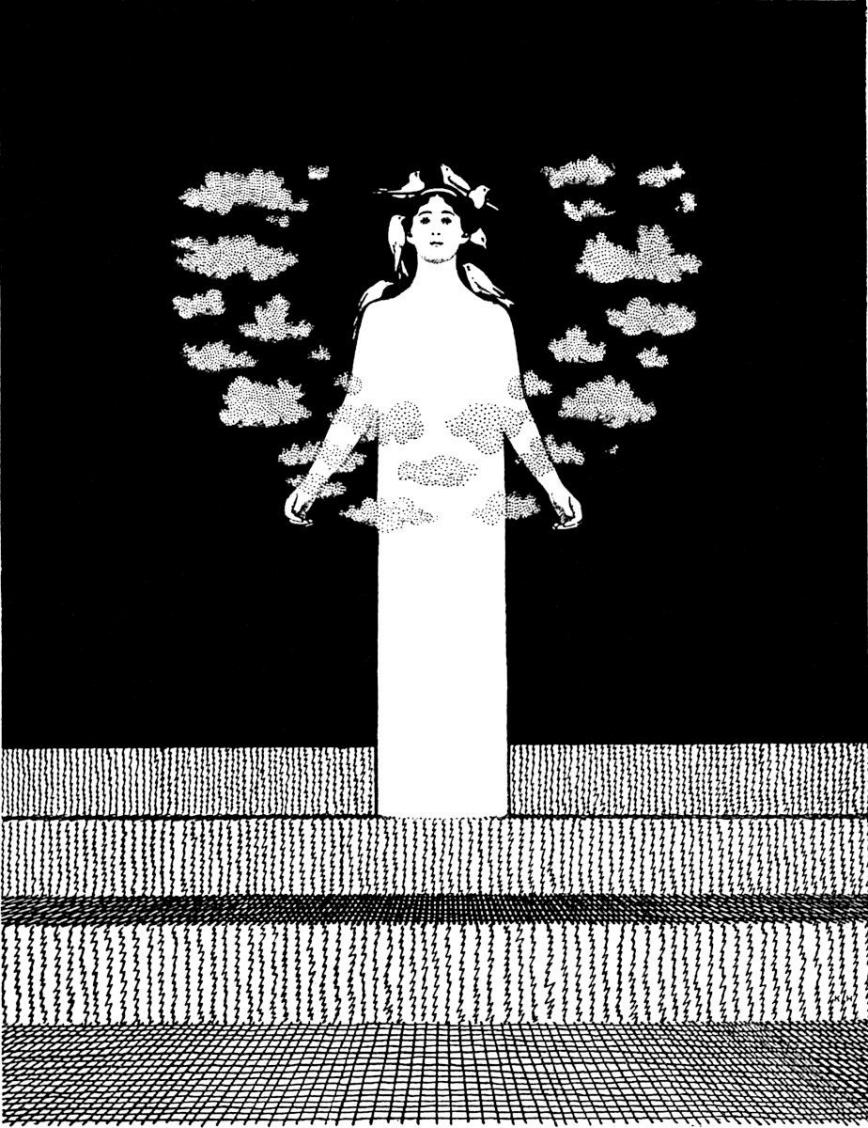

Lord Juss and Lord Brandoch Daha watched, as men watch for a star to rise, that radiant portal. And like a star indeed, or like the tranquil moon appearing, they beheld after a while one crowned like a Queen with a diadem of little clouds that seemed stolen from the mountain sunset, scattering soft beams of rosy brightness. She stood alone under that mighty portico with its vast shadowy forms of winged lions in shining stone black as jet. Youthful she seemed, as one that hath but just bidden adieu to childhood, with grave sweet lips and grave black eyes and hair like the night. Little black martlets perched on her either shoulder, and a dozen more skimmed the air above her head, so swift of wing that scarcely the eye might follow them. Meantime, that delicate and simple melody mounted from height to height, until in a while it burned with all the fires of summer, burned as summer to the uttermost ember, fierce and compulsive in its riot of love and beauty. So that, before the last triumphant chords died down in silence, that music had brought back to Juss all the glories of the mountains, the sunset fires on Koshtra Belorn, the first great revelation of the peaks from Morna Moruna; and over all these, as the spirit of that music to the eye made manifest, the image of that Queen so blessed-fair in her youth and her clear brow’s sweet solemn respect and promise: in every line and pose of her fair form, virginal dainty as a flower, and kindled from withinward as never flower was with that divinity before the face of which speech and song fall silent and men may but catch their breath and worship.

When she spoke, it was with a voice like crystal: “Thanks be and praise to the blessed Gods. For lo, the years depart, and the fated years bring forth as the Gods ordain. And ye be those that were for to come.”

Surely those great lords of Demonland stood like little boys before her. She said again, “Are not ye Lord Juss and Lord Brandoch Daha of Demonland, come up to me by the way banned to all mortals else, come up into Koshtra Belorn?”

Then answered Lord Juss for them both and said, “Surely, O Queen Sophonisba, we be they thou namest.”

Now the Queen carried them into her palace, and into a great hall where was her throne and state. The pillars of the hall were as vast towers, and there were galleries above them, tier upon tier, rising higher than sight could reach or the light of the gentle lamps in their stands that lighted the tables and the floor. The walls and the pillars were of a sombre stone unpolished, and on the walls strange portraitures: lions, dragons, nickers of the sea, spread-eagles, elephants, swans, unicorns, and other, lively made and richly set forth with curious colours of painting: all of giant size beyond the experience of human kind, so that to be in that hall was as it were to shelter in a small spot of light and life, canopied, vaulted, and embraced by the circumambient unknown.

The Queen sate on her throne that was bright like the face of a river ruffled with wind under a silver moon. Save for those little martlets she was unattended. She made those lords of Demonland sit down before her face, and there were brought forth by the agency of unseen hands tables before them and precious dishes filled with unknown viands. And there played a soft music, made in the air by what unseen art they knew not.

The Queen said, “Behold, ambrosia which the Gods do eat and nectar which they drink; on which meat and wine myself do feed, by the bounty of the blessed Gods. And the savour thereof wearieth not, and the glow thereof and the perfume thereof dieth not for ever.”

So they tasted of the ambrosia, that was white to look on and crisp to the tooth and sweet, and being eaten revived strength in the body more than a surfeit of bullock’s flesh, and of the nectar that was all afoam and coloured like the inmost fires of sunset. Surely somewhat of the peace of the Gods was in that nectar divine.

The Queen said, “Tell me, why are ye come?”

Juss answered, “Surely there was a dream sent me, O Queen Sophonisba, through the gate of horn, and it bade me inquire hither after him I most desire, for want of whom my whole soul languisheth in sorrow this year gone by: even after my dear brother, the Lord Goldry Bluszco.”

His words ceased in his throat. For with the speaking of that name the firm fabric of that palace quivered like the leaves of a forest under a sudden squall. Colour went from the scene, like the blood chased from a man’s face by fear, and all was of a pallid hue, like the landscape which one beholds of a bright summer day after lying with eyes closed for a space face-upward under the blazing sun: all gray and cold, the warm colours burnt to ashes. Withal, followed the appearance of hateful little creatures issuing from the joints of the paving stones and the great blocks of the walls and pillars: some like grasshoppers with human heads and wings of flies, some like fishes with stings in their tails, some fat like toads, some like eels a-wriggling with puppy-dogs’ heads and asses’ ears: loathly ones, exiles of glory, scaly and obscene.

The horror passed. Colour returned. The Queen sat like a graven statue, her lips parted. After a while she said with a shaken voice, low and with downcast eyes, “Sirs, you demand of me a very strange matter, such as wherewith never hitherto I have been acquainted. As you are noble, I beseech you speak not that name again. In the name of the blessed Gods, speak it not again.”

Lord Juss was silent. Nought good were his thoughts within him.

In due time a little martlet by the Queen’s command brought them to their bed-chambers. And there in great beds soft and fragrant they went to rest.

IN KOSHTRA BELORN.

Juss waked long in the doubtful light, troubled at heart. At length he fell into a troubled sleep. The glimmer of the lamps mingled with his dreams and his dreams with it, so that scarce he wist whether asleep or waking he beheld the walls of the bed-chamber dispart in sunder, disclosing a prospect of vast paths of moonlight, and a solitary mountain peak standing naked out of a sea of cloud that gleamed white beneath the moon. It seemed to him that the power of flight was upon him, and that he flew to that mountain and hung in air beholding it near at hand, and a circle as the appearance of fire round about it, and on the summit of the mountain the likeness of a burg or citadel of brass that was green with eld and surface-battered by the frosts and winds of ages. On the battlements was the appearance of a great company both men and women, never still, now walking on the wall with hands lifted up as in supplication to the crystal lamps of heaven, now flinging themselves on their knees or leaning against the brazen battlements to bury their faces in their hands, or standing at gaze as night-walkers gazing into the void. Some seemed men of war, and some great courtiers by their costly apparel, rulers and kings and kings’ daughters, grave bearded counsellors, youths and maidens and crowned queens. And when they went, and when they stood, and when they seemed to cry aloud bitterly, all was noiseless even as the tomb, and the faces of those mourners pallid as a dead corpse is pallid.

Then it seemed to Juss that he beheld a keep of brass flat-roofed standing on the right, a little higher than the walls, with battlements about the roof. He strove to cry aloud, but it was as if some devil gripped his throat stifling him, for no sound came. For in the midst of the roof, as it were on a bench of stone, was the appearance of one reclining; his chin resting in his great right hand, his elbow on an arm of the bench, his cloak about him gorgeous with cloth of gold, his ponderous two-handed sword beside him with its heart-shaped ruby pommel darkly resplendent in the moonlight. Nought otherwise looked he than when Juss last beheld him, on their ship before the darkness swallowed them; only the ruddy hues of life seemed departed from him, and his brow seemed clouded with sorrow. His eye met his brother’s, but with no look of recognition, gazing as if on some far point in the deeps beyond the star-shine. It seemed to Juss that even so would he have looked to find his brother Goldry as he now found him; his head unbent for all the tyranny of those dark powers that held him in captivity: keeping like a God his patient vigil, heedless alike of the laments of them that shared his prison and of the menace of the houseless night about him.

The vision passed; and Lord Juss perceived himself in his bed again, the cold morning light stealing between the hangings of the windows and dimming the soft radiance of the lamps.

•••••

Now for seven days they dwelt in that palace. No living thing they encountered save only the Queen and her little martlets, but all things desirous were ministered unto them by unseen hands and all royal entertainment. Yet was Lord Juss heavy at heart, for as often as he would question the Queen of Goldry, so she would ever put him by, praying him earnestly not a second time to pronounce that name of terror. At last, walking with her alone in the cool of the evening on a trodden path of a meadow where asphodel grew and other holy flowers beside a quiet stream, he said, “So it is, O Queen Sophonisba, that when first I came hither and spake with thee I well thought that by thee my matter should be well sped. And didst not thou then promise me thy goodness and grace from thee thereafter?”

“This is very true,” said the Queen.

“Then why,” said he, “when I would question thee of that I make most store of, wilt thou always daff me and put me by?”

She was silent, hanging her head. He looked sidelong for a minute at her sweet profile, the grave clear lines of her mouth and chin. “Of whom must I inquire,” he said, “if not of thee, which art Queen in Koshtra Belorn and must know this thing?”

She stopped and faced him with dark eyes that were like a child’s for innocence and like a God’s for splendour. “My lord, that I have put thee off, ascribe it not to evil intent. That were an unnatural part indeed in me unto you of Demonland who have fulfilled the weird and set me free again to visit again the world of men which I so much desire, despite all my sorrows I there fulfilled in elder time. Or shall I forget you are at enmity with the wicked house of Witchland, and therefore doubly pledged my friends?”

“That the event must prove, O Queen,” said Lord Juss.

“O saw ye Morna Moruna?” cried she. “Saw ye it in the wilderness?” And when he looked on her still dark and mistrustful, she said, “Is this forgot? And methought it should be mention and remembrance made thereof unto the end of the world. I pray thee, my lord, what age art thou?”

“I have looked upon this world,” answered Lord Juss, “for thrice ten years.”

“And I,” said the Queen, “but seventeen summers. Yet that same age had I when thou wast born, and thy grandsire before thee, and his before him. For the Gods gave me youth for ever more, when they brought me hither after the realm-rape that befell our house, and lodged me in this mountain.”

She paused, and stood motionless, her hands clasped lightly before her, her head bent, her face turned a little away so that he saw only the white curve of her neck and her cheek’s soft outline. All the air was full of sunset, though no sun was there, but a scattered splendour only, shed from the high roof of rock that was like a sky above them self-effulgent. Very softly she began again to speak, the crystal accents of her voice sounding like the faint notes of a bell borne from a great way off on the quiet air of a summer evening. “Surely time past is gone by like a shadow since those days, when I was Queen in Morna Moruna, dwelling there with my lady mother and the princes my cousins in peace and joy. Until Gorice III. came out of the north, the great King of Witchland, desiring to explore these mountains, for his pride sake and his insolent heart; which cost him dear. ’Twas on an evening of early summer we beheld him and his folk ride over the flowering meadows of the Moruna. Nobly was he entertained by us, and when we knew what way he meant to go, we counselled him turn back, and the mantichores must tear him if he went. But he mocked at our advisoes, and on the morrow departed, he and his, by way of Omprenne Edge. And never again were they seen of living man.

“That had been small loss; but hereof there befell a great and horrible mischief. For in the spring of the year came Gorice IV. with a great army out of waterish Witchland, saying with open mouth of defamation that we were the dead King’s murtherers: we that were peaceful folk, and would not entertain an action should call us villain for all the wealth of Impland. In the night they came, when all we save the sentinels upon the walls were in our beds secure in a quiet conscience. They took the princes my cousins and all our men, and before our eyes most cruelly murthered them. So that my mother seeing these things fell suddenly into deadly swoonings and was presently dead. And the King commanded them burn the house with fire, and he brake down the holy altars of the Gods, and defiled their high places. And unto me that was young and fair to look on he gave this choice, to go with him and be his slave, other else to be cast down from the Edge and all my bones be broken. Surely I chose this rather. But the Gods, that do help every rightful true cause, made light my fall, and guided me hither safe through all perils of height and cold and ravening beasts, granting me youth and peaceful days for ever, here on the borderland between the living and the dead.

“And the Gods blew upon all the land of the Moruna in the fire of their wrath, to make it desolate, and man and beast cut off therefrom, for a witness of the wicked deeds of Gorice the King, even as Gorice the King made desolate our little castle and our pleasant places. The face of the land was lifted up to high airs where frosts do dwell, so that the cliffs of Omprenne Edge down which ye came are ten times the height they were when Gorice III. came down them. So was an end of flowers on the Moruna, and an end there of spring and of summer days for ever.”

The Queen ceased speaking, and Lord Juss was silent for a space, greatly marvelling.

“Judge now,” said she, “if your foes be not my foes. It is not hidden from me, my lord, that you deem me but a lukewarm friend and no helper at all in your enterprise. Yet have I ceased not since ye were here to search and to inquire, and sent my little martlets west and east and south and north after tidings of him thou namedst. They are swift, even as wingy thoughts circling the stablished world; and they returned to me on weary wings, yet with never a word of thy great kinsman.”

Juss looked at her eyes that were moist with tears. Truth sat in them like an angel. “O Queen,” he cried, “why need thy little minions scour the world, when my brother is here in Koshtra Belorn?”

She shook her head, saying, “This I will swear to thee, there hath no mortal come up into Koshtra Belorn save only thee and thy companions these two hundred years.”

But Juss said again, “My brother is here in Koshtra Belorn. Mine eyes beheld him that first night, hedged about with fires. And he is held captive on a tower of brass on a peak of a mountain.”

“There be no mountains here,” said she, “save this in whose womb we have our dwelling.”

“Yet so I beheld my brother,” said Juss, “under the white beams of the full moon.”

“There is no moon here,” said the Queen.

So Lord Juss rehearsed to her his vision of the night, telling her point to point of everything. She harkened gravely, and when he had done, trembled a little and said, “This is a mystery, my lord, beyond my resolution.”

She fell silent awhile. Then she began to say in a hushed voice, as if the very words and breath might breed some dreadful matter: “Taken up in a sending maleficial by King Gorice XII. So it hath ever been, that whensoever there dieth one of the house of Gorice there riseth up another in his stead, and so from strength to strength. And death weakeneth not this house of Witchland, but like the dandelion weed being cut down and bruised it springeth up the stronger. Dost thou know why?”

He answered, “No.”

“The blessed Gods,” said she, speaking yet lower, “have shown me many hidden matters which the sons of men know not neither imagine. Behold this mystery. There is but One Gorice. And by the favour of heaven (that moveth sometimes in a manner our weak judgement seeketh in vain to justify) this cruel and evil One, every time whether by the sword or in the fulness of his years he cometh to die, departeth the living soul and spirit of him into a new and sound body, and liveth yet another lifetime to vex and to oppress the world, until that body die, and the next in his turn, and so continually; having thus in a manner life eternal.”

Juss said, “Thy discourse, O Queen Sophonisba, is in a strain above mortality. This is a great wonder thou tellest me; whereof some little part I guessed aforetime, but the main I knew not. Rightfully, having such a timeless life, this King weareth on his thumb that worm Ouroboros which doctors have from of old made for an ensample of eternity, whereof the end is ever at the beginning and the beginning at the end for ever more.”

“See then the hardness of the thing,” said the Queen. “But I forget not, my lord, that thou hast a matter nearer thine heart than this: to set free him (name him not!) concerning whom thou didst inquire of me. Touching this, know it for thy comfort, some ray of light I see. Question me no more till I have made trial thereof, lest it prove but a false dawn. If it be as I think, ’tis a trial yet abideth thee should make the stoutest blench.”