Issues with Civilian Use of Drones

UASs are aircraft that do not carry a pilot aboard, but instead operate on pre-programmed routes or are manually controlled by following commands from pilot-operated ground control stations. Unauthorized UAS operations have, in some instances, compromised safety. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 directed FAA to take actions to safely integrate UASs into the national airspace. In response, FAA developed a phased approach to facilitate integration and established test sites among other things.

GAO was asked to review FAA's progress in integrating UASs. The August 2015 report addresses (1) the status of FAA's progress toward safe integration of UASs into the national airspace, (2) research and development support from FAA's test sites and other resources, and (3) how other countries have progressed toward UAS integration into their airspace for commercial purposes. GAO reviewed and analyzed FAA's integration- planning documents; interviewed officials from FAA and UAS industry stakeholders; and met with the civil aviation authorities from Australia, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom. These countries were selected based on several factors including whether they have regulatory requirements for commercial UASs, operations beyond the view of the pilot, and whether non-military UAS are allowed to operate in the airspace.

The GAO found that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has progressed toward its goal of seamlessly integrating unmanned aerial system (UAS) flights into the national airspace. FAA has issued its UAS Comprehensive Plan and UAS Integration Roadmap which provide broad plans for integration. However, according to FAA, it is working with MITRE to develop a foundation for an implementation plan; FAA then expects to enact a plan by December 2015. While FAA still approves all UAS operations on a case-by-case basis, in recent years it has increased approvals for UAS operations. Specifically, the total number of approvals for UAS operations has increased each year since 2010, and over the past year has included approvals for commercial UAS operations for the first time. In addition, FAA has issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that proposes regulations for small UASs (less than 55 pounds).

The FAA's six designated test sites have become operational but have had to address various challenges during the process. The designated test sites became operational in 2014, and as of March 2015, over 195 test flights had taken place. These flights provide operations and safety data to FAA in support of UAS integration. In addition, FAA has provided all test sites with a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization allowing small UAS operations below 200 feet anywhere in the United States. However, during the first year of operations, the test sites faced some challenges. Specifically, the test sites sought additional guidance regarding the type of research they should conduct. According to FAA, it cannot direct the test sites, which receive no federal funding, to conduct specific research. However, FAA did provide a list of potential research areas to the test sites to provide some guidance on areas for research. FAA has conducted other UAS research through agreements with MITRE and some universities, and in May 2015 named the location of the UAS Center of Excellence—a partnership among academia, industry, and government conducting additional UAS research. Unlike FAA's agreements with the test sites, many of these arrangements have language specifically addressing the sharing of research and data.

Around the world, countries have been allowing UAS operations in their airspace for purposes such as agricultural applications and aerial surveying. Unlike in the United States, countries GAO examined—Australia, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom—have well-established UAS regulations. Also, Canada and France currently allow more commercial operations than the United States. While the United States had not finalized UAS regulations, the provisions of FAA's proposed rules are similar to those in the countries GAO examined. However, FAA may not issue a final rule for UASs until late 2016 or early 2017, and rules in some of these countries continue to evolve. Meanwhile, unlike under FAA's proposed rule, Canada has created exemptions for commercial use of small UASs in two categories that allow operations without a government-issued certification, and France and Australia are approving limited beyond line-of-sight operations. Similar to the United States, other countries are facing technology shortfalls, such as the ability to detect and avoid other aircraft and obstacles, as well as unresolved issues involving limited spectrum that limit the progress toward full integration of UASs into the airspace in these countries.

(Link: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-610)

Busting Myths about the FAA and Unmanned Aircraft

There are a lot of misconceptions and misinformation about unmanned aircraft system (UAS) regulations. Here are some common myths and the corresponding facts.

Myth #1: The FAA doesn't control airspace below 400 feet

Fact—The FAA is responsible for the safety of U.S. airspace from the ground up. This misperception may originate with the idea that manned aircraft generally must stay at least 500 feet above the ground

Myth #2: Commercial UAS flights are OK if I'm over private property and stay below 400 feet.

Fact—The FAA published a Federal Register notice (PDF) in 2007 that clarified the agency’s policy: You may not fly a UAS for commercial purposes by claiming that you’re operating according to the Model Aircraft guidelines (below 400 feet, 3 miles from an airport, away from populated areas.) Commercial operations are only authorized on a case-by-case basis. A commercial flight requires a certified aircraft, a licensed pilot and operating approval. To date, only one operation has met these criteria, using Insitu's ScanEagle, and authorization was limited to the Arctic.( http://www.faa.gov/news/updates/?newsId=73981)

Myth #3: Commercial UAS operations are a “gray area” in FAA regulations.

Fact—There are no shades of gray in FAA regulations. Anyone who wants to fly an aircraft—manned or unmanned—in U.S. airspace needs some level of FAA approval. Private sector (civil) users can obtain an experimental airworthiness certificate to conduct research and development, training and flight demonstrations. Commercial UAS operations are limited and require the operator to have certified aircraft and pilots, as well as operating approval. To date, only two UAS models (the Scan Eagle and Aerovironment’s Puma) have been certified, and they can only fly in the Arctic. Public entities (federal, state and local governments and public universities) may apply for a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) The FAA reviews and approves UAS operations over densely-populated areas on a case-by-case basis.

Flying model aircraft solely for hobby or recreational reasons does not require FAA approval. However, hobbyists are advised to operate their aircraft in accordance with the agency's model aircraft guidelines (see Advisory Circular 91-57). In the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (Public Law 112-95, Sec 336), Congress exempted model aircraft from new rules or regulations provided the aircraft are operated "in accordance with a community-based set of safety guidelines and within the programming of a nationwide community-based organization."

The FAA and the Academy of Model Aeronautics recently signed a first-ever agreement that formalizes a working relationship and establishes a partnership for advancing safe model UAS operations. This agreement also lays the ground work for enacting the model aircraft provisions of Public Law 112-95, Sec 336. Modelers operating under the provisions of P.L. 112-95, Sec 336 must comply with the safety guidelines of a nationwide community-based organization.

Myth #4: There are too many commercial UAS operations for the FAA to stop.

Fact—The FAA has to prioritize its safety responsibilities, but the agency is monitoring UAS operations closely. Many times, the FAA learns about suspected commercial UAS operations via a complaint from the public or other businesses. The agency occasionally discovers such operations through the news media or postings on internet sites. When the FAA discovers apparent unauthorized UAS operations, the agency has a number of enforcement tools available to address these operations, including a verbal warning, a warning letter, and an order to stop the operation.

Myth #5: Commercial UAS operations will be OK after September 30, 2015.

Fact—In the 2012 FAA reauthorization legislation, Congress told the FAA to come up with a plan for “safe integration” of UAS by September 30, 2015. Safe integration will be incremental. The agency is still developing regulations, policies and standards that will cover a wide variety of UAS users, and expects to publish a proposed rule for small UAS – under about 55 pounds – later this year. That proposed rule will likely include provisions for commercial operations.

Myth #6: The FAA is lagging behind other countries in approving commercial drones.

Fact – This comparison is flawed. The United States has the busiest, most complex airspace in the world, including many general aviation aircraft that we must consider when planning UAS integration, because those same airplanes and small UAS may occupy the same airspace.

Developing all the rules and standards we need is a very complex task, and we want to make sure we get it right the first time. We want to strike the right balance of requirements for UAS to help foster growth in an emerging industry with a wide range of potential uses, but also keep all airspace users and people on the ground safe.

Myth #7: The FAA predicts as many as 30,000 drones by 2030.

Fact—That figure is outdated. It was an estimate in the FAA’s 2011 Aerospace Forecast. Since then, the agency has refined its prediction to focus on the area of greatest expected growth. The FAA currently estimates as many as 7,500 small commercial UAS may be in use by 2018, assuming the necessary regulations are in place. The number may be updated when the agency publishes the proposed rule on small UAS later this year

(Link: https://www.faa.gov/news/updates/?newsId=76240)

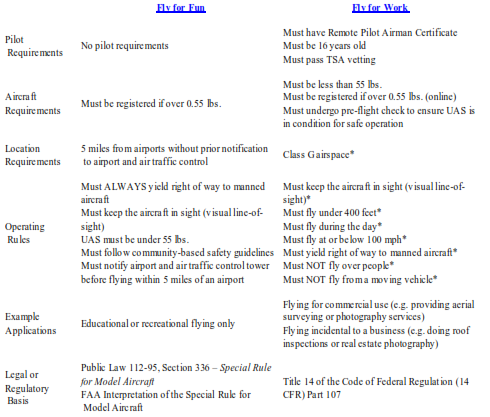

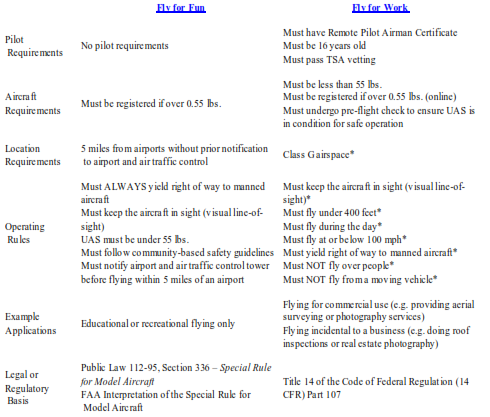

The rules for operating an unmanned aircraft depend on why you want to fly

*These rules are subject to waiver.

(Link: https://www.faa.gov/uas/getting_started/)

The FAA suggests that civilian drone operators should:

SUMMARY OF SMALL UNMANNED AIRCRAFT RULE (PART 107

Operational Limitations

-

Unmanned aircraft must weigh less than 55 lbs. (25 kg).

-

Visual line-of-sight (VLOS) only; the unmanned aircraft must remain within VLOS of the remote pilot in command and the person manipulating the flight controls of the small UAS. Alternatively, the unmanned aircraft must remain within VLOS of the visual observer.

-

At all times the small unmanned aircraft must remain close enough to the remote pilot in command and the person manipulating the flight controls of the small UAS for those people to be capable of seeing the aircraft with vision unaided by any device other than corrective lenses.

-

Small unmanned aircraft may not operate over any persons not directly participating in the operation, not under a covered structure, and not inside a covered stationary vehicle.

-

Daylight-only operations, or civil twilight (30 minutes before official sunrise to 30 minutes after official sunset, local time) with appropriate anti-collision lighting.

-

Must yield right of way to other aircraft.

-

May use visual observer (VO) but not required.

-

First-person view camera cannot satisfy “see-and-avoid” requirement but can be used as long as requirement is satisfied in other ways.

-

Maximum groundspeed of 100 mph (87 knots).

-

Maximum altitude of 400 feet above ground level (AGL) or, if higher than 400 feet AGL, remain within 400 feet of a structure.

-

Minimum weather visibility of 3 miles from control station.

-

Operations in Class B, C, D and E airspace are allowed with the required ATC permission.

-

Operations in Class G airspace are allowed without ATC permission.

-

No person may act as a remote pilot in command or VO for more than one unmanned aircraft operation at one time.

-

No operations from a moving aircraft.

-

No operations from a moving vehicle unless the operation is over a sparsely populated area.

-

No careless or reckless operations.

-

No carriage of hazardous materials.

-

Requires preflight inspection by the remote pilot in command.

-

A person may not operate a small unmanned aircraft if he or she knows or has reason to know of any physical or mental condition that would interfere with the safe operation of a small UAS.

-

Foreign-registered small unmanned aircraft are allowed to operate under part 107 if they satisfy the requirements of part 375.

-

External load operations are allowed if the object being carried by the unmanned aircraft is securely attached and does not adversely affect the flight characteristics or controllability of the aircraft.

-

Transportation of property for compensation or hire allowed provided that- o The aircraft, including its attached systems, payload and cargo weigh less than 55 pounds total;

-

The flight is conducted within visual line of sight and not from a moving vehicle or aircraft; and

-

The flight occurs wholly within the bounds of a State and does not involve transport between (1) Hawaii and another place in Hawaii through airspace outside Hawaii; (2) the District of Columbia and another place in the District of Columbia; or (3) a territory or possession of the United States and another place in the same territory or possession.

-

Most of the restrictions discussed above are waivable if the applicant demonstrates that his or her operation can safely be conducted under the terms of a certificate of waiver.

Remote Pilot in Command Certification and Responsibilities

-

Establishes a remote pilot in command position.

-

A person operating a small UAS must either hold a remote pilot airman certificate with a small UAS rating or be under the direct supervision of a person who does hold a remote pilot certificate (remote pilot in command).

-

To qualify for a remote pilot certificate, a person must:

-

Demonstrate aeronautical knowledge by either:

-

Passing an initial aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center; or

-

Hold a part 61 pilot certificate other than student pilot, complete a flight review within the previous 24 months, and complete a small UAS online training course provided by the FAA.

-

Be vetted by the Transportation Security Administration.

-

Be at least 16 years old.

-

Part 61 pilot certificate holders may obtain a temporary remote pilot certificate immediately upon submission of their application for a permanent certificate. Other applicants will obtain a temporary remote pilot certificate upon successful completion of TSA security vetting. The FAA anticipates that it will be able to issue a temporary remote pilot certificate within 10 business days after receiving a completed remote pilot certificate application.

-

Until international standards are developed, foreign-certificated UAS pilots will be required to obtain an FAA-issued remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating.

A remote pilot in command must:

-

Make available to the FAA, upon request, the small UAS for inspection or testing, and any associated documents/records required to be kept under the rule.

-

Report to the FAA within 10 days of any operation that results in at least serious injury, loss of consciousness, or property damage of at least $500.

-

Conduct a preflight inspection, to include specific aircraft and control station systems checks, to ensure the small UAS is in a condition for safe operation.

-

Ensure that the small unmanned aircraft complies with the existing registration requirements specified in § 91.203(a)(2).

A remote pilot in command may deviate from the requirements of this rule in response to an in-flight emergency.

(Link: https://www.faa.gov/uas/media/Part_107_Summary.pdf)