CHAPTER XII

THE CRICKET

I

THE HOUSEHOLDER

The Field Cricket, the inhabitant of the meadows, is almost as famous as the Cicada, and figures among the limited but glorious number of the classic insects. He owes this honour to his song and his house. One thing alone is lacking to complete his renown. The master of the art of making animals talk, La Fontaine, gives him hardly two lines.

Florian, the other French writer of fables, gives us a story of a Cricket, but it lacks the simplicity of truth and the saving salt of humour. Besides, it represents the Cricket as discontented, bewailing his condition! This is a preposterous idea, for all who have studied him know, on the contrary, that he is very well pleased with his own talent and his own burrow. And indeed, at the end of the story, Florian makes him admit:

“My snug little home is a place of delight;

If you want to live happy, live hidden from sight!”

I find more force and truth in some verses by a friend of mine, of which these are a translation:

Among the beasts a tale is told

How a poor Cricket ventured nigh

His door to catch the sun’s warm gold

And saw a radiant Butterfly.

She passed with tails thrown proudly back

And long gay rows of crescents blue,

Brave yellow stars and bands of black,

The lordliest Fly that ever flew.

“Ah, fly away,” the hermit said,

“Daylong among your flowers to roam;

Nor daisies white nor roses red

Will compensate my lowly home.”

True, all too true! There came a storm

And caught the Fly within its flood,

Staining her broken velvet form

And covering her wings with mud.

The Cricket, sheltered from the rain,

Chirped, and looked on with tranquil eye;

For him the thunder pealed in vain,

The gale and torrent passed him by.

Then shun the world, nor take your fill

Of any of its joys or flowers;

A lowly fireside, calm and still,

At least will grant you tearless hours!1

There I recognise my Cricket. I see him curling his antennæ on the threshold of his burrow, keeping himself cool in front and warm at the back. He is not jealous of the Butterfly; on the contrary, he pities her, with that air of mocking commiseration we often see in those who have houses of their own when they are talking to those who have none. Far from complaining, he is very well satisfied both with his house and his violin. He is a true philosopher: he knows the vanity of things and feels the charm of a modest retreat away from the riot of pleasure-seekers.

Yes, the description is about right, as far as it goes. But the Cricket is still waiting for the few lines needed to bring his merits before the public; and since La Fontaine neglected him, he will have to go on waiting a long time.

To me, as a naturalist, the important point in the two fables is the burrow on which the moral is founded. Florian speaks of the snug retreat; the other praises his lowly home. It is the dwelling, therefore, that above all compels attention, even that of the poet, who as a rule cares little for realities.

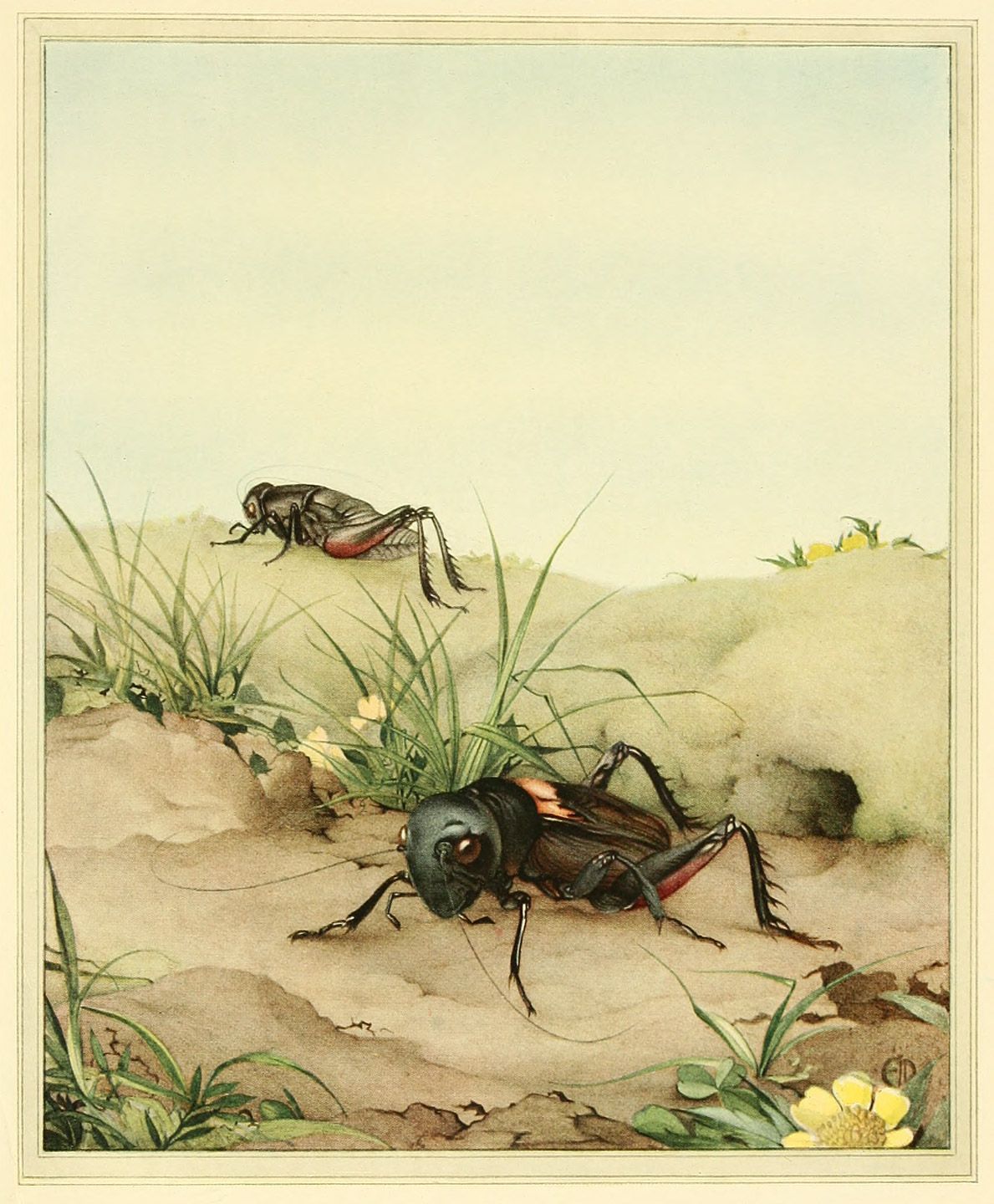

In this matter, indeed, the Cricket is extraordinary. Of all our insects he is the only one who, when full-grown, possesses a fixed home, the reward of his own industry. During the bad season of the year, most of the others burrow or skulk in some temporary refuge, a refuge obtained free of cost and abandoned without regret. Several of them create marvels with a view to settling their family: cotton satchels, baskets made of leaves, towers of cement. Some live permanently in ambush, lying in wait for their prey. The Tiger-beetle, for instance, digs himself a perpendicular hole, which he stops up with his flat, bronze head. If any other insect steps on this deceptive trap-door it immediately tips up, and the unhappy wayfarer disappears into the gulf. The Ant-lion makes a slanting funnel in the sand. Its victim, the Ant, slides down the slant and is then stoned, from the bottom of the funnel, by the hunter, who turns his neck into a catapult. But these are all temporary refuges or traps.

The laboriously constructed home, in which the insect settles down with no intention of moving, either in the happy spring or in the woeful winter season; the real manor-house, built for peace and comfort, and not as a hunting-box or a nursery—this is known to the Cricket alone. On some sunny, grassy slope he is the owner of a hermitage. While all the others lead vagabond lives, sleeping in the open air or under the casual shelter of a dead leaf or a stone, or the pealing bark of an old tree, he is a privileged person with a permanent address.

The making of a home is a serious problem. It has been solved by the Cricket, by the Rabbit, and lastly by man. In my neighbourhood the Fox and the Badger have holes, which are largely formed by the irregularities of the rock. A few repairs, and the dug-out is completed. The Rabbit is cleverer than these, for he builds his house by burrowing wherever he pleases, when there is no natural passage that allows him to settle down free of all trouble.

The Cricket is cleverer than any of them. He scorns chance refuges, and always chooses the site of his home carefully, in well-drained ground, with a pleasant sunny aspect. He refuses to make use of ready-made caves that are inconvenient and rough: he digs every bit of his villa, from the entrance-hall to the back-room.

I see no one above him, in the art of house-building, except man; and even man, before mixing mortar to hold stones together, or kneading clay to coat his hut of branches, fought with wild beasts for a refuge in the rocks. Why is it that a special instinct is bestowed on one particular creature? Here is one of the humblest of creatures able to lodge himself to perfection. He has a home, an advantage unknown to many civilised beings; he has a peaceful retreat, the first condition of comfort; and no one around him is capable of settling down. He has no rivals but ourselves.

Whence does he derive this gift? Is he favoured with special tools? No, the Cricket is not an expert in the art of digging; in fact, one is rather surprised at the result when one considers the feebleness of his means.

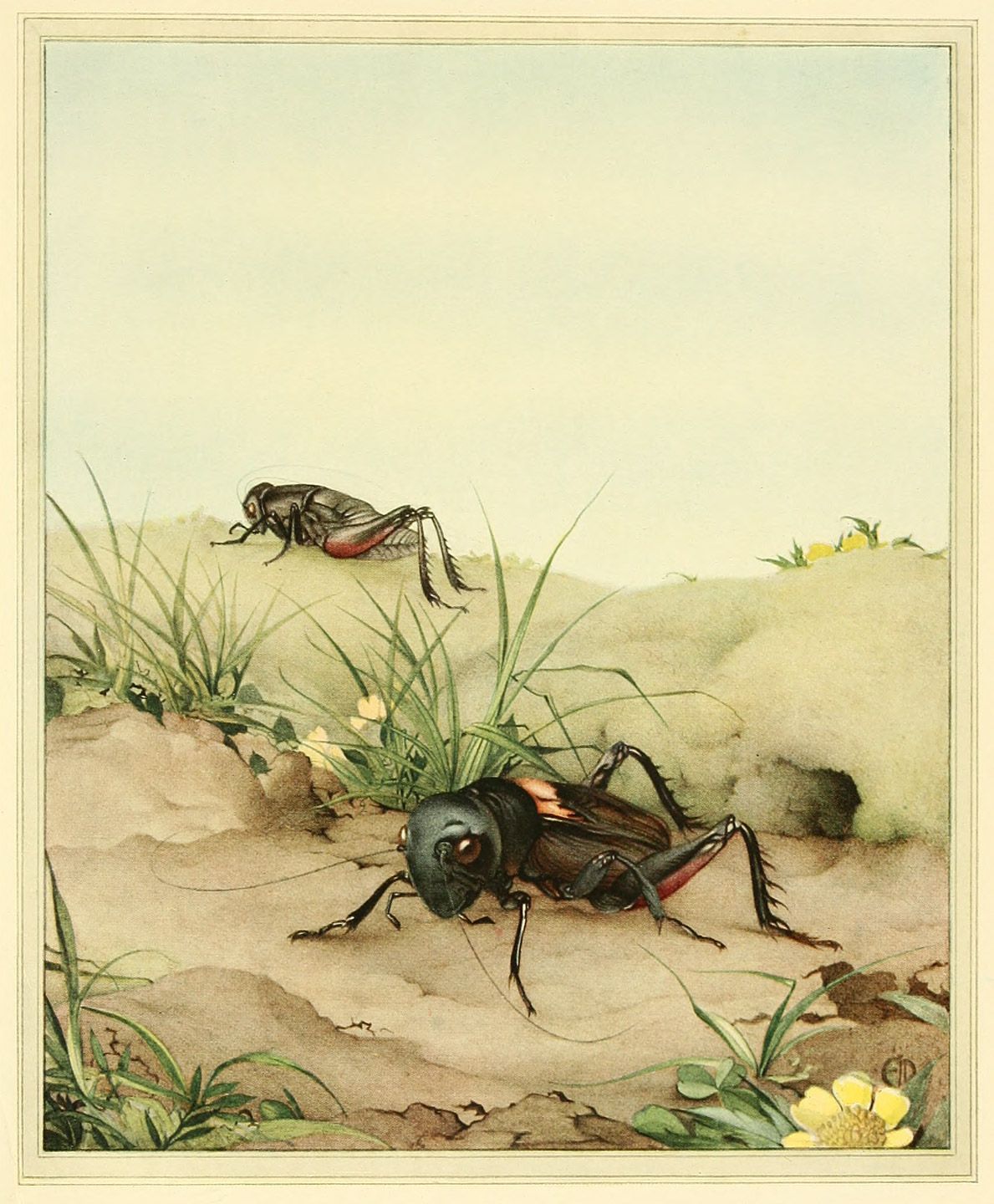

THE FIELD CRICKET

Here is one of the humblest of creatures able to lodge himself to perfection. He has a home; he has a peaceful retreat, the first condition of comfort

Is a home a necessity to him, on account of an exceptionally delicate skin? No, his near kinsmen have skins as sensitive as his, yet do not dread the open air at all.

Is the house-building talent the result of his anatomy? Has he any special organ that suggests it? No: in my neighbourhood there are three other Crickets who are so much like the Field Cricket in appearance, colour, and structure, that at the first glance one would take them for him. Of these faithful copies, not one knows how to dig himself a burrow. The Double-spotted Cricket inhabits the heaps of grass that are left to rot in damp places; the Solitary Cricket roams about the dry clods turned up by the gardener’s spade; the Bordeaux Cricket is not afraid to make his way into our houses, where he sings discreetly, during August and September, in some cool, dark spot.

There is no object in continuing these questions: the answer would always be No. Instinct never tells us its causes. It depends so little on an insect’s stock of tools that no detail of anatomy, nothing in the creature’s formation, can explain it to us or make us foresee it. These four similar Crickets, of whom only one can burrow, are enough to show us our ignorance of the origin of instinct.

Who does not know the Cricket’s house? Who has not, as a child playing in the fields, stopped in front of the hermit’s cabin? However light your footfall, he has heard you coming, and has abruptly withdrawn to the very bottom of his hiding-place. When you arrive, the threshold of the house is deserted.

Every one knows the way to bring out the skulker. You insert a straw and move it gently about the burrow. Surprised at what is happening above, the tickled and teased Cricket ascends from his back room; he stops in the passage, hesitates, and waves his delicate antennæ inquiringly. He comes to the light, and, once outside, he is easy to catch, since these events have puzzled his poor head. Should he be missed at the first attempt he may become suspicious and refuse to appear. In that case he can be flooded out with a glass of water.

Those were adorable times when we were children, and hunted Crickets along the grassy paths, and put them in cages, and fed them on a leaf of lettuce. They all come back to me to-day, those times, as I search the burrows for subjects to study. They seem like yesterday when my companion, little Paul, an expert in the use of the straw, springs up suddenly after a long trial of skill and patience, and cries excitedly: “I’ve got him! I’ve got him!”

Quick, here’s a bag! In you go, my little Cricket! You shall be petted and pampered, but you must teach us something, and first of all you must show us your house.

II

HIS HOUSE

It is a slanting gallery in the grass, on some sunny bank which soon dries after a shower. It is nine inches long at most, hardly as thick as one’s finger, and straight or bent according to the nature of the ground. As a rule, a tuft of grass half conceals the home, serving as a porch and throwing the entrance discreetly into shadow. When the Cricket goes out to browse upon the surrounding turf he does not touch this tuft. The gently sloping threshold, carefully raked and swept, extends for some distance; and this is the terrace on which, when everything is peaceful round about, the Cricket sits and scrapes his fiddle.

The inside of the house is devoid of luxury, with bare and yet not coarse walls. The inhabitant has plenty of leisure to do away with any unpleasant roughness. At the end of the passage is the bedroom, a little more carefully smoothed than the rest, and slightly wider. All said, it is a very simple abode, exceedingly clean, free from damp, and conforming to the rules of hygiene. On the other hand, it is an enormous undertaking, a gigantic tunnel, when we consider the modest tools with which the Cricket has to dig. If we wish to know how he does it, and when he sets to work, we must go back to the time when the egg is laid.

The Cricket lays her eggs singly in the soil, like the Decticus, at a depth of three-quarters of an inch. She arranges them in groups, and lays altogether about five or six hundred. The egg is a little marvel of mechanism. After the hatching it appears as an opaque white cylinder, with a round and very regular hole at the top. To the edge of this hole is fastened a cap, like a lid. Instead of bursting open anyhow under the thrusts of the larva within, it opens of its own accord along a circular line—a specially prepared line of least resistance.

About a fortnight after the egg is laid, two large, round, rusty-black dots darken the front end. A little way above these two dots, right at the top of the cylinder, you see the outline of a thin circular swelling. This is the line where the shell is preparing to break open. Soon the transparency of the egg allows one to see the delicate markings of the tiny creature’s segments. Now is the time to be on the watch, especially in the morning.

Fortune loves the persevering, and if we pay constant visits to the eggs we shall be rewarded. All round the swelling, where the resistance of the shell has gradually been overcome, the end of the egg becomes detached. Being pushed back by the forehead of the little creature within, it rises and falls to one side like the top of a tiny scent-bottle. The Cricket pops out like a Jack-in-the-box.

When he is gone the shell remains distended, smooth, intact, pure white, with the cap or lid hanging from the opening. A bird’s egg breaks clumsily under the blows of a wart that grows for the purpose at the end of the Chick’s beak; the Cricket’s egg is more ingeniously made, and opens like an ivory case. The thrust of the creature’s head is enough to work the hinge.

I said above that, when the lid is lifted, a young Cricket pops out; but this is not quite accurate. What appears is the swaddled grub, as yet unrecognisable in a tight-fitting sheath. The Decticus, you will remember, who is hatched in the same way under the soil, wears a protective covering during his journey to the surface. The Cricket is related to the Decticus, and therefore wears the same livery, although in point of fact he does not need it. The egg of the Decticus remains underground for eight months, so the poor grub has to fight its way through soil that has grown hard, and it therefore needs a covering for its long shanks. But the Cricket is shorter and stouter, and since its egg is only in the ground for a few days it has nothing worse than a powdery layer of earth to pass through. For these reasons it requires no overall, and leaves it behind in the shell.

As soon as he is rid of his swaddling-clothes the young Cricket, pale all over, almost white, begins to battle with the soil overhead. He hits out with his mandibles; he sweeps aside and kicks behind him the powdery earth, which offers no resistance. Very soon he is on the surface, amidst the joys of the sunlight and the perils of conflict with his fellow-creatures—poor feeble mite that he is, hardly larger than a Flea.

By the end of twenty-four hours he has turned into a magnificent blackamoor, whose ebon hue vies with that of the full-grown insect. All that remains of his original pallor is a white sash that girds his chest. Very nimble and alert, he sounds the surrounding air with his long, quivering antennæ, and runs and jumps about with great impetuosity. Some day he will be too fat to indulge in such antics.

And now we see why the mother Cricket lays so many eggs. It is because most of the young ones are doomed to death. They are massacred in huge numbers by other insects, and especially by the little Grey Lizard and the Ant. The latter, loathsome freebooter that she is, hardly leaves me a Cricket in my garden. She snaps up the poor little creatures and gobbles them down at frantic speed.

Oh, the execrable wretch! And to think that we place the Ant in the front rank of insects! Books are written in her honour, and the stream of praise never runs dry. The naturalists hold her in great esteem; and add daily to her fame. It would seem that with animals, as with men, the surest way to attract attention is to do harm to others.

Nobody asks about the Beetles who do such valuable work as scavengers, whereas everybody knows the Gnat, that drinker of men’s blood; the Wasp, that hot-tempered swashbuckler, with her poisoned dagger; and the Ant, that notorious evil-doer who, in our southern villages, saps and imperils the rafters of a dwelling as cheerfully as she eats a fig.

The Ant massacres the Crickets in my garden so thoroughly that I am driven to look for them outside the enclosure. In August, among the fallen leaves, where the grass has not been wholly scorched by the sun, I find the young Cricket, already rather big, and now black all over, with not a vestige of his white girdle remaining. At this period of his life he is a vagabond: the shelter of a dead leaf or a flat stone is enough for him.

Many of those who survived the raids of the Ants now fall victims to the Wasp, who hunts down the wanderers and stores them underground. If they would but dig their dwellings a few weeks before the usual time they would be saved; but they never think of it. They are faithful to their ancient customs.

It is at the close of October, when the first cold weather threatens, that the burrow is taken in hand. The work is very simple, if I may judge by my observation of the caged insect. The digging is never done at a bare point in the pan, but always under the shelter of some withered lettuce-leaf, a remnant of the food provided. This takes the place of the grass tuft that seems indispensable to the secrecy of the home.

The miner scrapes with his fore-legs, and uses the pincers of his mandibles to pull out the larger bits of gravel. I see him stamping with his powerful hind-legs, furnished with a double row of spikes; I see him raking the rubbish, sweeping it backwards and spreading it slantwise. There you have the whole process.

The work proceeds pretty quickly at first. In the yielding soil of my cages the digger disappears underground after a spell that lasts a couple of hours. He returns to the entrance at intervals, always backwards and always sweeping. Should he be overcome with fatigue he takes a rest on the threshold of his half-finished home, with his head outside and his antennæ waving feebly. He goes in again, and resumes work with pincers and rakes. Soon the periods of rest become longer, and wear out my patience.

The most urgent part of the work is done. Once the hole is a couple of inches deep, it suffices for the needs of the moment. The rest will be a long affair, carried out in a leisurely way, a little one day and a little the next: the hole will be made deeper and wider as the weather grows colder and the insect larger. Even in winter, if the temperature be mild and the sun shining on the entrance to the dwelling, it is not unusual to see the Cricket shooting out rubbish. Amid the joys of spring the upkeep of the building still continues. It is constantly undergoing improvements and repairs until the owner’s death.

When April ends the Cricket’s song begins; at first in rare and shy solos, but soon in a general symphony in which each clod of turf boasts its performer. I am more than inclined to place the Cricket at the head of the spring choristers. In our waste-lands, when the thyme and lavender are gaily flowering, the Crested Lark rises like a lyrical rocket, his throat swelling with notes, and from the sky sheds his sweet music upon the fallows. Down below the Crickets chant the responses. Their song is monotonous and artless, but well suited in its very lack of art to the simple gladness of reviving life. It is the hosanna of the awakening, the sacred alleluia understood by swelling seed and sprouting blade. In this duet I should award the palm to the Cricket. His numbers and his unceasing note deserve it. Were the Lark to fall silent, the fields blue-grey with lavender, swinging its fragrant censors before the sun, would still receive from this humble chorister a solemn hymn of praise.

III

HIS MUSICAL-BOX

In steps Science, and says to the Cricket bluntly:

“Show us your musical-box.”

Like all things of real value, it is very simple. It is based on the same principle as that of the Grasshoppers: a bow with a hook to it, and a vibrating membrane. The right wing-case overlaps the left and covers it almost completely, except where it folds back sharply and encases the insect’s side. It is the opposite arrangement to that which we find in the Green Grasshopper, the Decticus, and their kinsmen. The Cricket is right-handed, the others left-handed.

The two wing-cases are made in exactly the same way. To know one is to know the other. They lie flat on the insect’s back, and slant suddenly at the side in a right-angled fold, encircling the body with a delicately veined pinion.

If you hold one of these wing-cases up to the light you will see that is it a very pale red, save for two large adjoining spaces; a larger, triangular one in front, and a smaller, oval one at the back. They are crossed by faint wrinkles. These two spaces are the sounding-boards, or drums. The skin is finer here than elsewhere, and transparent, though of a somewhat smoky tint.

At the hinder edge of the front part are two curved, parallel veins, with a cavity between them. This cavity contains five or six little black wrinkles that look like the rungs of a tiny ladder. They supply friction: they intensify the vibration by increasing the number of points touched by the bow.

On the lower surface one of the two veins that surround the cavity of the rungs becomes a rib cut into the shape of a hook. This is the bow. It is provided with about a hundred and fifty triangular teeth of exquisite geometrical regularity.

It is a fine instrument indeed. The hundred and fifty teeth of the bow, biting into the rungs of the opposite wing-case, set the four drums in motion at one and the same time, the lower pair by direct friction, the upper pair by the shaking of the friction-apparatus. What a rush of sound! The Cricket with his four drums throws his music to a distance of some hundreds of yards.

He vies with the Cicada in shrillness, without having the latter’s disagreeable harshness. And better still: this favoured creature knows how to modulate his song. The wing-cases, as I said, extend over each side in a wide fold. These are the dampers which, lowered to a greater or less depth, alter the intensity of the sound. According to the extent of their contact with the soft body of the Cricket they allow him to sing gently at one time and fortissimo at another.

The exact similarity of the two wing-cases is worthy of attention. I can see clearly the function of the upper bow, and the four sounding-spaces which sets it in motion; but what is the good of the lower one, the bow on the left wing? Not resting on anything, it has nothing to strike with its hook, which is as carefully toothed as the other. It is absolutely useless, unless the apparatus can invert the order of its two parts, and place that above which is below. If that could be done, the perfect symmetry of the instrument is such that the mechanism would be the same as before, and the insect would be able to play with the bow that is at present useless. The lower fiddlestick would become the upper, and the tune would be the same.

I suspected at first that the Cricket could use both bows, or at least that there were some who were permanently left-handed. But observation has convinced me of the contrary. All the Crickets I have examined—and they are many—without a single exception carried the right wing-case above the left.

I even tried to bring about by artificial means what Nature refused to show me. Using my forceps, very gently of course, and without straining the wing-cases, I made these overlap the opposite way. It is easily done with a little skill and patience. Everything went well: there was no dislocation of the shoulders, the membranes were not creased.

I almost expected the Cricket to sing, but I was soon undeceived. He submitted for a few moments; but then, finding himself uncomfortable, he made an effort and restored his instrument to its usual position. In vain I repeated the operation: the Cricket’s obstinacy triumphed over mine.

Then I thought I would make the attempt while the wing-cases were quite new and plastic, at the moment when the larva casts its skin. I secured one at the point of being transformed. At this stage the future wings and wing-cases form four tiny flaps, which, by their shape and scantiness, and by the way they stick out in different directions, remind me of the short jackets worn by the Auvergne cheesemakers. The larva cast off these garments before my eyes.

The wing-cases developed bit by bit, and opened out. There was no sign to tell me which would overlap the other. Then the edges touched: a few moments longer and the right would be over the left. This was the time to intervene.

With a straw I gently changed the position, bringing the left edge over the right. In spite of some protest from the insect I was quite successful: the left wing-case pushed forward, though only very little. Then I left it alone, and gradually the wing-cases matured in the inverted position. The Cricket was left-handed. I expected soon to see him wield the fiddlestick which the members of his family never employ.

On the third day he made a start. A few brief grating sounds were heard—the noise of a machine out of gear shifting its parts back into their proper order. Then the tune began, with its accustomed tone and rhythm.

Alas, I had been over-confident in my mischievous straw! I thought I had created a new type of instrumentalist, and I had obtained nothing at all! The Cricket was scraping with his right fiddlestick, and always would. With a painful effort he had dislocated his shoulders, which I had forced to harden in the wrong way. He had put back on top that which ought to be on top, and underneath that which ought to be underneath. My sorry science tried to make a left-handed player of him. He laughed at my devices, and settled down to be right-handed for the rest of his life.

Enough of the instrument; let us listen to the music. The Cricket sings on the threshold of his house, in the cheerful sunshine, never indoors. The wing-cases utter their cri-cri in a soft tremolo. It is full, sonorous, nicely cadenced, and lasts indefinitely. Thus are the leisures of solitude beguiled all through the spring. The hermit at first sings for his own pleasure. Glad to be alive, he chants the praises of the sun that shines upon him, the grass that feeds him, the peaceful retreat that harbours him. The first object of his bow is to hymn the pleasures of life.

Later on he plays to his mate. But, to tell the truth, his attention is rewarded with little gratitude; for in the end she quarrels with him ferociously, and unless he takes to flight she cripples him—and even eats him more or less. But indeed, in any case he soon dies. Even if he escapes his pugnacious mate, he perishes in June. We are told that the music-loving Greeks used to keep Cicadæ in cages, the better to enjoy their singing. I venture to disbelieve the story. In the first place the harsh clicking of the Cicadæ, when long continued at close quarters, is a torture to ears that are at all delicate. The Greeks’ sense of hearing was too well trained to take pleasure in such raucous sounds away from the general concert of the fields, which is heard at a distance.

In the second place it is absolutely impossible to bring up Cicadæ in captivity, unless we cover over a whole olive-tree or plane-tree. A single day spent in a cramped enclosure would make the high-flying insect die of boredom.

Is it not possible that people have confused the Cricket with the Cicada, as they also do the Green Grasshopper? With the Cricket they would be quite right. He is one who bears captivity gaily: his stay-at-home ways predispose him to it. He lives happily and whirrs without ceasing in a cage no larger than a man’s fist, provided that he has his lettuce-leaf every day. Was it not he whom the small boys of Athens reared in little wire cages hanging on a window-frame?

The small boys of Provence, and all the South, have the same tastes. In the towns a Cricket becomes the child’s treasured possession. The insect, petted and pampered, sings to him of the simple joys of the country. Its death throws the whole household into a sort of mourning.

The three other Crickets of my neighbourhood all carry the same musical instrument as the Field Cricket, with slight variation of detail. Their song is much alike in all cases, allowing for differences of size. The smallest of the family, the Bordeaux Cricket, sometimes ventures into the dark corners of my kitchen, but his song is so faint that it takes a very attentive ear to hear it.

The Field Cricket sings during the sunniest hours of the spring: during the still summer nights we have the Italian Cricket. He is a slender, feeble insect, quite pale, almost white, as beseems his nocturnal habits. You are afraid of crushing him, if you so much as take him in your fingers. He lives high in air, on shrubs of every kind, or on the taller grasses; and he rarely descends to earth. His song, the sweet music of the still, hot evenings from July to October; begins at sunset and continues for the best part of the night.

This song is known to everybody here in Provence, for the smallest clump of bushes has its orchestra. The soft, slow gri-i-i gri-i-i is made more expressive by a slight tremolo. If nothing happens to disturb the insect the sound remains unaltered; but at the least noise the musician becomes a ventriloquist. You hear him quite close, in front of you; and then, all of a sudden, you hear him fifteen yards away. You move towards the sound. It is not there: it comes from the original place. No, it doesn’t after all. Is it over there on the left, or does it come from behind? One is absolutely at a loss, quite unable to find the spot where the music is chirping.

This illusion of varying distance is produced in two ways. The sounds become loud or soft, open or muffled, according to the exact part of the lower wing-case that is pressed by the bow. And they are also modified by the position of the wing-cases. For the loud sounds these are raised to their full height: for the muffled sounds they are lowered more or less. The pale Cricket misleads those who hunt for him by pressing the edges of his vibrating flaps against his soft body.

I know no prettier or more limpid insect-song than his, heard in the deep stillness of an August evening. How often have I lain down on the ground among the rosemary bushes of my harmas, to listen to the delightful concert!

The Italian Cricket swarms in my enclosure. Every tuft of red-flowering rock-rose has its chorister; so has every clump of lavender. The bushy arbutus-shrubs, the turpentine-trees, all become orchestras. And in its clear voice, so full of charm, the whole of this little world, from every shrub and every branch, sings of the gladness of life.

High up above my head the Swan stretches its great cross along the Milky Way: below, al