CHAPTER IV

THE PRAYING MANTIS

I

HER HUNTING

There is an insect of the south that is quite as interesting as the Cicada, but much less famous, because it makes no noise. Had it been provided with cymbals, its renown would have been greater than the celebrated musician’s, for it is most unusual both in shape and habits.

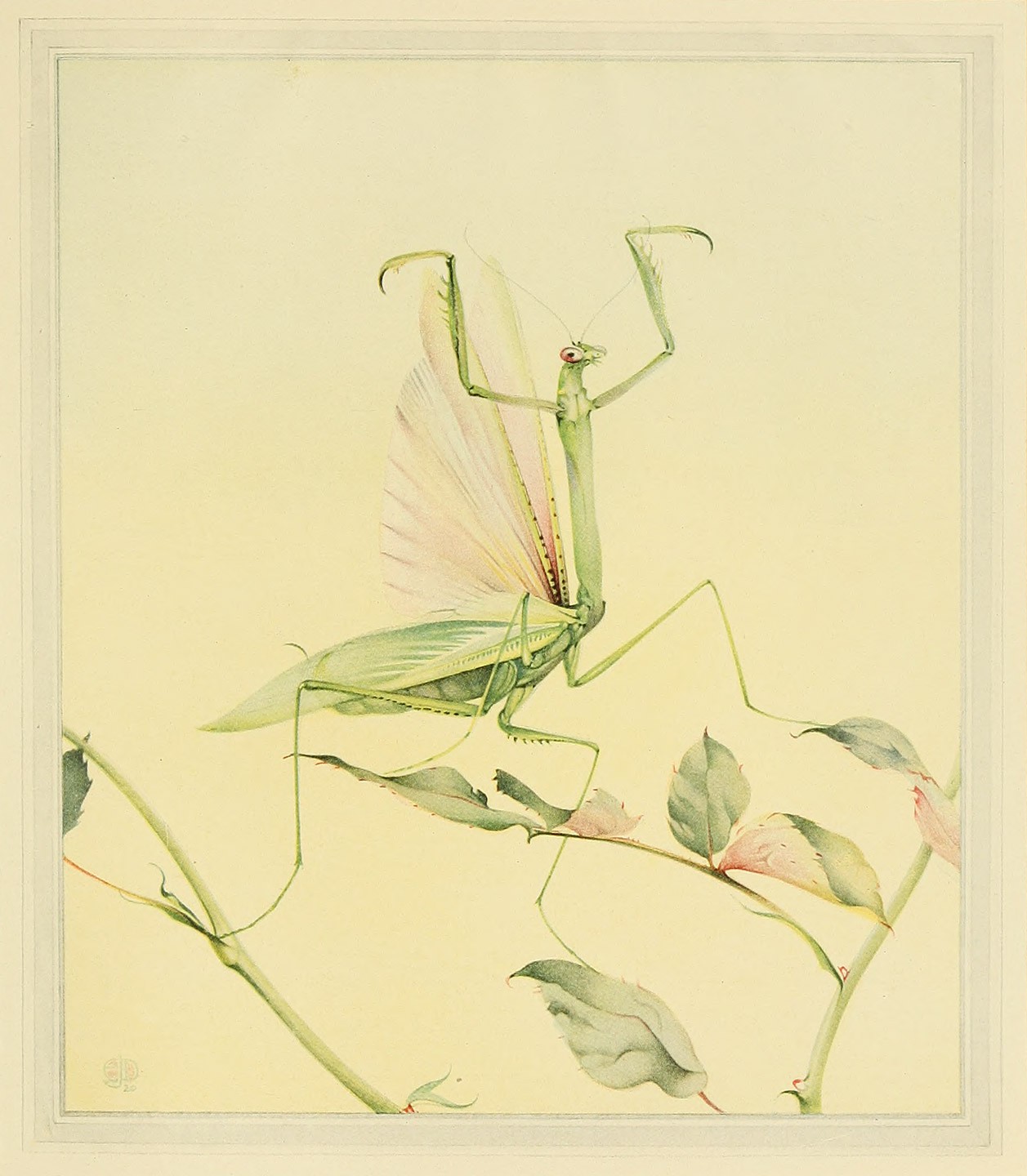

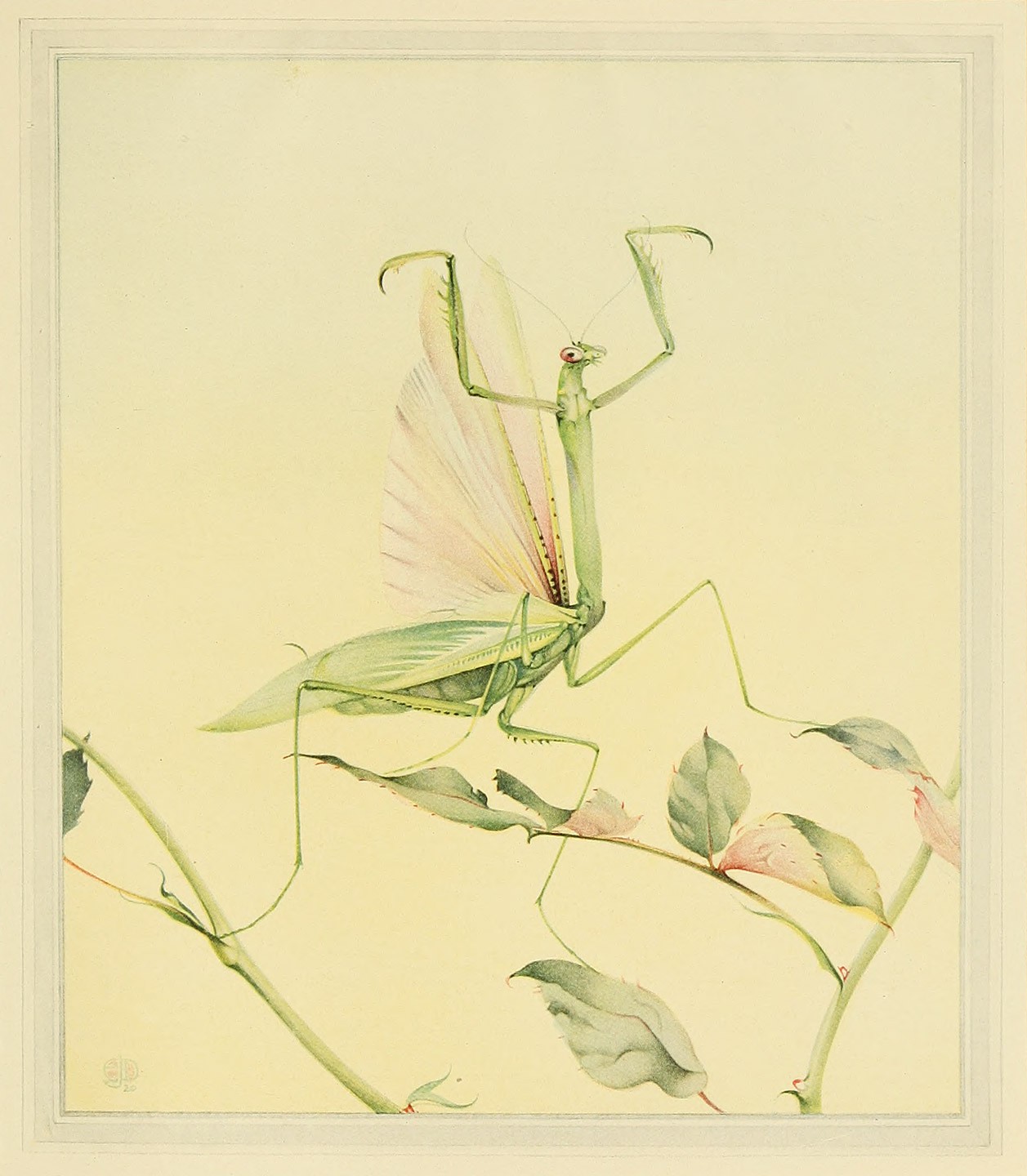

A long time ago, in the days of ancient Greece, this insect was named Mantis, or the Prophet. The peasant saw her on the sun-scorched grass, standing half-erect in a very imposing and majestic manner, with her broad green gossamer wings trailing like long veils, and her fore-legs, like arms, raised to the sky as though in prayer. To the peasant’s ignorance the insect seemed like a priestess or a nun, and so she came to be called the Praying Mantis.

There was never a greater mistake! Those pious airs are a fraud; those arms raised in prayer are really the most horrible weapons, which slay whatever passes within reach. The Mantis is fierce as a tigress, cruel as an ogress. She feeds only on living creatures.

There is nothing in her appearance to inspire dread. She is not without a certain beauty, with her slender, graceful figure, her pale-green colouring, and her long gauze wings. Having a flexible neck, she can move her head freely in all directions. She is the only insect that can direct her gaze wherever she will. She almost has a face.

Great is the contrast between this peaceful-looking body and the murderous machinery of the fore-legs. The haunch is very long and powerful, while the thigh is even longer, and carries on its lower surface two rows of sharp spikes or teeth. Behind these teeth are three spurs. In short, the thigh is a saw with two blades, between which the leg lies when folded back.

This leg itself is also a double-edged saw, provided with a greater number of teeth than the thigh. It ends in a strong hook with a point as sharp as a needle, and a double blade like a curved pruning-knife. I have many painful memories of this hook. Many a time, when Mantis-hunting, I have been clawed by the insect and forced to ask somebody else to release me. No insect in this part of the world is so troublesome to handle. The Mantis claws you with her pruning-hooks, pricks you with her spikes, seizes you in her vice, and makes self-defence impossible if you wish to keep your captive alive.

THE PRAYING MANTIS

A long time ago, in the days of ancient Greece, this insect was named Mantis, or the Prophet

When at rest, the trap is folded back against the chest and looks quite harmless. There you have the insect praying. But if a victim passes by, the appearance of prayer is quickly dropped. The three long divisions of the trap are suddenly unfolded, and the prey is caught with the sharp hook at the end of them, and drawn back between the two saws. Then the vice closes, and all is over. Locusts, Grasshoppers, and even stronger insects are helpless against the four rows of teeth.

It is impossible to make a complete study of the habits of the Mantis in the open fields, so I am obliged to take her indoors. She can live quite happily in a pan filled with sand and covered with a gauze dish-cover, if only she be supplied with plenty of fresh food. In order to find out what can be done by the strength and daring of the Mantis, I provide her not only with Locusts and Grasshoppers, but also with the largest Spiders of the neighbourhood. This is what I see.

A grey Locust, heedless of danger, walks towards the Mantis. The latter gives a convulsive shiver, and suddenly, in the most surprising way, strikes an attitude that fills the Locust with terror, and is quite enough to startle any one. You see before you unexpectedly a sort of bogy-man or Jack-in-the-box. The wing-covers open; the wings spread to their full extent and stand erect like sails, towering over the insect’s back; the tip of the body curls up like a crook, rising and falling with short jerks, and making a sound like the puffing of a startled Adder. Planted defiantly on its four hind-legs, the Mantis holds the front part of its body almost upright. The murderous legs open wide, and show a pattern of black-and-white spots beneath them.

In this strange attitude the Mantis stands motionless, with eyes fixed on her prey. If the Locust moves, the Mantis turns her head. The object of this performance is plain. It is intended to strike terror into the heart of the victim, to paralyse it with fright before attacking it. The Mantis is pretending to be a ghost!

The plan is quite successful. The Locust sees a spectre before him, and gazes at it without moving. He to whom leaping is so easy makes no attempt at escape. He stays stupidly where he is, or even draws nearer with a leisurely step.

As soon as he is within reach of the Mantis she strikes with her claws; her double saws close and clutch; the poor wretch protests in vain; the cruel ogress begins her meal.

The pretty Crab Spider stabs her victim in the neck, in order to poison it and make it helpless. In the same way the Mantis attacks the Locust first at the back of the neck, to destroy its power of movement. This enables her to kill and eat an insect as big as herself, or even bigger. It is amazing that the greedy creature can contain so much food.

The various Digger-wasps receive visits from her pretty frequently. Posted near the burrows on a bramble, she waits for chance to bring near her a double prize, the Hunting-wasp and the prey she is bringing home. For a long time she waits in vain; for the Wasp is suspicious and on her guard: still, now and then a rash one is caught. With a sudden rustle of wings the Mantis terrifies the new-comer, who hesitates for a moment in her fright. Then, with the sharpness of a spring, the Wasp is fixed as in a trap between the blades of the double saw—the toothed fore-arm and toothed upper-arm of the Mantis. The victim is then gnawed in small mouthfuls.

I once saw a Bee-eating Wasp, while carrying a Bee to her storehouse, attacked and caught by a Mantis. The Wasp was in the act of eating the honey she had found in the Bee’s crop. The double saw of the Mantis closed suddenly on the feasting Wasp; but neither terror nor torture could persuade that greedy creature to leave off eating. Even while she was herself being actually devoured she continued to lick the honey from her Bee!

I regret to say that the meals of this savage ogress are not confined to other kinds of insects. For all her sanctimonious airs she is a cannibal. She will eat her sister as calmly as though she were a Grasshopper; and those around her will make no protest, being quite ready to do the same on the first opportunity. Indeed, she even makes a habit of devouring her mate, whom she seizes by the neck and then swallows by little mouthfuls, leaving only the wings.

She is worse than the Wolf; for it is said that even Wolves never eat each other.

II

HER NEST

After all, however, the Mantis has her good points, like most people. She makes a most marvellous nest.

This nest is to be found more or less everywhere in sunny places: on stones, wood, vine-stocks, twigs, or dry grass, and even on such things as bits of brick, strips of linen, or the shrivelled leather of an old boot. Any support will serve, as long as there is an uneven surface to form a solid foundation.

In size the nest is between one and two inches long, and less than an inch wide; and its colour is as golden as a grain of wheat. It is made of a frothy substance, which has become solid and hard, and it smells like silk when it is burnt. The shape of it varies according to the support on which it is based, but in all cases the upper surface is convex. One can distinguish three bands, or zones, of which the middle one is made of little plates or scales, arranged in pairs and overlapping like the tiles of a roof. The edges of these plates are free, forming two rows of slits or little doorways, through which the young Mantis escapes at the moment of hatching. In every other part the wall of the nest is impenetrable.

The eggs are arranged in layers, with the ends containing the heads pointed towards the doorways. Of these doorways, as I have just said, there are two rows. One half of the grubs will go out through the right door, and the other half through the left.

It is a remarkable fact that the mother Mantis builds this cleverly-made nest while she is actually laying her eggs. From her body she produces a sticky substance, rather like the Caterpillar’s silk-fluid; and this material she mixes with the air and whips into froth. She beats it into foam with two ladles that she has at the tip of her body, just as we beat white of egg with a fork. The foam is greyish-white, almost like soapsuds, and when it first appears it is sticky; but two minutes afterwards it has solidified.

In this sea of foam the Mantis deposits her eggs. As each layer of eggs is laid, it is covered with froth, which quickly becomes solid.

In a new nest the belt of exit-doors is coated with a material that seems different from the rest—a layer of fine porous matter, of a pure, dull, almost chalky white, which contrasts with the dirty white of the remainder of the nest. It is like the mixture that confectioners make of whipped white of egg, sugar, and starch, with which to ornament their cakes. This snowy covering is very easily crumbled and removed. When it is gone the exit-belt is clearly visible, with its two rows of plates. The wind and rain sooner or later remove it in strips or flakes, and therefore the old nests show no traces of it.

But these two materials, though they appear different, are really only two forms of the same matter. The Mantis with her ladles sweeps the surface of the foam, skimming the top of the froth, and collecting it into a band along the back of the nest. The ribbon that looks like sugar-icing is merely the thinnest and lightest portion of the sticky spray, which appears whiter than the nest because its bubbles are more delicate, and reflect more light.

It is truly a wonderful piece of machinery that can, so methodically and swiftly, produce the horny central substance on which the first eggs are laid, the eggs themselves, the protecting froth, the soft sugar-like covering of the doorways, and at the same time can build overlapping plates, and the narrow passages leading to them! Yet the Mantis, while she is doing all this, hangs motionless on the foundation of the nest. She gives not a glance at the building that is rising behind her. Her legs act no part in the affair. The machinery works by itself.

As soon as she has done her work the mother withdraws. I expected to see her return and show some tender feeling for the cradle of her family, but it evidently has no further interest for her.

The Mantis, I fear, has no heart. She eats her husband, and deserts her children.

III

THE HATCHING OF HER EGGS

The eggs of the Mantis usually hatch in bright sunshine, at about ten o’clock on a mid-June morning.

As I have already told you, there is only one part of the nest from which the grub can find an outlet, namely the band of scales round the middle. From under each of these scales one sees slowly appearing a blunt, transparent lump, followed by two large black specks, which are the creature’s eyes. The baby grub slips gently under the thin plate and half releases itself. It is reddish yellow, and has a thick, swollen head. Under its outer skin it is quite easy to distinguish the large black eyes, the mouth flattened against the chest, the legs plastered to the body from front to back. With the exception of these legs the whole thing reminds one somewhat of the first state of the Cicada on leaving the egg.

Like the Cicada, the young Mantis finds it necessary to wear an overall when it is coming into the world, for the sake of convenience and safety. It has to emerge from the depths of the nest through narrow, winding ways, in which full-spread slender limbs could not find enough room. The tall stilts, the murderous harpoons, the delicate antennæ, would hinder its passage, and indeed make it impossible. The creature therefore appears in swaddling-clothes, and has the shape of a boat.

When the grub peeps out under the thin scales of its nest its head becomes bigger and bigger, till it looks like a throbbing blister. The little creature alternately pushes forward and draws back, in its efforts to free itself, and at each movement the head grows larger. At last the outer skin bursts at the upper part of the chest, and the grub wriggles and tugs and bends about, determined to throw off its overall. Finally the legs and the long antennæ are freed, and a few shakes complete the operation.

It is a striking sight to see a hundred young Mantes coming from the nest at once. Hardly does one tiny creature show its black eyes under a scale before a swarm of others appears. It is as though a signal passed from one to the other, so swiftly does the hatching spread. Almost in a moment the middle zone of the nest is covered with grubs, who run about feverishly, stripping themselves of their torn garments. Then they drop off, or clamber into the nearest foliage. A few days later a fresh swarm appears, and so on till all the eggs are hatched.

But alas! the poor grubs are hatched into a world of dangers. I have seen them hatching many times, both out of doors in my enclosure, and in the seclusion of a greenhouse, where I hoped I should be better able to protect them. Twenty times at least I have watched the scene, and every time the slaughter of the grubs has been terrible. The Mantis lays many eggs, but she will never lay enough to cope with the hungry murderers who lie in wait until the grubs appear.

The Ants, above all, are their enemies. Every day I find them visiting my nests. It is in vain for me to interfere; they always get the better of me. They seldom succeed in entering the nest; its hard walls form too strong a fortress. But they wait outside for their prey.

The moment that the young grubs appear they are grabbed by the Ants, pulled out of their sheaths, and cut in pieces. You see piteous struggles between the little creatures who can only protest with wild wrigglings and the ferocious brigands who are carrying them off. In a moment the massacre is over; all that is left of the flourishing family is a few scattered survivors who have escaped by accident.

It is curious that the Mantis, the scourge of the insect race, should be herself so often devoured at this early stage of her life, by one of the least of that race, the Ant. The ogress sees her family eaten by the dwarf. But this does not continue long. So soon as she has become firm and strong from contact with the air the Mantis can hold her own. She trots about briskly among the Ants, who fall back as she passes, no longer daring to tackle her: with her fore-legs brought close to her chest, like arms ready for self-defence, she already strikes awe into them by her proud bearing.

But the Mantis has another enemy who is less easily dismayed. The little Grey Lizard, the lover of sunny walls, pays small heed to threatening attitudes. With the tip of his slender tongue he picks up, one by one, the few stray insects that have escaped the Ant. They make but a small mouthful, but to judge from the Lizard’s expression they taste very good. Every time he gulps down one of the little creatures he half-closes his eyelids, a sign of profound satisfaction.

Moreover, even before the hatching the eggs are in danger. There is a tiny insect called the Chalcis, who carries a probe sharp enough to penetrate the nest of solidified foam. So the brood of the Mantis shares the fate of the Cicada’s. The eggs of a stranger are laid in the nest, and are hatched before those of the rightful owner. The owner’s eggs are then eaten by the invaders. The Mantis lays, perhaps, a thousand eggs. Possibly only one couple of these escapes destruction.

The Mantis eats the Locust: the Ant eats the Mantis: the Wryneck eats the Ant. And in the autumn, when the Wryneck has grown fat from eating many Ants, I eat the Wryneck.

It may well be that the Mantis, the Locust, the Ant, and even lesser creatures contribute to the strength of the human brain. In strange and unseen ways they have all supplied a drop of oil to feed the lamp of thought. Their energies, slowly developed, stored up, and handed on to us, pass into our veins and sustain our weakness. We live by their death. The world is an endless circle. Everything finishes so that everything may begin again; everything dies so that everything may live.

In many ages the Mantis has been regarded with superstitious awe. In Provence its nest is held to be the best remedy for chilblains. You cut the thing in two, squeeze it, and rub the afflicted part with the juice that streams out of it. The peasants declare that it works like a charm. I have never felt any relief from it myself.

Further, it is highly praised as a wonderful cure for toothache. As long as you have it on you, you need never fear that trouble. Our housewives gather it under a favourable moon; they keep it carefully in the corner of a cupboard, or sew it into their pocket. The neighbours borrow it when tortured by a tooth. They call it a tigno.

“Lend me your tigno; I am in agony,” says the sufferer with the swollen face.

The other hastens to unstitch and hand over the precious thing.

“Don’t lose it, whatever you do,” she says earnestly to her friend. “It’s the only one I have, and this isn’t the right time of moon.”

This simplicity of our peasants is surpassed by an English physician and man of science who lived in the sixteenth century. He tells us that, in those days, if a child lost his way in the country, he would ask the Mantis to put him on his road. “The Mantis,” adds the author, “will stretch out one of her feet and shew him the right way and seldome or never misse.”