The World That We Experience

You live in

the real world, but you rarely (if ever) see it. [42] Instead, you know only the

version that you experience. [43] The physical world is

whatever it is, but your experience of it is all your own. Part of

finding your power to be happy is in knowing that your experience

is your creation. You have the power to experience the world as a

place of happiness.

Your experience of the world results from

your perception of it. Because it is your perception, you are

responsible for the way you see the world. In your mind, the world

can be dark and loathsome, or it can be light and happy. It can be

full of things that make you miserable, or it can be full of things

that make you joyful. It can be heaven, or it can be hell.

Constructing Your World

The world that you see comes to you through

your physical senses. In each moment of awareness, you internally

construct your perception of the world based on the input from

these senses. In other words, from the raw material of sense

impressions, your mind constructs your world. From these

perceptions, you build and maintain an image of the world in your

mind.

Swami Satchidananda put it this way:

The entire outside world is based on your

thoughts and mental attitude. The entire world is your own

projection. [44]

You

interact with your image of the world. As long as your image of the

world is a more or less accurate reflection of the real world, you

can successfully interact with it. Your internal model of the

world, while not a perfect representation of it, usually enables

you to get from Point A to Point B in reality without much trouble.

[45]

It is important to understand that the world

you know is in large part a creation of your mind. If you believe

that the world, as you perceive it, is the way it is and is

unchangeable, then you cannot change it. You cannot change it even

if you mistakenly see the world as dark and unhappy, and sincerely

wish it were otherwise. If, however, you understand that your

perception of the world is largely of your own making, then you can

change your experience of the world by changing the way you look at

it.

When you realize that the real world is not

necessarily the way you think it is, you are beginning to know the

truth of life. And the more you know the truth, the more you are

aware of possibilities for happiness that may not currently be

apparent to you.

A Filtered World

The world as you see it is a filtered world.

You filter out of conscious awareness most of what happens around

you. You do this because you cannot be aware of everything that is

happening right now. This filtering process makes it possible to

live and function in the world, without being overloaded by all of

the images, sounds, and sensations that bombard you every second.

However, filtering also limits your ability to see the world as it

is, and casts doubt on the accuracy of what you think you know

about reality.

A great illustration of filtering is the

famous experiment described by Christopher Chabris and Daniel

Simons in their book, The Invisible

Gorilla. In this experiment, subjects were asked to

watch a short film in which two teams, one wearing white shirts and

one wearing black, passed basketballs among themselves. The

subjects were supposed to count the number of passes made by the

white-shirted team. They were supposed to ignore the players in the

black shirts.

Counting the passes required focus, and the subjects

filtered out much of what they saw. One of the things that many

filtered out was a woman wearing a gorilla suit who appeared on the

scene for nine seconds midway through the video. She thumped her

chest in full view, and then left. While thousands of test subjects

have watched this video, only about half were aware of the gorilla.

They were so focused on their task that they were blind to

everything else.[46]

How do we choose what to allow into

conscious awareness, and what to filter out? Most of the time, we

take in what we expect to see, or what we are looking for, and

filter out the rest. If you keep seeing and hearing the same things

every day, it is probably because you are looking for them and

filtering out everything else. For instance, have you noticed that

your drive to work looks pretty much the same every day?

A World Created by Care

In his

book, Time and Being, the

philosopher Martin Heidegger sought to identify the essential

“being-ness” of humankind. In other words, aside from the obvious

physical characteristics, he wanted to know the essence of what

makes us human.[47]

What makes you human, according to his

analysis, is the fact that things matter to you. You consciously

care about things. The defining characteristic of your existence in

the world is that you want certain things, you do not want other

things, and as for the rest, you are indifferent. In important

ways, you define yourself, and you define the world in which you

live, by caring. What you care about becomes the world you see. In

addition, your self-image is in many ways the image of all of the

things that matter to you.

Caring is so important that it creates the

world you see. As you move in the world, you see most clearly those

things you care about, and you disregard the rest. Even the

distance or location of things depends on how much they matter to

you. For example, if you see a friend across the street, that

person is, in important ways, closer to you than the stranger

standing next to you.

A Remembered World

The

world that you perceive is not only filtered; it exists largely in

memory. You create your perception of it mostly from

memory.[48] At any point in time, what

you think you see of the world is not what you see right now, but

what you remember of how it existed in the past. Let me illustrate

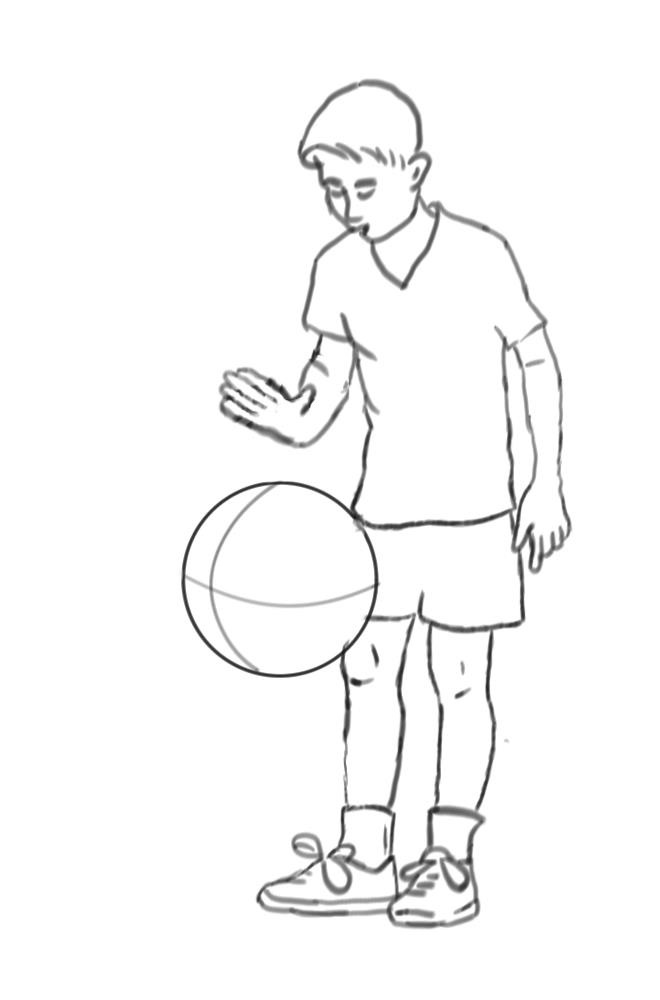

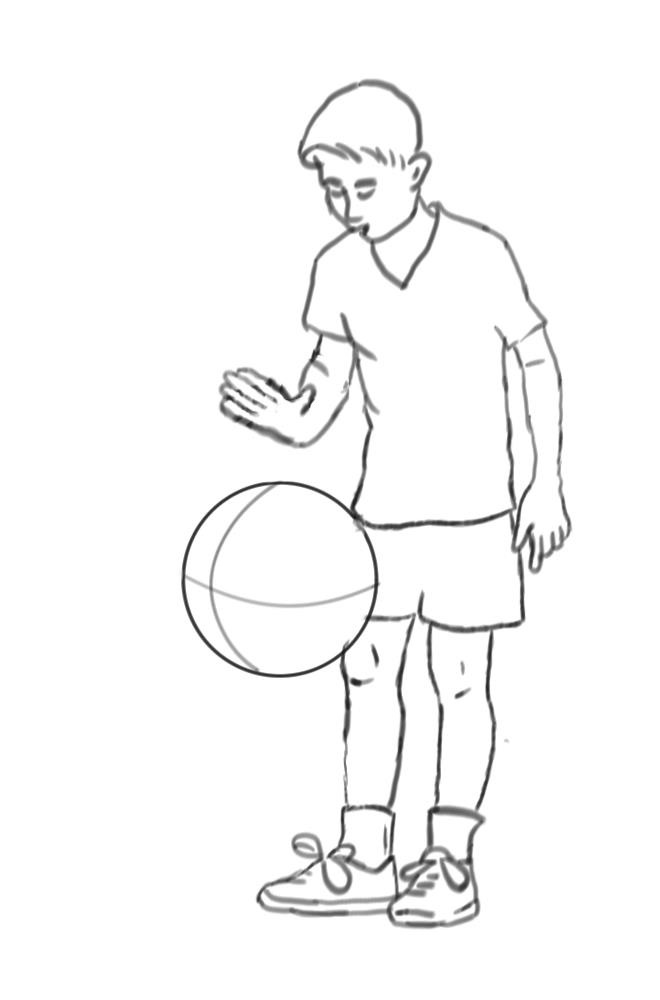

this concept using this picture of a boy bouncing a ball.

Assuming the ball is not stationary by

defying gravity or being attached to the boy’s hand, it is either

moving up or down — but which is it? Is it moving up or down? You

can guess, but it is impossible to know. It is as if you are

looking at one frame of a filmstrip. You can know if the ball is

moving up or down only by looking at the frames before or after the

one you are focused on.

The boy

with the ball illustrates the dilemma of human perception. As you

observe what is happening in the world, you see only one moment

(frame) at a time. You see only “now.” It is impossible for you to

see “now,” and the split second before “now,” simultaneously. So

how do you know what is happening? Very simply, you see “now” and

simultaneously associate “now” with your memory of the

past.[49]

If you see where the ball is now, and

simultaneously examine your memory of where it was 1/100th of a

second ago, you will know if the ball is moving up or down. While

you may assume that you see the ball bouncing “now,” in reality you

do not, because much of what you think you see now is what you

remember from the past.

Let us expand the timeframe of the boy and

ball, and assume that the frame you are now looking at is 15

minutes into a basketball game. As you watch the boy with the ball,

your mind may be recalling what he did five minutes ago, or how he

has played in other games. You may be speculating about what he

will do next. Your mind is dealing with so much remembered

information that what you see “now” may play only a minor part in

what you perceive and remember of this moment.

Problems with Reliance on Memory

As the boy-with-the-ball illustrates, the

way you perceive what happens forces you to rely on memory. Much of

what you think you see comes from your memory and expectations. The

world, as you see it, is not the world as it is. It is impossible

to see the world as it is because you are always limited to seeing

it frame by frame. Perhaps your memory of the previous frame is

accurate, and perhaps not. Perhaps the world changed from what it

was when you last looked at it; perhaps memory is faulty; perhaps

you remember the world from another time or place.

Not only can your perception of reality be

“off”; reliance on memory keeps your attention focused on the

contents of memory rather than on the world itself. If you are

looking at your memories, you are not mentally present. If you are

not present, you have no chance of seeing the world as it is. I am

not saying that the real world never reveals itself. If you smash

your finger with a hammer, you are suddenly very much aware of what

is happening. Most of the time, though, your attention is focused

on the past or the imagined future.

When you are not present to see reality as

it is, you limit your view of it to your mental construct of it.

You may have a distorted view of reality that you cannot correct

because you are not present to see it as it is. Distortions may be

negative or positive, but they are still distortions.

A Negative Bias

The

mind seems to have a negative bias when it comes to interpreting

and reacting to what we see. The bad things we see make more of an

impression on us than the good things. Negative information is

likely to have more impact on our final impression of something

than does positive information. As we look at the world, it is not

through rose-colored glasses. We tend to view the world as

something more hostile than it is. For example, evidence suggests

that, in close personal relationships, bad events have five times

the impact of good ones. [50]

One of the few areas where the bias may not

be negative is in our view of ourselves. Most people seem to

remember and emphasize the good about themselves, and downplay the

bad.

Some psychologists think that the negative

bias of the mind is adaptive. In the jungles and plains of 100,000

years ago, missing an opportunity for something good usually did

little harm. If you missed an apple on a tree, there would always

be another. However, if you missed something bad, that very well

could have been the end of you. For instance, you might have missed

a snake lying quietly on a branch by an apple. You could have

missed several apples, and still found another. But if you failed

to notice the snake — mortal, or at least grim, consequences.

Therefore, we evolved to be more alert to

the bad than to the good. It was an effective adaptation to a very

dangerous world. Of course, it was a world in which nobody expected

to live that long.

Today, we expect to live a long time. A mind

biased towards the bad and the dangerous is no longer adaptive to

current circumstances. Psychologists tell us that the mind that is

constantly on the alert for danger is unhealthy in the long term.

As we age, it contributes to the risk of heart attack, stroke, and

hypertension. In addition, a negatively biased mind means that a

long life will be, for many of us, an extended period of

unhappiness.

A dog bit Joanie when she was very young.

Whenever she sees a dog, an old memory stirs, and any dog looks

vicious to her. She lives in a neighborhood with many dogs, all of

which appear frightening to her. Joanie has a powerful emotional

desire for things to change in her neighborhood, and this

unfulfilled desire makes her unhappy. However, the distorted way in

which she sees things causes the unhappiness she experiences, not

the dogs.

Is Your Reality What You Think It Is?

Let us recap the discussion so far.

• Your perception of the world is based on your

physical senses.

• You go about the world filtering out much of what

you see.

• Most of the time, your attention focuses on the

contents of your memory of the world.

• Your mind tends to focus more on the bad than the

good.

Given the way in which you perceive the

world, how much can you really know about it? I hope you can

conclude that there is a lot more you could know, right now, if

only you open yourself to looking, listening, and experiencing the

world as it is. The indisputable fact is, things do not happen in

the way you think they do. You experience only your perception of

the world, which has profound implications for how you understand

and interact with it.

That we have created and are now creating

the world we see around us is a recurring theme of the Buddha. He

said:

We are what we think. All that we

are arises with our thoughts; with our thoughts, we make our

world.

He also said,

We are shaped by our thoughts; we

become what we think. When the mind is pure, joy follows like a

shadow that never leaves.

As

mentioned in Chapter 2 — and I believe it can’t be stressed enough

— Swami Satchidananda echoes these ideas, saying that, depending on

how you perceive the world, “The same world can be a heaven or a

hell.” [51] He said that we all have a

“magic wand” with which we can create our heaven (or hell) on

Earth.

Jesus

may have been referring to our inability to see the real world when

he said, “The Kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth,

and people do not see it." [52]

Knowing

that things may not be as they seem can provide insight into how to

react to what happens around you. [53] It may cause

you to doubt what you think you know about what is possible.

I believe that most people would be

surprised to know the extent to which human perception changes the

world that we see. My advice to them is the same as that of Hamlet,

who said:

There are more things in heaven and earth,

Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

[54]

The Cage

The internal image of the world, which we

create, is crucial to our survival. We evolved to create an

understanding of the world so that we can know how to thrive in it,

and predict what it will do. The problem is, our version of reality

also limits what we believe we can

do. Our version of reality is like a cage. It both protects us and

locks us in.

When I see a car, I see a real car, but to

understand what I see, I reference an image of a car that I keep in

my mind. My image reflects my experience of all cars. When I see a

car, or just part of a car, I can bring to mind a complete image of

a car like it. I also imagine things that the car is likely to do,

so that I can navigate around it. What I experience, therefore, is

more my creation than the reality of the actual car. However, my

ability to anticipate the movements of the car enables me to be

safe and effective in the world.

While a mental model of the world is

necessary, it can dominate and narrow the focus of our attention,

making it impossible to bring into awareness anything else. After

painstakingly assembling a detailed model of the world in the mind,

we lock ourselves into it. We lock ourselves in to a mental

cage.

One of the fundamental images about the

world that we create is what you think of as ourselves (the

self-image). Our self-image is necessary. As part of this self, we

carry images of ourselves, perhaps millions of them. We have images

for every age we were, and ideas about how we will be in the

future. We have detailed information about how to do what we do. We

remember how we have failed in the past, and have ideas about how

we can avoid failing in the future. We remember the times we were

happy in the past, and have beliefs about what it will take to make

us happy in the future. We have information about thousands of

things we like and do not like. We have millions of bits of

information about our work or the subjects we study in school, our

friends, our enemies, and everything else we need to know. We have

“a take” on just about everything, and little inclination to do

“double takes.” The mind is complex beyond imagining, and we carry

all of this within us, referring to it constantly.

After creating this detailed image of

ourselves, we lock it down. A fixed self-image is of course helpful

for getting around in life. Life would be beyond difficult if we

were to wake up every morning wondering who we were and what we

could do. However, this self-image is also a cage, its imaginary

bars are the images that we have created.

You need a strong self-image to be effective

in the world. However, the stronger the self-image (the more

impregnable the cage), the harder it is to change the way you see

yourself and the world in which you live.

The stronger the focus on your image of

yourself, the more isolated you are. In the play Peer Gynt, Henrik Ibsen observed this about

inmates in a “madhouse”:

Here we are ourselves with a

vengeance;

Ourselves and nothing whatever but

ourselves.

We go full steam through life

under the pressure of self.

Each one shuts himself up in the

cask of self,

Sinks to the bottom by

self-fermentation,

Seals himself in with the bung of

self,

And seasons in the well of

self.

No one here weeps for the woes of

others.

No one here listens to anyone

else’s ideas.

We are ourselves, in thought and

in deed,

Ourselves to the very limit of life’s

springboard.[55]

Mindfulness: Seeing the World as It Is

To see reality as it is, you have to learn

to be comfortable with being in the absolute moment. Being in the

moment gives you the power to see beyond the normal confines of

your mind. Being in the moment allows you to break free of the

limits of your everyday way of thinking. Without these limits, you

can pull your attention away from the trap that is your mind, and

shift your attention to happiness.

It is important to remember that the world

you see and interact with is the image of the world that you have

constructed in your mind. You cannot avoid this fact. However, by

knowing and being steadily mindful of it, you can perhaps learn to

see the world with fewer distortions.

At a minimum, you can learn to see the world

as it is right now; not as you remember it to be, as you want it to

be, or as you fear it might be. As I discuss in Chapters 8 through

10, you can learn to be mindful of the present moment through the

practices of mindfulness and meditation.

In many

ways, to be mindful is to see the world as a child, with all of the

freshness and wonder that this entails. [56] Each sunrise

is a fresh experience, and the stars at night are always new and

bright. Your spouse or partner is always new and exciting. Your

friends and children are always interesting, even when they

repeatedly do and say the same things.

Changing Your Perception of the World

If you change the way you perceive the

world, you will change the world that you experience. Merely by

changing your perception, you can change the world from one that is

dark to one that is light. You can change a sad world into one that

is happy. You can learn to change your perception, and in so doing

create the happy world that you want.

You change the way you perceive the world by

changing your internal experience. For example, you may change that

experience from unhappiness to happiness, or from selfishness to

selflessness. These changes affect what you care about in the

world. According to Heidegger, what you care about determines, in

large part, what you see in the world.

A

Christian mystic, Brother Lawrence, said, “God is everywhere, in

all places.” [57] Brother Lawrence changed his

internal perception of the world, and as a result, the world for

him became a much better place.

Jesus said that heaven is all around us -

and “within” — but we do not see it.

You can change your experience of the world

by learning to shift your attention from your self-centered desires

to unconditional happiness. You can harness the power of your

natural desire for happiness, and aim it directly at what you

seek.

By shifting your attention to happiness and

letting go of self-centered desires, you change what you care

about, and thereby change your world. The world you see will appear

different to you because as you change what you care about, you

change what draws your attention.

Brother Lawrence cared about God, and his

attention focused on God in all things. Likewise, if I am in a

positive mood, I see happiness all around me.

Creating the Substance of Your World

Some believe in a creator God or Divinity

that created and continues to create the real world. In addition,

some believe that each one of us is God and creates his or her own

reality. Some hold that reality itself is an illusion.

I do not have any conscious experience of

creation taking place, of willfully manifesting my own reality.

Perhaps I create things unconsciously. However, my unconscious is

unknown to me. I cannot say what kind of creative activity takes

place in the deepest part of my being. Therefore, I cannot say

anything about the creation of the world by a creator God, and I

cannot say anything about my personal creation of the world.

I do acknowledge my personal responsibility

for my perception and experience of

the world. Regardless of how the real world comes into being, the

world as I experience it is my creation. And because I create my

perception, I can change my perception, and thereby change my

experience of the world. This power of perception is something you

should not take lightly. Out of this power comes your ability to

find lasting happiness.

I cannot say anything about creation of

reality because it is beyond what I can consciously experience. In

this book, I focus only on what we consciously experience. How

substantial reality is created or changed I will leave to others to

explore and discuss.