For the majority of my admission, my neutrophil count was at zero. Each day, I waited for my neutrophil count to shoot up. Labs were drawn at approximately five in the morning. After a few hours, I was eager to find out what my lab values looked like for the day. But nothing was improving. My counts remained stagnant for over a week. I was constantly reminded that it would take time for my bone marrow to recover from the treatment regimen and that everyone recovers at a different pace. I tried to compare myself to other patients and how quickly or slowly they recovered.

I received daily injections of a medication called filgrastim which was supposed to stimulate my bone marrow to create white blood cells. Whenever Sean gave me the injection, he said,

“Alright man. This is the one right here. This is the one to get that neutrophil count going.”

I believed him each time. But each morning, I would be disappointed by the results. Once my neutrophils finally started to bump up from zero, it was the slowest incline I could have imagined. It started at 5, moved up to 15, then back down to 10, before bumping up to 20. It teeter-tottered its way ever so slowly in the upward direction. It was discouraging for the number to not just shoot to the moon so I could get out of there.

88

I failed to recognize the importance of the progression. Sean taught me that no matter how small progress may seem, it is worth getting excited about. He would pop into my room each day that he took care of me as soon as the neutrophil count came in. I could tell how excited he was to tell me the number. He would ask me to take a guess. Some days, my guesses were underwhelming and I aimed too high. Other days, my guesses exceeded my expectations.

Sean found joy in finding ways to make me smile. We both got hype each time the neutrophil count bumped up. One could argue that he was even more excited than I was! He is a man that I will remember until the day I die because he was so influential for me during my time of need. I have to give credit to Sean for helping me knock down that second wall. He helped me take a step back to realize that I was progressing. It wasn’t going to be a miraculous increase overnight, but a slow and steady progression. With that, my attitude brightened just enough to keep me pushing toward discharge day.

Joanne taught me that there is a takeaway from each day. Something we could reflect on to see what we improved on or what we could do differently the next day. I kept looking at the end goal of being discharged from the hospital. I still was on mostly IV medications, IV nutrition, and I could barely eat. I had a long way to go. Joanne would pop into my room, even if she wasn’t my nurse for the night, just to joke with me and make me laugh. If I was discouraged with how the day went, she would say to me, “But look at how much better you did than yesterday.”

She was my hype woman. If she saw me walking in the hal way, she would call me “superstar.”

I smiled just in anticipation of what she would say to me when she saw me. Several times she sat right next to my bedside late in the evenings to try and cheer me up. On days she was off, she made sure the other nurses on the floor were checking in on me and saying hello in the hallways. She always told me that what I was going through was difficult, but I was able to handle it. It was alright if I didn’t always feel strong and capable of handling the situation. No matter what, I was going to make it through. The storm will eventually end. Joanne picked me back up every day I fell trying to break down the third wall of the transplant stay.

89

Joanne also taught me it is okay to ask for help. I made myself feel ashamed for not being strong enough to handle the struggles on my own. But she continuously told me that she would be there for me if I needed her. Al I had to do was ask. Asking for help isn’t giving up, it is refusing to give up. She came in to reassure me that the struggle I was currently in wouldn’t last forever. Because of her, I learned from the takeaways each day and used them to my benefit the following day. I would ask myself, what went wel today? What didn’t go so well? Acknowledge your progress and take pride in it.

But don’t forget there is always room for improvement.

What wasn’t going so well was how I was eating. I lied about how much food I was actual y consuming. I knew that being able to eat would help me get out of the hospital. But I just couldn’t eat.

The sight of food made me want to throw up. The team tried weaning me off of IV medications to get me used to taking pills. But when a pill cup was placed on my end table, it made me dry heave. I hated looking at those giant pills. I hated trying to swallow them even more. A dietician stopped by my room every few days to track my progress.

I had a piece of paper hanging in the front of my room where I was supposed to write down what I ate each day. Each morning, I ordered a blueberry muffin. I took the muffin out of the wrapper, threw it in the trash, and covered it up with tissues. Then, I wrote on my meals tracker that I had a blueberry muffin for breakfast. I knew it was the wrong thing to do but it was an act of desperation. I couldn’t finish the muffin even if my life depended on it. It is unbelievable how tiny my appetite was during that hospital admission. A day’s worth of eating would barely equate to one meal that I would have today. My stomach had to get readjusted to be able to withstand different tastes, textures, and consistencies.

I came up with this absurd idea to get my pills down. It was disgusting, but hey, it worked for a little while. A snack that helped me get by was pretzels and peanut butter. I had those little pretzel rod snack packs stashed over on the windowsill in my room. I asked the nurses to bring in some of the Smucker’s peanut butter cups that they kept in the pantry room. I had three or four cups stacked on my table at all times.

90

Before I tried taking a pill, I shoved a glob of peanut butter into my mouth along my cheeks and in front of my two front teeth. The peanut butter served as a distractor to take my mind away from the pill that was about to be placed on my tongue. Instead of triggering my gag reflex, my mind gravitated towards the need for a drink because the thick peanut butter dried out my mouth. I quickly took a swig of water or ginger ale, put the pil in my mouth, swallowed it, and hoped I didn’t puke it back up. If the pil didn’t go down on the first try, I coughed it up. Those three posaconazole still proved to be my worst enemy. I coughed up those tablets countless times. I know this is a big “no-no”, but on days I was really feeling lousy, I tossed those three pills in the trash with no regret.

The doctor who was on service for most of my hospital admission was being switched over to the care of another doctor. He wasn’t just any doctor; he was the head honcho of the stem cell transplant unit. The filgrastim injections were finally paying off and my neutrophil count was making leaps. You know that made me, Joanne, Sean, and the rest of the team hype.

With my neutrophils reaching the levels they needed to be at, the word “discharge” final y was getting thrown into conversation. By now, I had already spent over a month in the hospital which was my most extensive stay yet. The truth is, I lied about how I was doing most of the time there. Throwing away food, not showering, and vomiting all behind the back of my care team. There were so many ups and downs. For a moment, I thought I was getting better but then felt drained again the following day.

After a solid day of eating (which wasn’t saying much at the time) and getting some laps around the unit, I threw up after only walking a handful of laps. I frantically threw paper towels and tissues over the vomit because I didn’t want anyone to see it. I knew discharge was close and I didn’t want anything to mess that up for me. On the first day the head honcho was on service, I tried to be a showoff and walk a few laps before he came in to see how I was doing. My motto was, “I won’t give them any reason to keep me in here.”

I sat in my usual spot by the window in the hallway for a break when the physician assistant asked me to head back to my room to meet with the team. The doctor was a cool dude. He knew I had been begging anyone I could to get discharged. But he had some reservations about that. He told me 91

that some patients get sent home too prematurely and end up being readmitted due to malnutrition.

So, they made a deal with me. They would take me off of the IV nutrition and see how I did with taking my pills and eating my food for two days. Then, finally, discharge could be considered. Bingo.

I am not proud of it, but I wasn’t truthful about my food consumption in the hospital. I took ant-sized nibbles from peanut butter and jelly sandwiches only to throw them in the trash minutes later.

But, I chalked it up on my meal sheet as a full sandwich. For my pills, I knew how important they were for me to take so I forced them down. There was never a day that they all went down easy. I saw the light at the end of the tunnel which served as my motivation to take bites of food when I could and take all of my medicine. I knew I still needed hospital care but the quality of life there was just too poor to sustain for an extended time. I fell into the same mindset as my previous long hospital stays. I thought being sent home would magically cure everything again.

Since I was off of my IV nutrition and it was almost time for discharge, I was able to get the catheter from my chest removed. “Oh, it isn’t painful! It is just like getting your PICC line removed. They just pull it right out,” I was told by everyone. Then again, I don’t think any of those people ever had a catheter placed into their chest before. I remembered how painful it was having it put in and I would imagine it was going to be painful on the way out too. I was taken down to the interventional radiology department in the hospital. I was placed in a room with a curtain dividing it in half. Another patient was laying in a bed on the other side.

“Are you ready to get that Hickman taken out today,” asked the nurse.

“I cannot wait,” I responded without hesitation.

She cut out the sutures holding the catheter in place and intensely cleaned the area.

“How long have you had this in place,” she asked.

“About a month,” I responded.

“Alright, we may not even have to numb the area. Sometimes when it hasn’t been in too long, we could pull it right out.”

92

The doctor came in to remove the catheter. He insisted on using a few shots of lidocaine to numb the area. He wanted the removal to be as comfortable as possible for me. The first shot of lidocaine went deep into my chest. Oof. Alright. That one kind of hurt. For the second shot, he lifted the piece hanging out from my chest and poked right underneath. Damn, that one hurt too! Now it was time to get the tube pulled out of me.

The doctor started pulling on the catheter and it hurt like hell. I couldn’t look down at my chest to watch it all unfold. Deep breaths weren’t doing me any justice. I was wincing in pain. “Last little bit is the worst part,” he said to me. I squeezed my eyes and gripped the sides of the bed as tight as I could.

“There we go!” Just like that, a long piece of tubing was being pul ed from my chest right in front of my eyes. It felt like he had just ripped my heart right out of my chest.

“Are you alright?”

“Yeah. Yeah, I’m good.”

I looked down at my legs and they were quivering. The whole transit back up to my room I kept thinking about how shocked I was about the pain I just experienced. But I was now one step closer to getting out of there.

The next morning, the team came in for their daily round with me. “Congratulations! I’m going to let you go home today. I know you’re going to do great,” said the doctor.

Let’s go! Final y! It was time to get out of there!

What I had been through during those five weeks was nothing short of torture. The fourth and final wall of the transplant stay was knocked down with the doctor’s words. It was time to begin the long road to recovery.

93

Recovery

I sat by the window in my apartment with the warm spring air breezing on me. I snacked on a few pieces of watermelon before I had to start knocking down some of the pills I had to take. I had twenty-one pills to take each day. Twenty-one pills! Even taking a short nap put me behind schedule for my medication. On top of those oral medications, I had to do daily magnesium infusions. The tacrolimus medication I was on impaired my kidneys’ ability to reabsorb magnesium. So, every day I had to get hooked up to a pump for four hours to replenish my body’s magnesium stores. Even with receiving four grams of magnesium each day, I was barely in the normal range.

Madison kept a written log of how I was doing each day during my beginning weeks at home.

If you look in the notes, you’l see a lot of me saying, “I feel like shit.” I stil wasn’t getting much food down. The medication kept making me gag. Looking at my pill box made me want to run for the toilet.

I began to experience some more side effects of the conditioning regimen. My hands and feet burned like hell. It must have been damage to my skin from the radiation. While at rest, it wasn’t bothersome.

But washing my hands, wearing socks and shoes, walking, and other simple parts of life hurt me. Those weren’t the only parts of my body that were burning either. Each time I urinated, that burned like hell too. You would have thought I was peeing out fire. Each time, I tensed up and held onto something to try and resist the pain.

Laying in bed at night, my head felt like it was spinning. Just like one of those nights where you realized you had too much to drink, I woke up each morning feeling the same way. I let myself sleep as late as I could. It’s not like I had anything else to do with myself except for taking medications. Only about a week in from being out of the hospital, I started to crack again. I grew more frustrated with myself each day. I choked on one of my bigger pills and I was dry-heaving. I cried because I couldn’t 94

handle it. Any of it. There was too much responsibility for me trying to heal. Taking medication, trying to eat, trying to sleep, trying to use the bathroom, none of it was easy for me. I cried hysterically which led me to my head hanging in my toilet puking out the little food I had in my system for the day. As soon as I finished puking, my face felt swollen. When I looked in the mirror, I saw a puffy face looking right back at me.

Here we go. One week out of the hospital and I was already spiraling downward. This was on me for lying my way to a discharge. I knew it was going to come back and bite me in the butt. Madison and I agreed we had to call someone and I had to be checked out. We made a drive back over to the hospital so I could be seen in the emergency room. As I was waiting in the triage room, I rocked back and forth because my feet were hurting me so badly. I got ice packs from the nurse and placed them underneath my feet hoping to ease the pain.

Madison and I sat in the neutropenic precaution room to keep me away from infection risk while we waited for a bed to become available. We brought my pill bottles with us so I could stay on schedule with my medication. For 3 hours we waited in that room. Nonetheless, we didn’t get to see a doctor. I was upset that we wasted so much time waiting for help, but nobody came out for us. The swelling did start to go down, so we made the team decision to just go home. We made the walk over to the parking garage in the rain so we could go home and get some rest. We were going to have to wake up tomorrow and try for a fresh start.

95

I remember laughing at my mom when she told me she wanted to take me to my doctor’s appointments after my transplant. I thought I would be easily able to drive myself over like I always did.

When it came to it, I wasn’t comfortable doing anything on my own. I needed someone to drive me over and I needed someone to be with me as I walked.

I arrived at the cancer center for my first appointment to see the nurse practitioner. She is an expert in bone marrow transplantation and would be caring for me for the foreseeable future.

My mom and I sat down in the room with her. She was a very energetic and lively person. She asked a lot of questions to gauge how I was feeling. I told so many lies. I made it out to seem as if I was doing much better than I really was.

“I don’t feel too bad honestly.” Lie.

“I’ve been moving around okay.” Lie.

I didn’t want to accept how bad I was doing, in my eyes at least. I asked, “Is there anything I can do for some physical activity? Could I ride a bike? How about playing golf?” Asking to ride a bike had both my mom and her laughing at me. “Maybe with your helmet on,'' she jokingly replied. My face started to turn red. “I don’t want you playing golf either. Not with that PICC line in.” My mom continued to laugh that I even asked about doing physical activity. My face continued to turn red hot and kept my eyes focused on my feet.

My mom asked the nurse practitioner, “Could he drive a car?”

“Yes, he can do that.”

96

Both began laughing once again. This was the first time at a doctor’s appointment that I wanted to get up and leave. It was more so a sit-down with two moms laughing at one of their kids because he wanted to do too much. I wasn’t being encouraged to get back to my normal form. I was being encouraged to keep a sedentary lifestyle and wait for time to pass to heal me.

The discussion continued. The good news was my donor cells had almost fully taken over my bone marrow at that point in time. Everything was going according to plan in that aspect. The bad news was the PICC line was going to stay in my arm for at least another six months. Magnesium infusions would continue for at least six months. Immunosuppression would continue for three to six months. In summary, I was in for a rough stretch.

A day that was heavily emphasized was day 100. That day marked several milestones. I would plan to start coming off of my immunosuppression, I would be able to eat takeout food again, and another bone marrow biopsy would be scheduled to examine how my bone marrow was functioning. It created a false narrative that after that day, everything would return to normal.

On the way out to the car, my mom told me she was so happy she could cry and asked me for a hug. After I hugged her, I asked, “What is it that you are so happy about?” I questioned in my head, that I have to keep my PICC line in for the next six months? That I have to be on all these medications?

That I can’t do any physical activity aside from walking?

I failed to realize in that moment that I had plenty to be grateful for. The transplant was going how it was supposed to. I didn’t recognize that. I focused on what I wanted. Not what I needed. What I needed were those stem cells to start going to work in my body and they were. But I continued to focus on the medications I didn’t want to take. The lifestyle I didn’t want to live. Everything that I wanted to do, I couldn’t. My time would come, I just had to be patient. The conversation with my nurse practitioner that day knocked down the first wall of the recovery process outside of the hospital. It set realistic expectations for how my recovery was supposed to go. Although I was unhappy with how the next few months were scheduled out to be, I had no control of it. I just had to find a way to put my head down and do what I was told.

97

My initial interaction with my nurse practitioner does not at all represent what my relationship turned out to be with her. She is an incredible and caring individual who is fantastic at her job. Her livelihood was not something I was able to appreciate at first. I was unable to recognize that she was not actually laughing at me at that first appointment. Both she and my mom knew I was being too ambitious right out of the gate from transplant. She used her energy to connect with my Mom and I.

She did her best to shed light on a dark situation. She cheered me every step of the way and guided me to a successful recovery. I will always be grateful that I was under her care after my transplant.

98

While at home, I woke up late each morning. I hardly ate my meals, and I didn’t get up off the couch for much. Just like I did in the hospital, I laid on the couch under a blanket while staring at the wal ahead of me. I wouldn’t say I was depressed at the time, but I didn’t look forward to a new day when I hopped into bed at night. I always hoped I would wake up one morning and all of my issues would magically resolve. I didn’t understand that I had to take control of the situation. There were things I could control but I didn’t want to step up to the chal enge. I didn’t make changes to myself. And, because of that, no changes were made to my problems.

I had a memorable bad day that summer. It was a Sunday and I had to pick-up medicine from the pharmacy at the hospital before they closed at two in the afternoon. Madison and I hopped in the car, and I pulled out of our parking spot. As soon as I put the car in drive and started moving, something felt off. I hopped out of the car to see if something was wrong. I looked at the back right tire and saw a screw lodged into the rubber with the wheel completely deflated. You have got to be kidding me. Life was poking fun at me.

I pulled the car over and started to work on getting the tire off and replacing it with the spare tire. The heat was aggravating my skin sensitivity and bending down on the hot concrete didn’t make it feel any better. As we tried lowering the spare tire down, the pul ey was rusted and wasn’t loosening the tire for us to take off. It was close to when the pharmacy was closing, and I stil hadn’t eaten anything. Madison offered to hangout by the car while I went to make a quick snack. My gourmet first meal of the day was one egg served with a piece of toast with no butter. With the anger I was feeling 99

from my flat tire, I ate my meal too quickly. Not long after, that small meal came right back up. So much for having my first meal of the day.

We finally were able to get the tire fixed but not until after the pharmacy closed. Sometimes, life will really test your patience. And that day, I lost. As I sat on the hot Philadelphia sidewalk waiting for help to get that spare tire off of my car, I bowed down to that troubling second wall.

One of the most influential lessons I have ever heard was one said by Jay Shetty. To paraphrase what he said, there are three things you can control when working toward a goal of yours.

And then, there is one thing you can’t control. What you can control is your preparation, your practice, and your patience. What is beyond your control is the result. However, within your preparation, practice, and patience IS the result.

In those beginning steps of my road to recovery, I was not cultivating any of those three aspects into my daily efforts. As my dispiriting conversation with my nurse practitioner and flat tire demonstrated, I had difficulty staying patient. I did not prepare myself for a new day before going to bed either. I hopped into bed and rolled out whenever I felt like it the next morning. And for practice, I had no habits in place to better my chances at a smooth recovery. I did a whole lot of nothing and expected something in return.

My weight continued to plummet. When I went to see the nurse practitioner, she was worried about my weight too. She made comments about how skinny I looked each time. I dropped down to my lowest weight throughout the whole process which was a feather-light one hundred and thirty-eight pounds. With no progression in my dietary intake, it was time to result to dronabinol once again.

Dronabinol played a monumental role in my recovery by allowing me to eat substantially more.

My calorie intake was on the rise. I still struggled with more complex dishes, but I was able to get a handle on basic meals. I started to mix in my own protein shakes to get in additional calories and protein. I had a ten day stretch where I made a shake to drink each day. By the end, I was already getting sick of them.

100

Although dronabinol helped me eat, it didn’t help me get off the couch. The additional THC side effects were kicking-in. My mind constantly raced about the most random memories which made me laugh every time. I found myself perusing through the internet and watching YouTube videos just like I used to. A funny moment I want to share with you is when I was scrolling through YouTube high as all hell one day from the dronabinol. Once I explain the story, you will understand the pointless videos I got myself into watching.

I stumbled upon a video called, “Golden Retriever Came Across a Deer then Started a Game of Chase” (I bet that is even worse of a title than you were expecting). I scrolled through the comments, and someone posted, “Just read that title as a game of chess and my high ass was literally waiting for them to play chess.” I appreciated that comment because now I knew I wasn’t the only dude who was high and found that video. By the way, you could check out the video yourself to see if the two end up playing chess together.

Dronabinol was helping my appetite which resulted in more energy for me. I felt well enough to try to work on schoolwork to keep myself occupied. The professors at school were allowing me to make up schoolwork from the spring semester during the summer months if I chose to do so. I was very grateful for their flexibility with me. While reading over school notes, I unconsciously took sips of water and snacked on granola bars. It also gave me a rhythm to my days. Approaching each day with a set plan is what I needed most to help me recover. My preparation began to come into place.

Making up pharmacy courses over the summer wasn’t easy. I already had a tough schedule, and adding in courses like biostatistics, pharmacokinetics, and pathophysiology & therapeutics of the cardiopulmonary system added to the toughness. These courses were already difficult enough by themselves. Some courses didn’t have any recorded lectures for me to follow along with. The professors were willing to meet with me whenever I felt the need to, but other than that, I was on my own for trying to teach the material to myself.

I remembered that this wasn’t the first time I was on my own. And thankfully, this time, I wasn’t both alone and fearing for my life. Catching up to the school curriculum was difficult but I remembered 101

it wasn’t a life-threatening circumstance. To me, it was just a normal, everyday challenge. It was nothing in comparison to what I had been through before, but I was going to use the same approach as I did in the hospital.

I worked diligently to be as efficient as I could to knock out the coursework. In pharmacokinetics, I had no lectures to listen to. Just as I had stared at the wall in front of me in the hospital for hours, I stared at those PowerPoint slides endlessly trying to make sense of them. I practiced so many calculations, quizzed myself on the material, and talked through scenarios out loud. I was gracious that the professors met with me over Zoom for any questions I had.

Over the rest of the summer, I continued to review lectures, complete assignments, and take online quizzes and exams. Handling both schoolwork and my health was heavy to carry, but I continued to walk with it. My health was always my number one priority, but I would argue that being able to take those classes improved my health in itself. Working towards something each day made me feel so alive. I was slowly beginning to realize this, but one day I had to work each day in order to recover from the transplant as well.

An important lesson that I learned is to do the hard task of your day first thing in the morning.

With the daily magnesium infusions, I created self-induced anxiety by trying to get my infusion done during the middle of the day. I hated carrying that bag around during my busiest hours. The tubing hung low from my arm which caused me to bump into it with my feet while walking. The tug on my arm wasn’t a pleasant feeling either.

One day, Madison asked if I could run across the street to get something for us at the corner store. It was just a few steps from my door so I figured nobody would even notice the tubing sticking out from my arm. As soon as I walked into the store, my pump device started to beep indicating there was air in the line that needed to be cleared. Instantly, I had three to four sets of eyes looking at me.

Those poor people probably thought I was going to blow the place up.

I panicked. I quickly stepped out of the store to silence the pump before going back in. After that day, I came to the conclusion that I put the infusions off each day even though I knew I had to do 102

them. Waiting until later in the day didn’t solve anything. It actually made my days worse. Which is why it was important for me to get it done as soon as I could each morning. So, that’s what I did.

By finishing the hard step of the day right away, we set ourselves up for success. I always like to think that the outlook of our day is determined by how we spend our first hour. If we wake up only to scroll through our phone in bed, we set ourselves up for a lazy and slow start to the day. If we start off by completing something we aren’t looking forward to, everything else in the day feels easier. We feel motivated and energized to progress through the day. Otherwise, we push off that one thing that we real y don’t feel like doing as late as we can. Or, we don’t do it at all.

Around the fourth of July is when I felt a change in momentum. I was eating more than before, I didn’t have to take as many pil s, and the pain in my feet were beginning to subside. School work was keeping me busy, and I wasn’t such a couch bum anymore. I was up and moving around the apartment to grab my own snacks and drinks. It was the first time I felt like “someone” again.

When I visited the doctor, they assessed for graft versus host disease. During the first one hundred days is when patients are most likely to experience this. The “graft” meaning the newly introduced immune cells in my body, and myself being the “host”. With this, the immune cells recognize a person’s organs as foreign causing an immune reaction. The most common places this could occur is with a person’s skin, liver, stomach, or intestines. After getting out of the shower one day, I noticed small red bumps on my forearms and hands. I knew what it was right away… it had to be graft versus host disease.

I sent pictures to the doctor’s office, and they confirmed that it was most likely graft versus host disease. I was prescribed a steroid cream to put on the affected areas. The cream worked really well as the bumps faded away shortly after. But after a week or two, my stomach started bothering me. My appetite that was once improving, diminished once again. Anything and everything I ate went right through me. To give some context, I once had to use the bathroom almost ten times before noon. The providers concluded that my graft versus host disease was now affecting my gastrointestinal tract. To 103

treat it, I started on an oral steroid called budesonide. Budesonide was taken three times daily which wasn’t enjoyable, but it helped my stomach tremendously.

For those who have never been on an oral steroid before, they certainly make you feel more awake and energized. The mornings of me rolling out of bed late in the morning suddenly turned to walks to the park at six or seven in the morning. The steroid allowed me to regain the energy I lost from my treatment. I had an extra “pep in my step”, as the kids say. The small dip I had in my road to recovery was rejuvenated. My appetite improved so much that I hardly had to rely on dronabinol anymore. But, with the combination of budesonide and tacrolimus came its own issues.

Madison and I went for a bike ride up to center city for a fun and relaxing day with one another.

With my small appetite, my stomach started growling so we grabbed a breakfast sandwich from a nearby cafe. The sandwich was a big test for me because there were a lot of ingredients on it. Bacon, egg, cheese, tomato, and avocado. This was a big jump from what I was accustomed to. But damn did the sandwich hit the spot.

Later that day, I remember feeling nauseated with tightness in the back of my neck. The nausea intensified and my head started throbbing. As usual, I found myself with my head above my toilet puking violently. Madison and I didn’t know what to think of the headache. I asked myself, “Was it the sandwich that caused this?” I sat in my recliner with my head pounding so much that I couldn’t keep my eyes open any longer. Any electronic screen bothered me. Lights and sounds made me want to go right back into the bathroom to vomit more. The symptoms I had experienced aligned closely to those of a migraine attack. The only thing that eased my pain was sitting with all the lights off in pure silence.

Then, I closed my eyes and hoped it all would fade away.

As I alluded to before, day 100 was a big landmark for the post-transplant recovery period. It meant another bone marrow biopsy, potentially the start of a taper off immunosuppression, and cutting down on my medication list. I had day 100 circled in the back of my mind the whole summer. For me, it signified the start of me being myself again. The main issue I was focused on was my appetite. Many 104

times, people told me that by day 100 or around that time, the appetite usually starts to come back around.

But as day 100 approached, I didn’t experience any noticeable improvements. My bone marrow biopsy returned perfectly normal which my family and I were thrilled about. Some of my preventative medications were discontinued so I was able to cut down on my pil count each day. The news I wasn’t thrilled to hear was that I wasn’t close to getting my PICC line removed yet. I had to be off of my daily magnesium infusions for that step to occur. For my magnesium levels to return to normal range, I would most likely have to be off of my tacrolimus. The tacrolimus was going to be around for a few more months still so that meant continued magnesium infusions each day and of course, the PICC line staying in my arm. Eventually, I would be moved from a four-hour daily infusion to a two-hour daily infusion. But for the time being, I had to stick it out with the PICC line and get the magnesium that I needed.

It was after that appointment that made me realize that there was no set day that would make me feel like me again. There was no day that everything was supposed to fall into place. I had to go for it myself. All of that summer, I waited for that “snap of the fingers” to turn it around. Many of the limitations I had put on myself were self-imposed. Nobody was telling me I couldn't put weight back on.

Nobody said I didn’t have the strength to go on a long walk. Nobody said I wasn’t able to be up on my feet for longer than fifteen minutes. But I told myself these things and that was the catch. I had to believe in myself before I truly believed in my own ability.

105

The start of the new school year was right around the corner. With COVID cases being down in the area, classes were back in-person. I was so nervous about going back to class on campus. I was afraid of getting sick from being around others. I still had my PICC line in, so I had to wear my black arm sleeve at all hours of the day. I didn’t want people to look at me any different because of it.

In fact, I didn’t want people to look at me at all.

During the summer months, I always wore a pair of gym shorts and a tee shirt. At that point in time, I had not worn a pair of khakis or jeans in months. I pulled out a pair of khaki shorts to try them on because that’s what I planned on wearing to school at the start of the semester. Poof. My shorts slid right down my legs as I buttoned the waist. I lost so much weight that my old clothes no longer fit me.

It was time for the first day of class. I didn’t feel confident in myself going up to school on my own. For months, I went everywhere with someone else. I felt I needed backup in case something went wrong. From being isolated in a room by myself for hours on end in a hospital bed, months later I walked into a classroom with over one hundred other people. I felt “out of the loop” socially. I was put in such extraneous circumstances throughout treatment, so I didn’t get to chat much with other people.

And when people did talk with me, many times, they were asking about my health. In a way it felt nice to be back amongst other people, but I also felt so different.

The Ryan Scanlan that walked into that school two years ago looked and thought completely different from the Ryan Scanlan walking into the school that day. I had to convince myself that it was 106

alright. Some people were surprised to see me and asked how everything was going. “You look a little more thin” and “What is that sleeve on your arm” were some of the comments I heard.

My insecurities about my appearance started to itch me again. I know none of those comments were meant to be offensive, but I personally wasn’t happy with the way I looked. The problem was I still cared about what people thought about me. There is a quote I once heard that relates to this situation. I can’t attribute the exact person that said it, but it goes something along the lines of, “When you’re 20 you care what everyone thinks. When you’re 40 you stop caring what everyone thinks. When you’re 60 you realize no one was ever thinking of you in the first place.”

To ease the social anxiety I was feeling, I remembered everyone is the main character in their own story. As much I tried to convince myself that everyone was looking at me thinking, “What happened to him?” Everyone was showing up to class with their own thoughts, problems, and feelings associated with their own life. How that kid that used to have nice blonde hair that suddenly went bald is not a thought people would hold on to (at least I hope not). Most likely, the other students noticed I looked a little different. But five seconds later, they would forget I ever walked into the room in the first place.

It was a five-minute walk to get to the subway each morning for school. The subway ride took roughly twenty minutes which was followed by another five-minute walk. So, we were looking at a thirty-minute commute each day. Not bad at all, for most people. But for me, my stomach just knew when I was far away from a bathroom. As soon as I reached the “point of no return” as I would like to cal it, meaning I was too far away from my apartment to turn back around, I had the strongest urge to have to use the bathroom. It was not your typical, “I could hold this in for a bit longer.” It was full blown, “I need to use the bathroom right this second” with beads of sweat forming on my forehead kind of urge.

This didn’t happen once a month, oh no it didn’t happen once a week, this happened just about every single day. As soon as I got off the subway in North Philadelphia, I made a beeline straight for the bathroom. Because of this, I rarely had breakfast before coming to class. I was afraid it would only intensify how badly my stomach felt going to school.

107

Whether I liked it or not, getting back to a real-life routine was tough for me. It took extra effort and energy to do the little things. I still got out of breath going up and down the staircase. I was still as skinny as can be. But now, I had to try and balance the normal life of a student along with these challenges. Similar to the year before, I had days when I knew I needed to get assignments done or study for an upcoming exam but would be blind-sided by my health. The migraines I had been experiencing persisted for weeks on end. Oddly enough, those migraines came almost routinely on a Monday afternoon. Anything I had to get done from around four in the afternoon onward was tarnished by my ruthless migraines. Whatever I had for lunch that day was vomited up in the afternoon. Any schoolwork or time outside turned into sitting on the recliner with my eyes closed, hoping the pain would soon pass.

There was one day that I had a group project due the following day, so my group met as a team on Zoom. I was dealing with a migraine the past few hours so on the call I couldn’t concentrate on anything anyone was saying. I just shook my head “yes” and made trips to the bathroom to vomit after saying “Uh, I’l be right back.”

Sleeping at night turned into vomiting in the bathroom only to find myself crashing on the couch to save myself the extra couple of steps for the next time I had to run in. I showed up to each Tuesday morning class like a zombie. I didn’t sleep much and had little to no food in my stomach. Those migraines made it a tough fall semester. I couldn’t wait for the day that I could just show up to school and not have all those worries about my health holding up.

The migraines were a mystery to the medical team. I asked,

“Is it common to get migraines like this after transplant?”

“No, we haven't seen this before,” was the response from my nurse practitioner. “We should get an MRI to make sure there is no bleeding or anything going on.”

That immediately brought back terrible flashbacks from when I relapsed. Laying in a tight, congested MRI machine with my eyes closed hoping and praying that nothing bad came of it. Luckily, 108

the MRI revealed nothing abnormal. But, we still had no idea what the cause of my migraines was.

After suffering from two migraines in one week, we started to get desperate to find a solution.

At my last few doctor’s appointments, my blood pressure was running high. Especially for a guy who was only in his twenties. My nurse practitioner went with an aggressive approach and decided to discontinue my budesonide (which was already being tapered down) and started me on amlodipine which was a blood pressure medication. It definitely wasn’t a good feeling knowing I would be on a blood pressure medication in my twenties, but we had to try something. Both tacrolimus and budesonide could increase blood pressure. My opinion was that the combination of both of these could have been causing my migraines. To further support my rationale, the migraines started shortly after I began taking budesonide. We couldn’t get off of the tacrolimus just yet so removing the budesonide was the next best option. I just hoped the switch would pay off.

Being off steroids certainly had its benefits. Namely, I no longer experienced any more migraines. After suffering from a migraine almost weekly, it was incredible to not have to go through that anymore. When a Monday came around, I didn’t spend my evenings in a dark apartment pacing back and forth to the bathroom to vomit. I no longer felt like a zombie going to Tuesday morning classes.

On the contrary, being off steroids made my stomach begin to act up again. Those times when I felt like I needed to use the bathroom became the, “No, you need to go right now” trips once more which made my morning walk to school not so pleasant again.

The toughest part of being taken off the steroid was that I lost the energy the drug provided for me. Over the course of the past month, I did feel more energetic. I was able to wake up earlier and I felt more willing and able to put strain on my body by moving more frequently. But, when I stopped taking the medication, I felt that it suddenly disappeared. My walks were more strenuous. I didn’t want to get out of bed in the morning. I just wanted to lay on my couch whenever I could.

Was this how my energy level was going to be after my transplant for the rest of my life? I had waited months to get my energy back, only to realize what I thought was progress turned out to be side effects of a medication I was taking.

109

The third wall of my recovery was painful to get down. Just when I thought I was starting to gain momentum, another wrench was thrown my way. The non-stop trips to the bathroom. The migraines attacking every single week. The plummet in my energy levels when I was taken off budesonide. Each of these obstacles made me question my beliefs about making a full recovery. But when I really struggled, an old image kept surfacing in my mind.

It was me. My eyes were black and blue from puking the night before. I sat in the dark hospital room with the IV pole standing next to me. Tears were rolling down my face. Back then, life beyond those four walls felt unimaginable. So, if I was able to make it through that and still be here today, I had to be able to make it through the recovery.

When I am asked when I felt “back to normal again” after transplant, my reply today is, “When I chose to change my mindset on how I viewed my recovery by telling myself I had the power to get back to where I wanted to be.” In moments of self-doubt and disappointment, I had to remind myself of this: I was in control. As I mentioned previously, the first time I planted this seed in my mind was back around day 100 when I realized that day didn’t fix everything for me. I was so caught up in that end goal of being “normal.” What I missed was the most important part, the journey.

In many ways, I started my life from scratch after the transplant. Feeling comfortable walking, eating meals, growing hair back that I had lost, and finding purpose in each day. I envisioned what I used to look like prior to cancer treatment and kept comparing myself to that image. What I should have been doing was comparing myself to my own image on day 1 of transplant. I made progress during my recovery, but I never took time to acknowledge it and process how I made it come true.

I will always remember one day when I was up making myself breakfast. I had eggs cooking on the stovetop with bacon sizzling in the oven. On the counter I had a glass of water poured for myself with my plate, fork, and knife laid carefully. Months or even weeks before that day, I couldn’t have even imagined being strong enough to do all that myself. I was so blinded by my end goal that I wasn’t realizing those small victories in my recovery. Like Joanne and Sean reminded me while I was in the hospital focusing on my neutrophil levels hitting the right numbers to send me home, there is always 110

something worth celebrating over. We just need to step back to observe every once in a while. The problem is, we always fixate on the end goal. And as many of us have realized, once we hit that end goal, it doesn’t feel as good as we thought it would.

The true happiness lies in knocking down the walls before that. To conquer our self-doubt and our desire to stay complacent is the most rewarding experience of it all. It is essential that we reflect on these moments. There is a philosophy that pain + reflection = progress. Many of us want to progress, but never put ourselves through pain. Many of us feel pain, but never take time to reflect. By reflecting, we are able to pinpoint our catalysts in overcoming difficult situations.

What did I do well in that moment? How could I have been better? What am I most proud of doing in that moment? These are some questions we need to ask ourselves. Then, we may use those lessons to overcome future obstacles. Then, we may progress.

111

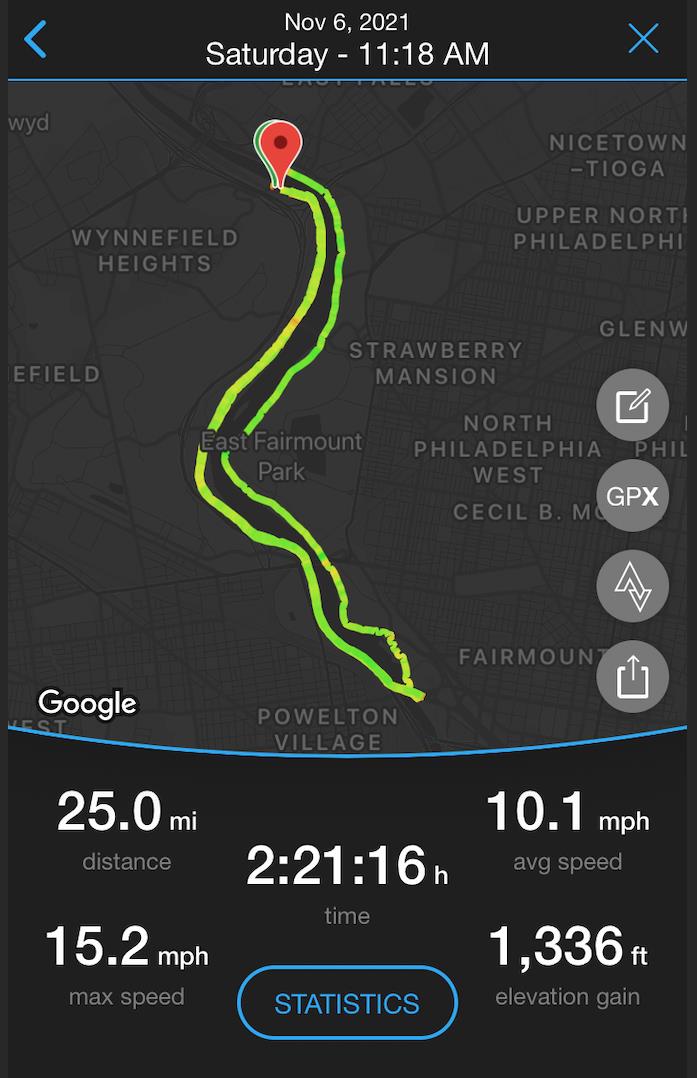

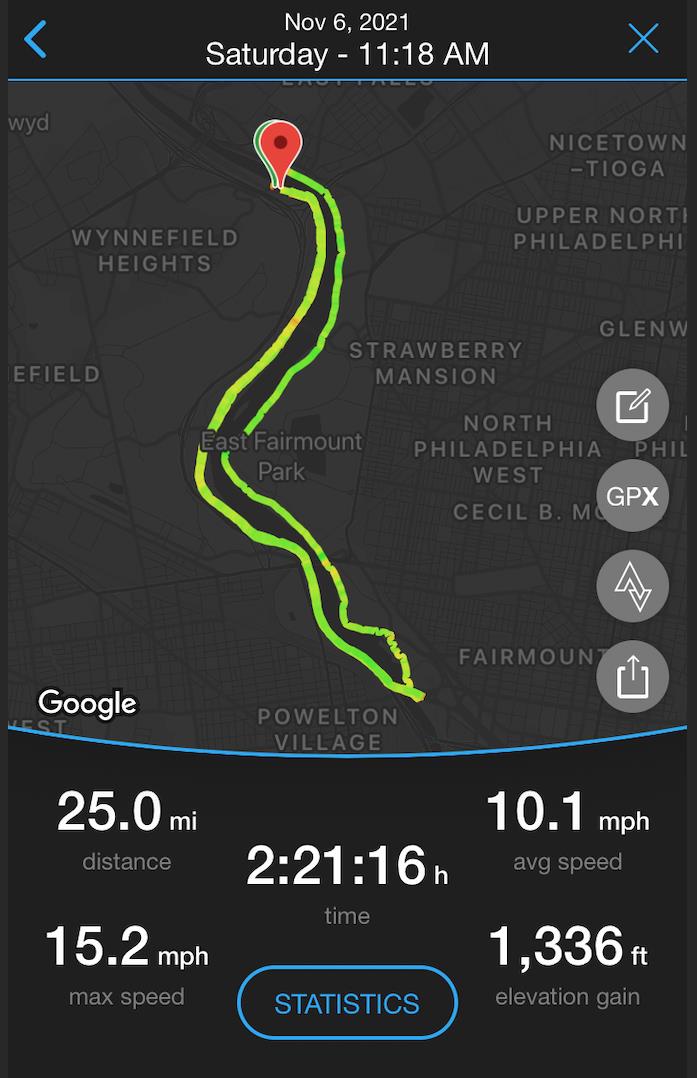

25.0

“Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.”

- William Ernest Henley

112

On my twenty-fourth birthday, I started writing down my goals. With the mindset of having to put in work to get where I wanted to be, it was time to start taking action. With months of contemplating everything you could possibly think of about life, I was ready to start living again. With that, I started making to-do lists for each day. It was a way to hold myself accountable and to map out the day. Taking my medicine and studying for exams were on my list almost every time. I made sure to include enjoyable moments too like walking around the neighborhood with Madison. Visually seeing what I had to get done on paper and checking it off was satisfying. For my future goals, I wrote them down on a sheet of paper which now is posted right next to my bedside (which still, to this day, is there). The purpose was to see them each day to be reminded of what I was working towards.

The road to recovery I traveled looked like a zig-zag line that rose and plummeted with no correlation. It was the most frustrating and rigorous path I have ever taken. But I was able to extrapolate those lessons I have learned and apply them to other facets of my life. The goals I wrote down on my list were ambitious but achievable.

I recently bought a bike at the time, which I thought would be a great way to test myself physically again. Madison and I went on rides together in the city. To start, we would do about three to four miles. I have to say, Madison would cook me on those rides. I tried as hard as I could to keep up, but I couldn’t hang with her. My legs looked like toothpicks pushing down on the bike pedals. That’s what losing all of your muscle and not being able to eat will do to you. I had to be patient with the journey. I would get my strength back, I just needed time.

113

After our rides in the city got easier, we ventured out to Wissahickon Park. It is a beautiful, wooded path just outside of the city. The challenge of this was that this trail actually had hills unlike the flat terrain of the city. Just as I thought I was getting the hang of this whole biking thing, I was humbled by the rolling hills of the trail. The whole trail was about five miles long. So, going to the end of the trail and back was just over ten miles. It took a few trips to the park for us to make it the whole length of the trail.

The first time we did the full ten miles, I remember telling Madison that she didn’t have to slow up to ride with me on the way back to the car. Before I knew it, I couldn’t see Madison anymore because she was already so far ahead of me. The gentle uphills were killer. A woman was doing a light jog right next to me on the hill and passed me with ease. At that point, my quads were as sore as could be.

Then, a young guy passed me on his bike that looked to be around the same age as me. The voice inside my head started talking to me. “That is what you are supposed to look like. But you aren’t there yet. You have to earn that.”

I pushed through the remainder of the trail chasing after that “healthy version” of myself. I tested my fragile body to the limit. Once I made it back to the car, I remember resting my bike on the ground and feeling sick to my stomach. I asked Madison if she could drive us back home. That’s how you know I real y felt beat. Despite how poorly I felt in the moment, there was a sense of pride in myself. “I could do more next time,” I told myself. When I returned home, I wrote down on my list of goals, “I will bike twenty-five miles.” And there, the chal enge began.

This was around the time of year when I started reflecting back on the challenges I had faced through the transplant process. Through reflection of my hospital transplant stay, I pondered over the words that were said to me, “It’s just four walls.” This is where the metaphor was born, through reflection. Whether I knew it or not, I was breaking down those walls to make it out of the hospital and back home. Accepting the challenge. Realizing it will be difficult and I will feel uncomfortable. Feeling like I want to quit and that winning isn’t an option. Feeling motivated only to feel that urge to quit not long after. Until, finally, the finish line is just ahead. And the fourth wall comes crashing down.

114

I worked my way up to biking fourteen miles on my own. I was able to complete just over half of my goal of twenty-five miles. Then I built up to a sixteen-mile ride. My legs were becoming stronger.

The weather was starting to get cold too. It was early November and the cool fall breeze made biking not as enjoyable as it once was in the late summer. There was an upcoming Saturday with a high temperature of fifty-six degrees Fahrenheit. I circled that day in my head and said, “That’s the day.”

I woke up that Saturday, had a small breakfast, then Madison and I drove over to MLK Drive.

There was a nice bike loop in that area. One side of the river had a thin trail with plenty of runners, bikers, and walkers. On the other side of the river was a multi-lane road that was closed to motor vehicles on the weekend making it the perfect place for a bike ride. I accepted the challenge and hopped on my bike for my attempt at the twenty-five-mile ride. I said to myself, “Remember, it’s just four walls. I’ve been through this before.”

First, I crossed the bridge over towards the more crowded side of the river. Initially I would have liked to do as many loops around the river as necessary to reach twenty-five miles but quickly realized I was much better off staying over on the less crowded side. Despite the previous rides I had done with fourteen and sixteen miles, I felt fatigued by mile six. I thought to myself, “What is going on with me today?” “How am I already hitting the second wall?” Like I had anticipated, I was already making up excuses for why I failed this attempt.

“I didn’t eat enough this morning. That must be why.”

“I just want to grab some lunch. I can try again another day.”

“Instead of doing twenty-five miles, maybe I can just do twelve and a half.”

It was human nature kicking in. I felt the need for comfort. The fear of failing crept into my mind.

The excuses continued to consume me. “You just had stem cell transplant a few months ago! It’s too soon for you to try something like this.”

I shouted in my head, “Just don’t quit on me!” Now was the chance to final y prove to myself that I can put all this cancer nonsense behind me. To show myself that regardless of everything I went through, I would still come out stronger. All the nights I had crying myself to sleep were burned into my 115

memory. Again, I pictured myself laying in the hospital bed. I sat with the look of defeat in my eyes.

That same face began to laugh at me. “You went through all this, just to sell yourself short? Have you learned anything from this? Stop feeling sorry for yourself and pedal.”

I overcame that first itch of quitting, and I edged closer to the midway point of the ride. My back ached. My legs started to feel like the jello I was fed in the hospital all of those months. “Just keep pedaling,” I repeated over and over. “Stay focused. Don’t be a prisoner to your emotions. Don’t let your thoughts continually remind you how your back and legs are feeling.”

I tried every trick in the book to prevent myself from quitting. But, yet again, I couldn’t help to think, “Maybe I should just call it at eighteen miles.”

“I really feel like stopping to have some lunch soon.”

There’s a beautiful quote I once heard that resonates with this feeling. “We give up what we want most, for what we want now.” I wanted to finish that ride more than anything. It would be a breakthrough moment for me both mentally and physically. Despite how badly I knew I wanted it, my mind wanted to quit. And it wanted to quit now.

Remind yourself who is in control. Don’t give in to the “sweet talk” your mind tries to ease you into. In these moments, listen to what goes on up there. I mean really listen. Take notes. I noticed that when faced with a challenge, the voice in my head increased in both frequency and intensity. You will never be able to completely suppress them, but you can learn to tame them.

During the bike ride, it felt like my mind was screaming at me every five seconds. “Stop! You aren’t strong enough to do this. Just call it quits already.” From the technique I learned during my transplant stay, I focused on what I could control. I focused on what the most important tools were to help me finish the ride. “Just keep pedaling. Don’t let those thoughts take over. Focus on your breathing and keep moving those legs.”

Each mile became more demanding. No matter what type of cushion you put on a bike seat, eventually, it feels quite uncomfortable. Madison sat off the side of the trail on one of the benches. I waved to her each time I passed. From one end of the path to the other was only about two miles. It 116

got old very quick riding back and forth on the same road. But being able to see Madison each lap was the highlight of my ride.

As I now approached mile twenty, the voice inside my head flipped the switch. Instead of my mind trying to persuade me to quit, it suddenly started saying, “There is no way you can stop now.”

That’s how I knew I knocked down the third wall. Now, it was time to finish the job. I was in control of the outcome. Not the voice inside my head that had been telling me to quit.

Down and back. That is all I had to do to wrap up my twenty-five-mile bike ride. As I rode on my second to last lap, tears filled my eyes. I never thought I would make it to that point again. I had hit what felt like rock bottom multiple times over the past year and a half. Looking back, the climb back from those moments was such a beautiful experience. Of course, I was blind to that idea during the time. But each day, I was slowly growing as a person. I had to adjust my life in so many ways, but I still managed to get by.

The tears rolled down my face on my last few miles. My diagnosis, the pain from my first bone marrow biopsy, the hematomas in my arm and leg, being told about my relapse and breaking the news to my family, sitting alone in the hospital and thinking about hurting myself to escape to that terrible life, puking so frequently that my eyes turned black and blue during my transplant stay, losing forty pounds twice. All of those moments that tried to bring me down. Yet, there I was, about to bike twenty-five miles.

Just under two miles to go. Madison biked alongside me as I struggled to make it to the finish line. Every part of my body felt sore. I desperately needed to rest. I put my head down and pushed down on the pedals as hard as I could. I didn’t want to look up and see how slow I was moving at that point. I stood up on my pedals every other minute to give my legs a breather.

I rounded the corner and faced the worst part of the lap. The final uphill straightaway. I could have screamed because of how bad my legs hurt. “Keep pedaling! You are so damn close. Finish strong!”

117

I reached the top of the hill, hopped off my bike, and let it slam to the ground. My legs barely held my own weight as I tried to stand tall. I looked at the GPS on my phone, and there it was: 25.0

miles. What an amazing feeling it was to hug Madison after seeing that. It was that moment that revolutionized my strategy for attacking life’s chal enges. Just as I had broken out of the four walls that tortured me in the hospital, I now had to break down the four walls that I kept myself in with each goal for the rest of my life. That day symbolized what I considered to be “the end” of my recovery. I now understood that the strength inside of me was always there. I just had to be willing to search deep down to get it.

118

Just a month after that bike ride, I was finally able to get the PICC line removed from my arm.

That meant I was able to start lifting weights again. That hobby was essential for me to “feel like me”

again. After almost two full years without lifting weights, my body was puny. From being able to squat well over two hundred pounds before cancer treatment, suddenly, forty-five pounds on my shoulders felt like plenty. It was a total reset from a fitness point of view. From what I had learned during the transplant journey, I did not fixate on how I used to look or how strong I used to be. Now, my goal was to enjoy the journey of getting back to a strong and healthy version of myself, no matter what that may actually look like.

I experienced a full-circle moment during the spring of that year. On Fridays, a group of friends and I got together to play basketball. It felt amazing beyond words to be out and active again. On one particular Friday, we pulled up with our usual group. There were a few others already shooting around so we set up three teams of four to run games of four with one team sitting out. One of the guys looked oddly familiar. I thought it may have been a certain someone who worked at the hospital, but I couldn’t tell because he was no longer wearing a mask in front of me. Before we started our first game, we introduced ourselves to those we didn’t know that were on our team so we knew everyone’s name.

“What's up man, I’m Ryan,” I said to him.

He replied with, “Sean.”

Wait a minute… No way. There’s no way that’s the same Sean that took care of me in the hospital. But wait, it has to be. I knew he looked familiar, and he did say that he lived close to me in 119

the city while I was in the hospital. I wondered if he would be able to recognize me now that I had hair on both my head and my face. Ah well, let’s play this game and I wil ask him after.

Throughout that game, all I thought about was how that might have been Sean. After we played, I got a drink of water, and I approached him.

“You said your name was Sean, right?”

He just started laughing. “Yep.”

“Do you happen to work at Penn by chance?”

“Yeah, that’s me,” he replied as he continued to laugh.

We immediately hugged right after.

What are the odds I would run into one of the best people to take care of me almost a year after being in the hospital? That moment with Sean on the basketball court was one of the most heartwarming experiences I have ever experienced. I was able to thank him for all that he did for me.

Almost a year ago, he was giving me medicine and nutrition around the clock to keep me functional.

Now, I was out playing basketball with him. Life always has a way to reconnect you with the people you are supposed to see, and I am so glad I ran into Sean again that day. I hope he was able to see the impact his job has played in my life by transforming my health in the past year. Because of many great people like Sean, I am blessed to feel healthy once again.

120

Friendship, Love, Family

No matter if we live until we are one hundred years old or twenty years old, we never really get enough time with those we love most, do we? We may never know when our last moment will be with the people we love. Everyone always says to one another, “I wil see you soon.” Maybe you wil , and that’s great. But what if you don’t? What if it is months or years until you see your friends and family again? Or you may never see them again at all.

Knowing that our time is limited with one another should stress the importance of expressing our love. We never want to imagine what it would be like to lose people we are close to in our life. From my experience, I had to imagine that. I was forced to imagine it far too many times. I knew what I was going through was dangerous and perhaps even deadly. I was blessed with an outstanding number of people to help me every step of the way. A network of people giving their support to cheer me on to the finish line. I will always remember one of the beautiful messages that I received when I was first diagnosed with cancer. It read, “I hope one of the things you can take away from this is truly how many people care about you.”

Truthfully, I was blown away by the support I received. I couldn’t have asked for anything more. “We are only as strong as we are united, as weak as we are divided,” said J.K. Rowling. The power of friendship, love, and family played a tremendous role in my ability to make it through two battles with cancer.

121

Friendship

When I was first diagnosed, I received a plethora of text messages from my friends. I cried reading each and every one. As I laid in my bed fearing for my life, my friends were able to give me hope. Seeing the names of my friends from childhood, high school, and college all pop up on my phone sending words of encouragement reminded me that I wasn’t alone in my fight. One lesson I learned from my experience is to not wait to express your love for your friends for a scary moment. Express that love for them whenever you can. For guys especially, we don’t express ourselves to one another as much as we should. Make sure you know what is going on in your friends' lives.

“What has so and so been up to?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Nothing is new with him. He is just workin’.”

“What does he do for work?”

“No idea. I think something in business.”

Far too often, we get caught up in our own lives and forget to check in on those that are important to us. Blocking off just fifteen minutes in your day to call a friend could go a long way. Not calling to ask anything of your friend, just calling to say, “Hey man, I was thinking about you.”

Each friend of mine handled my diagnosis differently. When I was around some friends in person, they acted like nothing ever happened. We laughed and joked like we always would. Others seemed more reserved. They always asked about how everything was going, how I was feeling, what the doctors had been saying, and what steps would come next. I appreciated both approaches for their own reasons. Some days I wanted to forget this had ever happened to me. I wanted to live life like I 122

was “normal” again. Those days felt amazing to be around my friends that stil loved to laugh and joke with me. Other days, I just needed someone to talk to and let out some emotion. Those days it felt relieving to be around my friends who asked those types of questions.

Socially, I felt out of place. I went from conversations solely about my health with my family and healthcare team to conversations about anything and everything with my friends. Especially due to COVID, I was far removed from many social settings. Truthfully, I almost forgot how to act in public.

Most activities that people my age would do like going out to eat, hanging out to watch a sporting event, or going out to a bar were a few things I have not done for months or even years at that point. It absolutely changed how I choose to spend time with my friends today.

Like most people in their twenties, I used to think drinking at the bar was a great time with friends. After being removed from that setting for years, I have realized how it was unnecessary in my own life. I am not knocking that lifestyle at all. I am just no longer a part of that crowd. I enjoy quality time with my friends and being able to have meaningful conversations. So many times, we choose places that aren't possible to have those talks. Being surrounded by many other people with music blaring in my ears wasn’t fun for me anymore. Enjoying dinner together and having conversations with one another is now what I cherish most with my friends.

Most people my age will never experience what I had to go through, thankfully. And I understand that. All I want to do is share my perspective that may open up the eyes to some of my friends, and perhaps friends of others. I have no idea what life has in store for me tomorrow. And you that are reading this book, neither do you. The unfortunate truth is that cancer could come back any day now and remove me from the life I live today. Even if I wanted to sit down and catch up with some of the friends that I love so dearly, I wouldn’t be able to. The friends I haven’t kept in touch with for months may not even hear the bad news. Remembering that is a real-life scenario for me that makes me want to reach out to all of those people that are close to me whenever I could. It makes me want to be a better friend and not be afraid to say the, “I love you because” even though I may see that friend next week.

123

Out of fear of missing someone from this book, I tried to avoid using specific names of my friends throughout. It’s not that I don’t want everyone to know how supportive and loving they have been towards myself and my family. I was blessed with so many lifelong friends that I could write for days about all of the moments that stood out to me from them.

The phone calls while I walked the halls in the hospital and the texts of encouragement. The friends that visited me while I was in the hospital. The friends that came to visit me behind my house because I was too afraid to be around others while indoors. The video message I received when I was first diagnosed. The phone call to check in with me when I first relapsed to see how I was holding up.

The friends that surprised me when I first finished treatment and was able to be around others again.

The friends that came together to surprise me for my one-year post-transplant milestone. The friends that came together to celebrate my second-year post-transplant milestone. The pictures, the videos, and the memories all shared with me to cheer me up during tough moments. Giving Madison and my mom rides to and from the hospital to visit me. Allowing my mom and Madison to stay with a friend to remain close by for those visits. Raising money for my family and I to pay for healthcare expenses.

Receiving beautiful cards from many friendships made at home, school, and work over the years. So many unbelievable moments from the best friends I could ever ask for.

124

Love

Almost a year and a half post-transplant, there was a stretch of days during the summer of 2022

that scared me to death. The weather was starting to get hot as I traveled up to campus each day for my rotation. I wore my dress shirt and tie which didn’t fare well with the heat. I started to sweat through the back of my shirt, so I hung my bookbag over my right shoulder when I traveled outside. One Sunday morning before I went in for a work shift, I looked down at my right shoulder in the bathroom. There was a petechiae-like mark right where I normally carried my book bag. “Here we go again,” I thought.

“Why does this have to keep happening to me? Can’t I just enjoy my life for a little bit? No, it can’t be.

It is just a mark from my bookbag.”

I still went to work that day. I kept my mouth shut and chose not to speak much. No matter what I did that day, I thought about how I might have relapsed from cancer yet again. I couldn’t think about anything else. I had no idea how I was going to break this to Madison. I walked to the back of the pharmacy many times that day to look at my shoulder hoping the mark would fade by the time I got home. Each time I looked, it looked like it grew darker. It slowly ate away at my mind, and I couldn’t wait to get answers. Al I wanted was to get bloodwork done to make sure this wasn’t happening again.

My shift at work finally ended and I went back home.

It warms my heart how Madison greets me when I walk in the door. She always makes me feel so special and loved, no matter what day it was. Having her greet me on that day made it hurt so much more. I went to the bathroom one last time to see if the mark was stil there… and of course it was. I stepped out and said, “I don’t want you to freak out, but I saw this on my shoulder this morning.” As I 125

took off my shirt and pointed to my shoulder, I saw the excitement in her face fade away. We didn’t know what it was yet, so we didn’t want to jump to any conclusions.

All I remember was sitting down on the couch and beginning to cry. Madison went and knelt behind the kitchen cabinets because she didn’t want me to see her tears. She stood back up and came over to me and we hugged so tightly. We shed so many tears together that day. It wasn’t the cancer that I cried about. It was the thought of leaving this world without Madison that truly broke my heart.

Long story short, those marks on my shoulder were actually from the bookbag and nothing else.

It was an evil reminder that I should be grateful for the life that I now have. It also served as a reminder that the woman I love so dearly, our time on this Earth together is limited too. More than ever, I reflected on everything she has done for me throughout treatment. The strength and maturity that she possesses is undeniable. I know many people like to comment on how strong they thought I was during my treatment. But it is time for you all to hear about the real hero of the story, Madison.

Neither of us knew how to handle the news when it first broke from my diagnosis. We were both barely young adults at the time when we were about to move in with one another. Madison gave me one last hug before I was carted away onto the ambulance to get transferred to Philadelphia. From that moment forward, I admired the strength she was able to wear on her face, especially when I wasn’t able to. Energy can be infectious, and she always infected me with her positivity and optimism even during my worst moments.

Madison came to visit me during my initial hospital admission many times. There was a day in particular that stood out to me. After my lumbar puncture when I began to feel sick, she visited me shortly after. While I sat in my bed puking into a bucket for hours, she sat right next to me through it all. I didn’t have the energy in me to even speak to her, yet she sat quietly and patiently waited in case there was something I needed. I drifted into an hour nap. When I woke up, she still sat there next to me. She too had fallen asleep but with her hand resting on top of mine. It was small acts like those that had such a major impact in my recovery. As my mom had always joked with the hospital staff, Madison was truly my best medicine.

126

I had issues believing in my abilities throughout the process. I often felt discouraged and lost hope. As I walked the hospital halls with my feet dragging beneath me, I stared down at the colored tiles. I feared that at any minute I could easily pass out with how lightheaded I felt. “You could do it. Go as slow as you need to,” she would say to me. She pushed the IV pole for me and held onto my arm.

She quite literally held me up when I felt like falling down.

I am most proud of the growth Madison and I had together throughout our experiences. We approached every challenge as a team. It was never a “me vs you” mentality. For me, I lost sight of that mindset a few times. But she never did.

In the middle of the night when I broke out with a neutropenic fever, I was so mad she called the doctors to let them know. I got mad at her for doing the right thing! What an unbelievable thing for me to say. She knew how much I hated going into the hospital, and letting the doctors know would sign me for just that. I was a baby about it. I complained how I would be just fine, even though we both knew how serious a neutropenic fever could be. After one last complaint to Madison on the way to the hospital, she pulled over on the side of the road. Past midnight and in the middle of the pouring rain, she pulled over to remind me of our team concept.

She always knew the right thing to do and did it regardless of how either of us felt about it. That is one of the many ways she was able to show her true love for me. Doing the right thing despite how it made her feel. I’m sure she did not want to wake up in the middle of the night, go get the car in the pouring rain, and drive me over to the hospital. But she did it anyway. Not just for me, but for us.

And so, we went to that emergency room that night. I got the appropriate treatment I needed, and everything went okay. In a strange way, I felt at home with her that night in the emergency room.

Even with the glass door in front of me, bright lights, and constant buzzing out in the hal s. That’s when I realized home wasn’t a place. Home was being with the people you love. Whenever she was with me, I was home. Had I been alone, I would have succumbed to the stressful and chaotic environment I was placed in. Instead, we sat in that uncomfortable little room while laughing and smiling with one another.

127

My recovery from transplant was a stressful time not just for me, but for those around me as wel . It was taxing on both the mind and body. My attitude wasn’t helping either. There was a lot that had to be done for me. Feeling weak on my own legs, taking over twenty pills a day, and creeping my way towards malnourishment as the days went on because of my lack of appetite. Madison worked a full-time job remotely at the time. She organized all of my medications for me in a pill container. She prepared my magnesium infusions for me after my transplant. She flushed the lines of my PICC each day. I didn’t have to raise a single finger to set any of that up for myself.

When I was feeling too sorry for myself to even get myself a glass of water, she came right out to do that for me. She prepared every meal for me. I know how daunting that was for her. My stomach couldn’t tolerate much so I was extremely picky with my meals. Regardless, she always made sure I was eating as much as I could when I could. She did everything in her power to make sure I was getting the calories I needed to regain my strength.

Our daily walks are a staple of our day I will cherish forever. We would take in the incredible neighborhood we were blessed to live in together every single day. I always said to Madison that we have our best conversations on our walks. There are no phones out and no distractions. It was just us soaking in the fresh air. Even though our walks were few and far between what we could do now, we made the best of our time together. Walks that could have been a mile long turned into one to two city blocks long. My calves cramped up constantly. The summer heat irritated my sensitive skin. The warmth of the sun caused the painful “zaps” all throughout my body.