153

Stage Three – Evaluation/Re-evaluation (re-authoring)

To bridge the learning gaps that have been identified in Stage two, the coach continues to focus on those thin story lines that could strengthen the coachee’s sense of identity; gather more evidence to support the alternative storyline (thicken the plot).

This stage provides „scaffolding‟ to bridge the coachee’s learning gap by recruiting their lived experience. The coach asks the coachee to re-evaluate the impact of their action upon their own sense of self-identity, values and belief, stretch their imagination and exercise their meaning-making resources.

The coach also encourages the coachee to map their aspirations, values and self-identity upon their action in terms of new future possibilities on their life’s horizons. This stage is very often referred to as „the turning point‟ where the coachee begins to change from re-iterating the old story line to start discovering new possibilities and action.

Stage Four - Justification

The coach further thickens the plot of the story and consolidates the coachee’s commitment for change. The aim of narrative coaching is to develop a „thick description‟ of an alternative storyline “that is inscribed with…meanings" and finds linkages between "the stories of people's lives and their cherished values, beliefs, purposes, desires, commitments, and so on"

(White, 1997, p.15-16).

At this stage, the coachees are asked to justify the above evaluation in terms of their aspiration, belief, values and self-identity and strengths.

154

Stage Five - Conclusion/Recommendation

The coach guides the coachee to draw conclusion by making valued statements about their self-identity in terms of their beliefs, values, hopes, and dreams. The coach may ask the coachee to write these statements down in words on a piece of paper or in a form of letter, etc. Finally, the coach invites the coachee to make commitments for action by summarizing an action plan for change and how to achieve their hopes and dreams (the „bridging tasks‟).

155

2.6.2 Practical Narrative Approach to Coaching The narrative approach to coaching investigates the stories that people construct in their lives to define who they are and what they do. It is the coach’s role to help coachees identify stories that are limiting them from achieving their full potential and to assist in finding an alternative story that is more beneficial.

The coach has four main aims when implementing the narrative approach:

1. Search for alternative explanations

2. Search for unique outcomes

3. Encourage a future with the alternative story 4. Find ways to create an audience who will perceive and support the new story.

Let us look at some of the main concepts of this approach: Dominant Stories

Dominant stories are stories in a person’s life which he or she strongly believe and have had things happen in life that have reinforced this story. They can have both positive and negative affects on the individual’s life and affect not only the present but also the future.

Stories consist of the following elements (De Jong & Berg, 2002):

Events

Linked in sequence

Across time

According to a plot

156

For example:

John is a successful executive to an important financial company. However, he lacks confidence in his typing ability due to situations that have occurred in the past. For example, when he was in high school he completed a typing course in which he failed. In his first job as an administrative assistant he was always in trouble for taking too long to complete projects and he thought this was due to his typing “inability”. Now that he has his own administrative assistant he gets him to type everything for him but is finding that other tasks are not completed due to this problem.

John’s dominant story of not being able to type has been reinforced by past incidences of being told he can’t type and failing a typing course. He now reinforces this issue by getting someone else to do the typing for him. Although John’s story is quite basic, you can see how this dominant story affects his present and will also keep affecting his future.

Externalising Language

Externalising language is used in coaching to separate the problem from the person. For example, a person may say “I am a sad person”. This implies that the person has a sad quality or characteristic of sadness rather than it just being something that affects the person from time to time.

Coaches working from a narrative perspective are attuned to the language they use to represent an issue or problem in their coachees’ lives. They assume that the issue or problem is

“having an effect on the person” rather than the issue or problem being an intrinsic part of who the person is.

Rather than saying “you are lacking in motivation”, a coach working from a narrative perspective may ask “when did motivation leave you?” OR rather than say, “you are stressed” 157

the coach may enquire, “when did stress get a hold of you?” Unique outcomes

Unique outcomes are situations or events that do not fit with the problem-saturated story. When searching for unique outcomes, coaches focus their attention on finding any event or experience that stands apart from the problem story – even if the situation appears to be inconsequential to the coachee.

Example transcript:

In this example, Ben is in year 12 and is aiming to achieve a scholarship for university. Ben doesn’t usually have a problem with motivation, but lately he just can’t seem to find the energy to study. With assistance from his counsellor, Ben has named his lack of motivation, “the energy-zapper”.

Here is part of the conversation that takes place between Ben and his coach:

Coach - When did the energy-zapper first make an appearance in your life?

--Ben - Hmm, well I think I first noticed him in grade 9. I went through this stage where he was turning up and zapping my energy all the time!

Coach - Was there ever a time when you were able to overcome the energy-zapper’s powers?

--Ben - Umm… yeah, once I was so behind in Maths that I just knew I had to study otherwise I would fail the next exam.

Coach - So what did you do?

--Ben - Well, I guess, I just focused. I turned off the TV - I knew I had to turn off the TV - Then I thought, right I have to do this. I just have to.

158

Coach - And did you do it?

--Ben - Yeah, you know, I did…and it really wasn’t that hard to stay focused once I got into it. I stayed up all night to study for that exam.

Coach - So the energy-zapper loses his power when you really focus your attention on something.

--Ben - Yeah, I guess he does (laughs).

This conversation reveals a unique outcome for Ben.

Techniques

Techniques that will be examined in this article are: 1. Naming the problem

2. Asking externalising questions

Naming the problem is used as a way to establish a sense of distance from, and control over the problem. This is a main aim of the narrative approach.

Payne (2006) has identified a number of questions you may wish to use to help the coachee name the problem:

“I wonder what we will call this problem?

Do you have a particular name for what you’re going through at the moment?

There are lots of things happening to you- shall we try to pin them down? What are they, what name shall we put to them?

I’ve been calling what they did to you ‘constructive dismissal’.

Does that seem the right term to use?

Judging by what you say, you’re been subject to emotional abuse. How would it feel if that’s what we called it from now on?

Or perhaps there’s a better name?”

If the coachee has trouble coming up with a name, you could suggest possibilities.

159

For example:

Sam is a 25-year-old professional, who has recently been promoted to a business development position within her organisation. As part of this new role, Sam will be required to provide product information to a large number of potential customers in a conference style presentation. Sam considers herself to be ‘nervous by nature’ and is worried that she may find this aspect of the role intimidating.

Sam and her coach have named her nervousness, the intimidator.

Externalising the Interview

Externalising questions and statements involve referring to the problem as being external to the person. For example, “you are shy” compared to a narrative approach of “when did shyness get a hold of you?” Other examples of making externalising questions include:

How does the (problem) interfere in your life?

How does the (problem) manage to take control of you?

When does the (problem) usually strike?

Have you noticed in anything makes the (problem) stronger?

How is the (problem) hold you back?

Here’s an example from an interview with Sam (playing the role of the intimidator):

Coach – Intimidator, when did you first start spending time with Sam?

-- Sam – (As the intimidator) Gee, I started hanging out with Sam when she was young about 4, maybe 5 years old.

Coach – Wow, you’ve been in Sam’s life for a long time. What has made you stay so long?

160

-- Sam – (As the intimidator) Ha, ha. Well, I get a lot of opportunities to wield my powers. Sam’s easily led; I can overpower her without any difficulty.

Coach – Really? When is she at her most vulnerable?

-- Sam – (As the intimidator) She’s definitely her most vulnerable when she is unprepared. It’s so easy to overpower her then.

Copyright © 2010 Mental Health Academy

Source: www.mentalhealthacademy.com.au

161

2.7 THE GATHER FAME MODEL

The GATHER FAME model is a very practical model, which consists of two parts : “GATHER” refers to the actual coaching process, which, however, is not complete without the second part : “FAME”, being the follow up.

In “GATHER”, G is for Greet:

- Greet the coachee: introduce yourself, offer a seat, and create a warm but professional environment.

- Ask how you can help.

- Assure coachee of confidentiality.

A is for Ask:

- Ask about their reasons for coming now.

- Help coachees tell their story, express their needs and wants, doubts, concerns, questions and problems.

- Ask about previous experiences

- Ask what they want to do

- Show interest, understanding and empathy

- Reflect, support, ask open questions to encourage communication,

- Avoid judgments and opinions

T is for Tell:

- To make informed choices and good decisions, coaches need clear, accurate, specific information about the range of their choices.

- Give tailored information: tell what is relevant and important to the coachee’s decision.

- Give personalized information: always start from coachee’s specific and unique situation and take it into account in all you say.

162

H is for Help:

- Help coachee think about positive and negative results for him personally of each selected option

- Help them think how they would feel about these results.

- Help them prioritize: which options are more important and urgent?

- Ask what other important persons in their life might want.

- Clarify, repeat and reword information when useful

- Remind coaches that the choice is theirs to take. Avoid making decisions for them.

- Check whether they have made a clear decision. Ask: “So, what have you decided to do?” and wait for them to answer.

E is for Explain:

- Explain how to carry out the decision

- Help coachees think how to adopt new behaviour.

- Explain what, when, how, where …

- Show how, hand printed material to take home

- Ask coachee to repeat instructions, to tell you how they will implement their decision

- Help them rehearse planned conversations, interviews, presentations, ….

R is for Return:

- Ask coaches if they have any questions or subjects to discuss (1)

- Ask them if they are satisfied with the outcome (2)

- Help them handle any problems (3)

- Plan follow-up and evaluation

163

In “FAME”, F is for Follow-up

- At the follow-up meeting, repeat points 1,2 and 3 from the Return-phase

- Ask if anything changed since the last meeting

- Ask them to think about their decision again and to confirm it, or to adapt it if they wish … or to make a new choice

- Check if coachee is living up to their commitment. Can you help them in any way?

A is for Apply Coaching Techniques

M is for Monitor Progress:

E is for Evaluate / Wrap up

- What is the concrete result?

- Any further questions?

- Assistance or additional resources required?

- End Coaching relationship, but keep door opened.

164

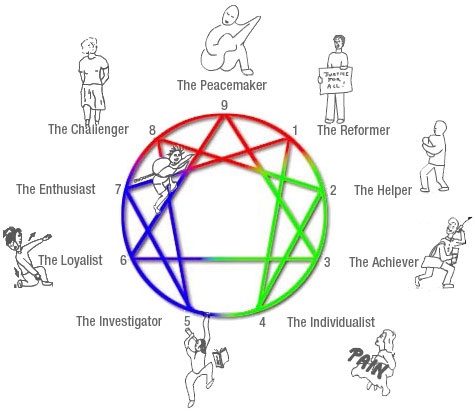

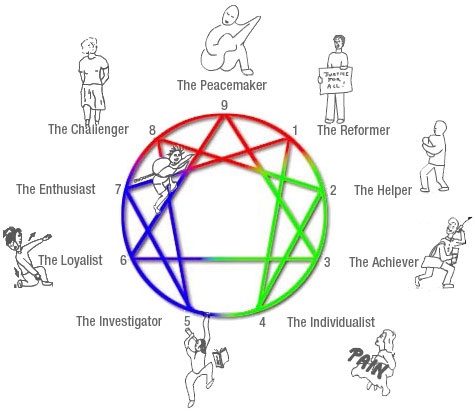

2.8 ENNEAGRAM BASED COACHING

History

The Enneagram is an ancient system – at least 2000 - 4000

year’s old. The word comes from two Greek words ennea (“nine”) and gram ("something written or drawn”), and refers to the nine points on the Enneagram symbol. The nine different Enneagram styles, identified as numbers One through Nine, reflect distinct habits of thinking, feeling, and behaving, with each style connected to a unique path of development.

Each person has only one core Enneagram style, and while our Enneagram style remains the same throughout our lifetime, the 165

characteristics of our style may either soften or become more pronounced as we grow and develop. In addition to our core Enneagram style, there are four other styles that provide additional qualities to our personalities; these are called wings and arrows.

Current Usage

More than a personality typology, the Enneagram is a profound map illuminating the nine different architectures of the human character. It is also the most powerful and practical system available for increasing emotional intelligence, with insights that can be used for personal and professional development.

Because the Enneagram is cross-cultural and uncannily accurate, it’s modern usage is growing dramatically across the globe.

In addition to being used by individuals who embrace it for their own insight and development, organizations are using the Enneagram to increase emotional intelligence (EQ), enhance communication, manage conflict constructively, build high-performing teams, develop leadership, and more.

Enneagram Coaching

1. Working on Yourself

The Enneagram is about movement and change, letting go of fixed identity and opening up to the possibility of transformation. G.I. Gurdjieff, the teacher who first brought knowledge of the Enneagram to the West, taught that we have two natures – ‘Personality’ which is essentially illusory, an image of ourselves that we learn from others; and ‘Essence’, our true nature. The Enneagram type belongs to ‘Personality’ in this specialized sense – and is therefore false, something we are unnaturally attached to through conditioning. The aim of 166

Gurdjieff’s system was to help people let go of this false self-image so that their true Essence could emerge.

So the point of identifying your Enneagram type is not to put you in a box or stick a label on you - but to show you where the type (your self-image) helps you and where it is getting in your way. By deliberately working ‘against’ your type, you can open up new perspectives and make changes in long-established habits.

Enneagram teachers typically recommend two ways of working on yourself with the Enneagram.

The first is simply to observe your type - read the descriptions and notice when you find yourself compelled to act according to type. For example - if you are at point Two, notice when you feel compelled to help someone; if you are at point Seven, notice when you get bored and feel the need to lighten the mood; if you are point Five, notice when you feel the need to withdraw from the group and gather your thoughts.

Getting into the habit of ‘just observing’ yourself is a great way to learn about yourself, even if the observations can make uncomfortable viewing at times. One Enneagram teacher, Richard Rohr, says we haven’t really ‘got’ the Enneagram until we have been humiliated - meaning that it is a humbling experience to realise how much of our thoughts, feelings and behaviour are conditioned by our type. On the other hand, this can also help us to develop compassion for ourselves – and for others, when we notice that they are also trapped by their type.

If you’re feeling really brave, you might want to show the description of your type to a trusted friend and ask them whether they think it’s accurate - pick your friend wisely, and be prepared for a few home truths!

167

Let’s have another look at the Enneagram symbol: Notice the arrows that have been drawn on the diagram - these indicate the ‘path of least resistance’ in the face of the difficulties of life. So for a point One Reformer, the path of least resistance leads to point Four - whenever he is overwhelmed by the difficulties of achieving his goals, he is tempted to retreat to Four and take on the less desirable qualities of that type, by getting depressed and lamenting the state of the world.

If he moves in the other direction however, against the direction of the arrows, then he arrives at point Seven, which is when he lighten up and starts to embrace the positive side of life.

Challenges for each type

Each Enneagram type faces a similar challenge in moving

‘against the arrows’ in order to overcome the limitations of their type:

168

• Point Two - can you move to point Four and focus on your own needs as well as others’?

• Point Three - can you move to point Six and spend time out of the limelight as a member of the group?

• Point Four - can you move to point One and adopt a more objective critical perspective on your own feelings and dreams?

• Point Five - can you move to point Eight and put yourself on the line by applying your knowledge in the world of action?

• Point Six - can you move to point Nine and set aside your suspicion by trusting others and celebrating difference?

• Point Seven - can you move to point Five and stop being a butterfly by focusing on one option and seeing it through to completion?

• Point Eight - can you move to point Two and set aside your own love of power by using your strength to serve others?

• Point Nine - can you move to point Three and allow the spotlight to rest on you as you perform at your best?

• Point One - can you move to point Seven and let go of your drive to achievement long enough to enjoy the pleasures of the moment?

Questions

• Has there ever been a time when you’ve caught yourself

‘responding from type’ and been surprised at how easy it was to get carried away by automatic thoughts and actions?

• Has there ever been a time when you’ve gone ‘against your type’ – either deliberately or because the situation demanded it

– and discovered how liberating it can be?

169

2. Working with Others

Unlike working on yourself, in relating to other people it is important to work with, not against, their Enneagram type. The aim is to recognise and respect - even celebrate - the differences between their ways of being, thinking and feeling and your own.

If you can do this, it will not only make them feel valued and understood, it will make the relationship easier, more fulfilling and (in a work context) more productive for all concerned.

3. At Work

Supposing you are a Two (Helper) with responsibility for managing an Eight (Leader) and a Four (Romantic). As you yourself are typically eager to help others, it would be easy for you to fall into the trap of assuming others have the same motivation. So when allocating a task to one of your staff, it might seem natural to tell them how helpful it will be if they complete it quickly, and how much they will be appreciated by others. Unfortunately ‘appreciation’ is not a key motivator for either Eights or Fours, so you could well become frustrated by their apparent lack of enthusiasm for the task. Yet the real problem is that you have not spoken to each of them ‘in their own language’ and you have failed to appeal to their core values

- power and justice (Eight) or authenticity and originality (Four).

So supposing you were to approach the Eight slightly differently

- instead of talking about helpfulness and appreciation, tell her that you have selected her for the task as it is a tough assignment and will require strength of character to overcome entrenched opposition. Emphasise the essential justness of the outcome and that success will represent a victory for right over wrong; the Eight will feel valued for her strength and eager to exercise it in the service of a just cause. (If this seems slightly melodramatic and overly ‘confrontational’, remember that is 170

your perspective as a conciliatory Two, and that some tasks do require a firmer hand.)

Similarly, supposing you were to take the Four aside and let him know that you have selected him for this task because it requires someone with an original perspective, who will not be overly influenced by received ideas within the organisation, and who can be relied upon to stay true to himself even when others are challenging him. Tell him that considerable creativity will be needed to find a solution that sidesteps others’ objections and results in a memorable and distinctive outcome.

(If this sounds as though you are pushing him ‘out on a limb’, remember that is your perspective as a Two with a strong need for connection with others, and that Fours often relish their

‘outsider’ status.)

4. Personal Relationships

A few years ago there were posters all over London for a play called “I Love You, You’re Perfect” -

Now Change. I never saw the play, but couldn’t help smiling every time I saw the posters – they summed up so much about the expectations we place on partners and others who get close to us. When we first meet someone, we are struck by how new and exciting they are - we are entranced by their personality and the aura that surrounds them, and we find ourselves idolising them, including all the ways they are different to us.

Fast forward a few years (or even months) and the aura often fades, so that differences that were once charming can become confusing or even irritating. We start to notice their ‘faults’ and can’t help offering gentle hints and constructive criticism to help them overcome them - and get back to being the wonderful person we first met.

171

According to conventional wisdom, this is because we were intoxicated by love and placing them on a pedestal - the more time we spend with them, the more their true nature is revealed and we see their flaws. But the poet W.H. Auden argued that conventional wisdom has got things the wrong way round - it is when we first meet someone that we see them as they truly are, and later on, it is our own faults projected onto them that spoils the picture - and if we are not careful, the relationship.

As far as I know Auden was not familiar with the Enneagram but his attitude is very close to the way the Enneagram encourages us to relate to others - by looking for the source of conflict in our own skewed perceptions and assumptions, rather than seeing it as a fault in the other person.

So for example, a Three (Performer) and a Five (Observer) might fall in love - the Three entranced by the ‘mystery’ of the unfathomable Five, and the Five bowled over by the ‘glamour’ of the confident, successful Three. But conflict will arise whenever the Three fails to understand why the Five doesn’t ‘push herself forward more’ and gain more rewards and recognition for her knowledge and insights. Equally, the Five needs to watch out for her tendency to judge the Three as ‘shallow and materialistic’ in his pursuit of worldly success.

Having spent a fair amount of time working as a couples therapist, I’ve noticed it represents a significant turning point when two partners learn to let go of their expectations that the other should change, and learn to respect their differences -

however irritating or strange they might appear! In terms of the Enneagram, this means accepting the other’s type and dropping the unspoken demand that they become more like our type. In the above example