THE VENGEANCE OF LUCAS

HE little adobe house stood flush with the street, halfway between the business houses and the residence portion of the town which turned its back on the sand and sage-covered hills that—breaking into gray waves—far off cast themselves on the beach of blue skyland in great breakers of snow-crested mountains.

At the side of the house was a dooryard—so small!—beaten hard and smooth as a floor, and without a tree or a bush. There was no grass even at the edge of the sturdy little stream that ran across the square enclosure, talking all day to the old-faced baby in its high chair under the shake-covered kitchen porch. All day the stream laughed and chattered noisily to the owl-eyed baby, and chuckled and gurgled as it hurried across the yard and burrowed under the weather-bleached boards of the high fence, to find its way along the edge of the street, and so on to the river a quarter of a mile below. But the wee woman-child, owl-eyed and never complaining, sat through the long sunshine hours without one smile on its little old face, and never heeding the stream.

As the days grew hotter, its little thin hands became thinner, and it ate less and less of the boiled arroz and papas the young mother sometimes brought when she came to dip water.

“Of a truth, there is no niña so good as my ’Stacia; she never, never cries! She is no trouble to me at all,” Carmelita would exclaim, and clap her hands at the baby. But the baby only grew rounder eyed as it stared unsmilingly at its mother’s pretty plumpness, and laughing red lips, and big black eyes, whenever she stopped to talk to the little one.

Carmelita—pretty, shallow-pated Carmelita—never stayed long with the tiny ’Stacia, for the baby was so good left alone; and there was always Anton or Luciano and Monico to drop in for a laugh with the young wife of stupid old Lucas; or Josefa coming in for a game of “coyote y gallos.”

It was Lucas who went out to the porch whenever he could spare the time from earning money that he might buy the needed arroz and papas, or the rose-colored dresses he liked to see her wear.

It was for Lucas she said her first word—the only word she had learned yet—“papa!” And she said it, he thought, as if she knew it was a love in no wise different from a father’s love that he gave her, poor little Anastacia, whose father—well, Lucas had never asked Carmelita to tell him. How could he? Poor child, let her keep her secret. Pobre Carmelita! Only sixteen and no mother. And could he—Lucas—see her beaten and abused by that old woman who took the labor of her hands and gave her nothing in return?—could he stand by when he saw the big welts and bruises, and not beg her to let him care for her and the niña?—such a little niña it was, too! Of a verity, he was no longer young; and there was his ugly pock-marked face, to say nothing of the scars the oso had given him that day when he, a youth, had sent his knife to the hilt in the bear that so nearly cost him his life. The scars were horrible to see—horrible! But Carmelita (so young—so pretty!) did not seem to mind; and when the priest came again they were married, so that Carmelita had a husband and the pobrecita a father.

And such a father! How Lucas loved his little ’Stacia! How tender he was with her; how his heart warmed to the touch of her lips and hands! Why, he grew almost jealous of the red-breasted robin that came daily to sit by the edge of her plate and eat arroz with her! He begrudged the bird its touch of the little sticky hand covered with grains of rice which the robin pecked at so fearlessly. And when the sharp bill hurt the tender flesh, how she would scold! She was not his ’Stacia then at all—no, some other baby very different from the solemn little one he knew. There seemed something unearthly in it, and Lucas would feel a sinking of his heart and wish the bird would stay away. It never came when others were there. Only from the shelter of window or doorway did he and the others see the little bright bird-eyes watch—with head aslant—the big black ones; or hear the baby bird-talk between the two. Every day throughout the long, hot summer the robin came to eat from the niña’s plate of rice as she sat in her high chair under the curling shake awning; and all the while she grew more owl-eyed and thin. A good niña, she was, and so little trouble!

One day the robin did not come. That night, through the open windows of the front room, passers-by could see a table covered with a folded sheet. A very small table—it did not need to be large; but the bed had been taken out of the small, mean room to give space to those who came to look at the poor, little, pinched face under a square of pink mosquito bar. There were lighted candles at the head and feet. Moths, flying in and out of the wide open window, fluttered about the flames. The rose-colored dress had been exchanged for one that was white and stiffly starched. Above the wee gray face was a wreath of artificial orange blossoms, but the wasted baby-fingers had been closed upon some natural sprays of lovely white hyacinths. The cloying sweetness of the blossoms mingled with the odor of cigarette smoke coming from the farther corners of the room, and the smell of a flaring kerosene lamp which stood near the window. It flickered uncertainly in the breeze, and alternately lighted or threw into shadow the dark faces clustered about the doorway of the second room. Those who in curiosity lingered for a moment outside the little adobe house could hear voices speaking in the soft language of Spain.

To them who peered within with idle interest, it was “only some Mexican woman’s baby dead.” Tomorrow, in a little white-painted coffin, it would be born down the long street, past the saloons and shops where the idle and the curious would stare at the procession. Over the bridge across the now muddy river they would go to the unfenced graveyard on the bluff, and there the little dead mite of illegitimacy would be lowered into the dust from whence it came. Then each mourner in turn would cast a handful of earth into the open grave, and the clods would rattle dully on the coffin lid. (Ah, pobre, pobre Lucas!) Then they would come away, leaving Carmelita’s baby there underground.

Carmelita herself was now sitting apathetically by the coffin. She dully realized what tomorrow was to be; but she could not understand what this meant. She had cried a little at first, but now her eyes were dry. Still, she was sorry—it had been such a good little baby, and no trouble at all!

“A good niña, and never sick; such a good little ’Stacia!” she murmured. Carmelita felt very sorry for herself.

Outside, in the darkness of the summer night, Lucas sat on the kitchen porch leaning his head against the empty high chair of the pobrecita, and sobbed as if his heart would break.

That had happened in August. Through September, pretty Carmelita cried whenever she remembered what a good baby the little Anastacia had been. Then Josefa began coming to the house again to play “coyote y gallos” with her, so that she forgot to cry so often.

As for Lucas, he worked harder than ever. Though, to be sure, there were only two now to work for where there had been three. With Anton, and Luciano, and Monico, he had been running in wild horses from the mountains; and among others which had fallen to his share was an old blaze-face roan stallion, unmanageable and full of vicious temper. They had been put—these wild ones—in a little pasture on the other side of the river; a pasture in the rancho of Señor Metcalf, the Americano. And the señor, who laughed much and liked fun, had said he wanted to see the sport when Lucas should come to ride the old roan.

Today, Lucas—on his sleek little cow-horse, Topo—was riding along the river road leading to the rancho; but not today would he rope the old blaze-face. There were others to be broken. Halfway from the bridge he met little Nicolás, who worked for the señor, and passed him with a pleasant “Buenos dias!” without stopping. The boy had been his good amigo since the time he got him away from the maddened steer that would have gored him to death. There was nothing ’Colás would not do for his loved Lucas. But the older man cared not to stop and talk to him today, as was his custom; for he was gravely thinking of the little dead ’Stacia, and rode on. A hundred yards farther, and he heard the clatter of a horse’s hoofs behind him, and Nicolás calling:

“Lucas! Lucas!”

He turned the rein on Topo’s neck, and waited till the boy came. In the pleasant, warm October sunlight he waited, while Nicolás told him that which would always make him shiver and feel cold when afterward he should remember that half-hour in the stillness and sunshine of the river road. He waited, even after Nicolás (frightened at having dared to tell his friend) had gone.

The señor and Carmelita! It was the truth—Nicolás would not lie. The truth; for the boy had listened behind the high fence of weather-beaten boards, and had heard them talk together. He, and the little stream that gurgled and laughed all day, had heard how they—the señor and Carmelita—would go away to the north when the month should end. For many months they two had loved—the Señor Metcalf and the wife of Lucas; had loved before Lucas had made her his wife—ay! even before the little ’Stacia had come. And the little ’Stacia was the señor’s—— Ah, Lucas would not say it of the dead pobrecita! For she was his—Lucas’s—by right of his love for her. Poor little Anastacia! And but that the little one would have been a trouble to the Americano, they—the woman and the man—would have gone away together before; but he would not have it so. Now that the little one was no longer to trouble them, he would take the mother and go away to the new rancho he had just bought far over on the other side of the mountains.

“Their eyes met.”—

“Go!”—said Lucas, when the boy had finished telling all he had overheard—“Go and tell the señor that I go now to the corral to ride the roan stallion. And—’Colás, give to me thy riata for today.”

Lucas had driven the horses into one of the corrals. Alone there he had lassoed the old blaze-face; and then had driven the others out. Unaided, he had tied the old stallion down. As he lay there viciously biting and trying to strike out with his hind feet, Lucas had fastened a halter on his head and had drawn a riata (sixty feet long, and strong as the thews of a lion) tight about him just back of the forelegs. Twice he had passed it about the heaving girth of the old roan, whose reeking body was muddy with sweat and the grime and dust of the corral. The knots were tied securely and well. The rope would not break. Had he not made it himself from the hide of an old toro? From jaw-piece to jaw-piece of the halter he drew his crimson silk handkerchief, bandaging the eyes that gleamed red under swollen and skinned lids. Then, cautiously, Lucas unbound the four hoofs that had been tied together. The horse did not attempt to move, though he was consumed by a rage against his captor that was fiendish—the fury of a wild beast that has never yet been conquered.

Lucas struck him across the ribs with the end of the rope he was holding. The big roan head was lifted from the ground a second and then let fall, as he squealed savagely. Again the rope made a hollow sound against the heaving sides. Again the maddened horse squealed. When the rope struck the third time, he gathered himself together uncertainly—hesitated—struggled an instant—staggered to his feet, and stood quivering in every muscle of his great body. His legs shook under him; and his head—with the bandaged eyes—moved from side to side unsteadily.

Then Lucas wound the halter-rope—which was heavy and a long one—around the center-post of the corral where they were standing.

As he finished, he heard someone singing; the voice coming nearer and nearer. A man’s voice it was, full and rich, caroling a love song, the sound mingling with that of clattering hoofs.

Lucas, stooping, picked up the riata belonging to Nicolás. He was carefully re-coiling it when Guy Metcalf, riding up to the enclosure, looked down into the corral.

“Hello, Lucas! ‘Going to have some fun with the old roan,’ are you? Well, you’re the boy to ride him. ‘Haven’t got the saddle on yet, hey?’ Hold on a minute—— Soon as I tie, I’ll be with you!”

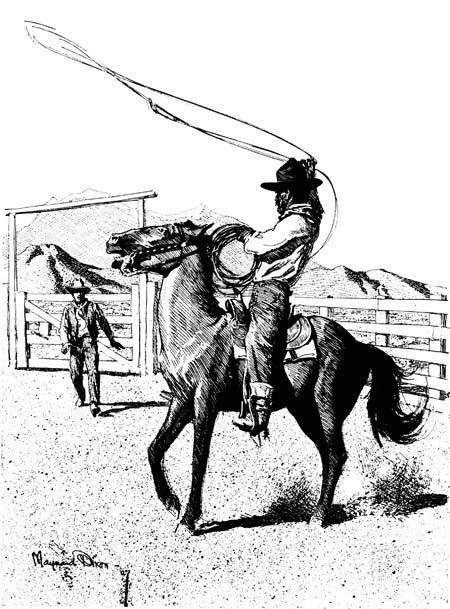

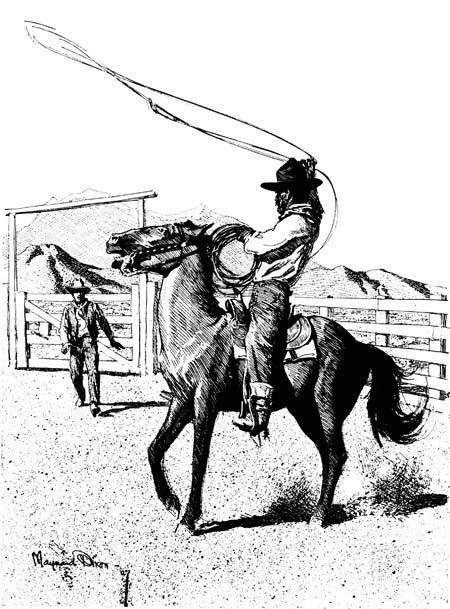

Lucas had not spoken, neither had he raised his head. He went to where little Topo was standing. Shaking the noose into place by a turn or two of the wrist, while the long loop dragged at his heels through the dust, he put his foot in the stirrup and swung himself into the saddle. He glanced at the gate—he ran the noose out yet a little more. Then he began to swing it slowly in easy, long sweeps above his head while he waited.

The gate opened and Metcalf came in. He turned and carefully fastened the gate behind him. He was a third of the way across the corral when their eyes met.

Then—with its serpent hiss of warning—the circling riata, snake-like, shot out, fastening its coils about him. And Topo, the little cow-horse trained to such work, wheeled at the touch of the spur as the turns of the rope fastened themselves about the horn of the saddle, and the man—furrowing the hoof-powdered dust of the corral—was dragged to the heels of the wild stallion. Lucas, glancing hastily at the face, earth-scraped and smeared and the full lips that were bleeding under their fringe of gold, saw that—though insensible for a moment from the quick jerk given the rope—the blue eyes of the man were opening. Lucas swung himself out of the saddle—leaving Topo to hold taut the riata. Then he began the work of binding the doomed Americano. When he had done, to the doubled rope of braided rawhide that was about the roan stallion, he made Carmelita’s lover fast with the riata he had taken from Nicolás. He removed it slowly from the man’s neck (the señor should not have his eyes closed too quickly to the valley through which he would pass!) and he put it about the body, under the arms. Lucas was lingering now over his work like one engaged in some pleasant occupation.

The halter-rope was then unknotted, and the turns unwound from the center-post. Next, he pulled the crimson handkerchief from the horse’s eyes—shouted—and shook his hat at him!

Maddened, terrified, and with the dragging thing at his heels, the four-footed fury fought man, and earth, and air about him like the very demon that he was till he came to the gate that Lucas had set wide for him, and he saw again the waves of sage and sand hills (little waves of sweet-scented sage) that rippled away to the mountains he knew. Out there was liberty; out there was the free life of old; and there he could get rid of the thing at his heels that—with all his kicking, and rearing, and plunging—still dragged at the end of the rope.

Out through the wide set gate he passed, mad with an awful rage, and as with the wings of the wind. On, and on he swept; marking a trail through the sand with his burden. Faster and faster, and growing dim to the sight of the man who stood grim and motionless at the gate of the corral. Away! away to those far-lying mountains that are breakers on the beach of blue skyland!