On the Eschatology of the Human Condition

We are now facing a crisis concerning the availability of an assured supply of energy and other resources to feed the ravenous productive capacity of our society. Complicating this critical situation is the problem of controlling the unwanted byproducts of production and consumption. Our present situation stands in striking contrast to the ubiquitous pattern of growth and expansion evidenced by nearly every aspect of what has come to be known as civilization during the past century. We can no longer avoid, nor dare we postpone, the obligation to investigate these issues in a serious and expeditious manner in order to ascertain whether the present reverses are but temporary diversions and fluctuations from a long range pattern of stable and sustainable growth, or whether they are harbingers of limits to expansion imposed by nature, limits which cannot be passed with impunity. Our investigation must, insofar as it is able, be scientific; stripping away the superficialities of mere experience in order to uncover the underlying motive forces which frame and mold the opportunities and constraints whose realizations we recognize in the continuing progression of daily events. As in so many fields whose mysteries have been revealed through diligent application of the methods of science, here too we may expect to find that superficial experience misleads and diverts the attention from the matter of essential significance.

In the issue at hand the lesson taught by the immediate experience of life in America and the other industrial nations is that continuing exponential growth, growth which cumulates according to the law of compound interest, growth without limit or constraint, is the natural human condition. The more reflective amongst us may examine the historical record to penetrate beyond the present and the immediate past, but they too find evidence to support the conclusion of immediate experience unless they search so far into the past that the very nature of society seems so different from our own as to invalidate any method or even hope of comparison. Yet the Malthusian critique, in forms more or less sophisticated, remains to haunt us in even the best of times with the suspicion that those early civilizations, so unlike our own, hold the key not only to the flowering of our recent past but also to a withered future.

Growth of human knowledge

There can be little doubt that immediate experience provides a firm foundation for the expectation of continued exponential growth. For example, we derive from human knowledge all our skills and abilities to turn the base matter of the world to our own interests. Knowledge grows with time; if we attempt to measure it---not by its essential quality, but by its quantity as manifested in reduction to printed form stored as books and journals in archival libraries---we find that knowledge, too, grows exponentially, apparently inexorably increasing by a fixed fraction year after year. Figure 1 exhibits the growth of the number of scientific journals with time --one typical measure of the growth of knowledge. The vertical axis scale is so arranged that exponential growth is represented by straight lines. The figure suggests that scientific knowledge has grown exponentially for more than 200 years, doubling its quantity every 15 years. If this pattern of growth persists for another two and one half decades, an addition of some 12% to the historic record represented by the figure, there will be in the year 2000 more than 1 million scientific journals publishing more than 25 million scientific articles each year. It has been calculated that each scientific article published today represents an investment of about $25,000; this cost will certainly not decrease in the future. Extrapolation of the historic trend of Figure 1.1 therefore entails the conclusion that annual investment in scientific effort in the year 2000 will reach nearly one trillion dollars, which is approximately the 1973 gross national product of the United States. If the trend continues until 2050, the investment in science will rise to 10 trillion dollars annually. We do not suggest that these estimates are predictions; rather, they have been introduced to provide the reader with a yardstick with which to measure the encouraging projections of the technological optimists who argue that the increased application of novel technology will relax current constraints which manifest themselves in the form of continual shortages rotating from food to productive capacity to energy and back again to food. Newton has already combed the beach, found the smoother pebbles and prettier shells; we must explore his great ocean of truth and the price of the vessel in which we can do this must be paid. If continuance of exponential growth is to depend on technology, and ultimately on science, then the growth of technology and science must themselves continue on their exponential path, and then the projections provided above will, no matter that they boggle common sense, foreshadow reality.

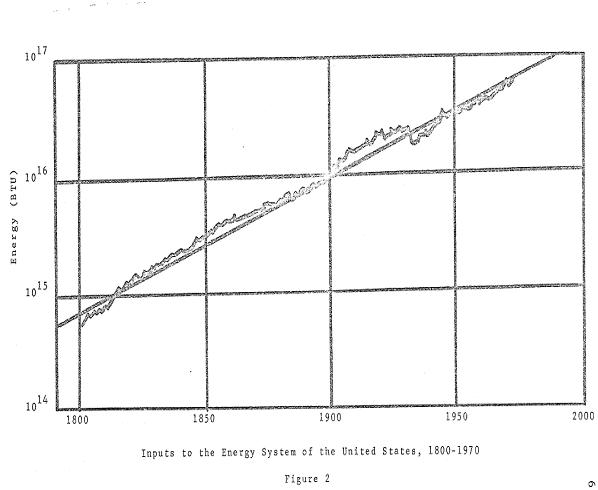

Growth of the energy system

The recent historic exponential growth of civilization is more apparent to us all in other ways. To consider a timely example: although the sources of energy used in the United States have changed dramatically since 1800, the growth of annual inputs to the energy system of this country has deviated but little from its exponential trend in the intervening 170 years. There was a slight relative excess from 1900 until the Great Depression in 1929 and a subsequent defect until the end of World War II, but the deviations from the exponential trend displayed in Figure 1.2 are small when compared with the enormous social dislocations with which they were associated, and they seem not to have any long term effect on the underlying growth pattern.

According to Figure 1.2, inputs to the energy system of the United States have been doubling every 26 years; they "should", if growth were to continue unchecked, double again between the present time (1974) and the year 2000. Thus, could we now provide sufficient energy merely to maintain present consumption levels, by the year 2000 we would find that we would be providing for but one-half our then "normal" requirements, based upon the hypothesis that the historic exponential growth trend in energy utilization reflects a natural and appropriate feature of civilization. Upon this hypothesis it follows that most Americans now alive will live to see the day when society will be able to assuage but half their "natural" craving for energy. On this scale, major oil discoveries such as the Alaskan North Slope field and the North Sea deposits diminish in stature: total North Slope recovery is anticipated to be equivalent to 3 years consumption for the United States at present usage rates. Our ability to provide energy in amounts that will continue to double every 26 years clearly demands major technological innovations and extensive capital investment. Assimilation of the byproducts of these efforts, social as well as substantial, may require still greater efforts and ingenuity.

It is sometimes thought that population growth is the essential driving force behind the general exponential growth of other components of society. That this is not so is readily seen by comparison of the rates of growth of United States population and of the inputs to the energy system of the United States. Recent population growth rates correspond to a doubling period of about 45 years compared with the 26 year doubling period for energy input growth; this simply means that per capita energy inputs have been growing. Nevertheless, population growth is an important component in the general scheme of expansion exhibited by our civilization, and one which affects the life style of individuals in a relatively direct way, for within an adult lifetime of 50 years an American can expect to see the population double (if trends continue). The effect would be a consequent major density increase in urban living areas, increased strains on commodity delivery and other communication systems, increased inequalities in the distribution of wealth, larger average community size, and an increasingly impersonal and depersonalized social life outside the spheres of friendship and work role. Contrast this situation with the life of the typical western European in the Middle Ages, say 700-1100: population growth was negligible during this period; personal mobility was low; and personal associations and interactions remained relatively stable throughout most people's lifespan.

Figure 1.3 shows that the population of the United States has changed in different ways at different times: in the earliest periods after European settlement, growth was

exponential and extremely rapid; from 1650 to about 1880, population growth was again exponential with virtually no deviations during this 230 year interval. Since 1880 there has been a marked decline in the rate of growth with irregularities which obscure the general trend features. We may nevertheless conclude that any American born between 1650 and 1850 could confidently conclude from personal experience and the historical record that exponential population growth is a natural feature of life in America. The marked change evident in the manner of growth of population during the period centered about 1880 calls for an explanation) and one is readily forthcoming. Prior to that period, there remained a western frontier which was, bit by bit, continually pushed back thereby effectively increasing the land area of the settled nation, until the constraint of fixed geographical and settled limits induced a change in the nature of population increase. Indeed, during the earlier periods, population increase in the United States did not necessarily lead to increased population density due to the effect of territorial expansion, so that, although more recent periods have seen smaller rates of growth, the local population density experienced by most Americans is probably increasing more rapidly now than before.

Alternative Possibilities

The analysis to this point appears to confirm the generality of exponential growth for various important segments of civilization over periods of time significantly longer than a single generation. The feature of change in the rate of growth of United States population also suggests that there are some mechanisms which can distort or perhaps even destroy the operation of exponential increase. Let us turn our attention to the determination of what these might be and whether they and their effects are intrinsic and unavoidable, or extrinsic and removable.

We would like, of course, to be able to experiment with numerous identical copies of our world with all its inhabitants and curiosities, subjecting each replica to a distinct set of circumstances and following each along its future path to its terminus, thus we could establish the more and the less desirable modes of development which are open to us, asses their benefits and costs, and learn how to direct ourselves and our posterity, if not to the best of all possible worlds, at least away from the worst. That this option is not open to us should not act as a deterrent to serious consideration of the multiple possibilities the future holds, for there are still two ways left to proceed. The more refined founds itself on a deep idea of Maxwell, who in his study of the statistical properties of gases, conceived an infinite ensemble of ideal replicas of the system of actual interest which populated, in his thoughts if not in reality, the various ideally possible physical states. Maxwell then sought to identify the most probable of these states with the state which, apart from certain relatively negligible fluctuations, actually obtained. His efforts created the important and successful discipline of statistical mechanics and set a potential pattern for the study of social systems which has not yet received the attention it deserves.

The second method is much more concrete and analogical, and consequently more narrow in its assertions and less certain in its implications. It consists of finding analogues, or models, of aspects of human civilization, primarily amongst the micro-organisms and insects which run through their life cycles at rates so great that the birth, development, and death of their “societies” and the eschatology of their condition can be followed and documented during an interval brief according to the standards of change of our civilizations. But a fundamental problem always intrudes: to what extent is it permissible to generalize from the rise and fall of the fruit fly Drosophila to the rise and fall of Rome, or of humanity itself? We cannot answer this question, but we also cannot avoid the belief that one of the most pressing problems which confronts anyone concerned with the future of humanity is the determination of whether, and if so, how, human society differs from the societies of lower forms insofar as the great forces which govern growth and decay are concerned.

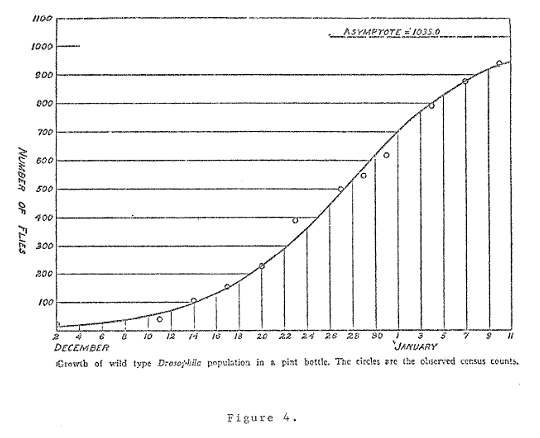

Consider, for instance, the life cycle of a population of wild type Drosophila grown in a pint bottle, as illustrated in Figure 1.4. It is clear from that figure that the population

does not increase indefinitely and exponentially, but rather approaches, after some brief time, an absolute limiting value beyond which it cannot pass. It is probable that no Drosphila savant would assert that either the historical record or common sense suggest that exponential growth is the norm for Drosphila society, as it generally seems and has seemed to be for us. Yet there is a certain lawfulness in the pattern of population growth displayed in Figure 1.4, called logistic growth, whose exact form need not concern us here. Suffice it to say that by means of a formula, not more complex than that which describes exponential growth itself, the calculations shown in the rightmost column of the Table below were obtained, which show a striking agreement with the observed population.

Table 1.1. Growth of Wild Type Drosophilia Population in a Pint Bottle| Date of census | Observed population | Calculated population from equation |

|---|

| December 2 | 22 | 14.3 |

| December 11 | 39 | 61.0 |

| December 14 | 105 | 96.7 |

| December 17 | 152 | 150.2 |

| December 20 | 225 | 226.0 |

| December 23 | 390 | 326.0 |

| December 27 | 499 | 488.4 |

| December 29 | 547 | 574.1 |

| December 31 | 618 | 656.8 |

| January 4 | 791 | 798.4 |

| January 7 | 877 | 877.1 |

| January 10 | 938 | 932.9 |

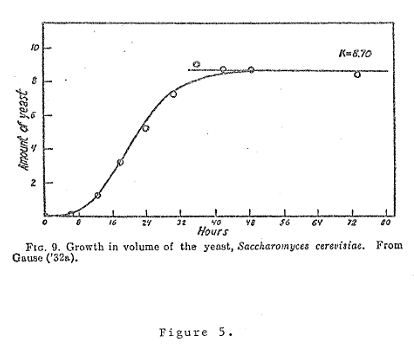

The logistic growth pattern is as common amongst short lived rapidly reproducing lower life forms as the exponential pattern is amongst humans, and amongst people-related phenomena such as knowledge and energy inputs. Figure 5 displays the life cycle of a society of yeast cells; once again, the presence of an absolute limit beyond which population apparently cannot press is evident, and once again, the logistic mathematical description is appropriate.

In order to draw the connection between these societal microcosms which pass, from our vantage point, so quickly, through all their phases, let us reconsider the data for the yeast cell population of Figure 1.5 expressed with respect to the semi-logarithmic vertical scale such as used in Figure 1.1, and in terms of which exponential growth corresponds to straight lines. Figure 1.6, so drawn, shows that for the first 6 hours of growth, the yeast population does in fact increase exponentially, but thereafter a rapid decline in the rate of increase becomes apparent, leading after another 6 hours to a stagnant population whose numbers barely change until termination of the experiment. The reader can hardly help but notice the approximate correspondence between the early and middle periods of Figure 1.6 with the corresponding periods of exponential growth of United States population from 1650 to 1880, and the subsequent decline in the rate of increase after 1880 displayed in Figure 1.3. Are we certain that we are different from Drosophila, or from yeast cells, insofar as the cycle of population is concerned? If we are certain, on what do we base our certainty?

Figure 1.4, Figure 1.5, and Figure 1.6 do not convey the full picture of the life cycle of a microscosmic society as it is now known, for they do not follow developments far enough into the future.

If the life cycle of the microcosmic Drosophia and yeast populations are similar to the human cycle of population and societal growth, then the former confirms our explanation of the cause of the deviation from exponentiality of the population growth of the United States) shows that it is essentially inevitable, and promises analogous declines in growth rate and asymptotic approach to stable maximum states for world population and possibly for energy consumption, productivity, growth of knowledge, etc., as well.

It is not difficult to envision this equilibrium state and its corresponding equilibrium society as a paradise) finally freed from the pressures and problems created by incessant population growth and its derivative phenomena, and granted the option to accommodate its desires to its means in a gradual evolutionary manner. But such a society would, necessarily, differ greatly from that to which we have become accustomed, in which savings bank deposits and corporate income offer fixed annual fractional returns by some fiducial duplication of the theological miracle of the creation of substance and value from null and void. The equilibrium society apparently promised by the Drosophila and yeast civilizations will necessarily be one of decreased personal and social mobility, decreased personal opportunity, and no doubt of decreased excitement. Each of us will have different views of the desirability of such stable circumstances.

Figure 1.4, Figure 1.5, and Figure 1.6 paint, in fact, too cheerful a picture of the population life cycle of microcosmic societies, and by implication, of our own potential future, for they do not follow developments far enough into the future. They misleadingly present the impression that an ultimate stable state of maximum population is attained by gradual increase from earlier states; they carry the implication that once society has adapted to the relatively rapid and critical conversion from exponential growth, displayed, for instance, from hours 7 through 12 in Figure 1.6, a uniform and hence rather crisis-free period of unlimited duration will follow --- a period perhaps bland, possibly undesirable in certain aspects, but one at least stable. Unfortunately this is not the case, for the same forces which worked to constrain and limit exponential growth, converting it into a type of growth which is subject to an absolute upper bound as displayed in Figure 1.4, Figure 1.5, and Figure 1.6, continue to work even as population closes upon the maximum value.

In the microscosmic societies these forces of constraint are imposed, on the one hand, by the geometrical restraints of the finiteness of the environment, pint bottle or Petrie dish; and on the other by the related twin factors of resource depletion and non-absorption of the byproducts of metabolism, which we generally will interpret for our more complex situation as “pollution”. Whereas the direct effect of the finite environment is the absolute limitation of population, the ultimate effect of resource depletion and increasing pollutant density is a gradual diminution of the maximum value of the population that the limited environment will support. When combined, these factors suggest that the life cycle figure should in its earliest stages display unconstrained exponential growth of population when the population density is small and the ability of the environment to supply necessary resources and diffuse undesirable societal byproducts is correspondingly great, Thereafter, a period should follow wherein the geometrical constraints of the finiteness of the environment enforce an absolute limit on the supportable population. These two stages are exhibited in Figure 1.4, Figure 1.5, and Figure 1.6, and the cycle of United States population growth displays the first and the early effects of the second (