(protozoan)

mos quito vector

meningitis, necrotizing

Group A Streptococcus

uncertain

fasciitis (flesh-eating

(bacterium)

disease), toxic-shock

syndrome, and other

diseases

pertussis

Bordetella pertussis

refusal to vaccinate based on fears the vaccine is not

(whooping cough)

(bacterium)

safe; other possible factors: decreased vaccine efficacy

or waning immunity among vaccinated adults

polio (infant paralysis)

poliovirus

–

rabies

rabies virus

breakdown in public health measures; changes in

land use; travel

Rift Valley fever (RVF)

RVF virus

–

rubeola (measles)

measles virus

failure to vaccinate; failure to receive second dose of

vaccine

schistosomiasis

Schistosoma species

dam construction; ecological changes favoring snail

(helminth)

host

trypanosomiasis

Trypanosoma brucei

human population movements into endemic areas

(protozoan)

due to political conflict; diagnosis is very difficult,

and current treatments have severe secondary effects

tuberculosis

Mycobacterium

antibiotic-resistant pathogens; immunocompro mised

tuberculosis (bacterium)

populations (malnourished, HIV-infected, poverty-

stricken)

West Nile encephalitis

West Nile virus

complex interactions between the virus, birds and

other animals, mosquitoes, and the environment;

emergence in U.S. and other regions likely due to

global travel

yellow fever

yellow fever virus

insecticide resistance; urbanization; civil strife

Sources: Krause, R.M. 1992. The origin of plagues: Old and new. Science, 257: 1073–1078; Measles—United States, 1997. 1998, April 17.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47(14): 273–276; Pertussis vaccination: Use of acel ular pertussis vaccines among infants and young children. 1997, March 28. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 46(RR-7); ProMED. 1994. About ProMED. Available from

http://www.fas.org/promed/about/index.html. June 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/

preview/mmwrhtml/mm6115a1.htm. July 2013.

Note about rubeola: After the initial decline of measles cases after the licensing of the vaccine in 1963, there was a resurgence of measles—to some 50,000 cases—from 1989 to 1991. Since then, the incidence of measles declined to a median of 60 cases per year between 2000 and 2010, and then increased to 222 in 2011.

34

by researchers funded by NIH and others. These

individuals, families, communities, institutions,

drugs, when used in combination with other

and society. Here, an “interest” refers to a

anti-HIV drugs, are responsible for the dramatic

participant’s share or participation in a situation.

decrease in deaths from AIDS in the United

The terms “wrong” or “bad” apply to those actions

States. One active area of research at NIH is the

and qualities that impair interests.

development of new types of vaccines based on

our new understanding of the immune system. In

Ethical considerations are complex and multifaceted,

addition, basic research on the immune system and

and they raise many questions. Often, there are

host-pathogen interactions has revealed new points

competing, well-reasoned answers to questions

at which vaccines could work to prevent diseases.

about what is right and wrong and good and

bad about an individual’s or group’s conduct or

Finally, basic research on the ecology of disease

actions. Thus, although science has developed

organisms—their reservoirs, modes of transmission,

vaccines against many diseases, and professional

and vectors, if any—reveals points at which

medical recommendations encourage their

preventive measures can be used to interrupt

widespread use, individuals are permitted (in

this cycle and prevent the spread of disease. For

most, but not all, states) to choose not to be

example, research supported by NIAID delineated

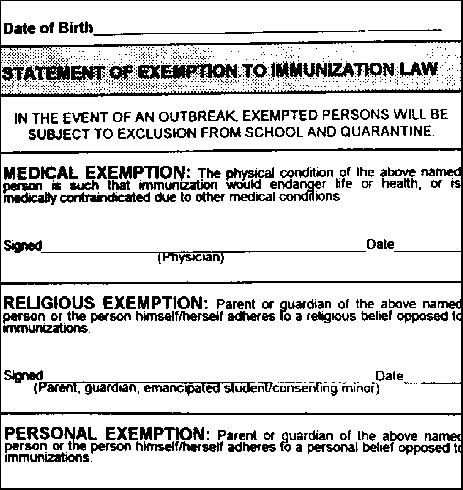

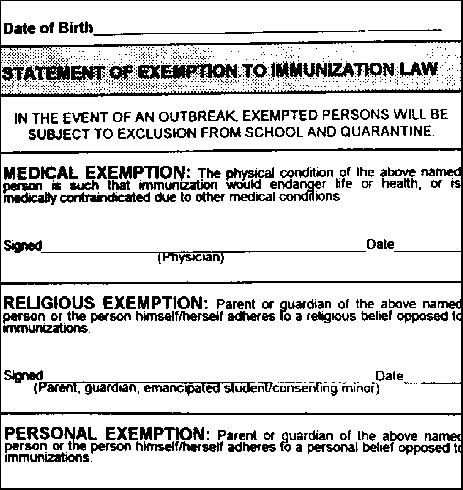

vaccinated. (Figure 7)

the mechanism of Lyme disease transmission and

how disease results: The tick vector was identified

Typically, answers to these questions all involve

and the life cycle of the causative bacterium was

an appeal to values. A value is something that

traced through deer and rodent hosts. Understanding

has significance or worth in a given situation.

this ecology has led to predictions about the

One of the exciting events to witness in any

regions where and years when the threat of Lyme

discussion in ethics in a pluralist society is

disease is greatest, as well as recommendations to

the varying ways in which the individuals

the public for avoiding infection. These examples

involved assign value to things, persons, and

and others demonstrate that investment in basic

states of affairs. Examples of values that students

research has great long-term payoffs in the battle

may appeal to in discussions of ethical issues

against infectious diseases.

Infectious Diseases and Society

Figure 7. Most states allow exemptions to

What are the implications of using science to

immunization law.

improve personal and public health in a pluralist

society? As noted earlier, one of the objectives

of this module is to convey to students the

relationship between basic biomedical research

and the improvement of personal and public

health. One way to address this question is by

attending to the ethical and public policy issues

raised by our understanding and treatment of

infectious diseases.

Ethics is the study of good and bad, right and

wrong. It has to do with the actions and character

of individuals, families, communities, institutions,

and societies. During the past two and one-half

millennia, Western philosophy has developed a

variety of powerful methods and a reliable set of

concepts and technical terms for studying and

talking about the ethical life. Generally speaking,

we apply the terms “right” and “good” to those

actions and qualities that foster the interests of

35

Understanding Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases

Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases

include autonomy, freedom, privacy, protecting

Third, because tradeoffs among interests are

another from harm, promoting another’s good,

complex, constantly changing, and sometimes

justice, fairness, economic stability, relationships,

uncertain, discussions of ethical questions often

scientific knowledge, and technological progress.

lead to very different answers to questions about

what is right and wrong and good and bad. For

Acknowledging the complex, multifaceted

example, we acknowledge that individuals have a

nature of ethical discussions is not to suggest

right to privacy regarding their infectious disease

that “anything goes.” Experts generally agree

status. Yet, some argue that AIDS patients who

on the following features of ethics. First, ethics

knowingly infect others should have their right

is a process of rational inquiry. It involves

to privacy overridden so that partners may be

posing clearly formu lated questions and seeking

notified of the risk of contracting AIDS.

well-reasoned answers to those questions. For

example, developing countries and isolated

It is our hope that completing the activities in this

rural areas suffer particularly severely from

module will help students see how understanding

many infectious diseases because conditions of

science can help individuals and society make

crowding and poor sanitation are ideal for the

reasoned decisions about issues relating to

growth and spread of pathogens. The same is

infectious diseases and health. Science provides

true for many inner-city environments. These

evidence that can be used to support ways of

places provide a constant reservoir of disease-

understanding and treating human disease, illness,

causing agents. We can ask questions about what

deformity, and dysfunction. But the relationships

constitutes an appropriate ethical standard for

between scientific information and human choices,

allocating healthcare funds for curtailing the

and between choices and behaviors, are not linear.

spread of infectious diseases. Should we expend

Human choice allows individuals to choose against

public research dollars to develop drugs whose

sound knowledge, and choice does not necessarily

cost will be out of reach for developing countries?

lead to particular actions.

Is there any legal and ethical way for the United

States to prevent over-the-counter sales of

Nevertheless, it is increasingly difficult for most

antibiotics in other countries, a practice that

of us to deny the claims of science. We are

may enhance the evolu tion of antibiotic-resistant

continually presented with great amounts of

pathogens? Well-reasoned answers to ethical

relevant scientific and medical knowledge that

questions constitute arguments. Ethical analysis

is publicly accessible. As a consequence, we can

and argument, then, result from successful

think about the relationships among knowledge,

ethical inquiry.

choice, behavior, and human welfare in the

following ways:

Second, ethics requires a solid foundation of

information and rigorous interpretation of that

knowledge (what is known and not known)

information. For example, one must have a solid

+ choice = power

understanding of infectious disease to discuss the

ethics of requiring immunizations and reporting

power + behavior = enhanced human welfare

of infectious diseases. Ethics is not strictly a

(that is, personal and public health)

theoretical discipline but is concerned in vital

ways with practical matters. This is especially

One of the goals of this module is to encourage

true in a pluralist society.

students to think in terms of these relationships,

now and as they grow older.

36

References

Anderson, R.M., and May, R.M. 1992. Infectious

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control.

(CDC). 1994. Addressing emerging infectious

New York: Oxford University Press.

disease threats. A prevention strategy for the

United States. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. 1999.

Teaching Tools. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt

Chan, E.H., et al. 2010. Global capacity for

Publishing Company.

emerging infectious disease detection.

Proceedings of the National Academy

Black, Jacquelyn G. Microbiology: Principles

of Sciences USA 107: 21701-21706.

and Explorations, 6th Edition. Hoboken, NJ:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 471-42084-0

Cohen, M.L. 1992. Epidemiology of drug

resistance: Implications for a post-

Board on Global Health. 2003. Microbial

antimicrobial era. Science, 257: 1050–

Threats to Health: Emergence, Detection,

1055. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/

and Response. Washington, DC: National

reprint/257/5073/1050.pdf

Academies Press.

Committee on Microbial Threats to Health,

Bonwell, C.C., and Eison, J.A. 1991. Active

Institute of Medicine. 1992. Emerging

Learning: Creating Excitement in the

infections: microbial threats to health in the

Classroom. (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education

United States. Washington, DC: National

Report No. 1.) Washington, DC: The George

Academies Press.

Washington University: School of Education

and Human Development. http://www.oid.

Corrigan, P., Watson, A., Otey, E., Westbrook,

ucla.edu/about/units/tatp/old/lounge/pedagogy/

A., Gardner, A., Lamb, T., et al. 2007.

downloads/active-learning-eric.pdf.

How do children stigmatize people with

mental illness? Journal of Applied Social

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., and Cocking,

Psychology, 37(7): 1405–1417.

R.R. 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind,

Experience, and School. Washington, DC:

Davies, J., and Webb, V. 1998. Antibiotic

National Academy Press.

resistance in bacteria. In R.M. Krause (Ed.),

Emerging Infections: Biomedical Research

Breman, J.G., de Quadros, C.A., and Gadelha, P.

Reports. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

(eds.). 2011. Smallpox eradication after 30 years:

lessons, legacies and innovations. Vaccine 29:

Fauci, A.S. 1998. New and re-emerging

Supplement 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

diseases: The importance of biomedical

research. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 4(3).

Brody, C.M. 1995. Collaborative or cooperative

ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/EID/vol4no3/ascii/fauc.txt

learning? Complementary practices for

instructional reform. The Journal of Staff,

Fauci, A.S., and Morens, D.M. 2012. The perpetual

Program, and Organizational Development,

challenge of infectious diseases. New England

12(3): 134–143.

Journal of Medicine 366: 454-461.

37

Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases

Garrett, L. 1994. The Coming Plague. New York:

Knapp, M.S., Shields, P.M., and Turnbull, B.J.

Penguin Books.

1995. Academic challenge in high-poverty

classrooms. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(10): 770–776.

Geier, R., Blumenfeld, P., Marx, R., Krajcik, J.,

Fishman, B., Soloway, E., and Clay-Chambers,

Krause, R.M. (Ed.) 1998. Emerging Infections:

J. 2008. Standardized test outcomes for

Biomedical Research Reports. San Diego, CA:

students engaged in inquiry based science

Academic Press.

curriculum in the context of urban reform.

Journal of Research in Science Teaching,

Lynch, S., Kuipers, J., Pyke, C., and Szesze, M.

45(8): 922–939.

2005. Examining the effects of a highly

rated science curriculum unit on diverse

Hickey, D.T., Kindfeld, A.C.H., Horwitz, P., and

students: Results from a planning grant.

Christie, M.A. 1999. Advancing educational

Journal of Research in Science Teaching,

theory by enhancing practice in a technology

42: 921–946.

supported genetics learning environment.

Journal of Education, 181: 25–55.

Measles—United States, 1997. 1998, April 17.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,

Howard Hughes Medical Institute. 1996.

47(14): 273–278.

The major killers. In The Race Against

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm4714.pdf.

Lethal Microbes, 6 (pp. 22–24).

Institute’s Office of Communications.

Minner, D.D., Levy, A.J., and Century, J. 2009.

Inquiry-based science instruction—

Howard Hughes Medical Institute. 1996.

what is it and does it matter? Results

The return of tuberculosis. In The Race

from a research synthesis years 1984 to

Against Lethal Microbes, 6. Institute’s

2002. Journal of Research in Science

Office of Communications.

Teaching, 47(4), 474-496.

Institute of Medicine. 2012. Improving Food

Moore, J.A. 1993. Science as a Way of Knowing:

Safety through a One Health Approach.

The Foundations of Modern Biology.

Workshop Summary. September 10, 2012.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Institute of Medicine. 2010. Infectious Disease

Morens, D.M., and Fauci, A.S. 2012. Emerging

Movement in a Borderless World. Workshop

infectious diseases in 2012: 20 years after

Summary. March 12, 2010.

the Institute of Medicine report. mBio

3(6):e00494-12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00494-12.

Institute of Medicine. 2009. Sustaining Global

Surveillance and Response to Emerging

Morens, D.M., Holmes, E.C., Davis, A.S., and

Zoonotic Diseases. September 22, 2009.

Taubenberger, J.K. 2011. Global rinderpest

eradication: lessons learned and why humans

Jamison, D.T., Mosley, W.H., and Measham,

should celebrate too. Journal of Infectious

A.R. (Eds.). 1993. Disease Control Priorities

Diseases 204- 502-505.

in Developing Countries. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Morse, S.S. 1993. Emerging Viruses. New York:

http://www.dcp2.org/pubs/DCP.

Oxford University Press.

Jones, K.E., et al. 2008. Global trends in

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious

emerging infectious diseases. Nature

Diseases (NIAID) Web site.

451: 990-994.

http://www.niaid.nih.gov/.

38

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious

Perkins, D. 1992. Smart Schools: Better Thinking

Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

and Learning for Every Child. New York:

2008. NIAID Research Agenda for Emerging

The Free Press.

Infectious Diseases.

Project Kaleidoscope. 1991. What Works:

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious

Building Natural Science Communities

Diseases (NIAID). 2008. NIAID Research

(Vol. 1). Washington, DC: Stamats

Agenda for Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Communications, Inc.

Available from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/

http://www.pkal.org/documents/VolumeI.cfm .

whoWeAre/profile/fy2004/Documents/research_

emerging_re-emerging.pdf.

Prusiner, S.B. 1995. The prion diseases.

Scientific American, 272: 48–57.

National Institutes of Health. 1996.

http://www.vanderbilt.edu/AnS/physics/brau/

Congressional justification. Bethesda, MD.

H182/Prusiner%20reading/PrionDiseases.pdf.

National Institutes of Health and Biological

Radetsky, P. 1998, November. Last days

Sciences Curriculum Study. 2005.

of the wonder drugs. Discover: 76–85.

The Science of Mental Illness. NIH

http://discovermagazine.com/1998/nov/

Curriculum Supplement Series.

lastdaysofthewon1535.

Washington, DC: Government Printing

Office. Available from http://science.education.

Randolph, S.E., and Rogers, D.J. 2010. The arrival,

nih.gov/supplements/mental.

establishment and spread of exotic diseases:

patterns and predictions. Nature Reviews

National Institutes of Health and Biological

Microbiology 8: 361-371.

Sciences Curriculum Study. 2003. Sleep,

Sleep Disorders, and Biological Rhythms.

Riley, L.W., et al. 1983. Hemorrhagic colitis

NIH Curriculum Supplement Series.

associated with a rare Escherichia coli

Washington, DC: Government Printing

serotype. New England Journal of Medicine,

Office. Available from http://science.education.

308: 681–685.

nih.gov/supplements/sleep.

Roblyer, M.D., Edwards, J., and Havriluk, M.A.

National Research Council. 1996. National

1997. Integrating Educational Technology

Scienc