Corruption—especially when it is prevalent in society—poses a threat to the larger social fabric. Why? Because it undermines the trust and shared values that make a society work. People pay taxes and offer allegiance to a government in return for security and essential public services, notes Raymond Gilpin at U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP). But, he adds, when those in government start to use public money for their own personal benefit and services start to collapse, then there is a breakdown of trust. Judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government also become compromised.

What Forms of Governance Are Likely to Be More Corrupt?

Corruption tends to be more prevalent in autocratic systems (where one person rules with unlimited authority), or oligarchies (rule by a small group of elites). As Minxin Pei from the Carnegie Endowment clarifies, corruption does exist in democracies, but it “is fundamentally different from the massive looting by autocrats in dictatorships. That is why the least corrupt countries, with a few exceptions, all happen to be democracies, and the most corrupt countries are overwhelmingly autocracies… That corruption is more prevalent in autocracies is no mere coincidence. While democracies derive their legitimacy and popular support through competitive elections and the rule of law, autocracies depend on the support of a small group of political and social elites, the military, the bureaucracy and the secret police.”11

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government and, historically, there are numerous examples of corrupt dictatorships. Take Mohamed Suharto, the president of Indonesia from 1967 to 1998. He reportedly embezzled $15 to 35 billion from state coffers. Suharto’s rule was very centralized and his government was dominated by the military. Although he maintained stability over an extensive region and boosted economic growth, his authoritarian regime was marked by renowned corruption and widespread discontent. Mobutu Sésé Seko, the president of Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) from 1965 to1997, also embezzled some $5 billion.12 Mobutu stayed in power by fostering a broad patronage network, handing foreign-owned firms over to relatives and associates, and publicly executing political rivals. Centralized systems like these rely on the support of a cadre of powerful elites, but the majority of the population has little political influence or other rights.

One-party states may also have higher potential for corruption because of the lack of “checks and balances” on their rule. Vietnam is an example of where one-party rule has led to systemic corruption and little accountability, notes Nathanial Heller at Global Integrity. All political organizations are under the control of the Vietnamese Communist Party. There is no independent media, or legally recognized opposition parties. In systems like Vietnam’s, adds Heller, everything goes through the party, which determines who gets promoted and where contract money goes.13 Without checks on a highly centralized form of governance and without a strong public voice that applies pressure on the government, transparency and accountability may be difficult to accomplish. Vietnam has been moving to a free-market economy. Hence, its government acknowledges, more work needs to be done to combat corruption in order to attract foreign investment.

Is Corruption Lower in Democracies?

Corruption exists in all societies and some would argue that you can minimize it, but never eliminate it anywhere. Despite this, a democratic system of government has some built-in mechanisms that keep corruption in check. Democracy is defined by USIP as “a state or community in which all members of society partake in a free and fair electoral process that determines government leadership, have access to power through their representatives, and enjoy universally recognized freedoms and liberties.” It is generally accepted that strong democracies have lower levels of corruption, largely because those who are ruled give the government the legitimacy to govern and therefore the citizens can hold the government to greater transparency in its operations.

However, even when a state has free and fair elections and calls itself a democracy, it may still be emerging from conflict, transitioning from authoritarian rule, or be guided by loyalties to one’s own clan, tribe, or interest group. A state may also have a political culture that lends itself to corrupt practices. In Russia, for example, there is a preference for cultivating access to influential people rather than adhering to formal and legalistic procedures and norms. Such a political culture continues to proliferate corruption and, as countries like Russia have transitioned to market economies, corruption has particularly benefited the well-connected and newly rich.14

In states transitioning from one form of governance to another, corruption may actually increase. “When authoritarian control is challenged and destroyed through economic liberalizations and political democratizations, but not yet replaced by democratic checks and balances and by legitimate and accountable institutions, the level of corruption will increase and reach a peak before it is reduced with increasing levels of democratic governance,” suggests a paper on corruption prepared in 2000 for the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.15 Many countries in the former Soviet Bloc, for example, have transitioned from Communism to multiparty democracies over the past 20 years, but corruption is still rife in many. In Bulgaria, for example, a variety of legal reforms have been put in place to combat corruption. However, corruption remains prevalent in the judiciary, and the European Union has recently suspended funding for apparent fraud and misuse of funds.

A democratic system does not guarantee a society that is free from corruption. Petty corruption tends to be far less prevalent in strong democratic systems with more open systems of governance, but one can still find plenty of examples of political corruption at high levels or of money influencing politics. These include scandals involving questionable party financing, the selling of political influence to the biggest donors, and politicians using connections to line their own pockets. Campaign finance reform continues to be a subject of much debate in the United States, where the electorate remains concerned about moneyed special interests having undue influence over legislators.

Another example from the West was the high-level corruption of political parties in Italy, which led to a number of scandals in the 1990s. The political party in power made sure that its members dominated government positions. Its members in key positions awarded government contracts to businesses for a price of a bribe, then, gave the money to the party. Among other illicit activities, funds for large infrastructure projects were funneled into party coffers.16 Transparency International’s Corruption Index 2008 shows that many of the least corrupt countries are democracies. However, countries with less democratic, more authoritarian systems of governance, such as Singapore, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain are also some of the least corrupt.

Also, democracy is not a panacea for problems related to corruption and conflict. A rule by majority can neglect the needs and desires of minorities, marginalize them, and thus contribute to the rise of separatist movements and even violent rebellions, even with many political parties. And, it takes a long time to establish a solid democracy in societies transitioning from conflict to peace.

What Structures Help Prevent Corruption?

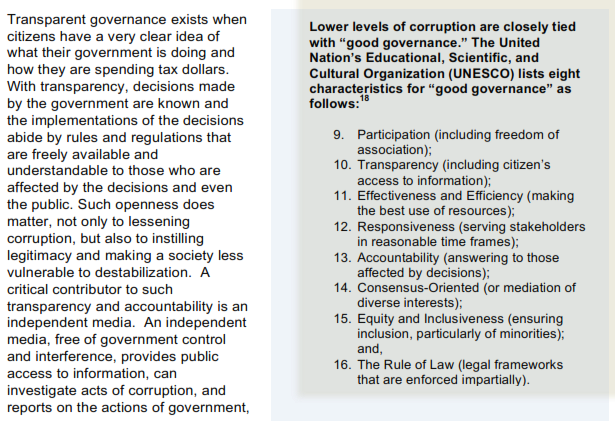

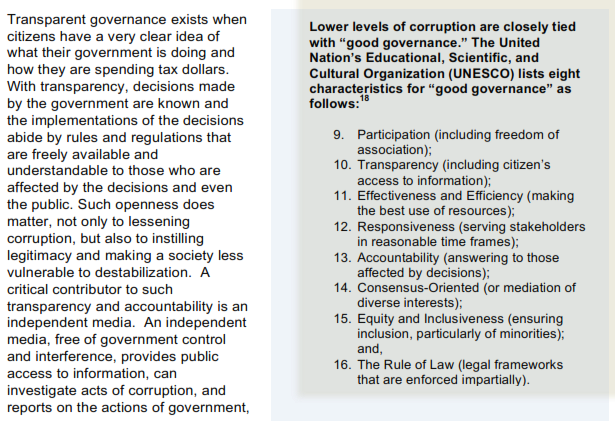

“Good governance” principles can make it more difficult for corruption to take root. Of many requirements of good governance, some key components are participation, accountability, transparency, and rule of law. (See box in Good Governance.) It is the combination of the principles that can help stem corruption and build a stable society. And, in a system where rule of law prevails, citizens have an equal standing under the law regardless of their political affiliation, social status, economic power, or ethnic background. Public participation greatly helps mitigate conflict because there are legitimate public forums and mechanisms for peaceful debate. Public participation in politics (through elections, political parties and civil society organizations) can provide a check on the government and keep political authorities accountable. Such accountability is enhanced by the rule of law, which encompasses the processes, norms, and structures that hold the population and public officials legally responsible for their actions and impose sanctions if they violate the law.

Good Governance

More open and representative governing systems that allow for a high level of civic participation typically have more vibrant civil society organizations that can publicly reveal the abuses of corrupt officials and put their political futures at risk. Civil society describes groups of civilians that work voluntarily (vs. by the mandate of the state) and the organizations that are thus formed to advance their own or others’ well-being. It can include civic, educational, trade, labor, charitable, media, religious, recreational, cultural, and advocacy groups. A strong civil society can protect individuals and groups against intrusive government and influence government behavior, protecting the marginalized and furthering the interest of the governed.

Elections provide an important method of public participation in governance and give legitimacy to a government chosen by the people. Free and fair elections also have the effect of holding leaders accountable because, if they misuse their office, they can be voted out of it by citizens during the next election cycle. Given a choice, citizens are not likely to vote for incumbents whom they believe are corrupt or ignore corruption, and can vote candidates into office who are running on anti-corruption platforms.

Public accountability remains one of the most important mechanisms to control

corruption. Can officials (elected or otherwise) be exposed to public scrutiny and

criticism for not meeting standards and for wrongdoing? Or, perhaps more importantly,

can they lose their jobs or be put in jail? Susan Rose-Ackerman notes that “Limits on the power of politicians and political institutions combined with independent monitoring and enforcement can be potent anti-corruption strategies.”17

thus helping to ensure greater transparency and accountability.

Rule of Law

Most policymakers would agree that having “rule of law” tradition is one of the most effective ways to keep corruption in check. A state can operate under many different forms of governance, from autocracy to democracy, and remain stable and free of internal violence, but having widespread respect for rule of law in place ensures that all persons and institutions, public and private, including the state itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly announced, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and consistent with international human rights norms and standards. While no country is

immune from corruption, it tends to be more common in societies where there is not a strong commitment to the rule of law.

In a system where the rule of law has broken down, there is little transparency in government operations and public officials have a lot of discretion in the way that they carry out their duties. It is more likely that government funds will be used for personal benefit, that services will be disrupted, and that citizens will have few avenues of recourse to lodge complaints, or receive justice. In such circumstances, citizens may revolt (violently or non-violently), or perhaps protest in other ways, like evading paying taxes—believing that there in no point in doing so when they expect the money to go into the pockets of corrupt officials and not to the services that they use (like roads, hospitals, or schools). Tax evasion remains a big problem in countries like Russia, where economic uncertainty after the fall of the Soviet Union led to poverty, corruption, new waves of crime, and a growing distrust of authorities. Tax evasion is also prevalent where there is no rule of law because too often tax collection is either not enforced impartially or equitably. And, in some societies, instead of paying taxes (a legitimate contribution to support government services), citizens will save their money for bribes since that may be a more effective means of ensuring they receive services.

Where Is Progress Being Made Globally?

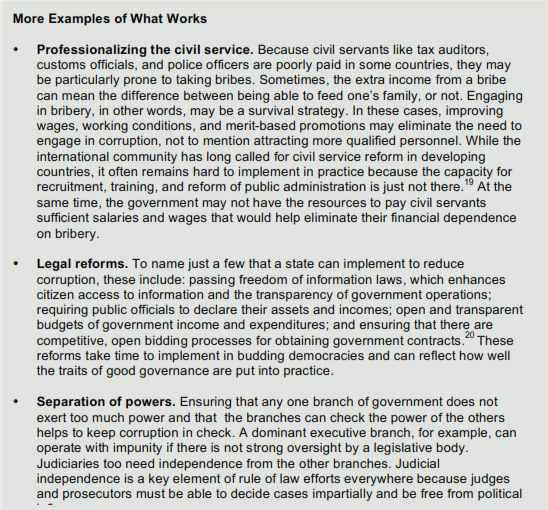

Many governments around the world have anti-corruption laws on their books, but if they are not enforced, they may have little impact on reducing corruption. Those committing corrupt acts must ultimately be brought to justice. Governments need to send “a signal that the existing culture of impunity will no longer be tolerated,” says the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), whose Threshold Programs aim to tackle corruption in several countries.21 They point to work in the Philippines, where the government is focused on stepping up enforcement efforts and significantly increasing the corruption conviction rate. Tanzania too, notes MCC, is “reducing the backlog of pending corruption cases to ensure that violators who are caught are brought to trial in a timely manner.”

Anti-corruption measures can be punitive in nature, focusing on legal prosecution for crimes committed, or preventive, focusing on making sure that corruption does not happen in the first place through practices like implementing accounting controls and regular audits. Both of these are covered in the United Nations Convention against Corruption, which was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2003, entered into force in 2005, and currently has 140 signatories. This legally binding instrument requires states to develop independent anti-corruption bodies and transparent procurement systems, criminalizes certain offenses, and puts measures in place for states to cooperate more closely with each other on fighting corruption. There are also a variety of similar agreements at regional and global levels, including the African Union, the Organization of American States and the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development)—for example, making it illegal to bribe foreign public officials. Such agreements have contributed to a stronger international consensus about corruption and its costs and have increased the number of cases brought before judicial bodies. Critics, however, point out that effective monitoring processes are still lacking and that it remains difficult to track payments that are made through intermediaries (rather than directly). Too often, these conventions are not self-enforcing and require enforcement by national authorities. Common standards have been agreed to by the international community, but greater enforcement at the national level, more compliance by private companies, and greater public education and pressure from civil society groups, are needed.

Anti-corruption campaigns are likely to be more successful when they are backed by strong leadership at the highest levels of government. Although news reports on corrupt heads of state in Africa are common, there are also examples of African leaders who have made fighting corruption central to their administrations. Seretse Khama, the president of Botswana from 1966 to1980, did not tolerate a culture of corruption in his government and put strong measures in place against it. Officials who misappropriated funds were prosecuted. With state resources used to build the country’s infrastructure, Botswana underwent rapid economic and social progress during his term in office. The current president of the Republic of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, has also exercised “leadership from the top” in fighting corruption. He has professionalized the police force, required all public officials to post earnings statements, and has imprisoned officials caught pilfering public funds.22 There is a long history of corruption in Liberia, which will take time and effort to address. However, President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, who took office in early 2006, has launched various efforts to tackle corruption, including protections for those providing information on stolen assets, improving financial management and accountability, and prompt payments for government employees.

Liberia also has an Anti-Corruption Commission, tasked to investigate potential acts of corruption and carry out a public education campaign to highlight its work and shame corrupt officials, but like many other similar institutions in developing countries, it does not have enough staff and resources to be truly effective. While such commissions have had strong enforcement powers and worked very well in wealthier countries like Singapore and Hong Kong, they have not been as successful elsewhere. One of the major critiques of such commissions is that they are encouraged by international donors, but often do not have political support—or capacity—locally.

In addition, there is often resistance among countries in the developing world because they equate anti-corruption campaigns or conditions placed on international donations as attempts by the developed world to “govern other countries like a colonial power,” in the words of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. He and other developing world leaders and economists often charge the donor countries as using anti-corruption requirements as a way to dictate to poorer countries economic, political, and foreign policy decisions.

More successful initiatives have been ones like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Now a global activity supported by companies, countries, civil society, and international organizations, EITI has improved transparency and accountability in the extractive sector, e.g., oil, gas, and minerals. It does this by verifying and publishing both company payments and government revenues from these resources. By making these processes more transparent, the ultimate goal is to see that these natural resources become a means of development rather than a cause of poverty and conflict. EITI has become the global standard in this particular industry, with many hoping to apply the model of international cooperation to other sectors.