Chapter 7. Introduction to a ten pesos Mexican banknote

One of the interesting documents available on the Our Americas Archive Partnership site is a ten pesos Mexican banknote. This banknote was put into circulation in May 1823, after the fall of Agustin de Iturbide’s First Mexican Empire. It is important to contextualize this document within Mexican history in order to understand its importance.

Independence, Empire, and the Republic of Mexico

Mexico’s War of Independence from Spain began on September 16, 1810 and ended in 1821. In 1821, after the proclamation of the Plan of Iguala (in February) and the Treaty of Cordoba (in August of the same year), which recognized Mexican independence from Spain, Agustin de Iturbide was proclaimed President of the Regency. Not long afterward, in May 1822, Iturbide crowned himself First Emperor of Mexico. Iturbide abdicated his throne in March 1823, after the signing of Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana’s Plan of Casa Mata, which sought to reinstate the Mexican Congress, declare the empire null, and no longer recognize Iturbide as the emperor.

Stephen F. Austin and the colonization of Texas

Before the conclusion of Mexico’s War of Independence, Moses Austin received a land grant for the colonization of Texas. His son, Stephen F. Austin, began to fulfill these plans after his father’s death in December 1821, but was impeded by Iturbide’s provisional government, established after independence. This new government refused to recognize this grant; they preferred to pass an immigration law in its place. As a result, Austin travelled to Mexico City to ask Iturbide and his rump congress to approve his land grant. After Iturbide’s abdication and the fall of the First Mexican Empire in 1823, Austin had to ask the Mexican Congress once again to recognize the original land grant for colonization (Barker).

Brief history of Mexican currency

The history of currency in Mexican is situated within the nation’s turbulent history. During the War of Independence New Spain’s mines– which supplied the gold, silver, and copper for minting coins– were abandoned. Due to the poor economic situation and the abandonment of the mines, Mexico turned to paper currency (or banknotes) in 1822, during Emperor Iturbide’s reign. The general public, however, was used to using coins and, consequently, rejected these banknotes (“Conoce la historia”).

After the fall of the Empire in 1823, the new Mexican Republic retired the imperial banknote from circulation as part of their efforts to reestablish the public’s trust in the government’s financial management. The poor economic situation, however, did not improve and the government decided to print paper currency or banknotes, once again (“Conoce la historia”).

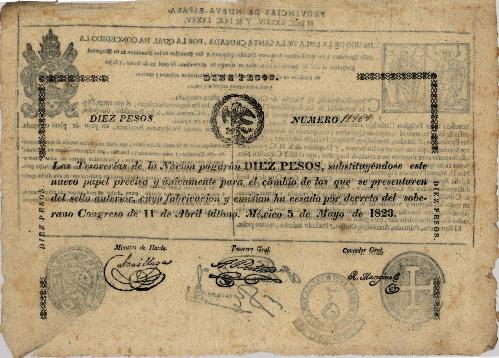

This ten pesos banknote is one of the national banknotes issued in 1823 under the new Mexican Republic. It was printed with the national seal of Mexico, the eagle on a cactus, and says the following:

"The National Treasury will pay TEN PESOS, precisely and exclusively substituting this

new paper in exchange for those that bear the previous seal, whose fabrication and

exchange has ceased in accordance with a decree issued by the sovereign Congress on

April 11 of last year. Mexico May 5, 1823." (Ten pesos).

To avoid the public’s rejection, as had previously occurred during the Empire, the government decided to print this new paper currency on the backs of Catholic bulls. The government made this decision based on the idea that the Mexican people’s religiosity would encourage them to use the banknotes. Yet, the banknotes were rejected once again (“Conoce la historia”). The possibility of a paper shortage during the poor economic situation that Mexico found itself in after the War of Independence and the fall of the First Empire could have also influenced the decision to recycle another document or old paper.

Paper currency was not accepted by the Mexican public until 1864, during the Second Mexican Empire under Emperor Maximilian, when the Bank of London, Mexico, and South America, a private bank, was put in charge of issuing currency.

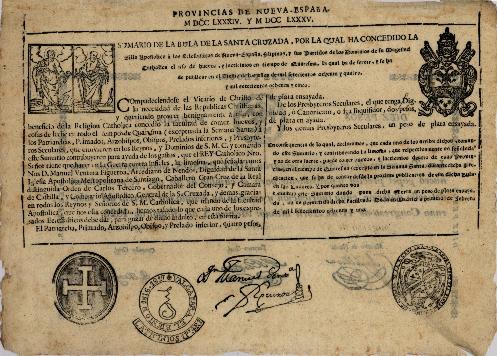

Verso: Catholic Bull

On the other side of this banknote is an eighteenth century Bull of the Holy Crusades. A Bull of the Holy Crusades is a bull that granted indulgences in exchange for a monetary contribution. This contribution was used to finance wars against infidels.

This particular eighteenth century bull concedes “the use of eggs and dairy during Lent (with the exception of Holy Week).” These indulgences were conceded to “Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops, Bishops, lesser Prelates, and Secular Presbyterians” (Ten pesos). These ecclesiastics paid different amounts, according to their position. The archbishop, for example, had to pay four pesos of assayed silver, while the secular presbyterians only had to pay one peso of assayed silver. The use of the phrase “assayed silver” in this bull reminds us that coins made of silver and not paper currency were used during this time period.

Conclusion

The juxtaposition of these two texts, the ten pesos banknote and the Catholic bull, presents us with an interesting piece of history that connects two distinct moments in Mexican history. The Catholic bull belongs to the period of Spanish colonization, during which Mexico was part of New Spain. The Catholic Church was part of the colonization efforts that were manifested through the founding of missions that facilitated the imposition of the Spanish empire. As a result, this bull signifies Mexico’s Spanish Colonial past, while the ten pesos banknote represents the new republican steps taken by an independent nation.

We add to this history the presence of newly-arrived colonists to the Mexican province of Texas, who could have also used or rejected this banknote. Texas’ early history (and the beginnings of Austin’s colony) was closely tied to Mexico’s political history. As we saw, Austin’s land grant had to be reevaluated every time the Mexican government changed.

In conclusion, this short document presents a long trajectory of Mexican history and deals with several themes, including: imperialism, independence, nationalism, colonization, inter-American relations, religion, war, and economy.

Bibliography

Barker, Eugene C. "Austin, Stephen Fuller." Handbook of Texas Online. (Texas State Historical Association) http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fau14

"Conoce la historia del billete mexicano".Banco de México. 17 de septiempre 2010. http://www.85aniversariobanxico.com/2010/09/conoce-la-historia-del-billete-mexicano/

Ten pesos: [Texas Currency]. Trans. Lorena Gauthereau-Bryson, Tesoreria de la Nacion, 1823. http://hdl.handle.net/1911/27466