Rare Letters of Jefferson Davis

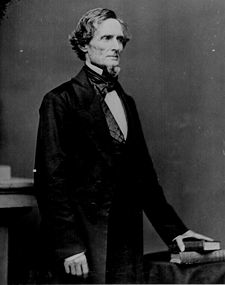

Jefferson Davis (1808-1889) led a varied career, indicative of the controversial place he occupies within United States history. He spent his early adulthood in the U.S. military, then years later drummed up a volunteer force to fight in the Mexican-American War. After the war, he settled on a life in politics. In his first attempt, he was elected to the U.S. congress as a senator from Mississippi. He served for a brief period as the Secretary of War under Franklin Pierce; when his term ended in 1857, he returned to his seat in the Senate. In the years leading up to the Civil War, he actually opposed secession and fought hard for a compromise to ensure the integrity of the Union. When he learned of Mississippi’s decision to secede, however, Davis returned home and was promptly elected to a six-year term as the first (and only) President of the Confederate States of America. After the Confederacy’s defeat, he was banned from ever holding political office, yet he was lionized in the South for the remainder of his life. While the nation at large officially branded him a traitor, an entire region continued to deem him a hero. Today, many schools throughout the South are named in his honor. The ambiguity surrounding Davis’s legacy ties into the social and political fissures within the U.S. that have formed historically along the lines of race and region.

The ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership – a collection of primary documents dedicated to the study of inter-American cultural and historical relations – possesses a set of rare and unpublished letters authored by Davis. Held at Rice University’s Woodson Research Center, which also contains other materials by and about Davis (including a clothing order on his behalf), these letters can be broken down into three chronological periods: a pre-Civil War era that sees Davis as a functionary of the U.S. government (four letters), Davis’s presidency during the Civil War (two letters), and a brief period at the very end of Davis’s life (two letters). These documents form a remarkable, if microscopic, arch to his life and career and will be of great value to the scholar and student alike interested in Davis’s biography. This module will offer a brief overview of each timeframe as well as some of the letters contained therein. For a more detailed examination of Davis and his historical context, see William Davis’s Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour and George Rable’s The Confederate Republic: A Revolution against Politics. One can find the majority of his published writings in The Papers of Jefferson Davis, edited by Haskell Monroe, James McIntosh, and Lynda Crist.

The earliest letter in the archive dates from December 10, 1846. It is written from Davis to his wife, Varina “Winnie” Davis, during his time spent fighting in the Mexican-American War. This document offers dual insights into both his early military career and his personal/family life. He describes for his wife the movements of Santa Anna and the Mexican Army, then tells her about another military wife in New Orleans to whom he would like to introduce her. The remaining letters in the pre-Civil War timeframe come from the 1850s, while Davis was serving as an elected official in the federal government. All of them find Davis either recommending or agreeing to recommend someone for a post in the U.S. military. Here we are left to conclude that his opinion was a valued one, especially on military matters, an assumption which is borne out, of course, by his aforementioned position within the War Department under President Pierce.

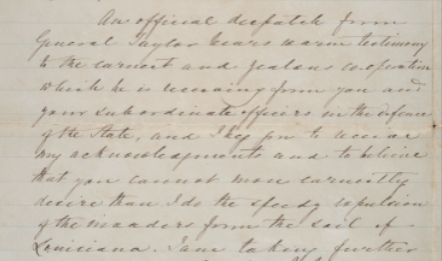

One of the Civil War-era letters is part of a correspondence between Davis and General Joseph Johnston, and the other contains a set of updates from Davis to Thomas Moore, then governor of Louisiana. Written in response to Johnston's March 3, 1862 letter, Davis's brief note addressed the general’s concerns over the inadequacy of the South’s roadways and resources for the logistics of warfare. Davis cannot offer much reassurance, and one can sense in this exchange the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of the Confederacy’s ambitions. In his letter to Moore dated September 29, 1862, Davis is clearly trying to assuage the governor’s anxieties about the vulnerabilities of his state, in particular, to the invading Union forces. Davis writes, “An official dispatch from General Taylor bears warm testimony to the earnest and zealous co-operation which he is receiving from you and your subordinate officers in the defence of the State, and I beg your to receive my acknowledgments and to believe that you cannot more earnestly desire than I do the speedy repulsion of the invaders from the soil of Louisiana” (see Figure 2). The pressure upon Davis is palpable in this document, as he struggles to strengthen the resolve and maintain the loyalty of those under his leadership.

The final two letters, one from 1887 and the other from 1888, were both written at Davis’s Beauvoir estate in Biloxi, Mississippi, where he spent his final years. Addressed to Dr. W. H. Sanders, the first letter is a short one simply declining an invitation due to illness. The second letter, to Martin W. Phillips, is a much longer one that finds Davis in a reflective mood. He states early in the text, “Many sad changes have occurred within that time but the saddest of all to me is the tendency in our own people to “harmonize” away the principles for which they gave property + life hoping thereby to preserve what was to them of greater value” (1). Here Davis is lamenting what many supporters of the South after the Civil War termed “The Lost Cause.” It is difficult from this brief snippet to determine if at the end of his life Davis remained invested in the specific principles for which the Confederacy fought, or if he was attached in a more romanticized fashion to the idea of the Confederacy itself. Regardless, this relatively lengthy letter (four pages) provides a fascinating peek into the private thoughts of such a major historical figure during his waning days.

These unpublished letters, accessible physically and digitally through the Americas Archive, offer exciting pedagogical opportunities for a variety of classroom settings. They would of course be valuable within any course on nineteenth-century U.S. history, or one more specifically focused on the U.S. South. Biographical approaches to Davis either individually or in concordance with other major U.S. political figures would likewise benefit from these documents. Yet another use for these letters – perhaps a less obvious one – would be in relation to the field of U.S. literary studies. The writings of other political figures, such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, have found their way into the literature classroom (and, in fact, Davis authored two books during his later years, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government and A Short History of the Confederate States of America). As the category of literature continues to shift to include different figure and various types of texts (letters, diaries, journals, etc.), archives become invaluable tools in providing new material to process, study, and interpret. Archives such as the Americas Archive and letters such as these by Jefferson Davis demand that we question what precisely constitutes “literature” and who exactly counts as the producers of “literature.”

Bibliography

Davis, Jefferson. The Papers of Jefferson Davis. Ed. Lynda L. Crist, James T. McIntosh, and Haskell M. Monroe. Revised edition. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2003.

Davis, Jefferson. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1881.

Davis, Jefferson. A Short History of the Confederate States of America. New York: Belford Co., 1890.

Davis, William. Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1996.

Rable, George C. The Confederate Republic: A Revolution against Politics. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1994.